Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Self-Reported Burden Among Caregivers of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) are chronic and progressive diseases that may impose a significant burden on caregivers and patients' immediate families. Extensive research shows MS and AD caregiver burden on physical and mental health, but no direct comparisons between MS and AD caregivers have been reported in the literature. The objective of this study was to examine the extent of MS caregiver burden compared with that of noncaregivers and AD caregivers. Data were obtained from the 2009 National Health and Wellness Survey administered online to a US representative adult sample (N = 75,000). Respondents reported health status, quality of life, work productivity, health-care utilization, and caregiver status. Multivariable regressions, adjusting for key characteristics (eg, age, gender, marital status, depression), were conducted to explore differences between MS caregivers (n = 215) and noncaregivers (n = 69,224) and between MS caregivers and AD caregivers (n = 1341). The results indicated that MS caregivers had significantly greater activity impairment (P = .01), poorer mental (P = .015) and physical (P = .002) health status, lower health utility scores (P = .002), and more traditional health-care provider visits (P < .001), emergency room (ER) visits (P < .001), and hospitalizations (P = .001) than noncaregivers, adjusting for covariates. After adjustments, MS caregivers had greater activity impairment (P = .044), more ER visits (P = .017), and more hospitalizations (P = .008) than AD caregivers. Significant work productivity differences were not observed across groups, possibly owing to fewer employed respondents. Thus, in this study, MS caregivers had significantly more burden than noncaregivers, and for some measures, even AD caregivers. The results reveal the hidden toll on those providing care for MS patients and highlight the need for health-care providers to recognize their burden so that appropriate measures can be implemented.

Providing care to a person with a chronic disease can have significant effects on the caregiver. The term caregiver burden is used to describe the negative impacts on the caregiver of providing care to a patient.1–3 Previous research has shown that just as dealing with a disease has negative impacts on a patient, the activities and engagement associated with caring for that patient can impose burdens on an individual providing care.2–5

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurodegenerative disease in which the immune system attacks the central nervous system, causing a wide range of physical, psychological, and cognitive symptoms.6 Symptoms of MS patients include mobility problems, bladder dysfunction, pain, depression, and cognitive changes.7 These symptoms often affect the patient's ability to engage in day-to-day activities and increase the patient's reliance on caregivers.

A number of studies have shown that providing care for MS patients affects the physical,8–11 financial,12 psychological,8 and social12 13 well-being of the caregiver. The extent of the burden is dependent on the severity of the patient's symptoms8–10 14–16 and the duration of the patient's illness.17 18 Recent research has shown that as the number of caregiving hours per week increased, caregiver burden increased as well.7 Other research reported that caregiver burden has a reciprocal effect on the patient, causing patient distress and straining the relationship between caregiver and patient.18–21

Comparisons between MS caregivers and noncaregiver controls allow for better overall understanding of the psychological and physical burdens distinct to caregiving. Caregivers of people with MS have been found to have higher anxiety and stress than noncaregiver controls.22 23 Alshubaili et al.24 demonstrated that MS caregivers had lower quality of life (QOL) than a general-population control group. The study also found significant differences in the social relations and spirituality QOL domains among MS caregivers as well as a significantly lower general score for QOL and health, even after controlling for patients' depression and disability.

In addition to comparing MS caregivers with noncaregiver controls, it is useful to compare MS caregivers with caregivers of patients with other chronic conditions. Alzheimer's disease (AD) has many similarities to MS, as they are both neurodegenerative diseases without a cure that can lead to significant levels of impairment. Caregivers of people with AD also report burden that affects their physical,25 26 financial,27 28 psychological,29 30 and social31 well-being. The burden of AD caregivers thus provides a useful benchmark against which to compare the specific level of burden experienced by MS caregivers, further elucidating how MS affects caregiver well-being. To date, no reported studies have directly compared caregiver burden between MS and AD caregivers. Forbes et al.9 suggested that caregiver well-being may be similar across caregivers for patients with chronic diseases, although no direct comparison was made between an MS sample and another chronic disease sample.

The present study aimed to characterize MS caregiver burden by examining health-related quality of life (HRQOL), work productivity, activity impairment, and health-care utilization. To this end, comparisons were made between caregivers of MS patients and noncaregiver controls, and between caregivers of MS patients and caregivers of AD patients. The comparison between MS caregivers and noncaregiving controls was selected because of the mixed or incomplete evidence on burden of MS caregiving in the literature. The comparison between MS caregivers and AD caregivers was considered useful because both groups care for patients with chronic, progressive diseases that have significant effects on the patients. Finally, this study aimed to remedy the lack of generalizability in many prior studies by using a sample obtained from a larger, nationally representative survey.

Methods

Data Source

The US National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) is a self-administered online survey of 75,000 adults aged 18 years or older conducted on an annual basis. Participants are recruited through an Internet panel (Lightspeed Research). A stratified random sampling procedure was implemented to ensure that the demographic composition and geographic distribution of the responders were equivalent to those of the US population. The NHWS is a proprietary, cross-sectional assessment of demographics, health-care attitudes and behaviors, disease status, and health outcomes. All data were self-reported directly by patients. The NHWS questionnaire and study protocol were approved by an institutional review board (Lebanon, NJ). Informed consent was obtained from respondents before administration of the survey. Participants were compensated with program points that could be accumulated across panel surveys and used in exchange for gifts.

Study Sample

Data from the 2009 US NHWS sample (total N = 75,000) were used to compare noncaregivers (n = 69,224) with MS caregivers (n = 215), and MS caregivers with AD caregivers (n = 1341). The MS and AD caregiver groups were mutually exclusive. Analyses reported below include respondents who reported being caregivers for MS or AD patients, but not for patients with any other condition. For three of the four components of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI)32 metrics, only respondents who were employed (full time, part time, or self-employed) at the time they completed the survey were included (total employed: n = 40,258; noncaregiver controls: n = 37,305; MS caregivers: n = 126; AD caregivers: n = 699).

Study Measures

Demographic characteristics included age as a continuous variable, gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other including Asian respondents), marital status (married/living with partner, divorced/separated/widowed, single), education (more than high school vs. high school equivalent degree or less), income (<$25K, $25K to <$50K, $50K to <$75K, $75K+, or declined to answer), employment status (full time, part time, self-employed, or other), and health insurance status (yes or no).

Health status variables assessed included current smoking status, exercise status, alcohol use, body mass index (BMI) (underweight, normal, overweight, obese, or declined to answer), the two-item Whooley depression screener33 for major depressive disorder (score ≥1 indicates possible depression), and the adjusted Charlson comorbidity index (CCI).34 The adjusted CCI attempts to mimic the CCI via a weighted sum of comorbidities in which the presence of each of several physical health symptoms or diseases such as HIV/AIDS, metastatic tumor, lymphoma, ulcer disease, connective tissue disease, and chronic pulmonary disease is weighted by its respective contribution to mortality risk. The greater the total index score, the greater the comorbid burden on the patient.

Dependent Measures

Work productivity was measured with the general health version of the WPAI questionnaire. Three of the four components (absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment) were used only with the employed subsample; the fourth component (activity impairment) was used with the entire sample. Higher values on each WPAI component indicate greater impairment and are generated in the form of percentages. These four components are operationalized as:

Absenteeism (percent work time missed due to health in the past 7 days)

Presenteeism (percent impairment due to health experienced while working in the past 7 days)

Overall work productivity loss (percent overall work impairment experienced due to health in the past 7 days)

Activity impairment (percent impairment during daily activities experienced due to health in the past 7 days)

Health-related quality of life was assessed using the Physical (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores from the 12-item Short Form Health Status Survey (SF-12), version 2,35 as well as the health utility measure derived from it, the Short Form–6D (SF-6D). The PCS and MCS scores are normed to the US population (mean = 50, SD = 10), with higher scores indicating greater HRQOL. The health utility score is a preference-based single index measure for health using general population values. These scores have interval scoring properties and yield summary scores on a scale of 0 to 1, where 0 is equivalent to death and 1 is equivalent to perfect health.

Health-care utilization was operationalized by asking about number of traditional health-care provider visits (eg, neurologist, general practitioner, psychiatrist/psychologist), number of visits to a nontraditional provider (eg, acupuncturist, chiropractor, nutritionist), taking a prescribed medication, number of emergency room (ER) visits (“How many times have you been to the ER for your own medical condition in the past 6 months?”), and the number of times hospitalized in the past 6 months (“How many times have you been hospitalized for your own medical condition in the past 6 months?”).

Statistical Analyses

To analyze demographic, health status, and unadjusted health outcome differences between MS caregivers and noncaregiver controls and between MS and AD caregivers, bivariate analyses were performed. Chi-square tests were used with categorical variables, and independent-samples t tests were used with continuous variables.

Adjusted comparisons between groups (ie, MS caregivers vs. noncaregivers; MS vs. AD caregivers) were performed using a series of generalized linear regression models (GLMs) with normal or negative binomial (to account for the skewed characteristics of the WPAI and health-care utilization variables) distributions. These GLMs adjusted for the following key covariates: age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, income, smoking status, exercise, alcohol use, employment type, health insurance, depression (Whooley scale), and comorbidity (adjusted CCI) as defined above. For all multivariable models, statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

MS Caregivers vs. Noncaregivers Bivariate Comparisons

Demographic Variables

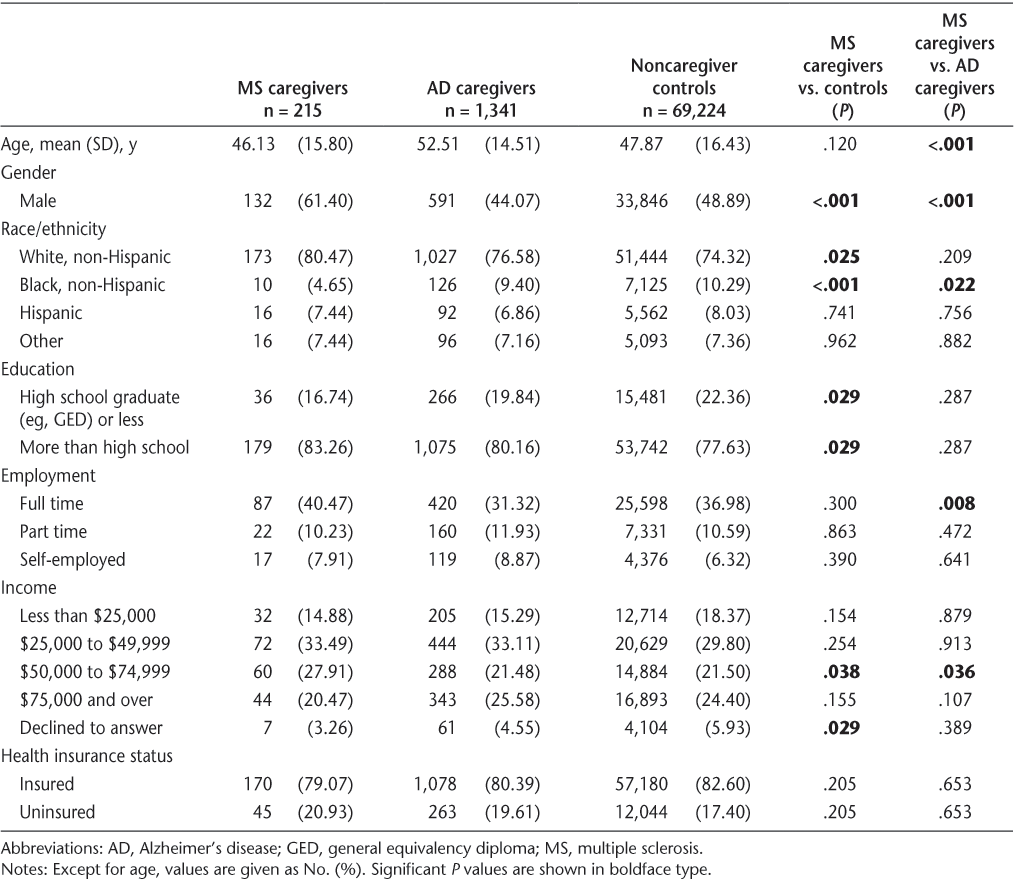

Bivariate results revealed that MS caregivers were similar in age to noncaregiver controls (mean age, 46.1 vs. 47.9 years, respectively; P = .120). MS caregivers reported a higher proportion of males than noncaregivers (61.4% vs. 48.9%, respectively; P < .001). MS caregivers were more likely to be white (80.5% vs. 74.3%, P < .05) and less likely to be black (4.7% vs. 10.3%, P < .001) than noncaregivers. They were also more educated than noncaregivers, being more likely to have an education beyond high school (83.3% vs. 77.6%, P < .05). MS caregivers were also more likely to have an income in the $50,000 to $74,999 range than noncaregivers (27.9% vs. 21.5%, P < .05). No other significant demographic differences emerged between MS caregivers and noncaregivers (Table 1).

Demographic information for MS caregivers, AD caregivers, and noncaregiver controls

Health Status Information

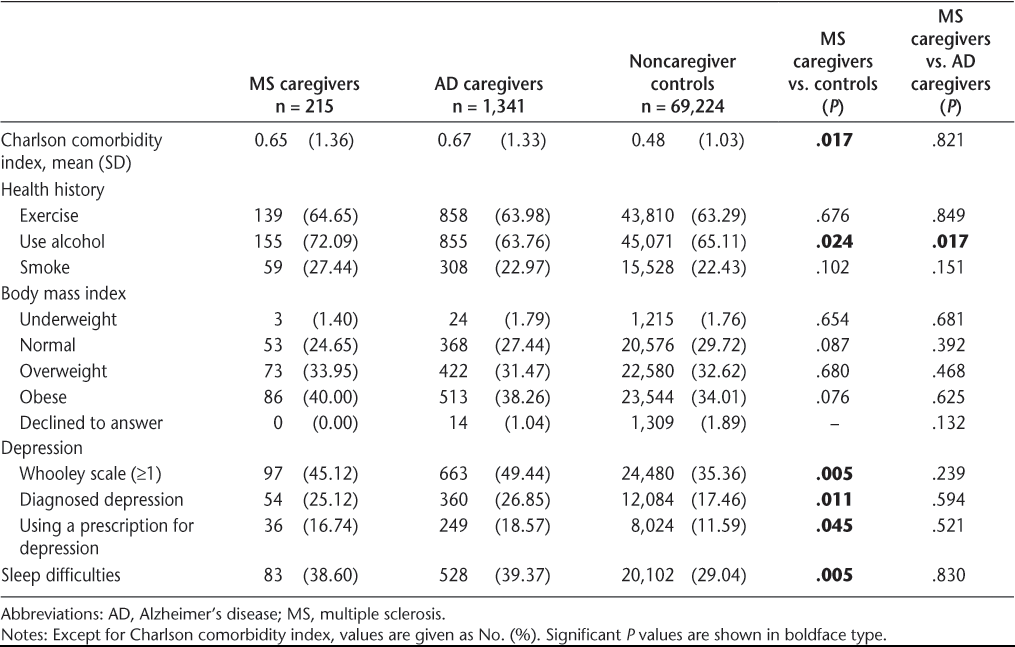

Charlson comorbidity index scores were higher among MS caregivers than among noncaregivers (mean score of 0.65 vs. 0.48, respectively; P < .05). Alcohol use was higher among MS caregivers than among noncaregivers (72.1% vs. 65.1%, P < .05). Compared with noncaregivers, greater proportions of MS caregivers scored ≥1 on the Whooley scale, reported having received a diagnosis of depression from a physician, and were using a prescription to treat depression (all P < .05). MS caregivers also reported more sleep difficulties than noncaregivers (38.6% vs. 29.0%, respectively; P < .01). MS caregivers and noncaregivers did not differ significantly in their self-reported exercise and smoking behavior (Table 2).

Health status information for MS caregivers, AD caregivers, and noncaregiver controls

WPAI

Among employed respondents, MS caregivers reported a greater proportion of missed work time (absenteeism), a greater proportion of impairment at work (presenteeism), more hours missed due to impairment at work, and a greater proportion of overall work impairment compared with noncaregivers (all P < .05). MS caregivers and noncaregivers did not differ significantly in hours of work missed. MS caregivers reported over 10% more activity impairment than noncaregivers (Table 3).

Unadjusted health outcomes for MS caregivers, AD caregivers, and noncaregiver controls

HRQOL

MS caregivers reported significantly lower HRQOL than noncaregivers, across all HRQOL measures (MCS, 44.9 vs. 47.9, respectively; PCS, 45.4 vs. 47.6; and health utilities, 0.70 vs. 0.74; all P < .01) (Table 3).

Health-Care Utilization

A higher proportion of MS caregivers reported visiting a traditional health-care provider (88.4% vs. 78.5%, P < .001), using a prescription medication (80.5% vs. 70.3%, P < .001), and hospitalization (15.8% vs. 7.5%, P = .001) compared with noncaregivers. In addition, MS caregivers were more likely to report a visit to a nontraditional health-care provider or an ER visit compared with noncaregivers (all P < .01) (Table 3).

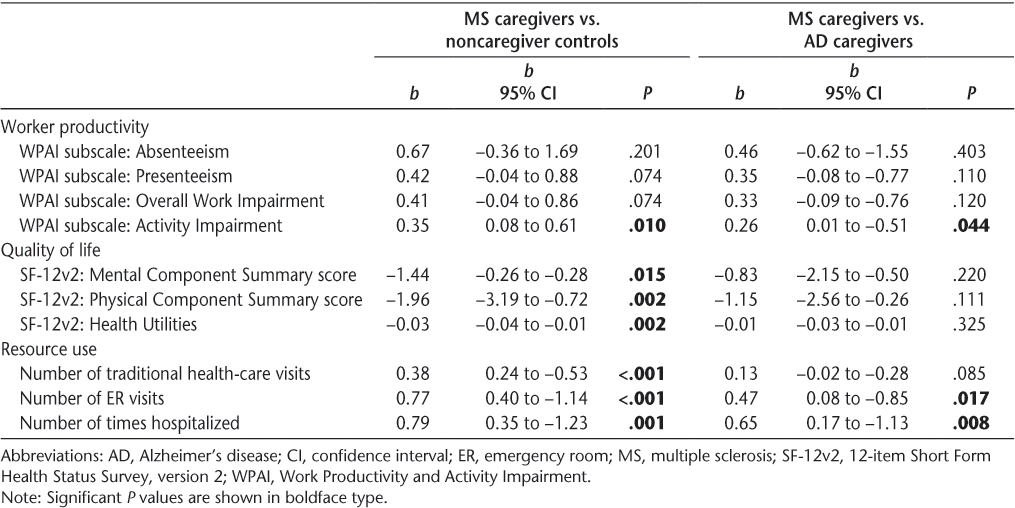

MS Caregivers vs. Noncaregivers Multivariable Results

Adjusted comparisons from the multivariable regressions were generally consistent with the bivariate results. MS caregivers reported lower adjusted mean MCS (−1.4 points), PCS (−2.0 points), and health utility (−0.03 points) scores than noncaregivers (all P < .05). MS caregivers reported greater activity impairment (P = .01) than the noncaregiver controls, but no significant differences were found for absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment. The MS caregivers also had significantly more traditional health-care provider visits, ER visits, and hospitalizations than noncaregiver controls (all P < .01) (Table 4).

Multivariable regression results for work productivity, quality of life, and health-care resource use

MS vs. AD Caregivers Bivariate Comparisons

Demographic Variables

MS caregivers were younger than AD caregivers, with mean ages of 46.1 and 52.5 years, respectively (P < .001) and more likely to be male (61.4% vs. 44.1%, P < .001). They were also more likely to be currently employed full time (40.5% vs. 31.3%, respectively; P < .01). MS caregivers were less likely to be black than AD caregivers (4.7% vs. 9.4%, P < .05), and more likely to have an income in the $50,000 to $74,999 range than AD caregivers (27.9% vs. 21.5%, P < .05). No other significant demographic differences emerged between MS and AD caregivers (Table 1).

Health Status Information

There was no significant difference in CCI scores between MS caregivers and AD caregivers; however, it was noted that 6% of MS caregivers reported having MS and 0.08% reported having AD, while 1% of AD caregivers had MS and 0.6% had AD. MS caregivers reported consuming alcohol more often than AD caregivers (72.1% vs. 63.8%, respectively; P < .05). No other significant differences in health status emerged between MS and AD caregivers (all P > .05) (Table 2).

WPAI

MS caregivers reported higher percentage levels of activity impairment in the past 7 days than AD caregivers (35.4% vs. 29.6%, respectively; P < .01). MS and AD caregivers did not differ significantly on any other WPAI components (Table 3).

HRQOL

No significant differences between MS and AD caregivers were observed on any HRQOL measures (Table 3).

Health-Care Utilization

A higher proportion of MS than AD caregivers reported an ER visit (21.9% vs. 15.7%, respectively; P < .05) or a hospitalization (15.8% vs. 8.6%, respectively; P = .001). No other significant differences in health-care utilization emerged between MS and AD caregivers (Table 3).

MS vs. AD Caregivers Multivariable Results

Adjusted comparisons from the multivariable regressions were consistent with the bivariate results. Adjusting for covariates, MS caregivers had greater activity impairment (P < .05), more ER visits (P < .05), and more hospitalizations (P < .01) than AD caregivers. MS caregivers and AD caregivers showed no significant differences on MCS, PCS, or health utility scores, as well as no significant differences on the other WPAI components (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study examined self-reported data from MS caregivers, AD caregivers, and noncaregivers to elucidate their psychological and physical well-being. Overall, we found that MS caregivers reported poorer physical and psychological health in comparison with noncaregivers. In addition, MS caregivers reported similar levels of physical and psychological functioning to those of AD caregivers; however, a few key differences emerged between MS caregivers and AD caregivers in terms of health-care resource use and activity impairment.

This study clarified a range of differences between MS caregivers and noncaregiver controls. MS caregivers had lower HRQOL scores, greater health-care utilization, and greater activity impairment than noncaregivers. In contrast to research by Vedhara et al.,23 which showed limited differences in anxiety and depression between MS caregivers and noncaregivers, our sample of MS caregivers reported poorer mental and physical health than noncaregiver controls. The current sample was larger (n = 215 vs. n = 41) and slightly older (mean age, 46 years vs. 43 years); therefore, our results may reflect the larger sample size with more statistical power to detect significant differences among outcome measures. In addition, although we do not have data on age or level of disability of the MS patients for whom the caregivers were providing care, our sample could be caring for patients with longer disease progression, which previous research has shown adversely affects the mental and physical health of MS caregivers.7

In this study, MS caregivers reported greater activity impairment than noncaregiver controls. Perhaps not surprisingly, recent research showed that restriction of the MS caregivers' important daily activities increases caregiver burden.7 Even though MS caregivers had greater activity impairment than noncaregivers, MS caregivers and noncaregivers did not differ on work hours missed, which may be due to the lower number of employed MS caregivers. At the bivariate level, MS caregivers reported higher levels of impairment while working and overall impairment due to health. Given the financial difficulties often reported by families of people with MS,12 MS caregivers may feel compelled not to miss work but nonetheless experience impairment while at work.

Also in comparison with noncaregivers, MS caregivers had more health-care provider visits, ER visits, and hospitalizations. Their lower levels of mental and physical health could contribute to this increase in seeking health care. In a qualitative study,24 fear of having MS in the future was related to a decrease in QOL for caregivers. The risk of acquiring MS is higher in relatives of a person with the disease, especially among immediate family members.36 In our study, 6% of MS caregivers reported having MS, which may result in increased health-care utilization.

Our study also compared MS caregivers with AD caregivers. MS and AD caregivers experienced similar levels of mental and physical health, but MS caregivers had higher activity impairment and health-care resource use. MS caregivers were more likely to have ER visits and to be hospitalized than AD caregivers. As previously mentioned, there was a proportion of MS caregivers who reported having MS. This finding may have had some effect on the differences in health-care utilization that were observed. However, since no other reported studies have compared MS caregivers with AD caregivers, it is difficult to determine specific reasons why MS caregivers may be utilizing health-care resources more often than AD caregivers.

Although caring for both MS and AD patients affects the well-being of caregivers, differences in the onset of MS and AD suggest that the two diseases may affect different facets of caregiver burden. For example, the onset of MS is typically when the patient is in his or her 20s to early 40s, whereas the onset of AD is typically in the patients' 60s.36 37 MS caregivers may therefore experience greater financial burden than AD caregivers, as they are more likely to have young children in the home and may not be as financially secure or as developed in their careers as AD caregivers.6 This may be true in spite of studies showing that AD caregivers face their own indirect economic costs of caregiving, including loss of time and productivity.38–40 Future studies, stratifying by age groups, may improve our understanding of how the developmental trajectory of patients' deterioration in functioning degrades the mental, physical, and financial well-being of caregivers.

Study Limitations

Although this study makes important strides in further understanding the burden of MS caregivers, it has limitations. All responses were self-reported via an online survey, and thus respondents without Internet or computer access were not represented in the current sample. Also, owing to study design, there is no direct means of validating caregivers' reports of mental and physical problems against external sources. Although the sample was generally representative of the US population, sampling did not specifically ensure the representativeness of MS or AD caregivers, as the sample size for MS caregivers was considerably smaller than those for AD caregivers and noncaregiver controls. The noncaregiver control group sample was much larger than both the MS and AD caregiver groups. Therefore, results may not be generalizable to all MS and AD caregivers.

Another limitation is that, despite the inclusion of many covariates in the models, other relevant covariates may not have been measured or assessed. For example, although the CCI was included in the models, the presence of MS or AD in caregivers was not specifically adjusted for, as the objective of this study was to assess the impact on caregivers, regardless of specific comorbidities. In addition, other factors such as the patient's disease severity and associated disability and the nature of the caregiver's relationship to the patient, both of which could have a significant impact on caregiver burden, were not assessed in this study. The relationships between MS and AD caregiving and productivity loss should be considered associative rather than causal because the version of the WPAI used in this study asked about impairment generally and not specifically related to MS or AD. Adjusting for covariates in analyses helped to attribute the variance in health outcomes across groups to the independent effect of caregiving. Nevertheless, higher resource utilization cannot be attributed exclusively to MS or AD caregiving, because survey questions did not reference caregiving specifically as the cause of resource use. Causality cannot be established with the current study design.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that MS caregivers experience poorer mental and physical health-related outcomes than noncaregivers. Buchanan et al.7 suggested addressing the psychological needs of MS caregivers; however, the current article highlights the need to further address the medical needs of MS caregivers as well, as they report a higher level of health-care resource utilization than do either noncaregiver controls or AD caregivers. This research, based on results from a national survey, highlights areas that merit further attention by health-care providers—namely, they need to be aware of the physical and mental burden that can accompany caregiving for a patient with a chronic debilitating disease. Recognizing the complete (and often hidden) toll on those providing care for MS patients can enable the implementation of a more appropriate, comprehensive approach to MS care.

PracticePoints

Caregivers of people with MS experience a high degree of burden compared with noncaregiver controls.

MS caregivers experience similar impacts on health-related quality of life as Alzheimer's disease caregivers but report more activity impairment and greater resource use.

This research highlights the need for health-care providers to address the mental and physical burden on MS caregivers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jarret Crawford and Amber Emanuel for assistance with the literature review. Dr. Crawford and Ms. Emanuel are consultants to Kantar Health.

References

George LK, Gwyther LP. Caregiver well-being: a multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. Gerontologist. 1986; 26: 253–259.

McGuire T, Wells KB, Bruce ML, et al. Burden of illness. Ment Health Serv Res. 2002; 4: 179–185.

Brown ML, Lipscomb J, Snyder C. The burden of illness of cancer: economic cost and quality of life. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001; 22: 91–113.

Bevans M, Sternberg EM. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA. 2012; 307: 398–403.

Banaszkiewicz K, Sitek EJ, Rudzińska M, SoŁtan W, SŁawek J, Szczudlik A. Huntington's disease from the patient, caregiver and physician's perspectives: three sides of the same coin? J Neural Transm. 2012; 119: 1361–1365.

Mohr DC, Cox D. Multiple sclerosis: empirical literature for the clinical health psychologist. J Clin Psychol. 2001; 57: 479–499.

Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Huang C. Caregiver burden among informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2011; 13: 76–83.

Figved N, Myhr KM, Larsen JP, Aarsland D. Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis: the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007; 78: 1097–1102.

Forbes A, While A, Mathes L. Informal carer activities, carer burden and health status in multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2007; 21: 563–575.

Groom MJ, Lincoln NB, Francis VM, Stephan TF. Assessing mood in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2003; 17: 847–857.

Pakenham KI. Relations between coping and positive and negative outcomes in carers of persons with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2005; 12: 25–38.

DeJubicibus MA, McCabe M. Economic deprivation and its effects on subjective wellbeing in families of people with multiple sclerosis. J Ment Health. 2005; 14: 49–59.

Khan F, Pallant J, Brand C. Caregiver strain and factors associated with caregiver self-efficacy and quality of life in a community cohort with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2007; 29: 1241–1250.

Chipchase SY, Lincoln NB. Factors associated with carer strain in carers of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2001; 23: 768–776.

Morales-Gonzales JM, Benito-Leon J, Rivera-Navarro J, Mitchell AJ; GEDMA study group. A systematic approach to analyse health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the GEDMA study. Mult Scler. 2004; 10: 47–54.

Sherman TE, Rapport LJ, Hanks RA, et al. Predictors of well-being among significant others of persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 238–249.

Rivera-Navarro J, Morales-Gonzales JM, Benito-Leon J. Informal caregiving in multiple sclerosis patients: data from the Madrid Demyelinating Disease Group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2003; 25: 1057–1064.

Pozzilli C, Palmisano L, Mainero C, et al. Relationship between emotional distress in caregivers and health status in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004; 10: 442–446.

Kleiboer AM, Kuijer RG, Hox JJ, Schreurs KMG, Bensing JM. Receiving and providing support in couples dealing with multiple sclerosis: a diary study using an equity perspective. Pers Relat. 2006; 13: 485–501.

Kleiboer AM, Kuijer RG, Hox JJ, Jongen PJH, Frequin STFM, Bensing JM. Daily negative interactions and mood among patients and partners dealing with multiple sclerosis (MS): the moderating effects of emotional support. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 64: 389–400.

Perrone KM, Gordon PA, Tschopp MK. Caregiver marital satisfaction when a spouse has multiple sclerosis. J Appl Rehabil Counsel. 2006; 37: 26–32.

Janssens AC, van Doorn PA, de Boer JB, van der Meche FGA, Passchier J, Hintzen RQ. Impact of recently diagnosed multiple sclerosis on quality of life, anxiety, depression and distress of patients and partners. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003; 108: 389–395.

Vedhara K, McDermott MP, Evans TG, et al. Chronic stress in non-elderly caregivers: psychological, endocrine and immune implications. J Psychosom Res. 2002; 53: 1153–1161.

Alshubaili AF, Ohaeri JU, Awadalla AW, Mabrouk AA. Family caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis among Kuwaitis: a controlled study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008; 8:206.

Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiving Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999; 282: 2215–2219.

Fuller-Jonap F, Haley WE. Mental and physical health of male caregivers of a spouse with Alzheimer's disease. J Aging Health. 1995; 7: 99–118.

Langa KM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, et al. National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16: 770–778.

Nicolaou PL, Egan SJ, Gasson N, Kane RT. Identifying needs, burden, and distress of carers of people with frontotemporal dementia compared to Alzheimer's disease. Dementia. 2010; 9: 215–235.

Kolanowski AM, Fick D, Waller JL, et al. Spouses of persons with dementia: their healthcare problems, utilization, and costs. Res Nurs Health. 2004; 27: 296–306.

Lu YY, Wykle M. Relationships between caregiver stress and self-care behaviors in response to symptoms. Clin Nurs Res. 2007; 16: 29–43.

Beeson R, Horton-Deutsch S, Farran C, Neurndorfer M. Loneliness and depression in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease or related disorders. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 2000; 21: 779–906.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993; 4: 353–365.

Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression: two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997; 12: 439–445.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987; 40: 373–383.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, et al. SF-12v2™: How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12® Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc; 2002.

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008; 372: 1502–1517.

Brookmeyer R, Gray S, Kawas C. Projections of Alzheimer's disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. Am J Public Health. 1998; 88: 1337–1342.

Rice DP, Fox PJ, Max W, et al. The economic burden of Alzheimer's disease care. Health Affairs. 1993; 12: 164–176.

Leon J, Cheng CK, Neumann PJ. Alzheimer's disease care: costs and potential savings. Health Affairs. 1998; 17: 206–216.

Weinberger M, Gold DT, Divine GW, et al. Expenditures in caring for patients with dementia who live at home. Am J Public Health. 1993; 83: 338–341.

Financial Disclosures/Funding: The National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) is conducted by Kantar Health. EMD Serono and Pfizer purchased access to the NHWS dataset and funded the analysis and preparation of this manuscript.