Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Adapting to Multiple Sclerosis Stigma Across the Life Span

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Most people with multiple sclerosis (MS) experience social stigma at mild-to-moderate levels, with potential implications for their health. However, little is known about how adults adapt to social stigma across their lives, or with respect to MS stigma in particular. Using a large national database and controlling for confounding demographic and health-related variables, this study examined whether longer MS duration was associated with reports of stigma in people with MS.

Methods:

Data were available from 6771 participants enrolled in the semiannual survey conducted by the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS). Participants completed measures of MS stigma and reported on demographic and health-related covariates.

Results:

With disability level, age, and other demographic and health-related covariates taken into account, the longer respondents had lived with MS, the less stigma they felt. Results were similar for people's anticipation of stigma and their feelings of isolation because of stigma.

Conclusions:

As people gain experience living with MS, their adaptations to the social aspects of their illness may allow them to structure their lives so that they can mitigate the impact of stigma. Doctors, therapists, and other health care personnel should consider that patients with MS might be especially concerned and distressed by stigma earlier in the course of their illness.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system that often develops between ages 20 and 40 years, affects more women than men, and has no known cure.1,2 Symptoms include sensory disturbances, fatigue, weakness, pain, balance issues, bladder and sexual dysfunction, depression, vision loss, and cognitive impairment.2 The course of MS is unpredictable and varies widely, but most people (85%) initially have acute symptom attacks followed by periods of partial or full symptom remission (relapsing-remitting MS). Over time, MS symptoms tend to progress and can lead to severe disability.2

Most people with MS experience social stigma as a result of their MS at mild-to-moderate levels,3,4 with potential implications for their health. Stigma occurs when people are labeled as different, separate, and of lower status based on some characteristic (such as MS), and are thus negatively stereotyped and/or discriminated against.5 In general, being a target of stigma is associated with a host of negative outcomes, such as poorer health, health care, social relationships, housing, and psychological, educational, and employment outcomes.6 The stigma of MS in particular has been linked to poorer quality of life and depression.3,7,8 People with MS report that stigma is a barrier to their daily functioning and resilience.7,9 Stigmatizing social interactions and isolation are at odds with the need to belong, which is considered a core human need that is vital to well-being.10 Conversely, social support and connection play important roles in counteracting stress and maintaining well-being11 and can help people cope with MS.9 Thus, stigma has negative implications for the overall quality of life of people with MS, making it important to better understand the factors associated with MS stigma.

Stigma is dynamic in that it is not stable for a given individual across time but rather varies across relationships and situations.12 People with MS must continually navigate how MS could affect their employment and social relationships, and whether and how to tell people about their illness.13 In response to experiences of stigma, people may adopt various strategies to mitigate future stigma experiences and use feedback from the success of these strategies to inform their future responses.14,15 That is, people are likely to improve in their ability to manage and mitigate future stigma experiences. For example, over time, people might adapt to MS by surrounding themselves with supportive others, educating others about their illness, and strategically choosing to conceal or disclose their MS status.13,16–18 If so, as people gain experience coping with MS, they may be less likely to anticipate or experience being a target of stigma.19–22 Consistent with this adjustment view, people with MS often describe developing a more positive, optimistic outlook over time.20 Thus, perhaps ironically, even as symptoms of MS progress, increasing the likelihood of stigma, people's experience and adaptations may help reduce the stigmatizing aspects of the illness.23

Very little research has examined whether stigma changes across the life span as people gain experience managing their membership in a stigmatized group. Given the association of stigma with health outcomes, this is an important topic to study. In people with MS, perceptions of MS stigma may differ, for example, from the time surrounding a diagnosis to years or decades later. Only a few studies have investigated whether stigma changes with time in MS, and these have yielded mixed results. In a bivariate analysis of MS duration and stigma, Anagnostouli and colleagues7 found that people with a longer duration of MS reported higher levels of stigma. However, this association became nonsignificant once disability status was controlled, suggesting that higher levels of stigma were due to participants' increased disability rather than to an increase in perceptions of stigma over time. This makes sense because the longer people have had MS, the more severe and debilitating their MS is likely to become.7 Increasing symptoms reduce coping resources and/or increase the frequency of stigmatizing experiences by making illness or disability more visible.7,19 The research by Anagnostouli and colleagues suggests that it is worsening symptoms that increase stigma, not the presence of the illness alone. However, other studies have reported nonsignificant bivariate associations between MS duration and stigma.3,4 Given the complex association between MS duration, disability status, and stigma, it is clear that accounting for relevant demographic and health status variables is necessary to understand how MS duration relates to stigma. Because examining this relationship has not been the central goal of most previous research,7 there is a need for more systematic investigation.

Independent of disease duration, age may be an important predictor of perceived stigma. Having more life experience in general might come with changes that affect the anticipation or experience of stigma. For example, as people age they may be able to make more effective use of emotion-regulating strategies,24 feel less distressed by daily hassles,25 and increase their attention to and memory of positive rather than negative information.26 Also, as people age, disability becomes more common and may, thus, be less stigmatized by peers. Although age and MS duration are obviously correlated, the focus herein is primarily on people's adaptation to MS rather than on general adaptation to stigma with age. Thus, we include age as a covariate in the analyses that follow. In addition, past research suggests that accounting for other relevant sociodemographic and health-related variables is necessary to get a clear picture of how MS duration relates to stigma.7 We, therefore, include such factors as covariates in this study (eg, sex, race, type of MS, and recent relapse).

The goal of this study was to examine, using a large national database, whether longer MS duration is associated with reports of stigma in people with MS. We tested this association after controlling for relevant demographic and health status variables—particularly disability level and age—that may otherwise obscure how stigma changes over time. We hypothesized that even as disability worsens, anticipation and experience of stigma may stay constant or even decrease as people structure their lives to minimize stigma. Because MS is a chronic, incurable disease that typically affects people from early adulthood through the rest of their lives, knowing whether and how individuals might adapt to better cope with stigma is key to understanding the experiences and needs of people with MS.

Methods

Survey

Data were collected in conjunction with the semiannual national survey of individuals with MS conducted by the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. NARCOMS maintains a database of adults with MS who voluntarily and confidentially report on a variety of health topics. Participants initially complete an enrollment survey that assesses demographic and health information, including age at diagnosis, and then are asked to fill out update surveys twice per year. Each update includes routine health questions and items regarding a special topic of interest. As part of the Spring 2013 update survey, we included self-report measures of stigma. More than 38,000 people have enrolled in the database, and approximately 8000 people typically participate in each update. Overall, respondents are primarily from the United States and are diverse in terms of MS disability status and sociodemographic characteristics.27 Demographically, participants are similar to people with MS in the representative National Health Interview Survey.28

Participants

The sample comprised the 6771 participants who completed the stigma measures that form the primary outcome. We examined whether these participants differed systematically in age, MS duration, and sex from participants who completed the same update survey but did not complete the stigma measures (n = 1642). There were no significant differences in age or sex (P > .50), although respondents who completed the stigma measures had MS for approximately 1 year longer than those who did not (mean ± SD duration, 19.64 ± 9.79 years vs 18.55 ± 9.35 years; t 8345 = −4.05, P < .001). Of the 6771 respondents who completed the stigma measures, 94 (1.4%) were missing values on a key continuous predictor (57 on MS duration and 37 on disability status). Excluding less than 5% of cases with missing values is unlikely to result in bias or to substantially affect power in such a large sample.29 Thus, we used a simple listwise deletion strategy for these cases, leaving a final sample size of 6677. Some participants had missing data on one or more categorical demographic and health-related covariates (described later herein). Because we envisioned these as potential confounds to control rather than essential to the analysis, we limited data loss by creating a separate category for each variable to represent nonresponders, consistent with past approaches using these data.8

Measures

Stigma

In the 2013 update survey, participants rated statements about stigma on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true). Nine items formed two stigma scales, as has previously been reported,8 with higher scores reflecting higher levels of stigma.

Anticipated stigma was an average of four items tapping into people's anticipation of or experiences with being a target of stigma: “People are uncomfortable around someone with MS,” “I always have to prove myself because of my MS,” “People who know that I have MS treat me differently,” and “Because of my MS, I worry about other people's attitudes toward me” (α = 0.78).

Isolation stigma was an average of five items tapping into people's sense of being socially isolated because of their MS: “Because of my MS, I feel left out of things,” “Because of my MS, I feel set apart, isolated from the rest of the world,” “Because of my MS, I worry that I am a burden to others,” “I feel embarrassed about my speech or physical limitations,” and “I can't fulfill many of my responsibilities because I have MS” (α = 0.86).

Age and MS Duration

Participant age was computed by subtracting year of birth (reported during enrollment) from 2013, the year of the update survey with the stigma scales. The length of time, in years, that participants had lived with MS was calculated by subtracting participant age in 2013 from age at diagnosis (reported at enrollment).

Disability Status

The Patient-Determined Disease Steps scale30 was used to assess disability status in the Spring 2013 update. Scores from 0 to 2 reflect mild or moderate symptoms that do not limit ability to walk. Scores from 3 to 5 indicate an occasional to consistent need for walking assistance such as a cane or help from another person. Scores of 6 and 7 indicate a need for bilateral walking assistance such as a wheelchair or scooter, and a score of 8 indicates that the individual is bedridden.

Categorical Covariates

Sex, race/ethnicity, and educational level were assessed as part of the enrollment survey, and employment status, smoking status, occurrence of a recent relapse, health insurance status, use of disease-modifying therapies, and MS type (eg, relapsing-remitting, progressive) were assessed as part of the 2013 update survey. All the categorical variables were dummy coded, including a category for missing data where appropriate.

Results

Study Participants

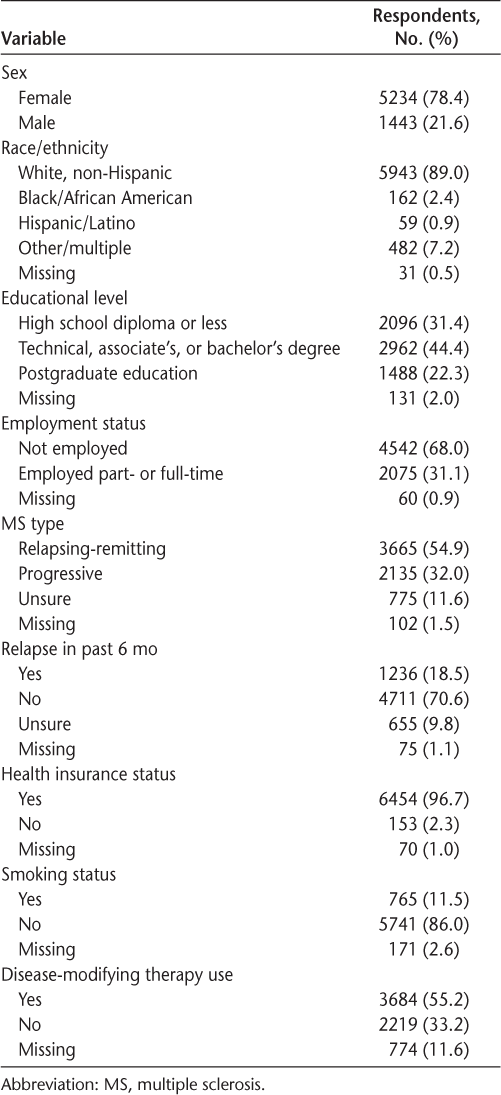

The final sample of 6677 respondents was 78.4% female with a mean ± SD age of 58 ± 10.48 (range, 23–93) years and an MS duration of 19.60 ± 9.76 (range, 1–67) years. Tables 1 and 2 provide descriptive information for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Participants were primarily white, well-educated nonsmokers with health insurance. Most were also unemployed. Most participants had a relapsing-remitting course of MS but had not relapsed in the past 6 months, and most were using a disease-modifying therapy. The mean ± SD disability status in this sample was 3.65 ± 2.41, corresponding to a moderate level of disability.

Descriptive statistics for categorical variables (N = 6677)

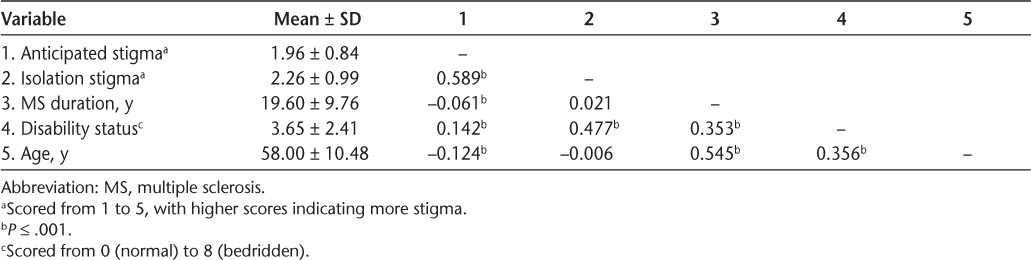

Descriptive statistics and correlations between continuous variables (N = 6677)

Stigma levels in the sample were relatively low on average but represented the full range (1–5) of the anticipated and isolation stigma scales. The mean anticipated stigma score was 1.96, falling just below slightly true, and the mean isolation stigma score was slightly higher at 2.26, falling between slightly true and somewhat true (Table 2). Most participants indicated experiencing each type of stigma to some degree, with only 18.2% reporting not experiencing anticipated stigma at all and 11.7% reporting no isolation stigma at all (indicated by a score of 1 = not at all true). The two stigma scales correlated at r = 0.59. As seen in Table 2, bivariate correlations revealed that older people had lower levels of anticipated stigma, but age was not associated with isolation stigma. There was a small but significant bivariate correlation between disease duration and anticipated stigma such that participants who had been diagnosed as having MS longer anticipated less stigma; but the bivariate association between MS duration and isolation stigma was nonsignificant. Finally, higher disability levels were associated with higher levels of anticipated stigma and isolation stigma (and also, as would be expected, longer MS duration and older age). In regression analyses later herein, stigma was associated in general with worse health, negative health behaviors, and a relative lack of resources (Table 3).

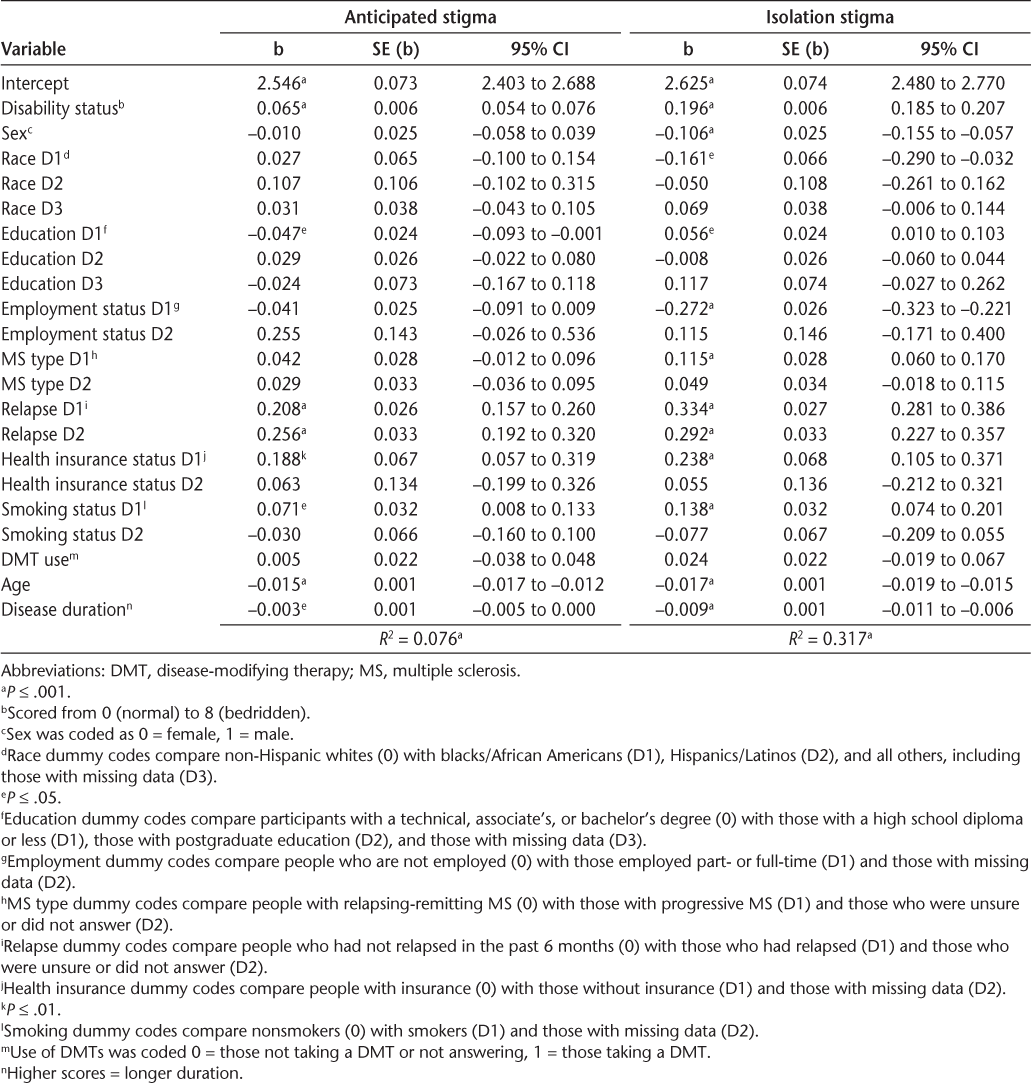

Regression coefficients for predictors of stigma (N = 6677)

Association Between Disease Duration and Stigma

To examine whether the length of time an individual has lived with MS is associated with changes in the degree to which they experience and anticipate social stigma, we conducted a hierarchical multiple regression analysis with the two stigma scales as separate outcomes. In the first step, demographic and health covariates were entered. Because one's age and disease duration overlap conceptually (the longer people have had MS, the older they must be) and past work generally does not address this overlap, one goal of this study was to determine whether MS duration predicts stigma beyond what is predicted by age. Therefore, age was added to the model in the second step, and then MS duration was added in the third step. We also examined the possibility of a nonlinear relationship between MS duration and stigma by testing a quadratic effect of disease duration. The quadratic term did not contribute significantly to the prediction of anticipated or isolation stigma, so it was dropped from the analyses presented later herein. Regression coefficients for the final model of each stigma outcome, as well as details of the coding strategy, are presented in Table 3.

Anticipated Stigma

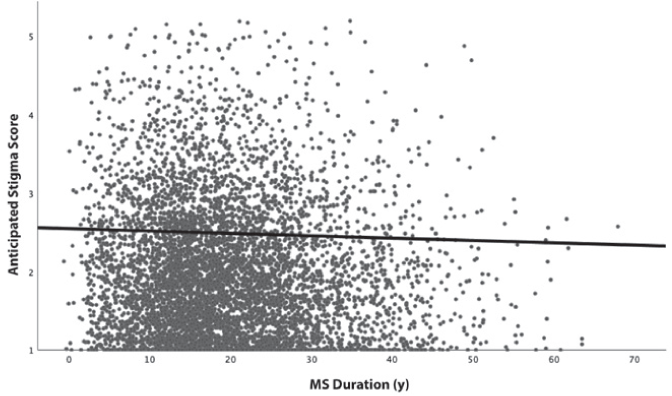

The demographic and health covariates entered in step 1 accounted for 4.80% of the variance in anticipated stigma (F 19,6657 = 17.58, P < .001). Adding age in step 2 increased the variance explained to 7.57% (ΔR 2 = .028, ΔF 1,6656 = 201.08, P < .001). After controlling for demographic and health status variables, older age was associated with lower levels of anticipated stigma. In step 3, disease duration accounted for a small but statistically significant amount of additional variance, increasing to 7.64% the variance explained in anticipated stigma from the model (ΔR 2 = 0.001, ΔF 1,6655 = 5.12, P = .024). That is, disease duration predicted anticipated stigma beyond what was accounted for by demographic and health status variables, including age. Specifically, people who had lived longer with MS reported lower levels of anticipated stigma (b = −0.003, SE = .001, 95% CI = −0.005 to −0.0004) (Figure 1). Age continued to be associated with lower anticipated stigma after controlling for MS duration. These results are consistent with the idea that people adapt to MS as they age and accumulate experience living with the illness.

Scatterplot of multiple sclerosis (MS) duration predicting anticipated stigma

Isolation Stigma

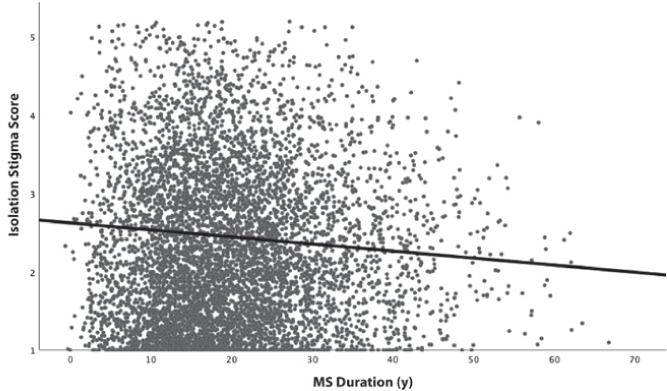

Demographic and health covariates entered in step 1 accounted for 27.85% of the variance in isolation stigma (F 19, 6657 = 135.21, P < .001). Adding age in step 2 increased the variance explained to 31.20% (ΔR 2 = .034, ΔF 1,6656 = 324.44, P < .001), with older age being associated with lower levels of isolation stigma. In step 3, MS disease duration made a small improvement to model fit, which now accounted for 31.67% of the variance in isolation stigma (ΔR 2 = 0.005, ΔF 1,6655 = 45.88, P < .001). Respondents who had lived with MS longer tended to report lower isolation stigma (b = −0.009, SE = 0.001, 95% CI = −.011 to −.006) (Figure 2). Age continued to be associated with lower isolation stigma in this model. Thus, older participants reported less isolation stigma. Participants with more experience with MS also reported less isolation stigma, even after adjusting for age.

Scatterplot of multiple sclerosis (MS) duration predicting isolation stigma

Discussion

Using a large national sample, this study empirically investigated how people's perceptions of MS stigma varied as a function of the length of time that they had been diagnosed as having MS. Results revealed a small but reliable effect indicating that, accounting for disability level, age, and other demographic and health-related covariates, the longer participants had lived with MS, the less stigma they felt. Results were similar for people's anticipation of stigma and their feelings of isolation because of stigma. These findings are consistent with the idea that gaining experience living with MS may be accompanied by adaptive coping processes. For example, people might, over time, surround themselves with a support system that helps them avoid many situations in which stigmatized treatment could occur, or they may be strategic about who to tell about their MS.13 This ability to adapt and manage social aspects of MS is consistent with other recent research suggesting that people with well-developed support systems and other psychological resources are more protected against harmful effects of stigma.8,13

Duration of MS predicted twice the variance in isolation stigma than in anticipated stigma, suggesting that adjustment processes might be more successful at reducing people's isolation due to MS stigma than the degree to which they experience and expect stigmatizing events. This difference might reflect that people with MS are better able to adapt to and reduce the degree to which they are isolated from others, whereas they might have less control over other people's perceptions of and behavior toward them. People with MS might, therefore, benefit most by focusing coping strategies on isolation stigma. Doctors, therapists, and other health personnel should consider that patients with MS might be especially concerned and distressed by stigma earlier in the course of their illness. Similarly, educational programs for people with MS and their families should take MS duration into account, and it might be comforting for people to know that dealing with stigma might become easier over time. Support groups for MS might be more helpful for recently diagnosed people if they involve exposure to people who have had MS longer who could be a resource in adjusting to and managing MS stigma.

Results reported herein are also consistent with recent research4,31 in finding that although stigma is commonly experienced by people with MS—with significant consequence—mean levels are not particularly high. This may be because MS has fewer stigmatizing attributes than some stigmatizing conditions. For example, people may be less likely to attribute the cause of MS to personal responsibility, as they might with other stigmatized identities.

We suggested that decreases in stigma with MS duration may be due to people's use of active coping strategies. However, there are also other possible reasons why stigma might decrease over time. One possibility is that stigma toward MS has decreased over time as public awareness of MS has risen and more effective treatments have emerged. If so, people who have had MS longer may have relatively lower expectations of stigma. Also, as people age, disabilities become more common, which may reduce stigma in similarly aged peers. As with any nonprobability sample, results may not generalize to the larger population of those living with MS or to those with other stigmatized group memberships. Because this analysis is cross-sectional, one direction for future research is to examine the association between MS duration and stigma longitudinally. It would also be helpful to examine constructs that might indicate what adaptation processes occur, such as the perceived effectiveness and frequency of use of various coping strategies over time (eg, the degree to which people surround themselves with supportive others or avoid certain types of social interactions). Further research into how people adapt to MS stigma over time might suggest useful strategies that can be taught or consciously used.

PRACTICE POINTS

Many people with MS experience social stigma, which predicts poorer physical and psychological health and quality of life.

People with stigmatized conditions such as MS may adapt over time to the social aspects of the illness and create social environments where disability is more accepted.

Using a large national sample, this study found that people who had lived with MS longer reported lower levels of stigma after controlling for confounding demographic and health-related variables, including age and disability status.

Financial Disclosures:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–1517.

Rejdak K, Jackson S, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis: a practical overview for clinicians. Br Med Bull. 2010;95:79–104.

Broersma F, Oeseburg B, Dijkstra J, Wynia K. The impact of self-perceived limitations, stigma and sense of coherence on quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: results of a cross-sectional study. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32:536–545.

Cook JE, Germano AL, Stadler G. An exploratory investigation of social stigma and concealment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2016;18:78–84.

Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385.

Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:813–821.

Anagnostouli M, Katsavos S, Artemiadis A, et al. Determinants of stigma in a cohort of Hellenic patients suffering from multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:101.

Cadden MH, Arnett PA, Tyry TM, Cook JE. Judgment hurts: the psychological consequences of experiencing stigma in multiple sclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2018;208:158–164.

Silverman AM, Verrall AM, Alschuler KN, Smith AE, Ehde DM. Bouncing back again, and again: a qualitative study of resilience in people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:14–22.

Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117:497–529.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–357.

Major B, O'Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:393–421.

Cook JE, Salter A, Stadler G. Identity concealment and chronic illness: a strategic choice. J Soc Issues. 2017;73:359–378.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984.

Miller CT, Kaiser CR. A theoretical perspective on coping with stigma. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:73–92.

Pasek MH, Filip-Crawford G, Cook JE. Identity concealment and social change: balancing advocacy goals against individual needs. J Soc Issues. 2017;73:397–412.

Grytten N, Måseide P. “What is expressed is not always what is felt”: coping with stigma and the embodiment of perceived illegitimacy of multiple sclerosis. Chronic Illn. 2005;1:231–243.

Vickers MH. Life at work with “invisible” chronic illness (ICI): the “unseen”, unspoken, unrecognized dilemma of disclosure. J Workplace Learn. 1997;9:240–252.

Driedger SM, Crooks VA, Bennett D. Engaging in the disablement process over space and time: narratives of persons with multiple sclerosis in Ottawa, Canada. Can Geographer. 2004;48:119–136.

Irvine H, Davidson C, Hoy K, Lowe-Strong A. Psychosocial adjustment to multiple sclerosis: exploration of identity redefinition. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:599–606.

Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J, González J-MM, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:556–566.

Soundy A, Roskell C, Elder T, Collett J, Dawes H. The psychological processes of adaptation and hope in patients with multiple sclerosis: a thematic synthesis. Open J Ther Rehabil. 2016;4:22–47.

Cook JE, Arrow H, Malle BF. The effect of feeling stereotyped on social power and inhibition. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2011;37:165–180.

Shiota MN, Levenson RW. Effects of aging on experimentally instructed detached reappraisal, positive reappraisal, and emotional behavior suppression. Psychol Aging. 2009;24:890–900.

Charles ST, Almeida DM. Genetic and environmental effects on daily life stressors: more evidence for greater variation in later life. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:331–340.

Reed AE, Chan L, Mikels JA. Meta-analysis of the age-related positivity effect: age differences in preferences for positive over negative information. Psychol Aging. 2014;29:1–15.

Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, Tyry T. Cumulative impact of comorbidity on quality of life in MS. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012;125:180–186.

Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Vollmer T. Validation of NARCOMS depression scale. Int J MS Care. 2008;10:81–84.

Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:549–576.

Hohol M, Orav E, Weiner H. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study comparing disease steps and EDSS to evaluate disease progression. Mult Scler. 1999;5:349–354.

Ballesteros J, Martínez-Ginés ML, García-Domínguez JM, Forero L, Prefasi D, Maurino J; W-IMPACT Study Group. Assessing stigma in multiple sclerosis: psychometric properties of the Eight-Item Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI-8). Int J MS Care. 2019;21:195–199.