Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Assessing Stigma in Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

The stigma associated with neurologic disorders plays a part in poor health-related quality of life. The eight-item Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI-8) is a brief self-assessment tool for measuring perceived level of stigma. The psychometric performance of the SSCI-8 in people with multiple sclerosis (MS) was assessed.

Methods:

A multicenter, cross-sectional study in adults with relapsing-remitting or primary progressive MS was performed. A nonparametric item response theory procedure, Mokken analysis, was done to preliminarily study the dimensional structure of the SSCI-8. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model was then fit, and the behavior and information covered by the eight items were assessed by parametric item response theory analysis.

Results:

A total of 201 patients (mean ± SD age, 43.9 ± 10.5 years; 60.2% female; 86.1% with relapsing-remitting MS) were studied. The Mokken analysis found that the SSCI-8 is a unidimensional strong scale (scalability index H = 0.56) with high reliability (Cronbach α = 0.88). The CFA model confirmed the unidimensionality (comparative fit index = 0.975, root mean square error of approximation = 0.077). The information covered by the SSCI-8 items ranges from 3.79 to 13.52, for a total of 66.56. More than half (66%) of the SSCI-8 overall information is conveyed by four items: 1 (“Some people avoided me”), 2 (“I felt left out of things”), 3 (“People avoided looking at me”), and 7 (“People were unkind to me”).

Conclusions:

The SSCI-8 shows appropriate psychometric characteristics and is, therefore, a useful instrument for assessing stigma in people with MS.

Stigma associated with chronic illnesses may contribute to lowered self-esteem, depression, anxiety, poor quality-of-life outcomes, and decreased service utilization.1,2 People with multiple sclerosis (MS) can become dependent on others, need assistance to perform daily activities, and have major educational and occupational problems.3 However, the impact of stigma in multiple sclerosis (MS) has been little explored. An online survey conducted in the United States using a combination of stigma measures found that perceptions of stigma were relatively low in people with MS.4 Another study found that higher levels of stigma were significantly associated with more depressive symptoms.5 In a sample of 342 people with MS from Greece, stigma showed statistically significant negative correlations with both physical and mental health dimensions of the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life–54 questionnaire.6 Individuals with more self-stigma also experienced poorer quality of life in a Dutch study using the World Health Organization quality-of-life measurement instrument–abbreviated version.7 Perception of stigma was also associated with greater caregiver burden (odds ratio, 3.83; 95% CI, 1.84–7.96) in a survey of 530 patients with MS from Canada.8

Understanding stigma in MS may be crucial for performing specific intervention strategies against the internalized cognitive, emotional, and behavioral impact of the negative attitudes of others on a patient with a chronic illness.2 However, this requires appropriate instruments to assess stigma and the impact of interventions aimed at managing at least some of the negative cognitions and behaviors. Rao et al2 designed the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI) to assess the perception of stigma as part of the Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders study. This 24-item instrument was developed from responses to focus groups, a literature review of items, and cognitive interviews, and it evaluates two dimensions of stigma: enacted and internalized stigma. Enacted stigma refers to the negative attitude and experience of unfair treatment by others (discrimination). Internal stigma refers to the shame and expectation of discrimination that prevents people from talking about their experiences and stops them from looking for help (self-stigmatization). The same research team then developed a shorter version of the questionnaire, the SSCI-8.9 This eight-item version demonstrated validity and internal consistency across a sample of people with different neurologic disorders. However, there is limited information about the psychometric performance of the SSCI-8 in MS.

The aim of this study was to assess the dimensional structure and construct validity of the SSCI-8 in the management of people with MS.

Methods

Previously, a noninterventional, cross-sectional study in adults with relapsing-remitting or primary progressive MS (McDonald 2010 criteria10) was conducted in 18 MS units throughout Spain.11 The aim of this earlier study was to assess the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Multiple Sclerosis Work Difficulties Questionnaire.11 Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Investigators included the first ten consecutive people with MS who met the inclusion criteria for participating in the study. Competitive recruitment was established among centers. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Fundación Jiménez Díaz (Madrid, Spain). We performed a post hoc analysis using data from the aforementioned study to assess the psychometric performance of the SSCI-8.

The SSCI-8 scores items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Total scores range from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stigma. The SSCI-8 has shown high internal consistency, validity, and unidimensional structure for the underlying construct of perceived stigma.9 We used the Spanish version of the SSCI-8 instrument.12

Statistical Analyses

For continuous data, descriptive statistics are expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). For categorical data, descriptive statistics are expressed as frequencies and percentages.

A nonparametric item response theory (IRT) procedure, Mokken analysis, was conducted to assess the dimensional structure of the SSCI-8.13,14 Mokken analysis is a scaling procedure for tests and questionnaire data that involves an item selection algorithm to partition a set of items into scales. We fit two Mokken models: the monotone homogeneity model and the double monotonicity model. The monotone homogeneity model assesses the validity of the SSCI-8 total score for ordering and classifying participants according to the level of the underlying construct. The double monotonicity model is a more restrictive model because it also assumes the existence of an implicit order among the items. Whereas the monotone homogeneity model is associated with a two-parameter logistic model with parameters for difficulty (severity) and discrimination, the double monotonicity model is associated with a 1-parameter logistic model that assumes equal discrimination across items. All items were required to have a scalability coefficient (Hi) of at least 0.30, and the overall scale a scalability coefficient (H) of at least 0.30. Mokken suggested the following thresholds for interpreting scalability coefficients: weak scale, H of 0.3 to less than 0.4; medium scale, H of 0.4 to less than 0.5; and strong scale, H of 0.5 or greater.15 The internal reliability of the SSCI-8 scale was assessed according to Cronbach and Mokken estimates.

A parametric IRT model, the general partial credit model, was fit to obtain estimates of the relationship between the latent construct and the item characteristics.15 We estimated item response characteristic curve parameters and item information to assess the discrimination between category thresholds (probability of response to a specific item category given the level of difficulty of the attribute being measured) and the trait measurement precision of each item, respectively.

Finally, we fit a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model to assess the dimensionality of the SSCI-8 scale. We evaluated CFA goodness-of-fit with the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The CFI evaluates the fit of a user-specified solution with respect to a more restricted, nested baseline model (null model). The RMSEA evaluates the extent to which a model reasonably fits the population. We considered a CFI value greater than 0.95 as an acceptable model fit, and RMSEA values less than 0.08 and less than 0.05 as adequate and good model fit, respectively.16

We used the statistical program R, with the libraries “mokken,” “ltm,” “lavaan,” and “semPlot,” to perform the analyses.17–20

Results

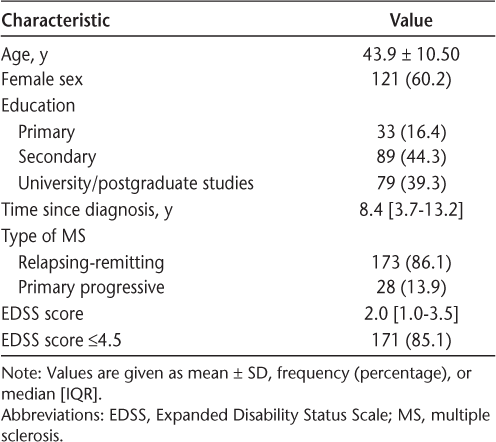

A total of 201 patients were included in the study. Patients were predominantly female (60.2%), with a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS (86.1%), and a mean ± SD age of 43.9 ± 10.5 years. The median SSCI-8 score was 10.0 (interquartile range, 8.0–14.0). Forty patients (19.9%) had at least one item with a score of 4 or 5, suggesting the presence of stigma “often” or “always.” The main sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 201 study participants

Internal Reliability

Cronbach α reliability was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.85–0.90) and Mokken reliability was 0.90. The mean interitem correlation was 0.49. The overall Cronbach α reliability would not be improved by removing any item (change to 0.87 without item 6 or 8; change to 0.86 without items 1, 2, 3, and 5; no change without items 4 and 7).

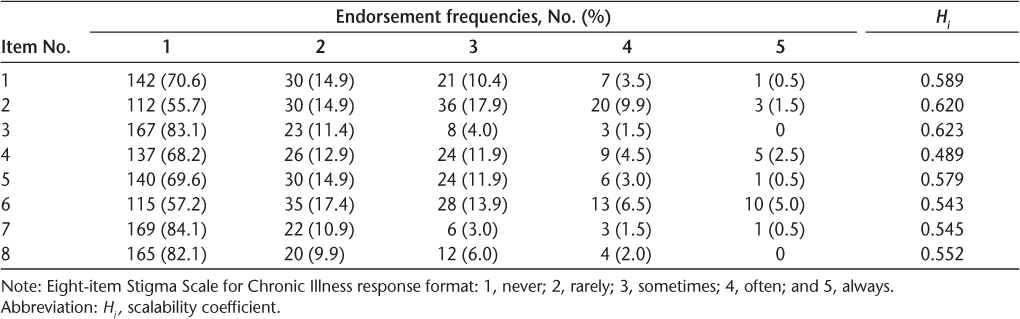

Nonparametric (Mokken) IRT

Table 2 shows the endorsement frequencies and Mokken scalability coefficients. The SSCI-8 is a unidimensional strong scale (scalability index H = 0.56), with all items showing scalability coefficients Hi greater than 0.40. The SSCI-8 shows a good fit to the monotone homogeneity model, indicating different item discrimination, but not to the double monotonicity model, which shows a relevant number of assumption violations for nearly all items.

Endorsement frequencies and Mokken scalability coefficients

Item Characteristics: General Partial Credit Model

More than half (66%) of the SSCI-8 overall information is conveyed by four items: item 1, “Some people avoided me”; item 2, “I felt left out of things”; item 3, “People avoided looking at me”; and item 7, “People were unkind to me.” The sorting order of item information was as follows: 3 (13.52), 7 (10.95), 1 (10.67), 2 (8.99), 5 (7.80), 8 (6.66), 6 (4.18), and 4 (3.79). Most items show a shape and category threshold compatible with appropriate difficulty and discrimination parameters (Figure S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org). Only items 4 and 6, those having the lowest information, showed crossing thresholds.

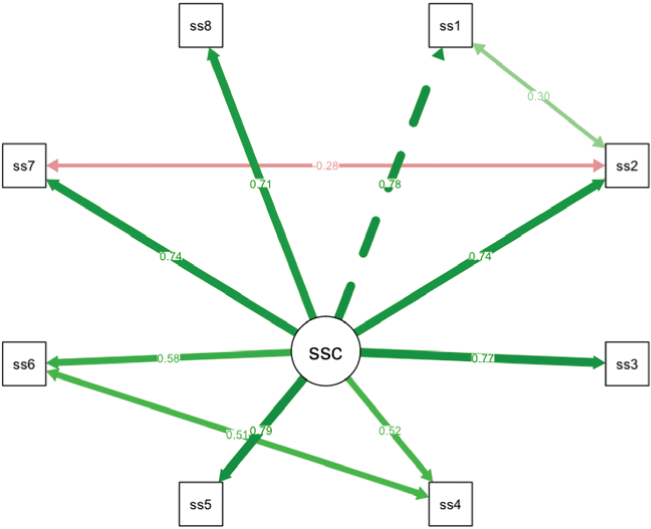

Factor Structure

The CFA model confirmed that the SSCI-8 fits well to a unidimensional structure (CFI = 0.975, RMSEA = 0.077). Inspection of standardized residuals and modification indices indicated no localized points of ill fit in the final solution except for including correlated measurement error between some items (1 with 2, 2 with 7, and 4 with 6). All freely estimated unstandardized parameters were significant (P < .001). Figure 1 shows the underlying structure of the SSCI-8, with standardized parameter estimates and correlated items. All the parameter estimates showed salient loadings (>0.40).

Confirmatory factor analysis

Discussion

Stigma is a psychosocial challenge that negatively affects the physical and mental health of people living with MS.5–7,21 In recent decades, there has been a major shift in the physician-patient relationship; patients are insisting on playing a more active role in decision-making processes related to their medical care.22 Identifying stigma using easy-to-implement patient-reported instruments might be relevant in terms of greater patient engagement.

This study reports the psychometric properties of the SSCI-8 in a sample of 201 people with MS. The SSCI-8 shows high internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.88), is a strong scale by the Mokken criteria (H = 0.56), and has a unidimensional structure according to CFA results, with all items showing salient loadings (>0.50). These results are consistent with those found in previous studies.9,23 Combining the internal reliability found in the present and previous studies, the pooled Cronbach α is 0.89 (95% CIs, 0.88–0.90). Molina et al9 and Yoo et al23 do not provide factor loadings from CFA for comparison with ours. However, the results of the three studies converge on the existence of a unidimensional structure underlying the stigma construct as evaluated using the SSCI-8. It means that according to the present results, it is possible to use the total score of the SSCI-8 as an overall summary of stigma.

A limitation of this study is that the unidimensional solution for the SSCI-8 structure includes three residual correlations among items. This points to some redundancy in the information covered by those items because they share variance of the stigma construct. The IRT results show that more than 50% of the information is compatible with just four of the eight items of the scale. If needed, a rewording of the offensive items might allow for a cleaner factorial solution as well as a further reduction of the scale. In addition, the study population was composed of a sample of clinically stable patients with low physical disability. Therefore, results might not be generalizable to patients who are less stable. Despite this limitation, the sample of 201 patients was managed in 18 MS units on a national level, thus allowing the results to be generalized to community practice.

In conclusion, the SSCI-8 demonstrates appropriate psychometric characteristics and fits a unidimensional latent trait of stigma; therefore, it is a useful instrument to assess stigma in people with MS. Multidisciplinary teams managing MS could use this instrument to determine which interventions are most necessary for targeting stigma.

PRACTICE POINTS

Although the negative impact of stigma on health-related quality of life outcomes has been highlighted for different neurologic disorders, the experiences of people with MS have been less studied.

Understanding stigma may be crucial for performing specific intervention strategies to achieve greater engagement between people with MS and health care professionals.

The eight-item Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI-8) shows appropriate psychometric characteristics and is a brief and useful self-rated instrument to assess stigma in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the patients and their families for making the W-IMPACT study possible. We also thank Fuensanta Sola and Cristina Garcia Bernáldez for leading the operational aspects of the study. The W-IMPACT Study Group: Adrián Ares (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León, León, Spain), Carmen Arnal (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Granada, Granada, Spain), Ana B. Caminero (Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles, Ávila, Spain), María Carcelén (Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia, Spain), Olga Carmona (Hospital de Figueres, Figueres, Spain), Pablo Eguía (Hospital Dr. José Molina Orosa, Lanzarote, Spain), María del Carmen Fernández (Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme, Sevilla, Spain), Lucía Forero (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cádiz, Spain), José M. García-Domínguez (Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain), Ricardo Ginestal (Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain), Laura Lacruz (Hospital Francesc de Borja, Gandía, Spain), Miguel Llaneza (Hospital Arquitecto Marcide, Ferrol, Spain), Carlos López de Silanes (Hospital de Torrejón, Torrejón de Ardoz, Spain), Gisela Martín (Hospital Verge de la Cinta, Tortosa, Spain), María L. Martínez-Ginés (Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain), Laura Navarro (Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Spain), Beatriz Romero (Hospital Son Llatzer, Palma, Spain), María Seral (Hospital General San Jorge, Huesca, Spain), and Myriam Solar (Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes, Gijón, Spain).

References

Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. J Health Psychol. 2012;17:157–168.

Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, et al. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI). Qual Life Res. 2009;18:585–595.

Kobelt G, Thompson A, Eriksson J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler. 2017;23:1123–1136.

Cook JE, Germano AL, Stadler G. An exploratory investigation of social stigma and concealment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2016;18:78–84.

Cadden MH, Arnett PA, Tyry TM, et al. Judgment hurts: the psychological consequences of experiencing stigma in multiple sclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2018;208:158–164.

Anagnostouli M, Katsavos S, Artemiadis A, et al. Determinants of stigma in a cohort of Hellenic patients suffering from multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:101.

Broersma F, Oeseburg B, Dijkstra J, et al. The impact of self-perceived limitations, stigma and sense of coherence on quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: results of a cross-sectional study. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32:536–545.

Hategeka C, Traboulsee A, McMullen K, et al. Stigma in multiple sclerosis: association with work productivity loss, health-related quality of life and caregivers' burden. Neurology. 2017;88(supp):P3.332.

Molina Y, Choi SW, Cella D, et al. The Stigma Scale for Chronic Illnesses 8-item version (SSCI-8): development, validation and use across neurological conditions. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20:450–460.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302.

Martínez-Ginés ML, García-Domínguez JM, Forero L, et al. Spanish validation of a specific measure to assess work-related problems in people with multiple sclerosis: the Multiple Sclerosis Work Difficulties Questionnaire (MSWDQ-23). Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;22:115–119.

Correia H, Pérez B, Arnold B, et al. Spanish translation and linguistic validation of the quality of life in neurological disorders (Neuro-QoL) measurement system. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:753–756.

Mokken RJ. Nonparametric models for dichotomous responses. In: van der Linden WJ, Hambleton RK, eds. Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010:351–367.

Molenaar IW. Nonparametric models for polytomous responses. In: van der Linden WJ, Hambleton RK, eds. Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010;369–380.

Muraki E. A generalized partial credit model: application of an EM algorithm. Appl Psychol Meas. 1992;16:159–176.

Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

Van der Ark LA. Mokken scale analysis in R. J Stat Softw. 2007;20:1–19.

Rizopoulos D. ltm: an R package for latent variable modeling and item response theory analyses. J Stat Softw. 2006;17:1–25.

Rosseel Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48:1–36.

Pérez-Miralles F, Prefasi D, García-Merino A, et al. Perception of stigma in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019;5:2055217319852717.

Rieckmann P, Centonze D, Elovaara I, et al. Unmet needs, burden of treatment, and patient engagement in multiple sclerosis: a combined perspective from the MS in the 21st Century Steering Group. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;19:153–160.

Yoo S-H, Kim SR, So HS, et al. The validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness 8-items (SSCI-8) in patients with neurological disorders. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24:288–293.