Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Case Report: Scrambler Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Central Neuropathic Pain in a Patient with Transverse Myelitis

Author(s):

Abstract

Central neuropathic pain is a severely disabling consequence of conditions that cause tissue damage in the central nervous system. It is often refractory to treatments commonly used for peripheral neuropathy. Scrambler therapy is an emerging noninvasive pain-modifying technique that uses transcutaneous electrical stimulation of nociceptive fibers with the intent of reorganizing maladaptive signaling pathways. It has been examined for the treatment of peripheral neuropathy with favorable safety and efficacy outcomes, but its application to central neuropathic pain has not been reported in transverse myelitis. We describe the use of Scrambler therapy in a patient with persistent central neuropathic pain due to transverse myelitis. The patient had tried multiple drugs for treatment of the pain, but they were not effective or caused adverse effects. After a course of Scrambler therapy, pain scores improved considerably more than what was reported with previous pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. This case supports further investigation of Scrambler therapy in multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, and other immune-mediated disorders that damage the central nervous system.

Transverse myelitis (TM) is a rare immune-mediated neurologic condition characterized by inflammation in the spinal cord. It can be monophasic and idiopathic in nature or caused by relapsing immunologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis (MS), neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), or systemic autoimmune diseases.1 Spinal cord damage in TM can result in a spectrum of neurologic dysfunction, including weakness, loss of sensation, urinary and/or bowel dysfunction, and neuropathic pain.1 Neuropathic pain is characterized by a burning, shooting, or tingling sensation in the face, arms, torso, and/or legs and is associated with worse health than is nonneuropathic pain.2 It is particularly difficult to treat, with only 40% to 60% of those with neuropathic pain achieving even partial relief, especially when it is central in origin.3 Currently, there is no standard of care for central neuropathic pain treatment, and off-label use of medications typically used for peripheral neuropathy are often insufficient or cause intolerable adverse effects such as fatigue.3–5

Herein we describe the use of Scrambler therapy for central neuropathic pain treatment in a patient with TM. Scrambler therapy is a novel noninvasive neuromodulatory technology that uses transcutaneous electrical stimulation of ascending C-fibers through surface electrodes with the intent of reorganizing maladaptive signaling pathways.6 It has been examined for the treatment of peripheral neuropathy with favorable outcomes,7 but little is known about its potential application in central neuropathic pain.

Case Presentation

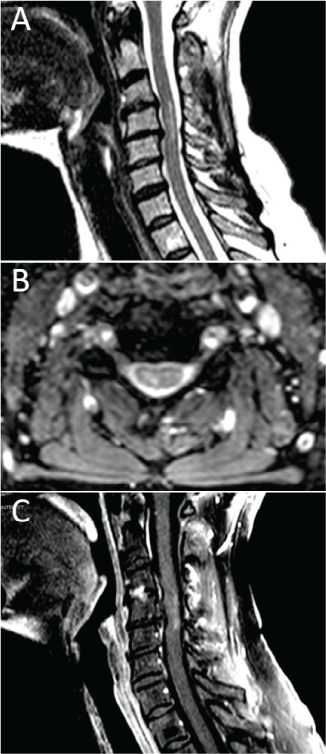

A 65-year-old white woman with a history of TM presented with long-standing central neuropathic pain. She was initially evaluated at an outside hospital in October 2013 for right hand paresthesia with accompanying neck pain followed by lower extremity weakness, right arm incoordination and weakness, urinary retention, torso band-like tightness, and impaired ambulation. Progression to nadir developed over approximately 24 hours. Neuroaxial imaging showed a C3-5 lesion on T2-weighted sagittal and axial sequences, with mild ill-defined peripheral enhancement on postgadolinium T1-weighted sequences (Figure 1). Mild foraminal stenosis was noted, although flexion/extension radiographs indicated preserved cerebrospinal fluid signal surrounding the cord. No flow voids were noted. Given the magnetic resonance imaging findings in the setting of symptoms attributable to the described lesion, the presence of a sensory level, progression to nadir between 4 hours and 21 days, the presence of oligoclonal bands, and a thorough autoimmune evaluation to rule out other causes, the diagnosis of TM was made in concordance with the 2002 TM diagnostic criteria.8 Muscle and nerve conduction studies were performed, and the results were unremarkable. The patient underwent 5 days of high-dose corticosteroid therapy and had modest improvement in her neurologic status.

Magnetic resonance imaging showing a C3-5 lesion after presentation of symptoms

The patient presented to the Johns Hopkins Transverse Myelitis Center in April 2014 for a second opinion regarding her persistent weakness and severe neuropathic pain. Neurologic examination demonstrated diffuse hyperreflexia, mild left hip flexion weakness, and gait dysfunction. In-depth interview revealed that her neuropathic pain (in her bilateral legs, right arm, and torso) was the most disabling aspect of her condition. She was taking hydrocodone-acetaminophen (5–300 mg every 6 hours as needed) and tramadol (50 mg every 4 hours as needed) before presenting to us, which was only partially beneficial. She subsequently tried several other therapies that were ineffective, were only partially helpful, or caused intolerable adverse effects, including duloxetine (120 mg daily), gabapentin (900 mg three times daily), pregabalin (50 mg twice daily), nortriptyline (50 mg daily), capsaicin, topical lidocaine, meditation, and acupuncture. In early 2017 she was offered Scrambler therapy for refractory pain treatment. At the time of Scrambler treatment she was taking duloxetine (120 mg) daily and topical lidocaine as needed. The patient received Scrambler therapy for 45 minutes daily for 10 consecutive weekdays, the typical administration as for other types of pain.9 Before initiation of Scrambler treatment the patient reported a morning pain level of 5 of 10 using an 11-point (0–10) numeric rating scale (NRS), which would increase to an NRS pain level of 10 of 10 by nighttime, as well as with exertion and stress. She had developed activity intolerance secondary to pain. The neuropathic pain was located in the regions mentioned previously herein, and she reported severe allodynia in her right upper extremity that interfered with her grip. Moreover, the pain interfered with her sleep.

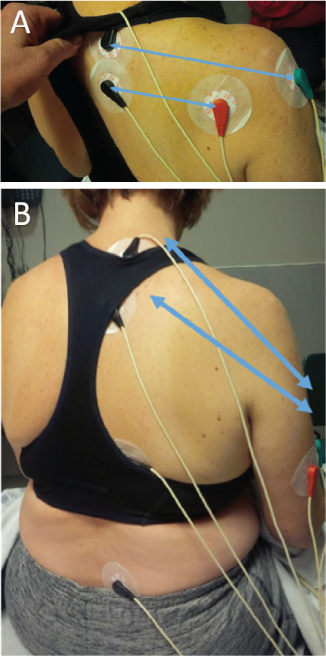

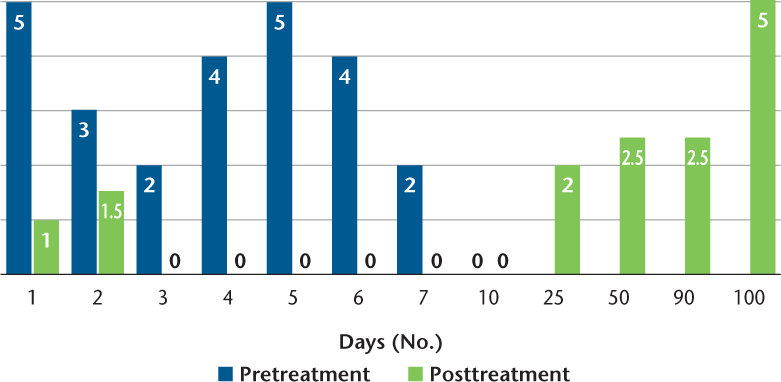

The stated purpose of Scrambler therapy is to provide “nonpain” information to replace continued pain-generation impulses.7 To do this requires capturing the surface receptors of the C-fibers (and perhaps other fibers) in the dermatome of the affected nerves. The placement is performed to also avoid putting an electrode directly on an area of damaged nerve sensation. This patient's worst pain was in the C6, C7, C8 distribution and involved the distal arm to the axilla; she also had pain in the T1, L5 distribution. To begin, we placed sets of electrodes (“channels”) in the C6 and C8 dermatomes in an area of normal sensation, approximately 8 inches apart, being careful to stay above the area of distal allodynia and pain (Figure 2). At the end of day 1 treatment her NRS pain score decreased to 1 of 10 and her allodynia was improved. By day 2, the pain had returned to 3 of 10, but the pain/allodynia area had moved down the arm such that we could treat with pairs of electrodes on C6, C7, and T8 with the distal lead on the medial arm for C8, and L5 to L5. At the end of day 2 treatment the NRS pain score decreased to 1.5 of 10, with resolution of banding sensation and shoulder and upper arm pain. On day 3 her pain score started at 2 of 10. All five channel pairs of electrodes were used, each spanning across one of the following dermatomes: C6, C7, C8, T8, and L5. The patient continued with all five channel pairs for the duration of treatment. Before beginning treatment on day 4, her NRS pain score was reported to be 4 of 10, and by the end of treatment it was 0 of 10; of note, allodynia had completely resolved. Her pain continued to decline in severity and in location daily after each treatment, with the pain being nearly resolved by the end of day 10 (Figure 3). The patient reported no adverse events.

Electrode placement for the patient's Scrambler therapy

Numeric rating scale pain scores daily pretreatment and posttreatment and at indicated follow-up intervals

In the 30 days after Scrambler intervention, the patient's pain remained improved, with a pain score of 2.5 of 10. Furthermore, her sleep and activity intolerance improved. During 90-day follow-up, her pain began to increase to pretreatment levels. However, the patient reported that Scrambler therapy helped in reducing her pain more than any previous therapy, and she expressed a desire to receive another course of treatment.

Discussion

Scrambler therapy is a noninvasive technology approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in February 2009 for treating acute, chronic, and postoperative pain.9 Scrambler therapy uses peripheral nerve stimulation to modify ascending sensory responses in the spinal cord. The theory behind Scrambler treatment is that “scrambled” waveforms are dynamically assembled into strings of information that are interpreted by the brain to replace pain with “no-pain” information.6 7 The waveform is constantly changing, with 16 different patterns that look like action potentials, which differentiates it from the on/off pattern of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Scrambler therapy has been examined in conditions that cause peripheral nerve damage, including chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and postsurgical neuropathic pain, with favorable results.6 7 In central neuropathic pain, the damaged neurologic circuits reside in the spinal cord rather than in the peripheral nerve. The stimulation to dermatomes corresponds to intact spinal cord tissue such that ascending sensory responses in the spinal cord may be modified. This is supported by data using another type of peripheral nerve stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, which suggests that peripheral nerve stimulation activates central mechanisms to produce analgesia.10 Studies have not reported the use of Scrambler therapy in conditions that cause central neuropathic pain except a single case report involving a patient with a 12-year history of central pain after a medullary cavernoma bleed who noted a reduction in pain from 9–10 of 10 to 0–0.5 of 10 after treatment.11 Specifically, to our knowledge this is the first report of Scrambler therapy use in a demyelinating disease despite the high burden of pain in patients with TM, MS, and NMOSD. In MS, 29% to 86% of patients report neuropathic pain, which affects quality of life.12 Magnetic resonance imaging studies support the hypothesis that central neuropathic pain triggered by MS is more common in those with myelopathic lesions.12 As such, it is not surprising that the burden and prevalence of pain are even greater in patients with severe spinal cord damage from NMOSD, with 62% to 91%reporting its presence; research reveals that its pervasiveness affects mood, mobility, and quality of life.4 5 13 14

The present patient experienced persistent central neuropathic pain for 3.5 years before Scrambler therapy and reported that this treatment improved her pain considerably more than previous pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. The patient further recounted that this treatment was tolerable, and no safety concerns have emerged in this patient or others treated with Scrambler.7 The present patient's reemergence of pain at approximately 90 days mirrors data from Scrambler therapy use in peripheral neuropathic pain conditions. Observational research suggests that patients who receive subsequent treatments continue to respond to additional treatments, often with fewer treatments needed over time.15 16 Scrambler therapy is an emerging noninvasive treatment that may be safe and effective for central neuropathic pain. Notably, most reports of Scrambler therapy use have been observational, in which the impact of the placebo effect could not be accounted for, including in the present report. Nonetheless, this open-label case report supports comprehensive, well-controlled investigation of Scrambler therapy in MS, NMOSD, and other disorders that cause refractory central neuropathic pain.

PRACTICE POINTS

Central neuropathic pain is a severely disabling component of immune-mediated diseases that affect the central nervous system.

Scrambler therapy is an emerging noninvasive pain-modifying technique that has been used for peripheral neuropathic pain.

The use of Scrambler therapy for central neuropathic pain in a patient with transverse myelitis is described.

Acknowledgments

Ms. Mealy is a PhD candidate at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. The patient provided written permission to share her story and photographs for educational purposes.

References

Greenberg BM, Frohman EM. Immune-mediated myelopathies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21:121–131.

Cohen SP, Mao J. Neuropathic pain: mechanisms and their clinical implications. BMJ. 2014;348:f7656.

Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132:237–251.

Qian P, Lancia S, Alvarez E, Klawiter EC, Cross AH, Naismith RT. Association of neuromyelitis optica with severe and intractable pain. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1482–1487.

Pellkofer HL, Havla J, Hauer D, et al. The major brain endocannabinoid 2-AG controls neuropathic pain and mechanical hyperalgesia in patients with neuromyelitis optica. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71500.

Coyne PJ, Wan W, Dodson P, Swainey C, Smith TJ. A trial of Scrambler therapy in the treatment of cancer pain syndromes and chronic chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2013;27:359–364.

Majithia N, Smith TJ, Coyne PJ, et al. Scrambler Therapy for the management of chronic pain. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2807–2814.

Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group. Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology. 2002;59:499–505.

Food and Drug Administration. 501(k) summary for the Competitive Technologies, Inc. Scrambler Therapy MC-5A TENS device. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf8/K081255.pdf. Published February 20, 2009. Accessed October 14, 2016.

DeSantana JM, Walsh DM, Vance C, Rakel BA, Sluka KA. Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for treatment of hyperalgesia and pain. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:492–499.

D'Amato SJ, Mealy MA, Erdek MA, Kozachik S, Smith TJ. Scrambler therapy for the treatment of chronic central pain: a case report. AA Pract. 2018;10:313–315.

Nick ST, Roberts C, Billiodeaux S, et al. Multiple sclerosis and pain. Neurol Res. 2012;34:829–841.

Zhao S, Mutch K, Elsone L, Nurmikko T, Jacob A. Neuropathic pain in neuromyelitis optica affects activities of daily living and quality of life. Mult Scler. 2014;20:1658–1661.

Hollinger KR, Franke C, Arenivas A, et al. Cognition, mood, and purpose in life in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. J Neurol Sci. 2016;362:85–90.

Smith T, Cheville AL, Loprinzi CL, Longo-Schoberlein D. Scrambler therapy for the treatment of chronic post-mastectomy pain (cPMP). Cureus. 2017;9:e1378.

Smith TJ, Auwaerter P, Knowlton A, Saylor D, McArthur J. Treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-related peripheral neuropathy with Scrambler Therapy: a case report. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28:202–204.