Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Association of Unemployment and Informal Care with Stigma in Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Multiple sclerosis (MS) typically affects young adults during their primary productive years. We assessed the magnitude of, and factors associated with, employment status and informal care in people with MS in Canada.

Methods:

Data were compiled from the nationally representative cross-sectional Survey on Living with Neurological Conditions in Canada (SLNCC), which included adolescents and adults (age ≥15 years). Employment status was categorized as currently working or not working. The frequency of informal care that people with MS received was categorized as none, less than daily, or daily. Logistic regression analyses were undertaken to identify factors associated with employment status and informal care requirements in people with MS.

Results:

Of 4409 SLNCC respondents, 631 had MS, of whom 530 were included in the analysis. Of 358 respondents aged 18 to 65 years, 47.8% were not working because of MS; 44.0% reported receiving informal care, with more than half requiring daily care. For caregivers' employment, 15.5% reduced work and 8.2% stopped working because of caregiving. Greater feelings of stigmatization were associated with not working (adjusted odds ratio, 7.42 [95% CI, 2.59–21.28]) and greater informal care (adjusted odds ratio, 3.83 [95% CI, 1.84–7.96]), adjusting for sex, age, education, health-related quality of life, time since MS diagnosis, and comorbidity.

Conclusions:

People who feel stigmatized because of their MS are more likely to be unemployed and to require more informal care. Further research is needed to understand the temporal nature of the association between stigma and employment, productivity loss, and informal care.

Multiple sclerosis (MS), an immune-mediated demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, affects more than 2.3 million people globally.1,2 Canada has one of the highest rates of MS worldwide, with 93,535 people living with the disease in 2010–2011.2,3 Although MS still has no definitive cure, currently available treatments help to manage flare-ups, reduce the frequency of relapses, control symptoms, and potentially slow the progression of the disease.4–6 People experience MS differently based on their disease type, including relapsing-remitting, primary progressive, secondary progressive, and progressive relapsing.2,7 At the time of diagnosis (which usually occurs between 15 and 40 years of age), approximately 85% of people are diagnosed as having relapsing-remitting MS.2

Multiple sclerosis causes both physical and cognitive impairments, and it is the leading cause of neurologic disability in young adults during the primary productive time of their life.2,8 As such, MS exerts a significant burden not only on patients but also on their family members and friends, health care systems, and society. Research suggests that between half to two-thirds of people with MS leave employment within 10 years after disease onset.9,10 As such, the indirect cost of disease associated with work productivity loss in people with MS is substantial.11–14 For example, a review by Stawowczyk et al13 estimated the overall indirect costs associated with MS were more than US$20,000 per patient with MS per year. In particular, it has been suggested that direct work productivity loss (ie, the value of production forgone due to morbidity or mortality) in people with MS that is due to MS accounts for nearly half the cost associated with MS.12,15

Besides the financial implications associated with direct work productivity loss in MS, stopping work can have a negative effect on overall quality of life of people with MS,16 as well as on their sense of usefulness, satisfaction, and self-esteem.8 Moreover, employment has been suggested as a potential public health intervention for people with MS.17 Therefore, understanding factors that may contribute to retaining people with MS in the workforce, and targeting those that are modifiable, is important not only for health care and public health professionals but also for policy and decision makers to improve work productivity and health outcomes, including quality of life, of people with MS in Canada.

Multiple sclerosis exerts a significant burden on families and friends, for example, by necessitating informal care provision to people with MS. Caregiving for people with chronic conditions, including MS, can have a significant negative effect on the people providing care (ie, caregiver burden).18–20 Caregiver burden is defined as “a multidimensional response to physical, psychological, emotional, social and financial stressors associated with the caregiving experience.”20(p25) In particular, caregiver burden has been found to be associated with the frequency of informal care provided: the more caregiving required, the more caregiver burden is experienced.18 Moreover, a variety of studies have reported that greater caregiver burden may have a negative effect on people with MS (reciprocal effect) and the relationship between people with MS and their caregivers.19,21–23 Furthermore, caregiver burden has a negative effect on the work productivity of MS caregivers (ie, indirect work productivity loss).24,25 Therefore, identifying potential factors that may contribute to reducing informal care requirements in MS, and targeting those that are modifiable, is important not only for people with MS and their caregivers but also from a societal perspective to reduce the societal costs associated with direct and indirect work productivity loss in MS.

Given that Canada has one of the highest rates of MS, and, thus, the potential effect of MS on employment in people with MS and their caregivers,2,26 it is important to identify potential factors that are associated with unemployment and greater informal care requirements from a Canadian perspective. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the magnitude of, and identify factors associated with, both unemployment and informal care requirements in people with MS in a large and representative population-based sample of Canadians with neurologic conditions.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

We used data collected from the Survey on Living with Neurological Conditions in Canada (SLNCC).27 The SLNCC is a nationally representative population-based cross-sectional survey that was performed by Statistics Canada in 2011 and 2012 and collected information about 18 chronic neurologic conditions, including MS, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, stroke, epilepsy, and traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries. The survey included people aged 15 years and older living in the ten Canadian provinces who were diagnosed by a health professional as having one or more of the 18 chronic neurologic conditions included in the SLNCC. People who were excluded from the survey coverage represent less than 3% of the overall Canadian population, including persons living on reserves and other Aboriginal settlements, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, the institutionalized population, and persons living in the Quebec health regions of Région du Nunavik and Région des Terres-Cries-de-la-Baie-James. The SLNCC 2011/2012 response rate was high at 81.6%.28

The information collected in the SLNCC focused on Canadians' experience with chronic neurologic conditions, including effect on quality of life, work, and general well-being of people with these conditions. Moreover, the survey collected data on costs associated with chronic neurologic conditions, including productivity loss and out-of-pocket expenses. Furthermore, information related to assistance received from caregivers, including family members and friends, was included in the SLNCC. All the data were collected from people diagnosed as having chronic neurologic conditions or their proxies. Further details about the SLNCC are available from Statistics Canada (http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5182).

Study Variables

Outcome Measures

Employment Status. Employment status was categorized into currently working and not working.29 The not working category included both respondents who were not currently working because of MS and those permanently unable to work because of MS.

Informal Care. The frequency of informal assistance that people with MS received was categorized into three levels: none, less than daily, and requires daily assistance.29

Factors Assessed for Association with Outcomes

In addition to evaluating employment and informal care, we also wanted to explore what factors might be associated with each. Note that we are not trying to establish directionality because we are unable to do so with cross-sectional data. The following variables were hypothesized to be associated with employment and/or informal care in MS: sociodemographic variables (sex, age, and education), MS-related variables (age at first MS diagnosis, age at first MS symptoms, time since MS symptom onset, and time since MS diagnosis [disease duration]), health-related quality of life (HRQOL), self-reported general health, feelings of stigmatization, depression, and comorbidity. Health-related quality of life was quantified using Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3)30 (categorized into ≥0.7 [good quality of life] vs <0.7 [poor quality of life]). A score of less than 0.7 is considered an indicator of severe disability.31

A “feelings of stigmatization score” (referred to as stigma score henceforth) was calculated from the four questions answered on a 5-point Likert scale included in the SLNCC29: 1) because of my MS, some people seemed uncomfortable with me; 2) because of my MS, some people avoided me; 3) because of my MS, I felt left out of things; and 4) I felt embarrassed about my MS. Depression was categorized using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which scores depression based on the nine Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) criteria from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with a score of 10 or more indicating depression and less than 10 no depression.32,33 Comorbidity was derived from the chronic conditions included in the SLNCC and was dichotomized into no versus yes if a person with MS reported having at least one of the chronic conditions included in the SLNCC: heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes.

Analytical Sample

The analytical sample was restricted to the SLNCC respondents who reported a diagnosis of MS and provided valid responses to the outcomes and potentially associated factors included in the present study. It was noted that there were no systematic differences between the missing values and the observed values and, as such, the following analyses were undertaken on complete cases.34

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics included mean (standard deviation) or median (range) for continuous variables (eg, informal care) and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables (eg, employment status). The employment-related analyses were restricted to the population of working age (ie, MS respondents aged 18–65 years). To assess the factors associated with employment status and greater informal care requirements in patients with MS, unadjusted logistic regression models were fitted to investigate the association between each potential factor and employment status and informal care to see which factors passed an initial screening at α set to P = .2 as the model entry significance level. All potential factors independently associated with employment status and informal care (at an α level of 0.2) during bivariate analysis were retained for further exploration in the multivariable logistic regression models. Backward stepwise selection was used to select the most parsimonious models. At each step, models were also compared for the best fit using the Akaike information criterion and the Bayesian information criterion. Caregiver employment status (indirect work productivity loss) was analyzed only descriptively because the sample size was too small to allow model fitting, in accordance with the Statistics Canada confidentiality agreement regarding data release when a sample is small.

As the analysis progressed, we realized that employment status and informal care were both strongly associated with greater feelings of stigmatization; therefore, we elected to further explore potential factors associated with greater feelings of stigmatization in Canadians with MS. Using the stigma score, we categorized feelings of stigmatization into three levels (lower quartile score, 25th–75th percentile score, and upper quartile score). We constructed an unadjusted multinomial logistic regression and then retained potential factors associated with stigma (at P ≤ .2) for inclusion in the adjusted multinomial logistic regression. We used a backward stepwise selection approach to select the most parsimonious model of factors associated with stigma adjusting for sex, age, education, time since MS diagnosis, and comorbidity. For HRQOL, further analyses of HUI3 attributes were conducted to explore specific HUI3 attributes associated with employment status, greater informal care requirements, and greater feelings of stigmatization in people with MS.

The associations between the identified factors and employment status, informal care, and stigma are reported as odds ratios (ORs) and related 95% CIs. All statistical analyses were undertaken using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The SLNCC multistage cluster sampling design was accounted for in the analyses by applying the survey weights to account for uneven probabilities of selection and to provide population-based estimates and more precise estimates of variance around these point estimates.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the research ethics board of the University of British Columbia. Statistics Canada approved access to SLNCC data.

Results

Study Sample

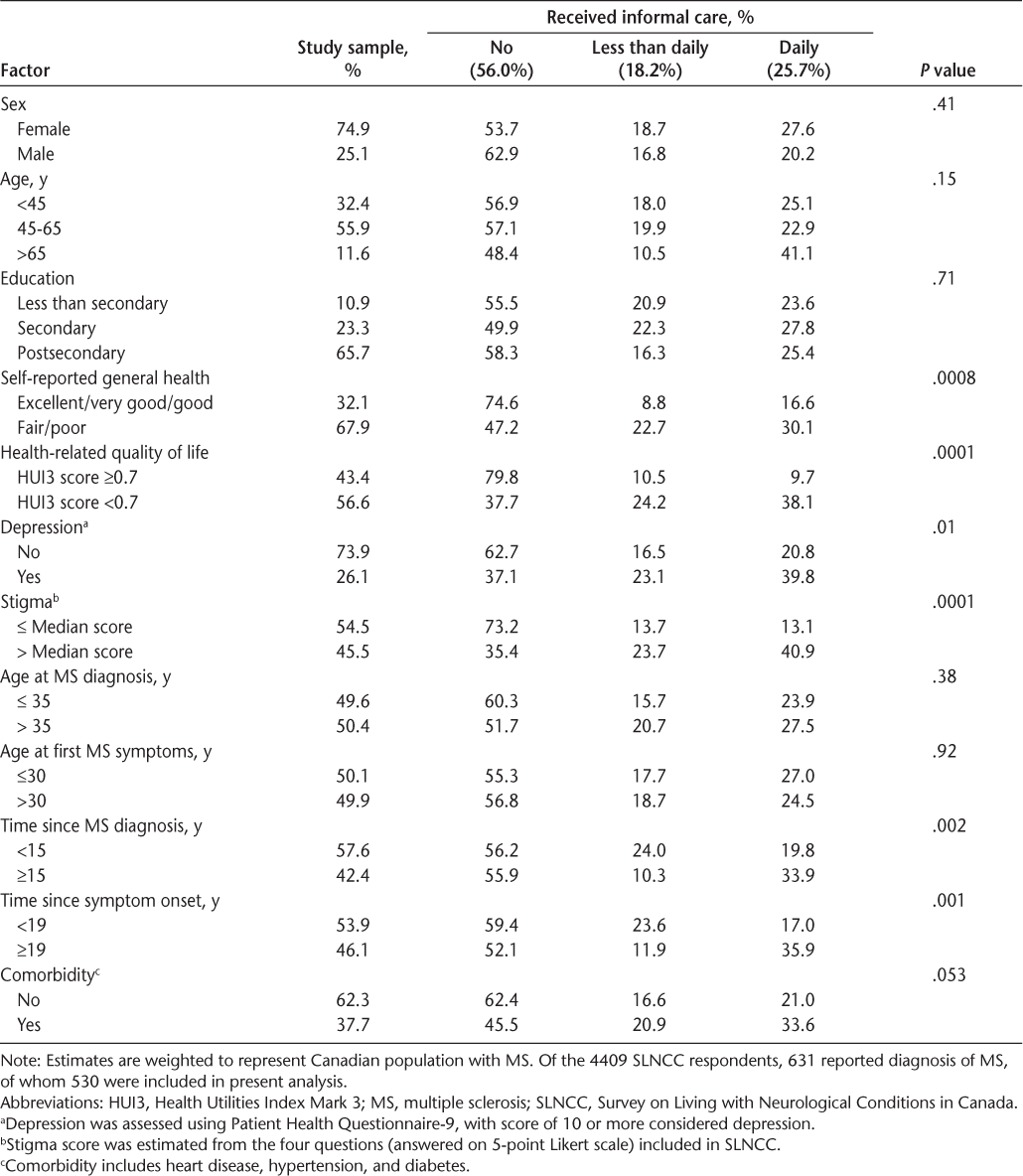

Of the 4409 SLNCC respondents, 631 reported a diagnosis of MS, of whom 530 were included in the analysis (Table 1). We excluded 101 respondents with MS because of missing data or invalid responses to the outcomes and/or potentially associated factors explored in this study. Most of the respondents included in the overall study sample were female (74.9%) and had postsecondary education (65.7%) (Table 1). The mean age of the respondents was 50.7 (95% CI, 49.0–52.4) years, reporting a mean age at first MS symptoms and at first MS diagnosis of 31.8 (95% CI, 30.2–33.4) years and 36.3 (95% CI, 34.8–37.8) years, respectively. On average, respondents reported living with MS symptoms for 18.9 (95% CI, 17.6–20.2) years and with an MS diagnosis for 14.4 (95% CI, 13.2–15.5) years. The mean difference in time between age at first MS symptoms (disease onset) and age at first MS diagnosis was approximately 4.5 (95% CI, 3.5–5.4) years, representing a potential delay in MS diagnosis. Most of the respondents (62.3%) did not report any comorbidities (Table 1). With respect to health status, 67.9% of respondents reported their general health as fair/poor, and 56.6% reported poor HRQOL (HUI3 score <0.7) (Table 1); however, self-reported general health was excluded from further analysis because it was found to be highly collinear with HRQOL scores. We found that 26.1% of the respondents were depressed, based on a score of 10 or greater on the PHQ-9 (Table 1).

Informal care in multiple sclerosis, SLNCC 2011/2012

Employment

Table S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org, reports the characteristics of the study sample by reported employment status. As described previously herein, note that the findings are based on an analysis restricted to the population of working age. Of 358 respondents aged 18 to 65 years, 47.8% were not working due to MS (Table S1). Regarding employment among caregivers, 15.5% reported reducing work and 8.2% reported stopping working altogether given their need to provide care.

Informal Care

Of the 44.0% of people with MS who reported receiving informal care, more than half required daily care (Table 1). Caregivers were mostly male (57.2%), the spouse or partner of someone with MS (64.1%), and living in the same household as someone with MS (66.1%). The mean age of caregivers was 52.0 (95% CI, 49.1–54.9) years, with most (81.6%) aged 18 to 65 years.

Stigma

Table S2 reports the characteristics of the study sample by reported feelings of stigmatization. Overall, 26.9% of the respondents were in the upper quartile of the stigmatization score (Table S2).

Factors Associated with Employment Status and Informal Care

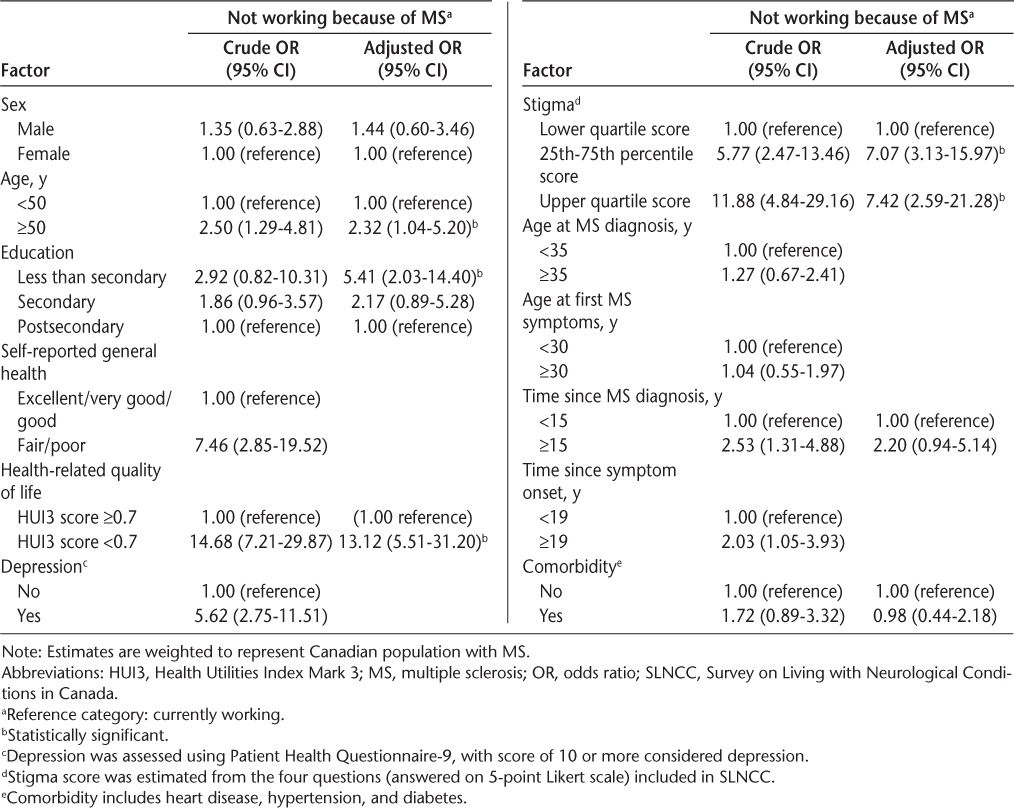

The odds of a person with MS reporting that they were not working was greater in respondents who reported greater feelings of stigmatization because of their MS (adjusted OR [aOR], 7.42 [95% CI, 2.59–21.28]) and poorer HRQOL (aOR, 13.12 [95% CI, 5.51–31.20]), adjusting for age, education, time since MS diagnosis, and comorbidity (Table 2). Exploring the specific domains of HRQOL further, people with MS who were more cognitively impaired (aOR, 1.96 [95% CI, 1.45–2.65]), who reported greater pain and discomfort (aOR, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.21–2.04]), and who were less mobile (aOR, 2.40 [95% CI, 1.82–3.18]) were more likely to report being unemployed, adjusting for sex, age, education, time since MS diagnosis, and comorbidity.

Factors associated with being unemployed in MS

With respect to disease duration, although respondents diagnosed as having MS for at least 15 years were more likely to be unemployed (aOR, 2.20 [95% CI, 0.95–5.14]) relative to those diagnosed less than 15 years previously, this association was not statistically significant (Table 2). Furthermore, having at least one comorbid condition was not associated with being unemployed in people with MS.

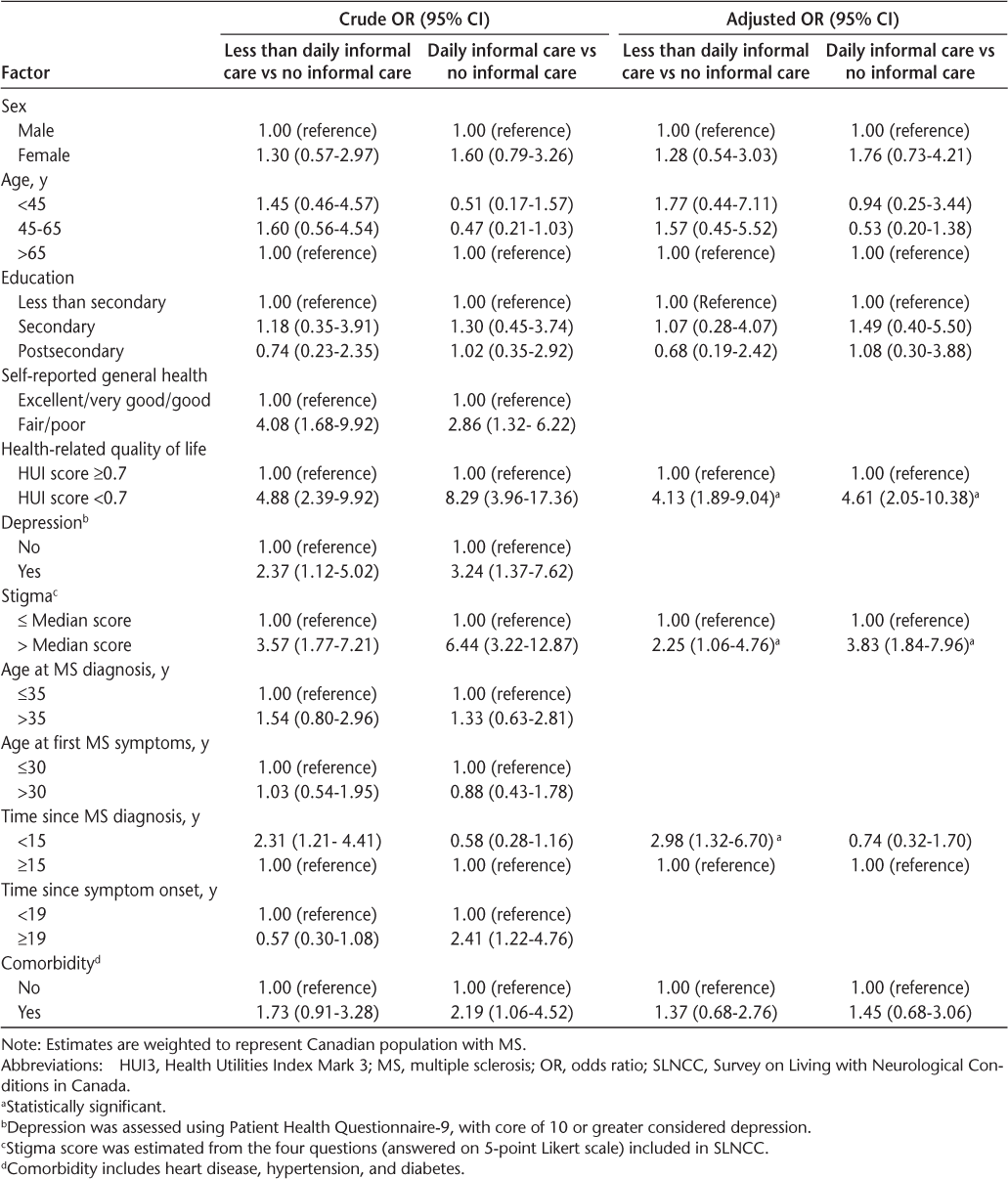

People with MS who reported greater feelings of stigmatization (aOR, 3.83 [95% CI, 1.84–7.96]) and poorer HRQOL (aOR, 4.61 [95% CI, 2.05–10.38]) were more likely to require informal care (which translates to greater caregiver burden), adjusting for sex, age, education, time since MS diagnosis, and comorbidity (Table 3). Similarly, people with MS who reported pain and discomfort (aOR, 1.34 [95% CI, 1.01–1.77]), impaired mobility (aOR, 1.36 [95% CI, 1.10–1.68]), and impaired dexterity (aOR, 1.77 [95% CI, 1.02–3.06]) were also more likely to require informal care, adjusting for sex, age, education, time since MS diagnosis, and comorbidity.

Factors associated with informal care requirements in MS

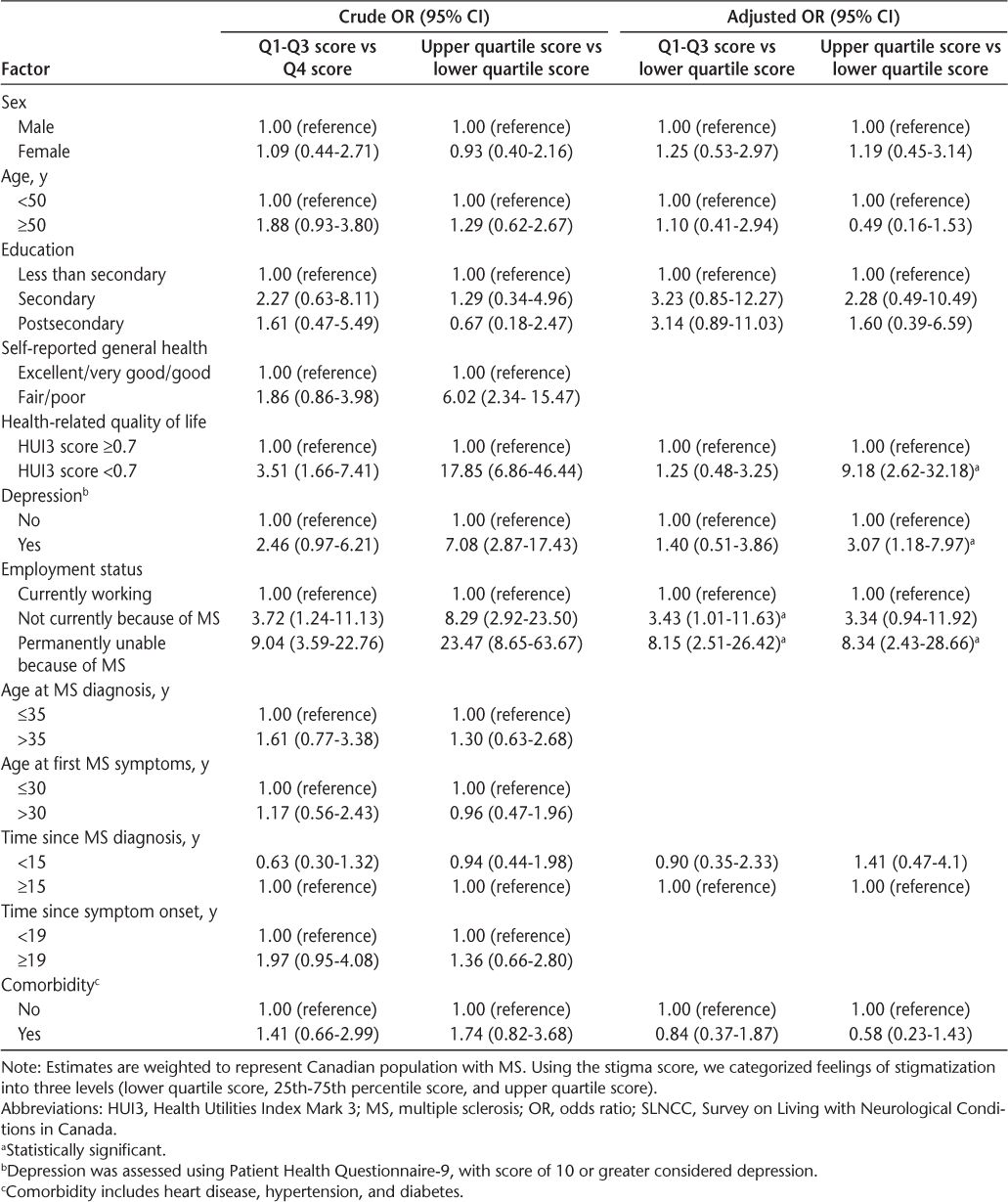

Factors Associated with Greater Feelings of Stigmatization

Compared with people with MS who reported fewer feelings of stigmatization because of their MS, respondents who reported greater feelings of stigmatization were more likely to be unable to work due to their MS (aOR, 8.34 [95% CI, 2.43–28.66]) and to report poorer HRQOL (HUI3 score <0.7) (aOR, 9.18 [95% CI, 2.62–32.18]) and depression (PHQ-9 score ≥10) (aOR, 3.07 [95% CI, 1.18–7.97]), adjusting for sex, age, education, time since MS diagnosis, and comorbidity (Table 4). Similarly, people with MS who reported greater feelings of stigmatization were more likely to be cognitively impaired and less mobile.

Factors associated with perceived stigma in MS

Discussion

The results of the present study suggest that MS has a substantial effect on being unemployed and is associated with considerable informal care requirement, which also results in additional lost productivity for caregivers—both of which contribute directly to the societal cost of MS, and potentially negatively to the psychological well-being of both people with MS and their caregivers. People with MS who feel stigmatized as a result of their MS and report a lower overall quality of life are also more likely to be unemployed and to require greater informal care. Furthermore, people with MS who report having pain and impaired mobility and dexterity are more likely to need more informal care, and those who report greater cognition and mobility impairment and pain are more likely to not be in the workforce.

Work productivity loss in MS (eg, absence from work, reduced hours of work, change in the type of work, and early retirement) has increasingly been recognized as one of the most significant burdens of MS.9–14,35–37 In the present study using a nationally representative population-based sample, we found that nearly half of the Canadians with MS aged 18 to 65 years were not in the workforce attributable directly to their MS. However, although there has been much interest in studying employment in people with MS, there is a paucity of research undertaken to understand the impact of MS on caregivers' employment/work productivity. In this study, we found evidence of productivity loss among caregivers because of needing to care for a relative or friend with MS, with nearly one in ten people caring for a person with MS stopping work altogether owing to a need to provide care.

As expected and consistent with previous studies,9,38–41 we found that sociodemographic factors, including increasing age and higher education attainment, were associated with unemployment in people with MS. However, the sex of the person with MS was not associated with unemployment. Note that the effect of sex on unemployment and work productivity loss among people with MS has not been consistently reported in previous studies.41–45 Furthermore, not unexpectedly, we found that poor HRQOL was strongly associated with unemployment in people with MS, and this has previously been reported.46 Although self-reported general health was not included in the present parsimonious model because it was collinear with HRQOL, we noted that poorer self-reported general health was strongly associated with not working due to MS when kept in the model and HRQOL was removed. This is consistent with previous research; for example, Krokavcova and colleagues45 found that patients with MS who were still in the workforce were less likely to report poor general health compared with those who were unemployed.

It has been suggested that the HRQOL of people with MS deteriorates when they leave the workforce,16 and, therefore, employment has been suggested as a potential public health intervention for people with MS.17 Exploring attributes or dimensions of HUI3 associated with employment status, we found that three (cognition impairment, physical disability [mobility impairment], and pain/discomfort) of eight attributes of HUI3 were strongly associated with not working due to MS. The present findings concur with previous studies that have found a higher likelihood of unemployment among people with MS who reported cognition impairment,38,41,47 physical disability,38–41,45 and pain.48 As such, interventions targeting these specific HRQOL attributes may contribute to improving the overall quality of life of people with MS and subsequently their work productivity. Regarding the association between employment status and time since MS diagnosis (disease duration), previous studies have found an inconsistent association.42,45 In the present study, we found that they are related but not significantly, likely reflecting that disease duration is not always a reflection of severity of disease and that disability has more of an effect on employability and work productivity than how long someone has had MS. Depression is prevalent in people with MS.49 Consistent with previous research, we found that depression was not associated with unemployment.9,35,50 However, Glanz and colleagues35 found that presenteeism was strongly associated with depression in patients with MS.

Although stigma has been suggested as a concern in chronic illness, there is a paucity of research undertaken to study stigma in MS.51,52 Evidence from previous research suggests that patients who feel stigmatized or anticipate stigma may conceal their disease and seek care less and, thus, are likely to experience a decreased quality of life.53,54 In the present study, we found that people with MS who reported greater feelings of stigmatization because of their MS were more likely to be unemployed and to require greater informal care, which also translates to effects on employment and work productivity in caregivers. Increased stigma was associated with being unemployed, even after adjusting for HRQOL, a surrogate for disease severity, thus indicating the independent relationship between stigma and unemployment. Therefore, it is important that we address the stigma issue, which might contribute to staying in the workforce and improve well-being.

Given the paucity of evidence in the current literature, we decided to perform a further analysis to explore potential factors associated with greater feelings of stigmatization in people with MS. We found that people with MS who were not working due to MS, who reported poor HRQOL, and who are depressed are more likely to report feeling stigmatized. Sociodemographic factors (age, sex, education), disease duration, and comorbidities were not found to be associated with greater feelings of stigmatization. Furthermore, we found increased odds of feelings of stigmatization in people with MS who reported impairment of cognition, emotion, and mobility (physical disability). As such, in addition to improving overall quality of life in people with MS, interventions targeting these specific HRQOL attributes may also contribute to reducing their feelings of stigmatization. Moreover, raising awareness of MS among the public might also help mitigate the stigma associated with MS.

In a UK population-based cross-sectional study, Mills and colleagues55 identified several factors associated with stigma, including depression, anxiety, and fatigue and increasing level of disability as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). In particular, people with MS who were in the workforce reported low feelings of stigma.55 Similarly, in a Greek cross-sectional study, Anagnostouli and colleagues56 also found disability and mental illness to be significant predictors of stigma in people with MS. They also found that stigma negatively affects quality of life for people with MS and functioning performances.56 Similar to Mills et al and Anagnostouli et al, the cross-sectional nature of the present study limits our understanding of the cause of stigma and employment status in MS. Feelings of stigmatization could occur because of low self-esteem caused by being out of work, negative thoughts surrounding aspects of the disease process (particularly if there is visible disability), loss of independence, and more reliance on caregiving, for example. Feelings of stigmatization could also lead someone to not disclose the extent of the disease and be less likely to ask for help or adaptation in the workplace, which could have kept them working longer. These feelings could also lead to seeking less formal care and relying more on caregivers emotionally and physically. Further research is needed to understand the nature and directionality of the relationship between stigma and employment status, work productivity loss, and caregiver burden.

The present findings suggest that nearly half of the respondents with MS required informal care and that partners/spouses of people with MS provided most of the informal care (64.1%). As described elsewhere, the frequency of informal care provided is associated with caregiver burden, which can lead to depression, anxiety, low HRQOL, and greater marital dissatisfaction.18–20,23 Furthermore, a variety of studies have also shown that caregiver burden may have a negative effect on people with MS (reciprocal effect) and the relationship between people with MS and their caregivers.19,21–23 Therefore, screening caregivers for early recognition of burden and how this might affect their health and well-being can help tailor interventions to improve caregiver health outcomes and work productivity and potentially mitigate the reciprocal caregiver burden effect. As described previously herein, caring for people with MS has a negative effect on employment status and work productivity among caregivers, and this has also been reported in previous studies.24,25 In this study, we did not specifically assess factors associated with work productivity loss among caregivers, independent of factors in people with MS, due to the small sample size; however, potential factors to explore include whether they are the sole caregiver, the type and location of their work, and their own health concerns.

The present study findings suggest several MS-related factors that were associated with a need for more informal care (a surrogate of caregiver burden in the present study), including feelings of stigmatization because of MS, poor HRQOL, and duration of MS. Consistent with previous studies,18,57 worse HRQOL was associated with greater informal care. This is not surprising given that HRQOL relates to disability in people with MS. In particular, in this study, HRQOL was quantified using HUI3, which has shown the best concordance with the EDSS across the full range of neurologic disability in MS compared with other measures of HRQOL (Short Form–6D and EQ-5D).58 Sociodemographic factors were not found to be associated with informal care requirements in people with MS. With respect to stigma, possible explanations could include 1) people with MS who feel stigmatized because of their MS may not seek formal care, which would result in worsening of the disease and, hence, greater informal care requirements; or 2) the more the MS progresses, the greater the feelings of stigmatization in people with MS and, hence, the association between stigma and caregiver burden. People who experience feelings of stigmatization may also develop low self-esteem, which may cause them to rely more on their caregivers. They may develop feelings of powerlessness and problems with their identity, which can contribute to increased need for emotional support and result in a sense of helplessness where they feel ill-equipped to manage on their own.

Although this study used data from a nationally representative sample, it has limitations that need to be acknowledged. The cross-sectional nature of the study limited our ability to make causal inferences. We analyzed data that were reported by people with MS or their proxies. As such, they may be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias. The survey high response rate (81.6%) makes a nonresponse bias (selection bias) that could limit the generalizability of the findings less likely. There are other relevant variables (eg, MS-related overall disability severity assessment [EDSS score]) that we could have examined that are not in the SLNCC.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that MS has a considerable effect on employment status of Canadians with MS and is associated with considerable informal care requirements and, consequently, additional productivity loss. Moreover, beyond the economic impact of the disease, people with MS also experience feelings of stigmatization, which has not been reported sufficiently in the literature. These findings suggest that feelings of stigmatization are an important component in how people with MS experience their disease and have important health, societal, and economic consequences. Identifying specific dimensions of HRQOL associated with greater informal care requirements is necessary for specific interventions to improve the quality of life of people with MS and to keep them in the workforce longer, which has great emotional and societal benefits for people with MS. As described previously herein, further research is needed to understand the nature and directionality of the relationship between stigma and employment status, productivity loss, and caregiver burden.

PRACTICE POINTS

MS has a substantial effect on unemployment and is associated with considerable informal care requirement, which also results in additional lost productivity for caregivers; both of these factors contribute directly to the societal cost of MS and potentially negatively to the psychological well-being of people with MS and their caregivers.

Feelings of stigmatization are an important component in how people with MS experience their disease, and they have important health, societal, and economic consequences.

People with MS who feel stigmatized because of their MS are more likely not to be working and to require greater informal care.

Acknowledgments:

The analysis presented in this article was conducted at the University of British Columbia Research Data Centre (UBC RDC), which is part of the Canadian Research Data Centre Network (CRDCN). The services and activities provided by the UBC RDC are made possible by the financial or in-kind support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Canadian Institute for Health Research, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, Statistics Canada, and the University of British Columbia.

References

Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas of MS 2013: Mapping Multiple Sclerosis Around the World. London, UK: Multiple Sclerosis International Federation; 2013.

Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada. About Multiple Sclerosis. 2015. https://mssociety.ca/about-ms. Accessed July 3, 2019.

Statistics Canada. Neurological conditions, by age group and sex, household population aged 0 and over, 2010/2011. In: Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2011.

Minagar A. Current and future therapies for multiple sclerosis. Scientifica. 2013;2013:249101.

Lynd LD, Traboulsee A, Marra CA, et al. Quantitative analysis of multiple sclerosis patients' preferences for drug treatment: a best–worst scaling study. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016;9:287–296.

Wingerchuk DM, Carter JL. Multiple sclerosis: current and emerging disease-modifying therapies and treatment strategies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:225–240.

Milo R, Miller A. Revised diagnostic criteria of multiple sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:518–524.

van der Hiele K, van Gorp DA, Heerings MA, et al. The MS@Work study: a 3-year prospective observational study on factors involved with work participation in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:134.

Moore P, Harding KE, Clarkson H, Pickersgill TP, Wardle M, Robertson NP. Demographic and clinical factors associated with changes in employment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1647–1654.

Ford DV, Jones KH, Middleton RM, et al. The feasibility of collecting information from people with multiple sclerosis for the UK MS Register via a web portal: characterising a cohort of people with MS. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:73.

Trisolini M, Honeycutt A, Wiener J, Lesesne S. Global Economic Impact of Multiple Sclerosis. London, UK: Multiple Sclerosis International Federation; 2010.

Palmer AJ, Colman S, O'Leary B, Taylor BV, Simmons RD. The economic impact of multiple sclerosis in Australia in 2010. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1640–1646.

Stawowczyk E, Malinowski KP, Kawalec P, Moćko P. The indirect costs of multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15:759–786.

Ernstsson O, Gyllensten H, Alexanderson K, Tinghög P, Friberg E, Norlund A. Cost of illness of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159129.

Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in The Netherlands. Eur J Health Econ. 2006;7:55–64.

Miller A, Dishon S. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the impact of disability, gender and employment status. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:259–271.

Chiu CY, Chan F, Edward Sharp S, Dutta A, Hartman E, Bezyak J. Employment as a health promotion intervention for persons with multiple sclerosis. Work. 2015;52:749–756.

Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Huang C. Caregiver burden among informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2011;13:76–83.

Gupta S, Goren A, Phillips AL, Stewart M. Self-reported burden among caregivers of patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2012;14:179–187.

Buhse M. Assessment of caregiver burden in families of persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;40:25–31.

Kleiboer AM, Kuijer RG, Hox JJ, Schreurs KM, Bensing JM. Receiving and providing support in couples dealing with multiple sclerosis: a diary study using an equity perspective. Personal Relationships. 2006;13:485–501.

Kleiboer AM, Kuijer RG, Hox JJ, Jongen PJ, Frequin ST, Bensing JM. Daily negative interactions and mood among patients and partners dealing with multiple sclerosis (MS): the moderating effects of emotional support. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:389–400.

Perrone KM, Gordon PA, Tschopp MK. Caregiver marital satisfaction when a spouse has multiple sclerosis. J Appl Rehabil Counsel. 2006;37:26.

Buchanan RJ, Huang C, Zheng Z. Factors affecting employment among informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2013;15:203–210.

McKenzie T, Quig ME, Tyry T, et al. Care partners and multiple sclerosis: differential effect on men and women. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:253–260.

Goverment of Canada. Mapping Connections: An Understanding of Neurological Conditions in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014.

Statistics Canada. Survey on Living with Neurological Conditions in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2012.

Bray GM, Strachan D, Tomlinson M, Bienek A, Pelletier C. Mapping connections: an understanding of neurological conditions in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/mapping-connections-understanding-neurological-conditions/mapping-connections-understanding-neurological-conditions-canada-11.html.

Statistics Canada. Survey on Living with Neurological Conditions in Canada (SLNCC) 2011–12. http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Instr.pl?Function=assembleInstr&a=1&&lang=en&Item_Id=114792#qb115624.

Horsman J, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G. The Health Utilities Index (HUI®): concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:54.

Feng Y, Bernier J, McIntosh C, Orpana H. Validation of disability categories derived from Health Utilities Index Mark 3 scores. Health Rep. 2009;20:43.

Kroencke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure [electronic version]. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–359.

Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393.

Glanz BI, Degano IR, Rintell DJ, Chitnis T, Weiner HL, Healy BC. Work productivity in relapsing multiple sclerosis: associations with disability, depression, fatigue, anxiety, cognition, and health-related quality of life. Value Health. 2012;15:1029–1035.

Roessler RT, Rumrill PD Jr. Multiple sclerosis and employment barriers: a systemic perspective on diagnosis and intervention. Work. 2003;21:17–23.

Schiavolin S, Leonardi M, Giovannetti AM, et al. Factors related to difficulties with employment in patients with multiple sclerosis: a review of 2002–2011 literature. Int J Rehabil Res. 2013;36:105–111.

Beatty WW, Blanco CR, Wilbanks SL, Paul RH, Hames KA. Demographic, clinical, and cognitive characteristics of multiple sclerosis patients who continue to work. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 1995;9:167–173.

Boe Lunde HM, Telstad W, Grytten N, et al. Employment among patients with multiple sclerosis: a population study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103317.

Krause I, Kern S, Horntrich A, Ziemssen T. Employment status in multiple sclerosis: impact of disease-specific and non-disease-specific factors. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1792–1799.

Salter A, Thomas N, Tyry T, Cutter G, Marrie RA. Employment and absenteeism in working-age persons with multiple sclerosis. J Med Econ. 2017;20:493–502.

Glad SB, Nyland H, Aarseth JH, Riise T, Myhr K-M. How long can you keep working with benign multiple sclerosis? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:78–82.

Simmons RD, Tribe KL, McDonald EA. Living with multiple sclerosis: longitudinal changes in employment and the importance of symptom management. J Neurol. 2010;257:926–936.

Rumrill PD Jr, Roessler RT, McMahon BT, Hennessey ML, Neath J. Gender as a differential indicator of the employment discrimination experiences of Americans with multiple sclerosis. Work. 2007;29:303–311.

Krokavcova M, Nagyova I, Van Dijk JP, et al. Self-rated health and employment status in patients with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:1742–1748.

Pack TG, Szirony GM, Kushner JD, Bellaw JR. Quality of life and employment in persons with multiple sclerosis. Work. 2014;49:281–287.

Rao SM, Leo GJ, Ellington L, Nauertz T, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis, II: impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology. 1991;41:692–696.

Shahrbanian S, Auais M, Duquette P, Andersen K, Mayo NE. Does pain in individuals with multiple sclerosis affect employment? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18:e94–e100.

Viner R, Fiest KM, Bulloch AG, et al. Point prevalence and correlates of depression in a national community sample with multiple sclerosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:352–354.

Smith MM, Arnett PA. Factors related to employment status changes in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:602–609.

Cadden MH, Arnett PA, Tyry TM, Cook JE. Judgment hurts: the psychological consequences of experiencing stigma in multiple sclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 2018;208:158–164.

Cook JE, Salter A, Stadler G. Identity concealment and chronic illness: a strategic choice. J Soc Issues. 2017;73:359–378.

Cook JE, Germano AL, Stadler G. An exploratory investigation of social stigma and concealment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2016;18:78–84.

Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. J Health Psychol. 2012;17:157–168.

Mills R, Eva Z, Tennant A, Young C. An assessment of felt-stigma in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21:619–620.

Anagnostouli M, Katsavos S, Artemiadis A, et al. Determinants of stigma in a cohort of Hellenic patients suffering from multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:101.

Forbes A, While A, Mathes L. Informal carer activities, carer burden and health status in multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21:563–575.

Fisk J, Brown M, Sketris I, Metz L, Murray T, Stadnyk K. A comparison of health utility measures for the evaluation of multiple sclerosis treatments. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:58–63.