Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Short Report: Adherence to Neuropsychological Recommendations in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

Background:

Adherence to nonmedication recommendations is typically low, as seen in various health populations. Because literature on adherence to treatment recommendations made after neuropsychological testing in multiple sclerosis (MS) is lacking, this study evaluated adherence and reasons for nonadherence. Relationships between adherence to recommendations and various other factors in patients with MS were also evaluated.

Methods:

Of 66 adult patients seen for neuropsychological testing at an MS center, 55 were eligible for this study. Forty-five patients (mean age, 43.4 years; 75.6% women) were reached by phone, and all agreed to an interview involving questions regarding adherence to treatment recommendations. Other information was obtained through retrospective medical record review.

Results:

Overall self-reported adherence to recommendations made from neuropsychological testing was 38%. Adherence rates varied by recommendation type: psychopharmacological management had the highest rate (80%), and referrals for cognitive rehabilitation had the lowest (6.5%). Reasons for nonadherence included needing more information and wanting to speak with one's physician regarding the recommendations. Adherence was associated with patients' ability to spontaneously recall at least some of their recommendations and with receiving both a written report and a phone call with test results.

Conclusions:

Adherence to recommendations made after neuropsychological testing for patients with MS is low. Points of intervention may be to give directed feedback for each recommendation and to provide both a written report and a phone call with results and recommendations. Asking patients to repeat back the recommendations may be a simple and efficient way to increase understanding and improve adherence.

As many as 70% of people with multiple sclerosis (MS) experience mild-to-severe cognitive deficits, most commonly in processing speed, executive functioning, visual learning, and memory.1 Cognitive impairments affect quality of life2 and employment status3 and are associated with anxiety and depression.4 5 Comprehensive neuropsychological testing can identify areas of cognitive dysfunction and other moderating symptoms, such as fatigue and psychiatric distress.6 7 Most important, neuropsychological testing may yield recommendations for beneficial interventions, such as cognitive remediation, fatigue management, and psychiatric care.8

The MS literature is lacking in adherence rates to recommendations made after neuropsychological testing. Although adherence to medication in patients with MS is adequate (65%–80%),9–11 literature from other populations suggests that adherence to nonmedication recommendations is substantially lower.12–14 Adherence to treatment recommendations is likely beneficial to people with MS as with other populations,15 but data are insufficient. In addition, although the literature indicates that oral feedback is beneficial for patients and improves adherence,16–19 it is unknown whether written and/or oral feedback leads to better adherence to treatment recommendations in people with MS.

To our knowledge, there are no published studies identifying whether people with MS complete recommendations made after neuropsychological testing and what factors prevent adherence. Thus, for people with MS we sought to explore 1) rates of adherence to such recommendations, 2) reasons for nonadherence, and 3) the effect of oral (phone call) and written feedback over written feedback alone. We hypothesized that phone plus written feedback would be associated with higher adherence.

Methods

Participants

Patients included in this retrospective, cross-sectional study received neuropsychological testing as part of routine clinical care at the MS Center of Holy Name Medical Center (Teaneck, NJ) throughout 2015 and 2016. All the patients were fluent English speakers. Eligibility criteria included having MS (as indicated in their medical record) and having received recommendations after neuropsychological testing. Although age was not a specific criterion, no one younger than 18 years was seen for neuropsychological testing in 2015–2016. At least four attempts to contact a patient were made before excluding a patient from the study. Patients were given one to four recommendations, with most receiving three. Data collection took place from January 1 through March 31, 2017.

Procedures

Albert Einstein College of Medicine (Bronx, NY) provided institutional review board approval. Patients were contacted by the study coordinator (M.S.) and by doctoral students in the MS psychology laboratory (S.S., J.G.P., R.A., E.M., J.S., J.B., or L.G.) and were asked standardized closed- and open-ended questions regarding adherence to recommendations from neuropsychological testing via phone. Other information, including demographic variables and neuropsychological functioning, was obtained via retrospective medical record review.

Measures

During the standardized phone interview, patients were asked if they recalled receiving a mailed report and a phone call from the psychologist regarding feedback from testing. These two variables were dichotomized between a “yes” response and those responding “no” or who were unsure. Despite standard procedures to both mail a copy of the report and provide phone feedback to patients, some patients did not receive phone feedback if the psychologist was unable to reach them. In addition, on one occasion, a spouse confirmed that a patient had received phone feedback but was unable to recall it (the patient's report, not the spouse's, was coded). Thus, these variables were coded as “Recalled receiving paper copy of report in the mail” and “Recalled receiving phone feedback of results and recommendations.”

Next, patients were asked what recommendations they recalled. This variable was dichotomized between patients with no recall of any recommendations and those who had spontaneous recall of some or all recommendations. After the interviewer reminded the patient of any forgotten recommendations, the patient was asked which they had completed, why they had not completed the others, and whether they planned to complete them. Reasons for nonadherence were sorted into five categories (post hoc): 1) wanting more information or to speak with their neurologist about the recommendation, 2) difficulty navigating insurance or finding a provider, 3) not thinking the recommendation was necessary, 4) too busy/lack of time, and 5) other.

Finally, patients were asked whether they adhered to their disease-modifying therapy (DMT) or other medications they take regularly. The following options were given for this question: “I take it as prescribed”; “I miss it once in a while”; “I miss it often”; “I never take it”; and “I am not currently taking a DMT or medication regularly.” Responses were dichotomized into “Takes as prescribed” or “Misses it once in a while or more.”

The following measures were used to evaluate neuropsychological functioning, mood, and fatigue at the time of testing. The Minimal Assessment of Cognitive Function in Multiple Sclerosis (MACFIMS) battery is a well-validated neuropsychological measure in people with MS that takes approximately 90 minutes to administer.20 A composite z score was created to include one to two aspects of each domain from this battery (included scores: California Verbal Learning Test, Second Edition [CVLT-II] total immediate recall; CVLT-II delayed free recall; Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–R [BVMTR] total immediate recall; BVMT-R delayed recall; Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System Sorting Test, Free Sorting Description Score, and Sort Recognition Description Score; Symbol Digit Modalities Test; Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test 3-second trial; verbal fluency tests [FAS and animal naming]; and Judgment of Line Orientation). For participants who did not complete one or more MACFIMS tests, composite scores were calculated without those variables.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-921 is a nine-item Likert-type scale measuring depression. Scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 indicate mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.

The Fatigue Severity Scale22 is a nine-item self-report measure of fatigue severity wherein respondents rate their agreement with statements about their fatigue. A score exceeding 44 indicates clinically significant fatigue.23

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, version 23.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Skewness and kurtosis were examined and found acceptably normal for all variables used. Associations between a dichotomized adherence variable and patient descriptive variables (including demographic and patient characteristics) were calculated using independent t tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact χ2 tests for dichotomous or nominal variables (due to the small cell size of several variables24). Adherence descriptive statistics were also calculated.

Results

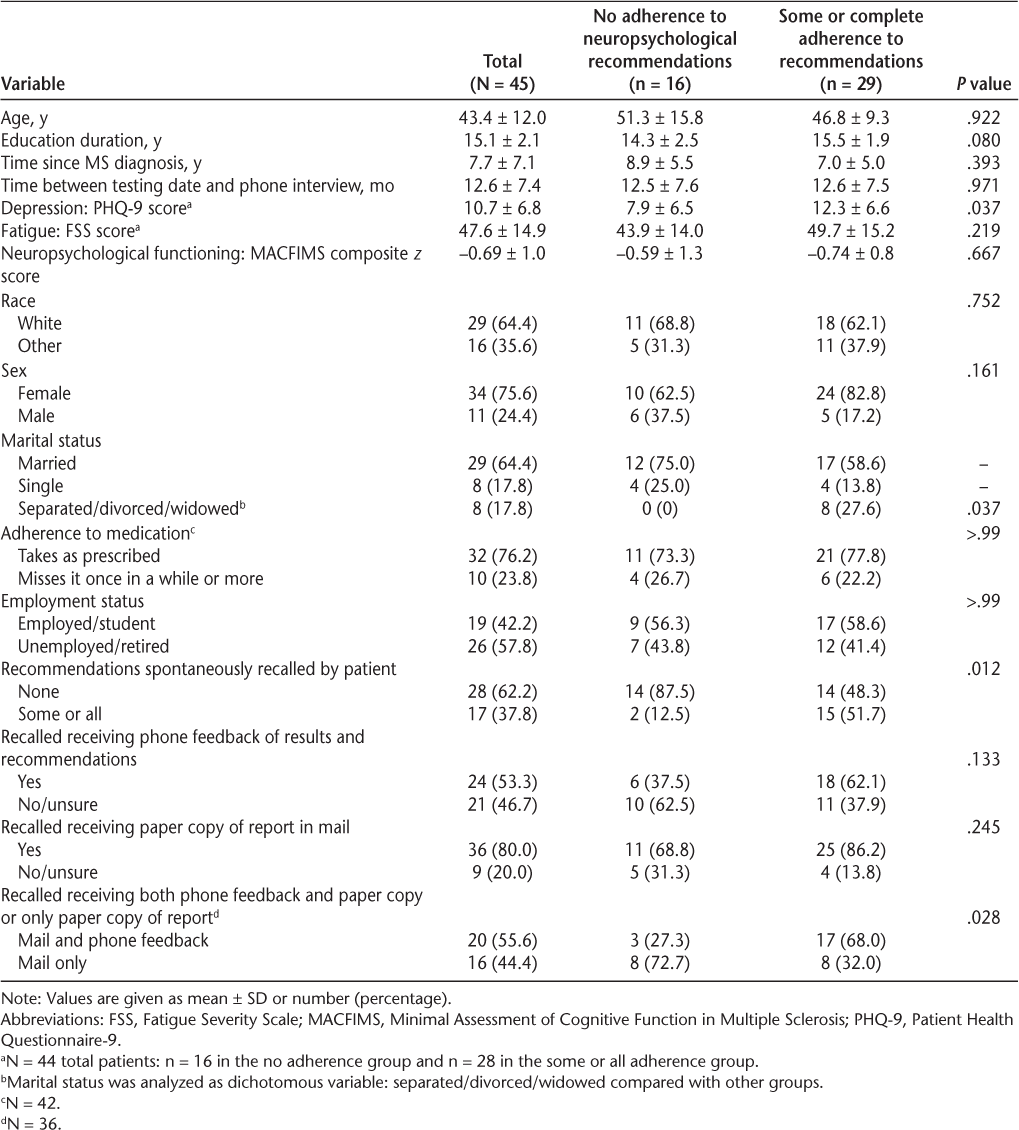

Of the 66 patients seen during 2015 and 2016, eight received no specific recommendations after neuropsychological testing, one did not have MS, one had noninterpretable results, and one was included in another study, making her ineligible; thus, 55 patients were eligible and were contacted by phone. A total of 45 patients with MS (mean [SD] age, 43.4 [12.0] years) were reached and included in this study (Table 1). Women made up 75.6% of the sample, consistent with the higher prevalence of women in the MS population.25 The mean MACFIMS composite score was within the reference range (no significant differences between groups; P = .667). For the 42 patients who reported regular medication/DMT use, 76.2% reported taking their medication as prescribed, while 23.8% reported that they missed their medication “once in a while” or “often.” Table 2 further describes patient characteristics and descriptive statistics.

Patient descriptive statistics

Adherence descriptive statistics

Partial or complete adherence to neuropsychological test recommendations was associated with recalling having received both written and phone feedback rather than only written feedback (P = .028). Partial or complete adherence was also associated with greater depression (P = .037); being separated, divorced, or widowed (P = .037); and spontaneous recall of some or all recommendations (P = .012). No significant relationship was found between neuropsychological functioning and adherence to recommendations (P = .667).

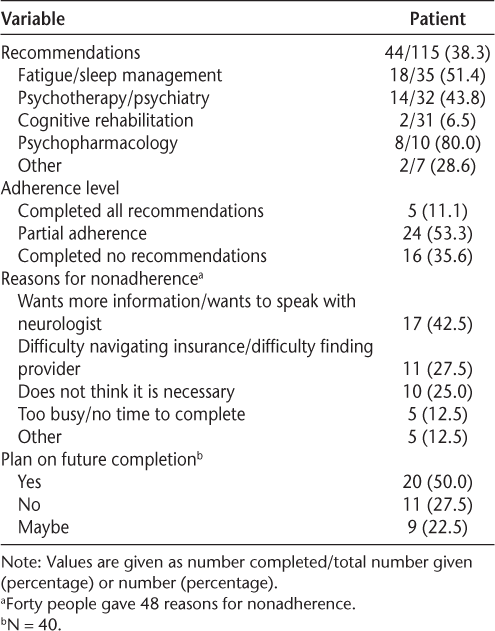

Patients were given one to four recommendations, with most (n = 24 [53%]) receiving three. Overall, this sample of 45 patients with MS received 115 recommendations, of which 44 were reportedly completed, yielding a 38.3% overall adherence rate. Five patients completed all the recommendations (11.1% total adherence), 24 completed some (53.3% partial adherence), and 16 completed none (35.6% nonadherence). Of the 40 patients with no or partial adherence, 20 (50.0%) reported that they planned to complete the recommendations and 9 (22.5%) reported that they might.

Adherence to recommendations that patients follow up with a neurologist or psychiatrist regarding psychopharmacological management of psychiatric symptoms was 80%. Adherence to recommendations for fatigue and sleep management was 51.4%. A general recommendation for psychotherapy or psychiatry referral, without specifying the provider to be used, had adherence of 43.8%. Finally, recommendations for cognitive rehabilitation were followed 6.5% of the time.

Reasons for nonadherence included wanting more information and/or to speak with one's neurologist regarding the recommendation (42.5%), difficulty navigating insurance or finding a provider (27.5%), deciding the recommendation was unnecessary (25.0%), and being too busy or not having time (12.5%). Other reasons for nonadherence were categorized as “other” (12.5%).

Time between neuropsychological testing and the phone interview was 2–25 (median, 11) months. Number of months since testing was unrelated to recommendation adherence (t = −0.037, P = .971) or spontaneous recall of recommendations (t = 1.224, P = .228).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this cross-sectional study is the first to evaluate adherence and reasons for nonadherence to recommendations and referrals made after neuropsychological testing in persons with MS. This study of 45 patients revealed that overall adherence was low. There was, however, significant variation in adherence rates depending on recommendation type. Recommendations for the patient to seek psychopharmacological management from their neurologist or psychiatrist had the highest adherence (notably, this was measured in only 10 patients). Other recommendations were followed less frequently. Referrals for fatigue and sleep management or for general psychotherapy or psychiatry were followed approximately half the time. Patients reported the lowest adherence to cognitive rehabilitation referrals.

Reasons for nonadherence were multifaceted. Most commonly, patients wanted more information or to speak with their neurologist. Although it is not standard practice for neurologists to review neuropsychological test reports with patients, this finding suggests that such a practice may be beneficial. It would also be worth investigating in a future study whether follow-up by the patients' neurologist who endorses the recommendations and facilitates adherence might reduce the disparity between rates of adherence to pharmacological and nonpharmacological recommendations. A large percentage of patients also reported difficulty with logistical aspects of completing a recommendation, such as navigating insurance, finding a provider, or finding the time. This suggests that people with MS require more support than they are currently receiving. Closer monitoring by a clinical case manager/social worker might improve adherence by reminding patients about recommendations and helping them overcome these logistical problems. Finally, one-quarter of the patients reported that they found a recommendation unnecessary, suggesting that psychoeducation and greater discussion of recommendations with either the psychologist or the neurologist is warranted. Notably, more than three-quarters of patients reported that they planned to complete or would consider completing the given recommendations if barriers to completion were removed, suggesting that there is significant room for interventions to improve adherence.

With respect to the hypothesis, when patients recalled having received both a phone call and a mailed report, they were more likely to complete at least some recommendations compared with patients who recalled only a mailed report. This supports the hypothesis, suggesting that providing oral feedback in-person or by phone, in addition to a written report, may be critical to improving adherence. In addition, we found that spontaneous recall of at least some recommendations was associated with treatment adherence (although, notably, the rate of recall for recommendations was only 37.8%). This is in line with other research that one's ability to recall information is associated with better understanding of that information, often due to physician-patient communication that allows the patient to ask questions and understand the importance of recommendations.18 19 Thus, asking the patient to repeat back a recommendation or confirm understanding is likely beneficial.

The present findings also revealed that adherence to at least some of the recommendations was associated with being separated, divorced, or widowed as well as having higher depression. However, depressed patients were likely to receive more recommendations, and, thus, had more opportunity to complete one or more. Also, surprisingly, neither neuropsychological functioning nor employment status was related to treatment adherence in this sample, despite the considerable logistical and motivational barriers presented by both.

A limitation of this study is the small sample size, limiting multivariate analyses and correction for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, this study did not randomize participants to receive a paper copy or a paper copy plus oral (phone) feedback, limiting causal interpretations. Instead, we relied on uncorroborated, retrospective patient self-reporting, which is susceptible to recall bias. In addition, given that the psychologist attempted to contact all the patients, there may be inherent differences between patients who did and did not return the psychologist's phone call. Finally, it is notable that patients in this study received free neuropsychological testing at Holy Name Medical Center. Adherence rates could differ for a population that pays (or has to access payer approval) for the service.

PRACTICE POINTS

Phone interviews with 45 patients with MS were completed to determine whether they had followed the recommendations made after neuropsychological testing.

A minority of patients had followed the recommendations, particularly when they involved cognitive rehabilitation. Recommendations involving psychotropic medications were more consistently followed. Patients who remembered at least some of the recommendations and patients who received both a written report and a phone call with results of neuropsychological testing had higher rates of adherence.

Adherence to recommendations may be improved by providing written and phone feedback, explaining the recommendations in depth, helping patients navigate insurance or find a provider, and having patients repeat back the recommendations.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Seng has received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (K23 NS096101) and served as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Julian LJ. Cognitive functioning in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2011;29:507–525.

Glanz BI, Healy BC, Rintell DJ, Jaffin SK, Bakshi R, Weiner HL. The association between cognitive impairment and quality of life in patients with early multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2010;290:75–79.

Julian LJ, Vella L, Vollmer T, Hadjimichael O, Mohr DC. Employment in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2008;255:1354–1360.

Niino M, Mifune N, Kohriyama T, et al. Apathy/depression, but not subjective fatigue, is related with cognitive dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:3.

Lester K, Stepleman L, Hughes M. The association of illness severity, self-reported cognitive impairment, and perceived illness management with depression and anxiety in a multiple sclerosis clinic population. J Behav Med. 2007;30:177–186.

Charvet L, Serafin D, Krupp LB. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Fatigue. 2014;2:3–13.

Koch MW, Patten S, Berzins S, et al. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a long-term longitudinal study. Mult Scler. 2015;21:76–82.

Moghadasi AN, Pourmand S, Sharifian M, Minagar A, Sahraian MA. Behavioral neurology of multiple sclerosis and autoimmune encephalopathies. Neurol Clin. 2016;34:17–31.

Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A, et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol. 2009;256:568–576.

Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R, et al. The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:69–77.

Turner A, Kivlahan D, Sloan A, Haselkorn J. Predicting ongoing adherence to disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: utility of the health beliefs model. Mult Scler. 2007;13:1146–1152.

Aminzadeh F. Adherence to recommendations of community-based comprehensive geriatric assessment programmes. Age Ageing. 2000;29:401–407.

Alosco ML, Spitznagel MB, Van Dulmen M, et al. Cognitive function and treatment adherence in older adults with heart failure. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:965–973.

Meth M, Calamia M, Tranel D. Does a simple intervention enhance memory and adherence for neuropsychological recommendations? Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2016;23:21–28.

Alosco ML, Spitznagel MB, Cohen R, et al. Better adherence to treatment recommendations in heart failure predicts improved cognitive function at a one-year follow-up. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2014;36:956–966.

Rosado DL, Buehler S, Botbol-Berman E, et al. Neuropsychological feedback services improve quality of life and social adjustment. Clin Neuropsychol. 2018;32:422–435.

Gorske TT. Therapeutic neuropsychological assessment: a humanistic model and case example. J Hum Psychol. 2008;48:320–339.

Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:25–38.

Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, DiMatteo MR. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1:189–199.

Benedict RH, Cookfair D, Gavett R, et al. Validity of the Minimal Assessment of Cognitive Function in Multiple Sclerosis (MACFIMS). J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12:549–558.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–515.

Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The Fatigue Severity Scale: application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:1121–1123.

Lerdal A, Wahl AK, Rustoen T, Hanestad BR, Moum T. Fatigue in the general population: a translation and test of the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Fatigue Severity Scale. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33:123–130.

Bower KM. When to use Fisher's exact test. Six Sigma Forum Magazine. 2003;2:35–37. Available at http://asq.org/pub/sixsigma/past/vol2_issue4/bower.html.

Trojano M, Lucchese G, Graziano G, et al. Geographical variations in sex ratio trends over time in multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48078.