Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Recruiting for Caregiver Education Research

Author(s):

Caregiver education programs can support participants in a role that is often challenging. Research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these programs; however, recruitment for such studies can be difficult. The objectives of this study were to explore 1) how multiple sclerosis (MS) caregivers respond to recruitment materials for a research study evaluating a caregiver education program, including aspects of the materials that encourage or discourage their interest in participation; and 2) what recommendations MS caregivers have for improving study recruitment advertising. Qualitative interviews were conducted with seven MS caregivers. Participants were asked about their reactions to advertisements for a pilot study intended to evaluate an MS caregiver education program. Participants were also asked to reflect on factors that would influence their decision to participate in the program and to provide suggestions to improve recruitment materials. Data were analyzed using a constant-comparative approach. Study findings indicated that the language and visual design of the advertisements influenced the participants' initial responses. Some caregivers first responded to the fact that the program was part of a research study, and these caregivers had overall negative responses to the advertising, such as concern that the program was being “tested.” Other caregivers first considered the personal relevance of the program. These caregivers had neutral-to-positive responses to the flyers and weighed the relevance of the program against the research and logistical aspects. Participants provided recommendations to improve the recruitment materials. While recruiting for caregiver education research can be challenging, piloting recruitment materials and using a variety of advertising options may improve response.

Older adults with disabilities who live in the community often require assistance with everyday tasks such as basic activities of daily living (eg, bathing, dressing), mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living.1 Most often, this assistance is provided by an unpaid caregiver such as a family member or friend.2 The care provided by these unpaid caregivers significantly decreases the use of formal health-care resources3 and enables care recipients to remain in the community.4 However, caregiving can have negative effects on caregivers' physical, social, emotional, and financial health and well-being.5–8 These effects and their potential consequences for care recipients have led to an ongoing interest in developing and evaluating ways to support caregivers through educational programming,9 10 support groups,11 12 respite programs,13 and one-to-one counseling.14

Several research studies have tested the efficacy and effectiveness of caregiver education programs for caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease,15–17 cancer,18 19 and stroke.20 Some of the more common objectives across these programs include promoting the overall health and well-being of caregivers, helping them develop practical skills so they can perform their caregiving tasks more effectively, and increasing their self-efficacy and resilience to better manage the challenges they face. Program formats typically include a series of weekly closed-group meetings, each lasting around 2 hours,15 17 20 although some programs involve only a single contact.18 19

Program topics in caregiver education programs vary and can be grouped into three broad areas. First, such programs often aim to help participants cope more effectively with change and manage competing responsibilities and stressors,16 often through the application of problem-solving strategies.18 Second, these programs help caregivers develop skills to obtain necessary support15 19 and find and use resources.15 16 19 Finally, caregiver education programs address a broad spectrum of care,16 acknowledging that participants are dealing with the emotional and physical responses to care16 as well as managing specific symptoms experienced by care recipients.15 Key reported outcomes across these studies have included feeling less enmeshed in care and feeling a decreased need to control the care recipient's behavior17; improvements in communication and health practices15; improvements in caregivers' abilities to provide care and access community resources18; and increased knowledge of specific conditions (eg, stroke).20

Despite the success of many caregiver education programs,15 17 18 20 one common problem has been recruiting participants for caregiver education research.21 Researchers have used a variety of recruitment strategies including convenience sampling, open enrollment, and referral by professionals, but still frequently report encountering problems recruiting participants.19 20 During a pilot study for an education and self-management program targeting caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis (MS), we experienced similar recruitment challenges despite having used a variety of recruitment strategies (eg, flyers distributed through MS support groups, in public places, and through health-care professionals; announcements in MS society newsletters and local newspapers and on local radio stations; and direct mailing to members of the local MS society).22 As a result, the research team questioned whether specific features of the advertising influenced caregivers' willingness to participate in the study. An additional study was conducted to better understand caregivers' reactions to the study advertisement, and its results are described here. This article describes an exploratory descriptive study using qualitative interviews through which we sought to address the following questions:

1) How do caregivers respond to study recruitment materials?

What aspects of the caregiver study recruitment materials encourage individuals to seek more information about participation?

What aspects of the caregiver recruitment materials discourage individuals from seeking more information about participation?

2) What recommendations do MS caregivers have for improving study recruitment materials?

Methods

Recruitment and Sampling

Two primary methods were used to recruit MS caregivers for this study. First, 21 caregivers who had originally contacted the study office to inquire about participating in the caregiver education pilot study, but either chose not to participate or were unable to participate because of logistical issues, were invited by letter to participate. In the letter of invitation, we explained that the purpose of the exploratory study was to gather different perspectives on what attracts or does not attract caregivers of people with MS to studies involving caregiver education programs, and what factors influence their decisions to attend programs that are part of research studies. We also described what would be involved in participating, and asked interested individuals to contact the study office. Second, flyers about the study were distributed through contacts at the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and MS support groups. Individuals receiving the flyers were encouraged to distribute them to other people they knew who might be interested in being interviewed.

Through these recruitment strategies, individuals who were interested contacted the study office. The only eligibility criteria were 1) being a caregiver to a person with MS, and 2) willingness to engage in an interview for 30 to 60 minutes either on the telephone or in person, according to participant preference, at a mutually convenient time (and location, if in person). A total of seven people expressed interest in participating, and all were interviewed. Demographic information about the participants is described in the Results section.

Consent Process

The consent process was managed in two ways depending on whether the interview was conducted by telephone or in person. For interviews that were conducted by telephone, two copies of the consent document were mailed to the prospective participant to review, sign, and return. Once the form was received, the interview was scheduled. At the beginning of the call, the interviewer reviewed the consent form, answered questions, confirmed consent, and then proceeded with the interview. The researchers interviewed three individuals by telephone.

For interviews that were conducted in person, a date, time, and location were arranged for the interview. At the beginning of the meeting, the interviewer reviewed the consent form, answered questions, and asked the interviewee to sign the form if he or she was still willing to be interviewed. The interviewer gave a copy of the consent form to the participant. The researchers interviewed four individuals in person. The human subjects review board of our university reviewed and approved these procedures.

Interview

A single, in-depth interview was completed with each participant. Because the goal of the study was to explore the responses of caregivers to the study advertising, we used a modified form of cognitive interviewing to develop the interview guide. Cognitive interviewing was originally designed to evaluate sources of response error in survey questionnaires.23 As originally designed and used, cognitive interviewing allows a researcher to determine the extent to which a participant understands a survey item and is able to retrieve relevant information to respond to the item, respond truthfully to the item, and match his or her responses to the available response options. There are two basic subtypes of cognitive interviewing—“think-aloud” interviews and verbal probing. Both methods seek to access respondents' cognitive processes as they respond to the survey items.23

In the context of this study, we wanted caregivers to share their understanding of the recruitment materials, identify what components of the materials were relevant to them, and indicate whether or not the materials would lead them to seek more information about the study and/or volunteer to participate. Therefore, while we were not evaluating sources of response error, we were evaluating the extent to which the wording, language, and format of the recruitment materials contributed to caregivers' responses to them. We used both think-aloud queries and verbal probing to encourage caregivers to share their responses to three different versions of the program advertising.

The interviewer provided the advertisements to the caregivers in a specific sequence: 1) short-form flyer, 2) long-form/detailed flyer, 3) public service announcement. The short-form flyer included the title of the project, an empty box in the upper right-hand corner for the institutional review board approval stamp, very basic information about the research study, and pull tabs with the contact information for the research office. The long-form/detailed flyer included the title of the project, an empty box in the upper right-hand corner for the institutional review board approval stamp, detailed information about the study (purpose, eligibility criteria, what participation would involve), and contact information for the research office. The public service announcement was a written version of the one-paragraph announcement that was broadcast on the radio.

For participants who were interviewed by telephone, the materials were sent to the participant in advance of the call so that he or she could refer to them during the interview. Sample questions included the following: What is your response to this (advertisement/flyer)? What questions, thoughts, or concerns are going through your mind about the program that is described? In general, does the (advertisement/flyer) describe something that you would be interested in? Why or why not? What would make you decide to respond (or not respond) to an advertisement like this?

The second part of the interview focused on the factors that would influence the participant's decision to commit to attending the caregiver education program or not, based on the content of the advertising, if the opportunity to participate was available. Sample questions included the following: What would lead you to participate in a caregiver education program? Under what circumstances would you commit the required time to participate? What general factors in your life would prevent or make it difficult for you to participate in a caregiver education program? In addition to these open-ended questions, basic descriptive data were collected so that participants could be described. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed with the participant's permission.

Analysis

All three of the authors read a sample of the transcripts to identify recurrent concepts using a constant-comparative approach.24 Each transcript was read by at least two of the three authors during this open coding process. The authors met three times to achieve consensus about recurrent concepts, and to determine labels and definitions for these concepts. After each meeting, the authors recoded the transcripts using the newly agreed-upon labels and definitions. The authors coded a different set of transcripts after each meeting to ensure that each author had an in-depth understanding of all of the data. Once consensus was established, the authors reread the transcripts a final time to code the transcripts using the established labels and definitions. The third author then reviewed these final coded documents to extract rich quotes that exemplified each of the major concepts.

Results

Five females and two males participated in the interviews. Their ages ranged from 27 to 71 years. The two male participants were both spouses of an individual with MS, whereas the females were either a parent (n = 2), adult child (n = 1), sibling (n = 1), or friend (n = 1) of a person with MS. The participants had known the care recipient between 10 and 49 years, and had been providing assistance for 5 to 10 years. As a group, the participants were well educated—three had master's degrees, two had bachelor's degrees, and one had a high school education. Four of the participants were retired, two were working full time, and one was not working outside the home.

The participants provided rich insights related to the research questions. In terms of the first research question, several aspects of the caregiver study recruitment materials encouraged individuals to seek more information about participation. These aspects included the personal relevance of the program, especially in relation to “triggering events” in their lives, as well as the logistical issues associated with their potential participation. In contrast, other aspects of the caregiver study recruitment materials discouraged individuals from seeking more information about participation. These aspects included the fact that the program was part of a research study, insufficient detail and clarity in the materials to enable determination of the personal relevance and what participation entailed, and possible logistical barriers such as location, transportation, or the inability to leave the person with MS alone while the caregiver attended the program. Specific to the second research question, MS caregivers had several recommendations for improving study recruitment materials. These included enhancement of personally relevant messages, use of language that emphasized that the program would help them manage their specific caregiving situations, use of incentives to encourage participation, and general recommendations about visual design such as using color or glossy paper.

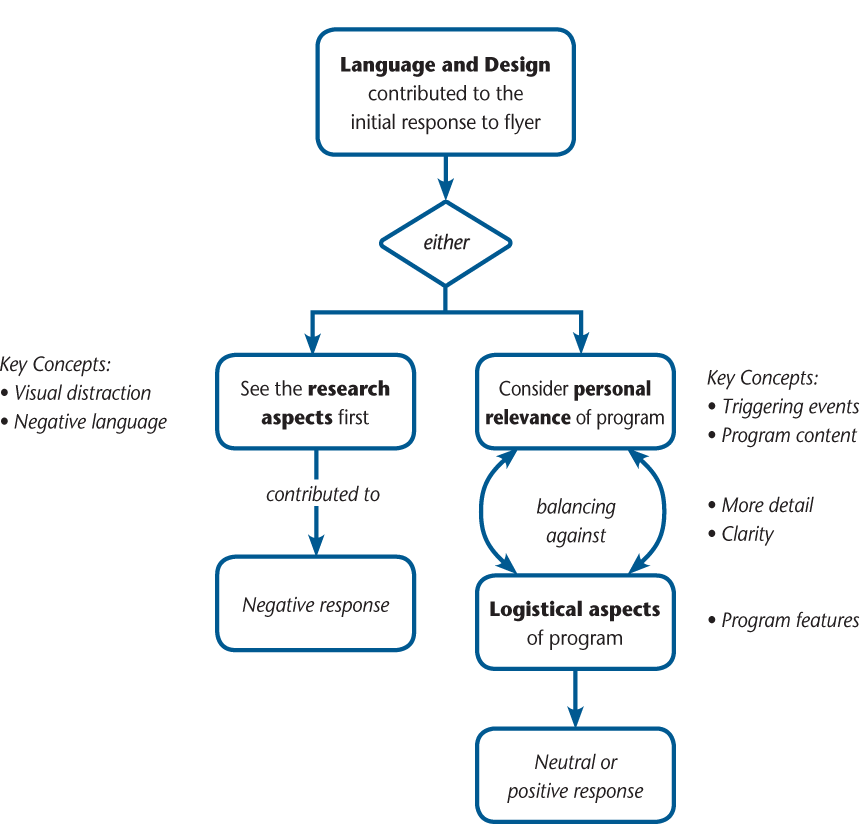

We organized the data into seven key concepts that were reflected in the participants' responses to the three advertisements: visual distraction, negative language, triggering events, program content, amount of detail, clarity, and program features. These concepts were then further organized in relation to each other through one major overarching theme (language and design) and three subthemes (research aspects, personal relevance, and logistical aspects). Figure 1 illustrates the relations among these themes and the key concepts.

Graphic depiction of the study findings

The findings indicated that the language and visual design of the recruitment materials contributed to one of two initial responses by the participants. They either responded first to the research aspects of the materials (n = 3) or considered the personal relevance of the caregiver program described in the materials (n = 4). While all participants eventually addressed both the research aspects and the personal relevance of the program, their initial reaction influenced the remainder of their interviews and their recommendations for improving the materials. In the sections below, the numbers in parentheses following each quote indicate the specific participant (eg, P6 refers to Participant 6) and the line numbers of the transcribed interview (eg, 127–130).

Language and Design

Response 1: Seeing the Research Aspects First

Three participants focused initially on the research aspects of the recruitment materials. The responses of these participants were consistently negative—that is, they indicated that the materials discouraged them from contacting the study office for further information. Nevertheless, all seven participants at some point raised concerns about research-related language in the recruitment materials. Participants homed in on language and design aspects of the flyers that left them with questions about whether participating in the research would result in any personal benefit.

For example, one participant stated, “It kinda sounds like it's a test and [I'm] a guinea pig” (P6, 142–144), indicating that he perceived participation in the caregiver program study as more of an experiment than an opportunity for potential benefit to him. The participants expressed doubts that their participation would be worthwhile. They were hesitant to be part of a study and wanted to be assured of some level of reciprocity. For example, one participant suggested, “I would be wary of use of the word ‘study’ [on the recruitment flyer] because maybe people don't feel like they want to be looked at. If you've got something for me, I'll take it. But [if] I'm giving something to you only, I don't have time for that. ‘Cause I'm a caregiver of someone who is suffering” (P4, 334–337). These doubts about potential reciprocity reduced interest in participating in the study. When sharing how the language on the flyer would influence her interest in participation, another participant said, “the fact that it says it's being tested . . . that might, dissuade me” (P3, 112–114). None of the participants expressed a willingness to participate in research for the broader benefit of MS caregivers in general. Instead, they focused exclusively on their own situations as they reviewed and responded to the materials.

Response 2: Seeing Personal Relevance First

When participants' initial response to the recruitment materials was focused on the personal relevance of the program instead, their comments and questions reflected that they were considering the potential utility of the program. These participants had neutral-to-positive overall responses to the study advertisements. As they discussed the personal relevance of the program, it became apparent that they were contemplating whether the program would provide enough personal benefit to make volunteering for the study worthwhile. In other words, they were actively weighing the individual costs and logistical aspects of participating in a research study (eg, arranging travel, committing time and effort, finding respite) against the potential benefits of the knowledge and skills they might gain.

Some of the participants considered triggering events in their lives and the relevance of the program content and features for their needs given those triggering events. For example, one participant explained, “My first reaction when my daughter was diagnosed was . . . I've got to do something” (P5, 55–56). So, for her, the time when her daughter was newly diagnosed was a time when she might have been motivated to participate in a study involving a caregiver education program. Another participant also thought that early in the disease process would be a time when she would be motivated to participate: “I think it depends on how long the person's had it [MS]. Some people have had it for 20 years. It's a little late in the game. Someone who has had it for 6 months or a year or two—now that's a whole different story” (P2, 291–294). Another participant mentioned that a change in housing could be a trigger for motivation to participate: “I don't actually live with my dad. So . . . if I was planning for my parents to move in with me, then I'd be interested in it” (P3, 158–160).

Some participants wanted more detail and clarity to help determine the personal relevance of the caregiver program and to better understand what participation in the study would entail. The desire to know more about the program is illustrated in a quote from Participant 5, who stated: “I think people like to know exactly what they're getting into” (P5, 89). These participants also wanted to know more about the specific program content and features: “That's why . . . it's good to put meat about what it's looking at—trying to help you enhance your skills . . .” (P3, 214–216). Participant 3 shared that “if it's not really hitting an exact problem that I'm experiencing, that might hinder me from calling” (P3, 11–13). To determine the personal relevance, what participants essentially wanted to know was “Is it going to be useful? Am I actually going to come out of this being helped in some way . . . ?” (P3, 208).

As they considered the personal relevance, the caregivers balanced that relevance against the logistical aspects of participation. For some, transportation and location were important considerations, as illustrated by Participant 2: “Where it's located. If someone's got to drive from the Southside if it's downtown, they're not going to do that” (P2, 338–340). Another participant considered the time commitment: “I would be a little bit concerned with a class every week for 5 weeks . . . that would probably be difficult. And it would definitely be difficult with my schedule, and I think it would be difficult with a lot of people's schedules” (P3, 65–68).

Others felt that participation would be difficult or impossible because it would interfere with caregiving responsibilities. For Participant 5, participation would have been dependent on the time of day at which the program was offered: “I would never have shown up in the evenings because that's when she needed me a lot of the time” (P5, 435–436). Participant 1 considered the monetary cost of respite: “I wouldn't want to drive down because that means finding caregiving for my wife . . . I mean that could be 200 bucks a day” (P1, 375–376).

Recommendations to Improve the Recruitment Materials

Throughout the interviews, the participants offered suggestions to improve the recruitment materials. Participants who first responded to the research aspects of the flyers had specific recommendations for the language used in future recruitment materials. For example, one participant suggested, “Instead of saying ‘you may be eligible to participate’ . . . say something like ‘you should consider’ or ‘please consider’” (P4, 334–337). This same participant also recommended to “be a little more sales oriented . . . a little more active and a little more punchy . . . it's almost like it's written by lawyers, you know?” (P6, 14–17).

Across all interviews, the recommendations focused on enhancing the personally relevant messages. For example, rather than using the term caregiver, participants suggested describing their role as providing “support” or “assistance” to a person with MS, and using terms such as family and/or friend. Participant 3 said, “I like that you just say ‘do you provide support or assistance?’ ‘Cause I think a lot of people wouldn't necessarily . . . consider themselves caregivers” (P3, 8–9). The participants also recommended using wording and language that emphasized that the program would help them manage their caregiving situations: “I think that it's good to put [in the flyer that the program is] trying to help you enhance your skills” (P3, 214–216). And others recommended adding information demonstrating that others had benefited from their participation: “Maybe [include] quotes from other caregivers that have gone through [the study program], especially for things they have dealt with, like maybe anger level” (P3, 127–130).

Some caregivers suggested the use of incentives to encourage participation. For example, one participant said, “People like incentives . . . maybe a grocery store gift certificate, or . . . Walgreens or Target, ‘cause people probably buy a lot of supplies especially if they're caring for somebody” (P3, 291–292, 296–299). Another participant suggested mentioning on the flyer that the program was provided by a professional, and that it was offered free of cost: “. . . ‘you may be able to participate in this free program taught by a licensed OT [occupational therapist].’ See, I think it's important that they know—hey—that it's free and it's also taught by a pro” (P1, 226–228).

Finally, several participants provided general recommendations about how to draw people to the materials. Several of these comments were about the visual design. For example, one participant said, “It needs a little spice in the design . . . if you're walking into a grocery store, say you are putting it up at the Jewel, nobody is going to read this” (P4, 299–301). They had specific suggestions about how to improve the design, such as using color or higher-quality paper: “I think the color helps because it would draw your eye a little more than just another piece of white paper” (P6, 437–439); “I think sometimes glossy paper . . . makes it seem a little more credible or high tech or just mainstream” (P3, 459–462).

Discussion

Little is known about why people participate in studies,21 and there is a paucity of research that reports recruitment outcomes and advice, which can contribute to continued recruitment problems.25 This study helps address this gap for a group that is particularly difficult to recruit: caregivers. The purposes of this study were to explore MS caregivers' reactions to recruitment materials, understand how these reactions influence the decision to seek more information about participation in a research study, and identify caregivers' recommendations for improving recruitment advertising. Although several studies have tested the efficacy and effectiveness of caregiver education programs for care recipients with a variety of diagnoses, recruitment of caregivers for these programs is often challenging.19–21 The results of this study suggest possible strategies to maximize the success of recruitment efforts for future caregiver program studies, and also provide insight into factors that encourage or discourage MS caregivers from seeking more information about participation in a caregiver program research study.

One recommended strategy, based on our findings, is to pilot test recruitment materials before actively recruiting participants. The MS caregivers in this study shared reactions to the recruitment materials that the researchers had not previously considered. Had this information been available before the recruitment phase of the pilot study of the caregiver education program, the materials would have looked different in terms of the language used and the visual design. Furthermore, the caregivers in our study had two distinct initial reactions to the language and design of the materials: either they focused on the research first or they considered the personal relevance of the caregiver program. This difference in initial reactions suggests that no single version of the recruitment materials was best, and different flyer options may be needed in order to attract different audiences. When pilot testing materials, it may be beneficial to involve marketing or advertising staff, especially for larger studies in which such consultative services can be built into the research budget. Researchers for smaller studies could consider liaising with colleges or universities to work with students who need practical marketing and advertising experience. In addition to pilot testing recruitment materials, or if pilot testing is not feasible, we recommend a review of the literature on recruitment of the specific target population to better anticipate and prevent possible recruitment and retention problems.

The results also underscore the importance of timeliness of recruitment. Several of the caregivers interviewed for this study identified a “window of recruitment opportunity”—that is, a specific time when participating in a caregiver educational program would be more relevant because of some kind of triggering event (eg, being newly diagnosed, an exacerbation of illness, or a hospitalization). This finding is similar to a finding by Murphy et al.21 that caregivers of people with dementia were willing to participate in a study at a time when they felt they needed the most help and were accepting of that help. Although timeliness may be an important factor for caregivers of people with a variety of diagnoses, triggering events vary depending on the nature and course of the particular diagnosis of the care recipients (eg, whether it is progressive, has exacerbations and remissions, etc.), and the nuances of specific diseases may suggest times to offer educational programming to caregivers. For example, our results revealed that an MS caregiver educational program might be particularly beneficial following a hospitalization. Therefore, we recommend that researchers and program planners thoughtfully and creatively consider the timing of caregiver program offerings. These programs could, for example, be offered shortly after a hospitalization or during a time when the caregiver may have more time and worry less about being away from the person with MS. These times may be during outpatient medical or therapy visits. Finally, it is also beneficial for researchers to think broadly about the potential benefits of the program being offered in a study, while simultaneously being specific enough about the program so that it seems relevant and worthwhile to participants. Pilot testing materials through individual interviews or focus groups is a way to achieve this balance.

Recruitment strategies are described in the literature as “active” or “passive.”26 Active recruitment strategies involve actively targeting specific individuals or groups, while passive recruitment refers to making a target population aware of the study and allowing interested individuals to contact the researcher. When attempting to recruit caregivers for research, active recruitment approaches can be difficult because researchers rarely have direct access to caregivers. Therefore, passive recruitment approaches are often used. Based on our experience and findings, we recommend pilot testing materials used for passive recruitment. By pilot testing these materials, researchers can better understand the responses of individuals in the target population and modify materials to best meet the needs of the specific population.

A particularly interesting and unexpected finding was the strong reaction of some participants to the research aspects of the recruitment materials. When developing study recruitment materials, researchers must meet the needs of two different audiences simultaneously: the institutional review board and potential participants. Researchers aim to create recruitment materials that are consistent with ethical practices and transparent about the research aspects of the studies. Yet several of our caregiver participants expressed that such language would likely deter them from participation. Therefore, close collaboration with the institutional review board to pilot test different versions of recruitment materials that are appealing to potential participants and compliant with research policies and procedures may be required.

Finally, altruism has been found to be a motivator for participation in studies for people with a variety of conditions including human immunodeficiency virus infection,27 cancer,28 schizophrenia,29 and lupus.30 It is not clear, however, if caregivers choose to participate in research studies for altruistic reasons. When our participants were asked about factors that would influence their decision to participate in a caregiver study, none mentioned interest in participating for the broader benefit of caregivers; however, Murphy et al.21 found that one way caregivers of people with dementia justified their participation in a research study was through realizing that they were contributing to caregiver research. It may be that caring for a person with MS and caring for a person with dementia are different, resulting in different motivators to participate in a research study. Some authors have suggested that it may be possible to increase interest in research study participation by explicitly emphasizing the altruistic reasons for participation in a study and helping potential participants understand the purpose and importance of the study.31–33 These studies, however, involved people with medical conditions; therefore, further investigation would need to be done to determine whether emphasizing altruistic reasons and the purpose of the study could improve the recruitment of caregivers.

This study was limited by small sample size that did not capture the full diversity of potential MS caregivers. More caregivers may have resulted in greater diversity and different responses to the study advertisement. Also, although the interview questions were consistent, two methods of interviewing were used: in-person interviews and telephone interviews. These different methods may have influenced the results. Those caregivers who participated in telephone interviews had the study advertisements prior to the interview. If they reviewed them in advance of the interview, they may have developed opinions about them in advance. The caregivers who participated in person were shown the advertisements for the first time during the interview and thus provided only their initial reactions.

Conclusion

Caregiving is a challenging role that can have negative effects on the caregiver. While it is important to determine the efficacy and effectiveness of caregiver education programs, researchers frequently report that it is difficult to recruit caregivers for studies. In this study, we explored MS caregivers' reactions to research advertisements, reactions that influenced seeking more information about participation in a caregiver education research study, and recommendations for improving recruitment advertising. The participants in our study either responded first to the research aspects of the recruitment materials and had overall negative responses to the materials or first considered the personal relevance of the caregiver program being tested and had neutral-to-positive responses. They also offered many recommendations for changes to the recruitment materials that we had not previously considered. While recruiting for caregiver education research can be challenging, piloting recruitment materials and using a variety of advertising options may help improve recruitment success.

PracticePoints

Research is needed to determine the effectiveness of MS caregiver education programs, but recruitment for such studies can be difficult.

The wording and visual design of recruitment materials, as well as the timing of recruitment, can influence potential study participants' initial responses to such materials.

Researchers may be able to improve recruitment response by pilot testing recruitment materials and developing different versions to target specific audiences.

References

Norburn JE, Bernard SL, Konrad TR, et al. Self-care and assistance from others in coping with functional status limitations among a national sample of older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995; 50: S101–109.

Wiles J. Daily geographies of caregivers: mobility, routine, scale. Soc Sci Med. 2003; 57: 1307–1325.

Barker JC. Neighbors, friends, and other nonkin caregivers of community-living dependent elders. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002; 57B: S158–167.

Carton H, Loos R, Pacolet J, Versieck K, Vlietinck R. A quantitative study of unpaid caregivers in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2000; 6: 274–279.

Cheung J, Hocking P. The experience of spousal carers of people with multiple sclerosis. Qualitat Health Res. 2004; 14: 153–166.

McKeown LP, Porter-Armstrong AP, Baxter GD. The needs and experiences of caregivers of individuals with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2003; 17: 234–248.

O'Hara L, De Souza L, Ide L. The nature of care giving in a community sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2004; 26: 1401–1410.

Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH, Gould DA, Levine C, Kuerbis AN, Donelan K. When the caregiver needs care: the plight of vulnerable caregivers. Am J Public Health. 2002; 92: 409–413.

Teel CS, Leenerts MH. Developing and testing a self-care intervention for older adults in caregiving roles. Nurs Res. 2005; 54: 193–201.

Given BA, Given CW. Health promotion for family caregivers of chronically ill elders. Ann Rev Nurs Res. 1998; 16: 197–217.

Fung W, Chien W. The effectiveness of a mutual support group for family caregivers of a relative with dementia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2002; 16: 134–144.

Hartke R, King R. Head trauma and stroke: the effectiveness of a telephone support group for stroke caregivers. Rehabil R&D Progr Rep. 1997; 34: 124–125.

Mason A, Weatherly H, Spilsbury K, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of respite for caregivers of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007; 55: 290–299.

Chen M. The effectiveness of health promotion counseling to family caregivers. Public Health Nurs. 1999; 16: 125–132.

Gallagher EM, Hagen B. Outcome evaluation of a group education and support program for family caregivers. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 1996; 17: 33–50.

Farran CJ, Loukissa D, Perraud S, Paun O. Alzheimer's disease caregiving information and skills. Part II: family caregiver issues and concerns. Res Nurs Health. 2004; 27: 40–51.

Hepburn KW, Tornatore J, Center B, Ostwald SW. Dementia family caregiver training: affecting beliefs about caregiving and caregiver outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001; 49: 450–457.

Bucher JA, Loscalzo M, Zabora J, Houts PS, Hooker C, BrintzenhofeSzoc K. Problem-solving cancer care education for patients and caregivers. Cancer Pract. 2001; 9: 66–70.

Barg FK, Pasacreta JV, Nuamah IF, et al. A description of a psychoeducational intervention for family caregivers of cancer patients. J Fam Nurs. 1998; 4: 394–413.

Franzen-Dahlin A, Larson J, Murray V, Wredling R, Billing E. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of a support and education programme for spouses of people affected by stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2008; 22: 722–730.

Murphy MR, Escamilla MI, Blackwell PH, et al. Assessment of caregivers' willingness to participate in an intervention research study. Res Nurs Health. 2007; 30: 347–355.

Finlayson M, Preissner K, Garcia J. Pilot study of an educational programme for caregivers of people ageing with multiple sclerosis. Br J Occup Ther. 2009; 72: 11–19.

Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A “How To” Guide 1999: http://fog.its.uiowa.edu/~c07b209/interview.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2011.

Glaser BG. The constant comparative method. Soc Problems. 1965; 12: 436–445.

Tarlow BA, Mahoney DF. The cost of recruiting Alzheimer's disease caregivers for research. J Aging Health. 2000; 12: 490–510.

Lee RE, McGinnis KA, Sallis JF, Castro CM, Chen AH, Hickmann SA. Active vs. passive methods of recruiting ethnic minority women to a health promotion program. Ann Behav Med. 1997; 19: 378–384.

Balfour L, Corace K, Tasca GA, Tremblay C, Routy J-P, Angel JB. Altruism motivates participation in a therapeutic HIV vaccine trial (CTN 173). AIDS Care. Nov 2010; 22: 1403–1409.

Ellis E, Riegel B, Hamon M, Carlson B, Jimenez S, Parkington S. The challenges of conducting clinical research: one research team's experiences. Clin Nurse Spec. 2001; 15: 286–294.

Roberts LW, Green Hammond KA, Geppert CM. Perspectives on medical research involving men in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006; 32: 360–365.

Costenbader KH, Brome D, Blanch D, Gall V, Karlson E, Liang MH. Factors determining participation in prevention trials among systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a qualitative study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007; 57: 49–55.

Aitken L, Gallagher R, Madronio C. Principles of recruitment and retention in clinical trials. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003; 9: 338–346.

Grant JS, DePew DD. Recruiting and retaining research participants for a clinical intervention study. J Neurosci Nurs. 1999; 31: 357–362.

Levkoff S, Sanchez H. Lessons learned about minority recruitment and retention from the Centers on Minority Aging and Health Promotion. Gerontologist. 2003; 43: 18–26.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported in part by a pilot research grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.