Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

The 27-Item Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire: A New Brief Measure Including Treatment Burden and Work Life

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Treatment- and work-related aspects have been neglected in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures in multiple sclerosis (MS). We aimed to develop a brief instrument covering all important impairment-, activity-, participation-, and treatment-related aspects for use in research and practice.

METHODS

The 27-item Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (MS-QLQ27) was developed using open item collection, a multidisciplinary expert panel, and cognitive pretesting. It was evaluated for reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness in 100 patients presenting with relapse (84 at follow-up ~14 days later). Construct validity was analyzed by correlating the MS-QLQ27 with the disease-specific Hamburg Quality of Life Questionnaire in MS (HAQUAMS) and generic HRQOL instruments. The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) was used to analyze known-groups validity. Responsiveness was determined as the correlation of changes in MS-QLQ27 scores with changes in validation criteria.

RESULTS

Internal consistency was high (Cronbach α = 0.94 at baseline and 0.93 at follow-up). Convergent validity was supported by direction and magnitude of associations with disease-specific and generic instruments. Correlations with change in convergent criteria were strong, indicating responsiveness. The HAQUAMS showed the strongest associations with the MS-QLQ27. The MS-QLQ27 showed the highest effect size compared with other patient-reported outcomes and the EDSS. It successfully distinguished between levels of disease severity.

CONCLUSIONS

These results indicate that the MS-QLQ27 is a reliable, valid, and highly responsive instrument for assessing HRQOL during relapse evolution in MS. Its advantages are that it is brief yet comprehensive, covering work- and treatment-related aspects not addressed in previous measures.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is considered a key outcome for persons with multiple sclerosis (MS) and is increasingly being assessed in both clinical practice and trials.1–3 Measures of HRQOL can contribute to clinical trials by more fully assessing therapeutic efficacy4 and by being more comprehensive than scales that assess only the degree of neurologic deficit. Whereas in clinical trials accuracy, validity, and responsiveness of instruments are most relevant, barriers to the adoption of HRQOL in clinical practice arise mainly from choosing and interpreting HRQOL scores.2 Time and resources are limited in routine medical practice, creating a need for tools that are simple, short, and easy to interpret.

In patients with MS, HRQOL is associated with physical and mental factors such as depression and anxiety symptoms, fatigue, and cognitive functioning.5,6 Social functioning, from sexual disturbances to free-time activities and work-related issues, affects HRQOL7 and is considered to be more difficult to manage and, therefore, is underrecognized.8 Work-related problems or even unemployment due to MS are common in this population even when physical disability is low.9 Finally, treatment for relapses10–12 as well as long-term immunotherapies13,14 can pose a significant burden on people with MS.

Despite the number of disease-specific instruments that have been developed in the past 20 years and the many phase 2 and 3 trials, there is still no HRQOL instrument generally accepted and adapted widely in routine care. Neither has there been established an agreed-on tool to monitor the impact of MS relapses from a patient perspective. Some of the HRQOL instruments put a focus on comprehensiveness and are, therefore, rather long and time-consuming, such as the Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis (59 items)15 or the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory (138 items).16 Other instruments are briefer but do not include important aspects of HRQOL, such as work life problems. Examples are the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life questionnaire,17 the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale,18 and the Hamburg Quality of Life Questionnaire in Multiple Sclerosis (HAQUAMS).19 To our knowledge, the aspect of treatment burden is lacking in all available instruments. Regarding psychometrics, only some have been tested for responsiveness to change (eg, the Patient-Reported Indices for Multiple Sclerosis,20 the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life questionnaire,16 and the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54).21

To capture the manifold factors of HRQOL impairment described previously herein, a comprehensive standardized instrument is needed. At the same time, to be suitable for use in both research and clinical practice, the instrument should be as brief as possible and should be able to depict clinical change. The instrument should be applicable to monitor relapse and long-term treatment. Its content should be rigorously based on patient input to capture the most patient-relevant outcomes.2,22 To our knowledge, an instrument with this combination of characteristics is currently lacking. Therefore, we aimed to fill this gap with the newly developed 27-item Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (MS-QLQ27), presented in this report.

METHODS

Item Generation

The MS-QLQ27 was developed in a 4-step procedure: (1) open item collection, (2) multidisciplinary expert panel, (3) cognitive pretesting, and (4) longitudinal validation study.

Open Item Collection

Data on patient-relevant impairments were collected in an open survey of 59 patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) recruited at the MS outpatient clinic of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) between May 2013 and July 2013. Patients were in different disease stages, that is, either in relapse or in remission. In a questionnaire, patients were asked to describe, in their own words, impairments due to their disease (RRMS) in general, as well as during a relapse, and impairments in different areas of their lives.

Multidisciplinary Expert Panel

Items for the MS-QLQ27 were defined by a multidisciplinary expert panel that included patients, methodologists, neurologists, and study nurses. Inclusion of the patient perspective and preferences at this stage was essential in selecting and wording the final items. To add clinical and methodological knowledge, experts in MS care and psychometrics were involved in the discussion.

The frequency with which impairments had been mentioned in the item collection survey was used as the basis of the decision process. The expert panel categorized and discussed these impairments regarding their suitability to capture general and condition-specific burden. Items were included if they were both frequently mentioned and clinically relevant; items were excluded if they were redundant, ambiguous, and/or infrequently mentioned in the open item collection. Finally, 27 items were incorporated into the MS-QLQ27 pilot version.

Cognitive Pretesting

The MS-QLQ27 was subsequently tested for comprehensiveness and practicality in cognitive interviews with 10 patients with RRMS. Interviews were conducted at the center where recruitment for the open item data collection took place. Debriefing questions were used to identify items or words that were not understood or that were interpreted inconsistently by respondents and to obtain suggestions for revising questions. Patients also assessed the structure and layout of the questionnaire.

Longitudinal Validation Study

One hundred patients with RRMS were enrolled consecutively in a prospective, uncontrolled cohort study at the MS outpatient clinic of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) (n = 65) and at an outpatient neurologic practice in Hamburg, Germany (n = 35), between November 2014 and January 2016. To validate and test the instrument under clinical conditions, patients with RRMS with confirmed exacerbation who were due to receive treatment in the following 24 hours were included in the study. A relapse is a “patient-reported, or objectively observed, event typical of an acute inflammatory demyelinating event in the central nervous system, current or historical, with a duration of at least 24 hours.”23 We excluded patients with a major impairment of visual, hand, or cognitive function who were unable to complete the questionnaire on their own.

Case report forms were completed by patients and their neurologists before relapse treatment (baseline) and approximately 14 days later (follow-up). These forms included demographic and clinical data as well as disease-specific and generic HRQOL instruments as convergent validation parameters for MS-QLQ27 instrument evaluation.

For disease-specific HRQOL, we used the validated HAQUAMS,19 version 10.0. Its total score is based on 6 subscales: fatigue, thinking, upper limb mobility, lower limb mobility, mood, and communication. Generic HRQOL was assessed with the widely used preference-based questionnaire EQ-5D-3L.24 This tool records 3 levels of severity in 5 dimensions (morbidity, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) and yields a single index value from 0 (lowest) to 1 (highest).25 The EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ VAS) recorded each respondent’s self-rated health on a vertical visual analogue scale with end points that were labeled 100 (best imaginable health state) and 0 (worst imaginable health state).

Methods to Test MS-QLQ27 Validity

Distributional properties were explored using descriptive statistics: mean, standard deviation, percentage of patients scoring the minimum and maximum possible scores (floor and ceiling effects), and missing values. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach α and corrected item scale correlations.

Convergent validity was assessed by means of cross-sectional associations (Pearson correlation) among the HAQUAMS (subscales and composite score), EQ-5D-3L, and EQ VAS.

In accordance with Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments criteria,26 responsiveness was defined as the correlation of changes in MS-QLQ27 with changes in convergent criteria, which was tested for by determining partial correlations of posttreatment values while controlling for pretreatment values.

We hypothesized stronger associations with the HAQUAMS, which is disease-specific, than with the EQ-5D-3L and EQ VAS, which are generic.

Known-groups validity was assessed by examining MS-QLQ27 total score by baseline Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) through 1-way analysis of variance with Scheffé post hoc tests. The EDSS score groups were defined as follows: 0 to 2.5, minor impairment; 3.0 to 4.5, moderate impairment; and 5.0 or greater, severe impairment.27 For known-groups validity analysis, we also anticipated differences between patients with short (≤5 years) and long (>20 years) disease duration.

Computation of MS-QLQ27 Global Score

The global score was computed as the arithmetic mean of all valid items (from 1 = not at all impaired to 5 = extremely impaired). If more than 75% of items were invalid or missing, no global score was computed. Within the MS-QLQ27, we used a filter question on patient employment status (“Do you work or are you in training or studying?”). If a patient ticked “No, due to multiple sclerosis” or “No, for other reasons,” the global score was computed without items 26 and 27, which relate to work life impairment. In this event, items 26 and 27 were not counted as missing.

Factor and Statistical Analyses

To identify underlying dimensions of the MS-QLQ27, based on which potential subscales could be determined, a factor analysis with varimax rotation was performed over the 27 items, and factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1 were extracted. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp).

Ethics

The validation study was approved by the ethical review committee of the Medical Association of Hamburg and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent before the start of the study.

RESULTS

Instrument Development

Fifty-nine patients with RRMS (37 women [63%]) with a mean (SD) age of 37.3 (9.9) years completed the questionnaire during open item collection. The item pool contained 398 entries relating to impairments. Informed by the expert panel and cognitive pretesting, the final instrument, which was named MS-QLQ27, contained 27 physical, mental, and treatment-specific impairments as well as items relating to leisure, social, and work life issues. As a result of the pretesting, modifications in wording and use of additional examples in 3 items were made to ensure content comprehension. For example, the term language difficulties was made more specific and became difficulty finding words or speaking, and the item difficulty doing everyday things was extended by (eg, housework).

Validation Study

Patients

The validation study sample consisted of 100 patients at baseline, of which 84 also participated at follow-up (TABLE S1, which is published in the online version of this article at IJMSC.org). Out of the 84 patients at follow-up, 61 patients (73%) self-reported as female, 20 self-reported as male, and 3 did not specify their sex. Mean (SD) age was 38.3 (18.9) years and disease duration was 8.3 (7.6) years. The EDSS scores ranged from 0.0 to 6.5, with moderate mean (SD) EDSS disability of 2.7 (1.6).

There were only small differences in demographic and clinical characteristics among participants between baseline and follow-up. The overall dropout rate at follow-up was 16%. Patients were mainly lost to follow-up due to a failure to present at a scheduled appointment (follow-up). The dropout analysis showed that the demographic and disease characteristics of dropouts did not differ significantly from those of the remainder of the sample. Descriptively, patients who dropped out were older, had a longer disease duration, and showed higher severity of MS.

HRQOL and Treatment Characteristics

During mean (SD) follow-up of 17 (4.4) days, patients were treated with cortisone pulse therapy for 3 to 5 days: 84% were treated with high-dose oral corticosteroids (500–1000 mg/d) and 16% with ultrahigh dose oral corticosteroids (>1500 mg/d).

The mean (SD) MS-QLQ27 global score at baseline was 2.31 (0.72) (range, 1–5); this score decreased significantly to 1.95 (0.72) at follow-up (TABLE S2). With an effect size of −0.5, this improvement depicted by the MS-QLQ27 was considerably greater than that in the other HRQOL instruments showing effect sizes around 0.3.

Distributional Characteristics of MS-QLQ27

Difficulties with walking, paresthesia (eg, numbness and tingling), and fatigue followed by physical weakness were the most pronounced impairments at baseline (TABLE S3). For items relating to social life, such as “lack of understanding of others” or “limited social interaction,” lower mean values were found and fewer patients reported the highest possible value, indicating less pronounced impairment.

The number of missing values per MS-QLQ27 item at baseline was between 6.0% and 13.1% (average, 7.2%). At follow-up, we found a lower number of missing items, ranging from 1.3% to 10.3% (mean, 3.5%). Most missing values were found for the following items: at baseline, for item 25 “side effects of the treatment” (13.1%) and item 20 “limited sex life” (10.7%), and at follow-up, for item 26 “not able to work” (10.3%). Sixty-two percent of the patients were working at baseline according to the MS-QLQ27 question on occupational status, 18% answered “No, due to multiple sclerosis,” 10% answered “No, for other reasons,” and 10% were missing.

Internal Consistency

Cronbach α coefficients indicated high reliability at both measurement points, with values of 0.93 (baseline) and 0.94 (follow-up). The corrected item scale correlation ranged from r = 0.31 to 0.76 at baseline, with a large proportion of items (23 of 27) showing values greater than or equal to 0.5. Item 4 (“problems with eyesight”) correlated very weakly with the overall scale (baseline r = 0.05, follow-up r = −0.03).

Factor Analysis

The factor analysis with varimax rotation revealed 7 factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1, explaining 72.3% of item variance. However, multiple items loaded highly and to a similar extent on more than 1 factor, which means that they could not be assigned to specific dimensions. Thus, items could not reasonably be assigned to different subscales so that only the global score was determined.

Convergent Validity and Responsiveness

As anticipated, strong correlations of the MS-QLQ27 score were found with the HAQUAMS total score, both cross-sectionally (r = 0.84, r = 0.86; P < .001) and longitudinally (r = 0.68; P < .001) (FIGURE S1). The MS-QLQ27 correlated to a lesser extent but still highly significantly with the generic EQ-5D-3L at both measuring times (r = −0.63 and r = −0.73, respectively; P < .001) and with changes in EQ-5D-3L (r = −0.56; P < .001). The association between the MS-QLQ27 and EQ VAS was moderate, both cross-sectionally (r = −0.55, r = −0.64; P < .001) and longitudinally (r = −0.49; P < .001).

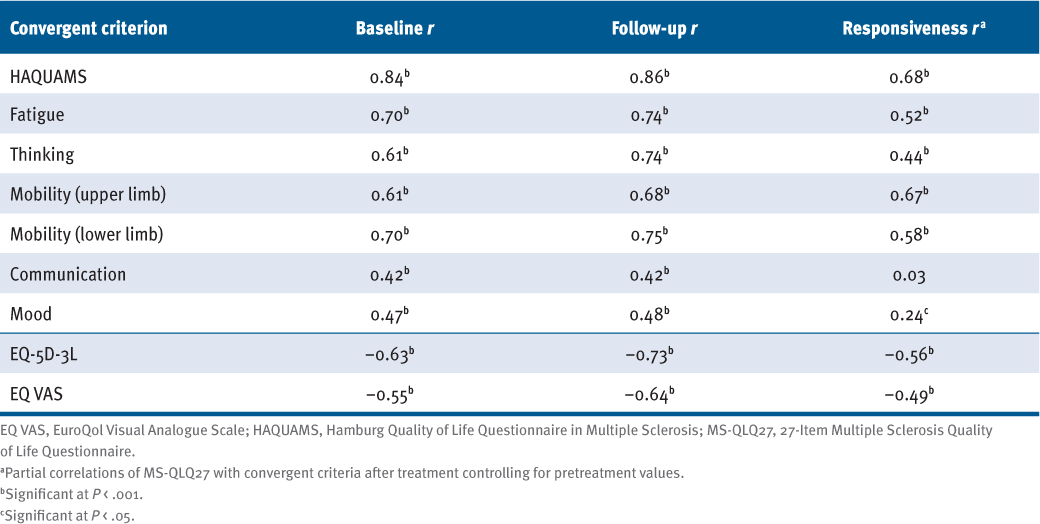

Change in the MS-QLQ27 score was moderately associated with change in the HAQUAMS subscales “fatigue,” “thinking,” “mobility upper limb,” and “mobility lower limb” (r = 0.44–0.67; P < .001) and to a lesser extent with the subscale “mood” (r = 0.24; P < .05). The “communication” subdomain was not correlated with the MS-QLQ27 longitudinally (TABLE 1).

Hypothesis Testing: Convergent Validity and Responsiveness of MS-QLQ27

Known-Groups Validity

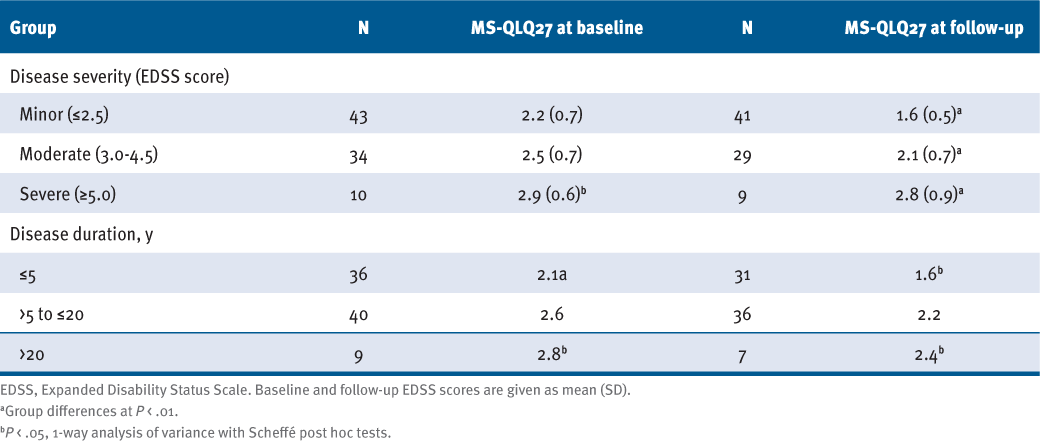

Results for known-groups validity indicate that the MS-QLQ27 successfully distinguished between groups of low, moderate, and high disease severity as measured with the EDSS: As expected, individuals with greater disability had significantly higher MS-QLQ27 scores. The post hoc test was significant at baseline for the comparison between patients with low and severe impairment (P = .012), and likewise at follow-up among all 3 groups.

Individuals with longer disease duration had significantly higher MS-QLQ27 scores (TABLE 2), as anticipated. At baseline and follow-up, differences in MS-QLQ27 scores were significant between patients with short (≤5 years) and moderate (>5–20 years) disease duration (P = .001 and P = .014) and between those with short and long (>20 years) disease duration (P =.43 and P = .011).

Association of 27-Item Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (MS-QLQ27) With Disease Severity and Disease Duration Subgroups

DISCUSSION

With the MS-QLQ27, we aimed to fill a gap in the range of MS-specific HRQOL instruments currently available and to develop a valid and responsive questionnaire that is brief, comprehensive (encompassing aspects such as work life and treatment burden), easy to complete (by using a single response scale for all items), and suitable for use in clinical practice and research.

There is still no agreed-on instrument to document the evolution of relapses. Commonly used severity and disability measures have been found to insufficiently capture the impacts of relapses that both patients and clinicians consider relevant.28 Only a limited percentage of relapses show EDSS-relevant alterations, and many cohort studies on relapse treatments have focused on only global clinical impression. New approaches to measure patients’ views on treatment benefit should fill this gap.29 The MS-QLQ27 offers another sensitive option that might be applicable in relapse treatment approaches: being aware that high-dose corticosteroids are of limited effectiveness and associated with substantial adverse effects.12

After identification of impairments in general and during relapse in an open item collection process and discussion of the results by an expert panel that included patients, the pilot version of the MS-QLQ27 was tested using a cognitive pretest to ensure comprehensibility and practicability. The development process included patients during all steps and is, therefore, expected to ensure content validity. In the final version of the instrument, patients are asked to rate to what extent the 27 listed impairments have affected their lives in the past 7 days.

The distributional characteristics at baseline indicated a relatively high rate of missing values in MS-QLQ27 items, notably concerning treatment adverse effects, limitations in sexuality, and absenteeism/not being able to have a job. Missing values for treatment adverse effect items were probably high because some patients did not receive any treatment at baseline. At follow-up, the number of missing items was lower, with a satisfactory mean value of 3.5%.

The relatively high proportion of “not at all” impaired responses at baseline can be attributed to the rather low disease severity in the sample (mean [SD] EDSS score, 2.7 [1.61]), which decreased further by follow-up due to relapse treatment. Accordingly, both the MS-QLQ27 global score and other HRQOL measures decreased considerably by follow-up. This effect was found to be strongest in the MS-QLQ27, which underlines its responsiveness to change even within the short period of a relapse.

The mean values as reported for items relating to burden in work life (items 26 and 27) indicate a substantial patient burden that has to be adequately taken into account when measuring the impact of relapses for people with MS, which is in line with previous results on patients’ treatment benefit.29 On the other hand, we found lower mean values for items relating to social life, such as “lack of understanding of others” or “limited social interaction.” Thus, these items might be less relevant in the context of a relapse.

Cronbach α of the MS-QLQ27 was high at both baseline (α = 0.94) and follow-up (α = 0.93), indicating excellent interrelatedness of items. Item-total correlations ranged from 0.4 to 0.7, except for item 4 “problems with eyesight” (r = 0.05), which indicates that the corresponding item did not correlate with the overall scale. However, visual dysfunction is one of the most common manifestations and very early symptom of RRMS, often resulting from acute demyelinating optic neuropathy but not correlated to other MS impairments. Approximately three-quarters of the sample reported problems with eyesight at baseline. Moreover, from the patient perspective, it is one of the symptoms most relevant for HRQOL.30 Thus, from a purely psychometric perspective, the item on problems with eyesight could be deleted. But because the MS-QLQ27 can be used in shared decision-making in clinical practice, where all relevant aspects of HRQOL should be included, we decided to keep all patient-relevant items in the questionnaire, including the problems with eyesight item.

To test for convergent validity, we hypothesized correlations of the MS-QLQ27 score with changes in other HRQOL measures. Hypothesis testing showed the expected directions and magnitudes of correlations. The responsiveness of the MS-QLQ27 is supported by highly significant correlations with improvement in disease-specific and generic HRQOL. As expected, stronger (and highly significant) correlations were found with the HAQUAMS than with the generic HRQOL measures. Known-groups validity was supported with respect to disability according to EDSS scores and short (≤5 years) versus long (>20 years) disease duration. Most importantly, the MS-QLQ27 showed the strongest effect size for responsiveness. A long-term study is necessary to depict the responsiveness through longer MS evolution.

Compared with the existing MS-specific HRQOL instruments, the MS-QLQ27 is, to our knowledge, the first to cover not only long-term burden but also relapse-related impairments in 2 aspects: first, in the item development, patients were explicitly asked to name relapse-related impairments; second, the instrument was tested for responsiveness to relapse treatment. In addition, the MS-QLQ27 is shorter than many of the existing instruments. As such, it lends itself to use for relapse treatment evaluation in clinical practice from the patient perspective. To our knowledge, it is also the only shorter instrument that covers work life and treatment burden, both of which are highly relevant aspects of HRQOL in patients with MS.6,13

One limitation of this study is that the sample includes only patients in current relapse, which restricts generalization to other MS populations. In addition to the excellent internal consistency found in this study, future research should assess test-retest reliability. Further investigations should focus on other patient groups, for example, those in remission, with secondary progressive MS, or with greater disease severity, to gain more information about the validity of the MS-QLQ27 in long-term MS treatment.

In conclusion, the MS-QLQ27 is a brief, reliable, valid, and responsive HRQOL questionnaire. It captures patient-relevant burden, including physical, mental, social, work, and treatment-specific aspects thereof, and is suitable for use in clinical practice and research.

PRACTICE POINTS

» The newly developed 27-item Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Questionnaire (MS-QLQ27) covers the important aspects of work- and treatment-related impact, which are neglected in other MS-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires.

» We found the MS-QLQ27 to be a reliable and valid instrument.

» The questionnaire was also responsive to change in neurologic status in the context of recovery from an MS relapse.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study and the Scientific Communication Team of the Institute for Health Services Research in Dermatology and Nursing (IVDP), University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), in particular Mathilda Meyer and Mario Gehoff, for copy editing.

References

Acquadro C, Perret C, Arnould B. Does health-related quality of life evaluation in multiple sclerosis (MS) matter? a review of labels of MS products approved by the FDA and EMA. Value Health. 2015;18(3):A288. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.03.1681

D’Amico E, Haase R, Ziemssen T. Review: patient-reported outcomes in multiple sclerosis care. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;33:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.05.019

Nowinski CJ, Miller DM, Cella D. Evolution of patient-reported outcomes and their role in multiple sclerosis clinical trials. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):934–944. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0571-6

Rudick RA, Miller DM. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: current evidence, measurement and effects of disease severity and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(10):827–839. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822100-00004

Berrigan LI, Fisk JD, Patten SB, . Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: direct and indirect effects of comorbidity. Neurology. 2016;86(15):1417–1424. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002564

Gil-González I, Martín-Rodríguez A, Conrad R, Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ. Quality of life in adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e041249. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041249

Pérez de Heredia-Torres M, Huertas-Hoyas E, Sánchez-Camarero C, . Occupational performance in multiple sclerosis and its relationship with quality of life and fatigue. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;56(2):148–154. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.05914-6

Lysandropoulos AP, Havrdova E, ParadigMS Group. “Hidden” factors influencing quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(suppl 2):28–33. doi: 10.1111/ene.12801

Maurino J, Martínez-Ginés ML, García-Domínguez JM, . Workplace difficulties, health-related quality of life, and perception of stigma from the perspective of patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;41:102046. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102046

Ross AP, Halper J, Harris CJ. Assessing relapses and response to relapse treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis: a nursing perspective. Int J MS Care. 2012;14(3):148–159. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073-14.3.148

Nickerson M, Cofield SS, Tyry T, . Impact of multiple sclerosis relapse: the NARCOMS participant perspective. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(3):234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2015.03.005

Citterio A, La Mantia L, Ciucci G, . Corticosteroids or ACTH for acute exacerbations in multiple sclerosis (updated 2013). Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2000.

Members of the MS in the 21st Century Steering Group, Rieckmann P, Centonze D, . Unmet needs, burden of treatment, and patient engagement in multiple sclerosis: a combined perspective from the MS in the 21st Century Steering Group. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;19:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2017.11.013

Tramacere I, Del Giovane C, Salanti G, . Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (9):CD011381. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011381.pub2

Cella DF, Dineen K, Arnason B, . Validation of the functional assessment of multiple sclerosis quality of life instrument. Neurology. 1996;47(1):129–139. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.1.129

Fischer JS, LaRocca NG, Miller DM, Ritvo PG, Andrews H, Paty D. Recent developments in the assessment of quality of life in multiple sclerosis (MS). Mult Scler. 1999;5(4):251–259. doi: 10.1177/135245859900500410

Simeoni M, Auquier P, Fernandez O, . Validation of the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life questionnaire. Mult Scler. 2008;14(2):219–230. doi: 10.1177/1352458507080733

Hobart JC, Riazi A, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, Thompson AJ. How responsive is the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29)? a comparison with some other self report scales. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(11):1539–1543. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.064584-1543

Gold SM, Heesen C, Schulz H, . Disease specific quality of life instruments in multiple sclerosis: validation of the Hamburg Quality of Life Questionnaire in Multiple Sclerosis (HAQUAMS). Mult Scler. 2001;7(2):119–130. doi: 10.1177/135245850100700208

Doward LC, McKenna SP, Meads DM, Twiss J, Eckert BJ. The development of patient-reported outcome indices for multiple sclerosis (PRIMUS). Mult Scler. 2009;15(9):1092–1102. doi: 10.1177/1352458509106513

Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Harooni R, Myers LW, Ellison GW. A health-related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(3):187–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02260859

Khurana V, Sharma H, Afroz N, Callan A, Medin J. Patient-reported outcomes in multiple sclerosis: a systematic comparison of available measures. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(9):1099–1107. doi: 10.1111/ene.13339

Galea I, Ward-Abel N, Heesen C. Relapse in multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2015;350:h1765. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1765

EuroQol Group. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168 -8510(90)90421-9

Graf JM, Claes C, Greiner W, . Die deutsche Version des EuroQol-Fragebogens. Z f Gesundheitswiss. 1998;6:3–20. doi.org/10.1007/BF02956350

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, . The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444

Matza LS, Kim K, Phillips G, . Multiple sclerosis relapse: qualitative findings from clinician and patient interviews. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;27:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.09.029

Beckmann H, Augustin M, Heesen C, Poettgen J, Blome C. Benefit evaluation in multiple sclerosis relapse treatment from the patients’ perspective: development and validation of a new questionnaire. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;28:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.12.021

Heesen C, Böhm J, Reich C, Kasper J, Goebel M, Gold SM. Patient perception of bodily functions in multiple sclerosis: gait and visual function are the most valuable. Mult Scler. 2008;14(7):988–991. doi: 10.1177/1352458508088916

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study was funded in part by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant 01EH1101B).

PRIOR PRESENTATION: The material was exhibited as a poster presentation at the 25th Annual Conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research; October 24-27, 2018; Dublin, Ireland.