Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Prevalence and Correlates of Body Image Dissatisfaction in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Body image dissatisfaction (BID) strongly predicts undesirable outcomes, including disordered eating, depression, and low self-esteem. People with multiple sclerosis (MS) may have higher BID due to changes in mobility and functioning and high rates of depression; however, little research has explored BID in people with MS. Identifying factors predicting BID in people with MS would help providers become more aware of BID and its possible negative outcomes.

Methods:

The sample included 151 adult patients with MS receiving care at the Cleveland Clinic Mellen Center for MS. The Body Shape Questionnaire was administered, and demographic information was collected from medical records. Data on MS-specific variables were collected via computerized testing. A one-sample t test, an independent-samples t test, and a hierarchical linear regression were conducted.

Results:

Average scores on BID were not significantly different from the population mean. Patients with moderate/marked concern were more likely to be female and had higher body mass index values, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores, and Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders Stigma T-scores. There were no age differences. No MS-specific variables significantly predicted BID.

Conclusions:

People with MS show approximately the same levels of BID as the general population. Higher BID was associated with being female and with higher body mass index, depression, and stigma. No MS-specific variables predicted higher BID after controlling for significant variables. Given the evidence in the literature of the negative effects of BID on health behaviors and mood, it is important to explore whether other factors affect BID in people with MS.

Body image dissatisfaction (BID), a discrepancy between a person's ideal body and their perceived body,1 is a strong predictor of a variety of undesirable outcomes, including disordered eating behaviors such as binge eating and binge eating disorder,2,3 depression,2,4,5 and low self-esteem.2,6 Women tend to show higher levels of BID than men, and more research has been conducted with women than with men.2 In fact, much of the literature on BID has been conducted on female adolescents, college students, or individuals with obesity seeking bariatric surgery,2,6,7 whereas body image in other populations, such as individuals with chronic medical illnesses such as multiple sclerosis (MS), has only recently begun to be examined.

Multiple sclerosis frequently involves the development of physical and emotional changes, including loss of function or feeling in limbs, sexual dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and alterations in mood.8 These changes are likely to lead to changes in body image, or the way an individual perceives, thinks, or feels about their body,1 which may lead to BID. In addition, 30% to 54% of people with MS experience symptoms of depression,8 which has been shown to correlate strongly with BID.2

However, there have been only three studies on BID in people with MS. The first study, published in 1985 by Halligan and Reznikoff,9 found that BID was highest soon after diagnosis, and it was unrelated to the extent of disability or depression. It is worth noting, however, that this study used projective measures of body image, which, according to the authors, had questionable validity. Projective measures are no longer used due to current literature supporting the higher accuracy of objective measures.10

Halligan and Reznikoff's results were also contradicted by the results of a study in 1989 by Samonds and Cammermeyer.11 This study examined 20 men with MS and found that degree of disability correlated with body image in these men to the same extent that it correlated in college-aged men. However, this study is nearly 30 years old, includes only men, and uses old measures with limited generalization. More recently, a study conducted in 2011 in Austria by Pfaffenberger et al12 found that compared with controls, individuals with MS reported significantly worse body appraisal and more negative feelings about their bodies. The authors also found a positive correlation between higher depression and higher BID for people with MS. In addition to the small number of studies in this area, two of the three studies are old and contradict one another, and the third did not assess many factors that may influence BID in people with MS, such as symptom severity, classification of MS, and medication.

Although there is little research on the impact of MS on BID, there has been some focus on the general effect of physical disability. Research examining the impact of physical disability may shed some light on the possible relationship between MS and BID. Research on acquired mobility disability (AMD) indicates that individuals with AMD seem to have body image comparable with their peers without AMD except that individuals with AMD showed increased body attention and perceived themselves to be less healthy.13 However, increased physical disability was related to higher BID in another study on women with physical disabilities related to spinal cord injuries and polio.14 Finally, a qualitative study of seven individuals with physical disabilities indicated the presence of BID related to these disabilities.15 Therefore, it is likely that MS and its physical changes would affect BID.

Because of the strong links between BID and poor health outcomes,2,6 it is important for clinicians to be able to determine risk factors in patients that may predispose them to BID and, therefore, poorer physical and mental health. The aims of this study were to explore levels of BID in patients with MS compared with community norms and to identify factors that predict BID in patients with MS, including both physical and psychological variables. If variables are found that predict BID, future research could explore the effectiveness of interventions targeted at improving body image and, consequently, other health outcomes in people with MS.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The study took place between November 28, 2017, and April 2, 2018, at the Cleveland Clinic Mellen Center for MS (Cleveland, OH). Inclusion criteria for the study were being older than 18 years, being diagnosed with MS, and receiving treatment for MS at the Mellen Center. Participants were recruited before or after medical or psychological appointments or while receiving medication infusions. After provision and signing of an informed consent document, the measure of body image was administered to patients. These questionnaires were entered into an electronic database on a password-protected computer in a locked office in a secure area of the building. Paper copies were kept in a locked file cabinet in this same office. After the collection of all patient questionnaires, data on demographic and MS-specific variables were collected with patient consent via electronic medical record. On measures with more than one data point, we chose the measurement closest to the time of questionnaire administration, with a 90-day proximity requirement. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Cleveland Clinic Mellen Center.

Measures

Demographic Data and Disease Course

Data on age, sex, race, marital status, median income, and body mass index (BMI) were collected via electronic medical record.

The course/classification of MS was determined by examining neurologist notes in patients' electronic medical records. Courses included monophasic (clinically isolated syndrome), relapsing-remitting, primary progressive, secondary progressive, and unspecified.

Disease-Modifying Therapy

The type of disease-modifying therapy a patient was receiving (if any) was identified by electronic medical record. Options included IFNβ-1a (Avonex; Biogen, Cambridge, MA), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, North Wales, PA), fingolimod (Gilenya; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp, East Hanover, NJ), alemtuzumab (Lemtrada; Sanofi Genzyme, Cambridge, MA), ocrelizumab (Ocrevus; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA), rituximab (Rituxan; Genentech), dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera; Biogen), natalizumab (Tysabri; Biogen), and none.

Timed 25-Foot Walk Test

The Timed 25-Foot Walk test (T25FW) measures mobility and leg functioning using the time it takes for a person to walk 25 feet as quickly as possible. The task is administered twice by a trained examiner, and the times of the two trials are averaged to obtain the score. The T25FW has been shown to be useful and reliable for measuring walking ability and has shown good reliability and validity.16

Quality of Life

The Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders (Neuro-QoL) scale was used to evaluate quality of life related to upper and lower extremity functioning and stigma.17 This measure examines self-reported quality of life in three main areas (physical, mental, and social health), using 13 scales. The present study uses three scales: Lower Extremity Function (mobility), Upper Extremity Function (fine motor, activities of daily living), and Stigma. The Stigma scale measures the perceived frequency of other's negative reactions toward the participant related to the illness. A sample item is, “Because of my illness, some people avoided me.” All the scales on the Neuro-QoL have been validated in people with MS and have shown good reliability.

Depressive Symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)18 was used to measure depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 measures frequency of symptoms over a 2-week period using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). A sample item is, “During the past month, how often have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?” This scale has shown good reliability and validity in previous studies.18

Body Image Dissatisfaction

The Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) is a 34-item scale developed in 198719 and has shown good reliability (α = 0.95) and validity.19 Two 16-item short-forms (A and B) were developed in 1993 by Evans and Dolan.20 Each short-form has separate forms for men and women (the word women is replaced by men in the male version); this occurs twice in form A and once in form B. The BSQ short-form B was used to prevent fatigue and interference with patient flow in the clinic and to provide the smallest difference between the different-sex scale forms. It examines individuals' frequency of different feelings about their appearance during the past 4 weeks on a 6-point scale from 1 (never) to 6 (always). A sample item is, “Have you been so worried about your shape that you have been feeling that you ought to diet?”

For short-form B, the main author suggested the following cutoff scores for the general population: less than 38, no concern with shape; 38 to 51, mild concern with shape; 52 to 66, moderate concern with shape; and greater than 66, marked concern with shape.21 The Cronbach alpha for the present study was 0.95. The remaining analyses (independent-samples t test and hierarchical linear regression) included the patients who completed all BSQ questions.

Statistical Analyses

One-Sample t Test

The mean BSQ total score in the cohort was compared with 38.36 (the mean value found in the study by Evans and Dolan20). A one-sample t test was performed to test whether the mean in this cohort differed from 38.36. This was repeated for men and women. We corrected for multiple testing using the Holm method.22

Simple Group Differences

Patient and clinical characteristics are summarized using descriptive statistics for patients in the study cohort overall and stratified by BSQ score less than 52 versus BSQ score of 52 or greater (ie, no/mild concern vs moderate/marked concern with body image). Group comparisons were made using independent-samples t tests or, when necessary, Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables.

Hierarchical Linear Regression

To see which factors were associated with BID, a hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted with the BSQ score as the dependent variable. Variables that have been shown in the literature (eg, in the study by Grilo et al2) to predict BID were entered in the first step (age, BMI, depression, sex). We also determined a priori that any variables found in preliminary analyses to predict BID (such as marital status, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status/zip code) would also be included in the first step. The second step added MS-specific variables (any disease-modifying therapy use, duration of MS, classification of MS), as well as Neuro-QoL Upper and Lower extremity T-scores and Neuro-QoL Stigma T-score. Adjusted R 2 values were computed for both models, and a Wald test was performed to determine whether the model in the second step fit significantly better than that in the first step. Residual plots were created to assess the assumptions of linear regression. Missing data were handled with multiple imputation, using 100 imputed data sets.

All computations were performed using R, version 3.4.1.23 All the tests were two-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Participants

A total of 152 patients completed the study; however, one of these patients was 17 years old at the time of questionnaire completion and was, thus, excluded from further analysis. For the remaining 151 patients, the mean ± SD age was 46.1 ± 11.8 years, with 66.2% female and 73.5% white.

One-Sample t Test

Of the 151 patients in the cohort, 142 completed all 16 BSQ questions. Of the nine who did not, one patient skipped three items and the other eight skipped one item. Among the 142 patients, the mean ± SD total score was 39.13 ± 18.10, indicating mild concern with shape. This score was not significantly different from 38.36 (the mean value from Evans and Dolan20) (P = .61). If all nine of these patients had responded with the highest item score for missing items, their total BSQ score would still have placed them in the same dichotomized category (no/mild vs moderate/marked concern), so we included these patients in all subsequent analyses. When examined separately by sex, men (mean ± SD: 33.37 ± 12.51) showed significantly lower BID than the population average (P < .02), and there remained no difference for women (mean ± SD: 42.36 ± 19.93, P = .117).

Simple Group Differences

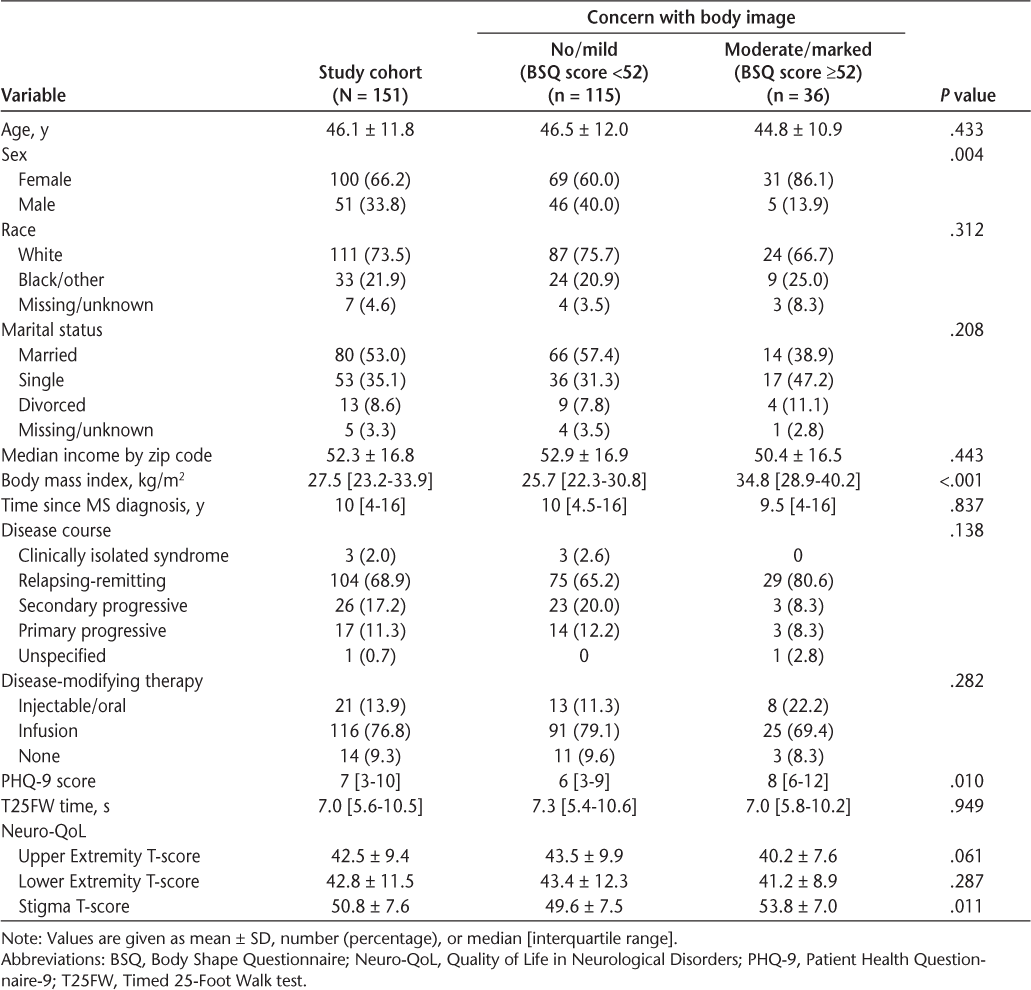

Patients with a BSQ total score of 52 or higher (indicating moderate/marked concern with body image) were more likely to be women (P < .005) and to have a higher median BMI (P < .001), a higher median PHQ-9 score (P < .02), and higher mean Neuro-QoL Stigma T-scores (P < .02). There were no differences between groups in age, race, marital status, median income, disease course, disease-modifying therapy, T25FW time, Upper Extremity scores, or Lower Extremity scores. See Table 1 for additional details.

Descriptive statistics for the full study cohort and stratified by BSQ total score

Hierarchical Linear Regression

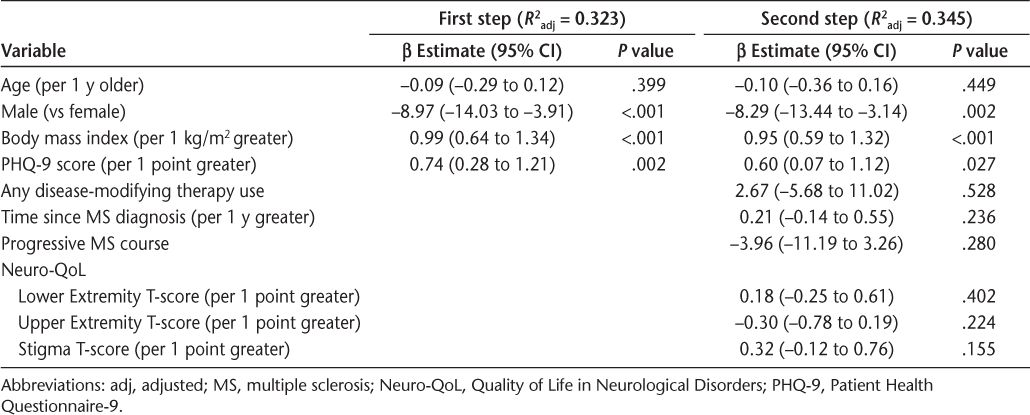

In the first step of the hierarchical linear regression, sex, BMI, and PHQ-9 score were significant predictors of total BSQ score (all P < .01, R 2 adj = 0.323). Age was not a significant predictor. In the second step, no additional variables were significant, and a Wald test indicated that the model fit was not significantly improved by adding these variables (P = .158, R 2 adj = 0.345). Because the second model was not a significant improvement over the first, the β values from the first model were interpreted. After adjusting for other covariates, men had BSQ total scores that were 8.97 points lower than those of women, on average. For each 1-kg/m2 increase in BMI, the average BSQ total score increased by 0.99 points. For each 1-point increase in PHQ-9 score, the average BSQ total score increased by 0.74 points. See Table 2 for full data.

Results of hierarchical linear regression analysis with Body Shape Questionnaire total score as a dependent variable

Discussion

This study explored the prevalence and correlates of BID in a sample of people with MS. Results indicated that, overall, people with MS do not show significant differences in BID from the general population. In addition, MS-related variables did not seem to affect MS in the sample overall. These results are in contrast to a previous study showing higher levels of BID in people with MS compared with the general population.12 This lack of significance may be due to sex differences or a small sample size.

Specifically, when BID was examined separately by sex it was found that men with MS showed significantly lower BID than the general population, whereas women showed a higher level of BID (although this difference was not statistically significant). Previous literature has established that women tend to have higher levels of BID than men,7 and the BSQ has been used primarily with women, who also compose the normative sample.18 Therefore, men in this study may show lower levels of BID not because they have MS but because they are male. In addition, a larger sample size would help determine whether the difference noted for women is nonsignificant due to low sample size or due to an actual lack of a relationship between having MS and higher BID.

The analyses examining group differences indicated similar findings to one another—variables previously shown in the general population to predict increased BID, such as higher BMI, increased depressive symptoms, and being female,1,3,4,7 also predicted higher BID in this sample. The relationship between higher depressive symptoms and higher BID is consistent with the study by Pfaffenberger et al.12 However, that study did not examine BMI or female sex as predictors of the extent of BID.

In the present study, the results of the independent-samples t tests and the hierarchical linear regression were identical except that stigma was a significant predictor only in the t tests, with more stigmatizing experiences predicting higher BID. The main factor affecting the difference in significance is likely sample size; a larger sample size may be required to detect the impact of stigma on BID when using a complex analysis such as hierarchical linear regression, which requires higher power and, thus, a larger sample size. The finding that higher stigma experience predicts increased BID is consistent with previous literature on the effects of weight stigma on BID24,25; however, to our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the effect on BID of generalized stigma or stigma related to neurologic conditions.

The lack of significance for the relationships between MS-related variables and BID is likely due to low power from a small sample size and relatively complex analyses. Although this finding would conflict with previous literature12 and with patient self-report, it is possible that MS and its related factors do not affect BID. In this study, T25FW performance showed very little difference between the group of individuals with moderate/marked concern and those with no/mild concern; in fact, although the difference is not significant, individuals with more BID actually performed the walk more quickly (mean, 7.0 vs 7.3 seconds). Both groups showed a mean time that would indicate a moderate impact of MS on daily life.26

It is also worth noting that many questions on the BSQ focus on body size and shape, with a tendency toward disliking larger size. A measure developed specifically for people with MS might more accurately measure BID in this population, as these individuals may experience BID due to losing weight or the physical changes associated with MS (eg, loss of function, changes in gait, muscle weakness/spasticity). Indeed, some literature has shown a lower average BMI in women with MS versus women without MS.27 Therefore, the lack of significance may also be due to the measure being developed for the general population versus specifically for people with MS.

Although this study is important in its examination of a little-studied topic, it has several limitations. Factors shown in the literature to be related to BID, such as eating behaviors and self-esteem,2–6 were not examined. In addition, this study included a large number of individuals receiving infusion therapies, a sample that may not be typical of people with MS and may render the results ungeneralizable. The study also used a general measure of BID rather than an MS-specific measure. Although no MS-specific measure currently exists, it is likely that data on MS-specific BID concerns are lost due to this.

In conclusion, this study examined BID in people with MS, finding similar levels as in the general population. In addition, the relationships between the examined variables echoed what has been seen in previous literature examining individuals without MS. In this study, a few variables were found to predict higher BID, including higher BMI, stronger symptoms of depression, being female, and experiencing more stigma. However, additional studies on body image in people with MS are needed. Future studies should include larger sample sizes to reduce the possibility of lower power contributing to lack of significance. These studies could examine the effects of different types of stigma (eg, weight-related, mobility-related, speech-related) on BID in people with MS. Examining sex differences in a larger sample would also help clarify the potential interaction between MS diagnosis and sex. Future research could also examine mediators and moderators of the relationships among these variables to provide an even clearer picture. The end goals are to identify predictors of increased BID in people with MS and to develop interventions focused on ameliorating these factors. Given the research showing the negative impact of BID on health behaviors, depression, and quality of life, this is an important area for continued examination.

PRACTICE POINTS

Body image dissatisfaction (BID) is a concern in patients with MS, at least as much as in the general population.

Previous literature on the general population has shown that as BID increases, individuals have a greater likelihood of experiencing depression, poorer eating behaviors, and poorer adherence to treatment recommendations.

Women, individuals with higher body mass index, individuals with more severe depressive symptoms, and individuals experiencing more stigma are at increased risk for BID.

Financial Disclosures:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Grogan S. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women, and Children. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2008.

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Brody M, Burke-Martindale CH, Rothschild BS. Binge eating and self-esteem predict body dissatisfaction among obese men and women seeking bariatric surgery. Eat Disord. 2005;37:347–351.

Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Obesity and body image. Body Image. 2004;1:43–56.

Friedman KE, Reichmann SK, Costanzo PR, Musante GJ. Body image partially mediates the relationship between obesity and psychological distress. Obesity. 2002;10:33–41.

White MA Grilo CM. Ethnic differences in the prediction of eating and body image disturbances among female adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38:78–84.

Rosenberger PH, Henderson KE, Grilo CM. Correlates of body image dissatisfaction in extremely obese female bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1331–1336.

Green SP, Prichard ME. Predictors of body image dissatisfaction in adult men and women. Soc Behav Pers. 2003;31:215–222.

Mohr DC, Cox D. Multiple sclerosis: empirical literature for the clinical health psychologist. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57:479–499.

Halligan FR, Reznikoff M. Personality factors and change with multiple sclerosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:547–548.

Cash TF, Smolak L. Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

Samonds RJ, Cammermeyer M. Perceptions of body image in subjects with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. J Neurosci Nurs. 1989;21:190–194.

Pfaffenberger N, Gutweniger S, Kopp M, et al. Impaired body image in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124:165–170.

Yuen HK, Hanson C. Body image and exercise in people with and without acquired mobility disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;6:289–296.

Moin V, Duvdevany I, Mazor D. Sexual identity, body image and life satisfaction among women with and without physical disability. Sex Disabil. 2009;27:83–95.

Taleporos G, McCabe MP. Body image and physical disability—personal perspectives. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:971–980.

Fischer JS, Jak AJ, Kniker JE, Rudick RA. Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC): Administration and Scoring Manual. New York, NY: National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2001.

Cella D; PROMIS Health Organization. Measuring Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders: Final Report of the Neuro-QoL Study. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/neuro_qol/NeuroQOL-Final_report-2013.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2018.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613.

Cooper PJ, Taylor MJ, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG. The development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord. 1987;6:485–494.

Evans C, Dolan B. Body Shape Questionnaire: derivation of shortened “alternate forms.” Int J Eat Disord. 1993;13:315–321.

Evans C. Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) and its shortened forms. https://www.psyctc.org/tools/bsq/. Accessed June 2, 2018.

Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed June 18, 2018.

Ashmore JA, Friedman KE, Reichmann SK, Musante GJ. Weight-based stigmatization, psychological distress, and binge eating behavior among obese treatment-seeking adults. Eat Behav. 2008;9:203–209.

Friedman KE, Ashmore JA, Applegate KL. Recent experiences of weight-based stigmatization in a weight loss surgery population: psychological and behavioral correlates. Obesity. 2008;16(suppl 2):S69–S74.

Goldman MD, Motl TW, Scagnelli J, Pula JH, Sosnoff JJ, Cadavid D. Clinically meaningful performance benchmarks in MS: Timed 25-Foot Walk and the real world. Neurology. 2013;81:1856–1863.

Markianos M, Evangelopoulos M, Koutsis G, Davaki P, Sfagos C. Body mass index in multiple sclerosis: associations with CSF neurotransmitter metabolite levels [published online September 24, 2013]. ISRN Neurol. doi:10.1155/2013/981070.