Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Online Peer Support for People With Multiple Sclerosis: A Narrative Synthesis Systematic Review

Author(s):

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

People with multiple sclerosis often experience depression and anxiety, negatively affecting their quality of life, especially their social life. Peer support, whether in person or online, could improve social connection and coping. Online peer support allows people to engage from their home at a time that suits them. We sought to explore the benefits and challenges of online peer support and to identify successful elements of online peer support for people with multiple sclerosis.

METHODS

Using the narrative synthesis method, 6 databases were searched in April 2020 for articles published between 1989 and 2020; the search was updated in May 2022. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative research checklist and the Downs and Black checklist.

RESULTS

Of 10,987 unique articles identified through the database search, 11 were included. Benefits of online peer support included sharing information and experiences and emotional support. Successful elements included having a dedicated space to save information and the convenience of online peer support. Challenges included verification of information and the lack of nonverbal communication.

CONCLUSIONS

Online peer support can help those unable to access in-person support groups and can reduce the risk of social isolation. However, multiple sclerosis symptoms may make it difficult to use technological devices. Research is needed to further explore potential barriers to online peer support.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurodegenerative condition that causes damage to the central nervous system1 and significantly affects the lives of people who have it as well as their families.2 The number of people living with the disease is rising globally. In 2013 it was estimated that 2.3 million people were living with MS worldwide, which increased to 2.8 million people in 2020.3 People with MS experience cognitive changes, leading to difficulties processing and learning new information and solving problems.4 In addition, people with MS often experience depression and anxiety, increasing their risk for social isolation and loneliness.5 Physical symptoms of MS can include impaired mobility and balance, problems with bladder and bowel function, and sexual dysfunction. All symptoms affect a person’s family life (eg, becoming more dependent on family members for care),2,4 social life (eg, being unable to continue practicing hobbies or sports),6 and employment (eg, reducing work hours or leaving one’s job).7

Developing coping strategies to manage MS symptoms in daily life and to live well is important.8 This is in line with the social health framework: people can successfully adapt to living with a chronic health condition by focusing on coping strategies and abilities rather than disabilities.9 The social health framework has 3 dimensions: (1) ability to fulfill potential and obligations, (2) ability to manage life with some level of independence, and (3) ability to participate in social activities and work.9 Dröes et al10 analyzed the social health framework in dementia. They found that when focusing on the 3 dimensions of social health, and thus focusing on one’s strengths rather than limitations, people with dementia can still live meaningful, satisfying lives and experience a good quality of life.10

Fisher et al11 identified MS-related stress as a risk factor for depression and anxiety and that social support and engagement could lower levels of depression. Levin et al12 found that social networks have an important effect on physical functioning in people with MS: people with open networks have better physical functioning than those with close-knit (smaller) networks.12 One way to expand one’s social network, improve social support and engagement, and reduce the risk of isolation is through peer support.13 Peer support is an exchange of support between people who have a similar health condition or life experience.14 The importance of peer support for people with MS was highlighted by Russell et al,15 who suggest that it can lead to improved mental health outcomes. Moreover, peer support has the potential to support all 3 dimensions of social health.9 Peer support provides people with the opportunity to be part of a social network and build reciprocal relationships in which they can receive and provide support to others. This foundation of reciprocity can increase feelings of empowerment.14,16 Peers have a unique knowledge of what it is like to have MS and can share information and advice on coping. This makes peer support unique and irreplaceable by health care professionals, family members, or friends who do not have MS themselves.13 Nevertheless, McCabe et al17 found that many people living with MS do not currently have access to a peer support network, despite the known benefits of peer support.

Online peer support can be delivered in different ways via a variety of platforms (eg, discussion forums, social media), different modes of communication (eg, text-based, verbal, synchronous, asynchronous), and moderation (eg, peer moderators, professional moderators, no moderation).16,18 People with MS, particularly younger people, expressed the need for alternatives to traditional in-person support groups and an interest in online peer support (eg, Skype, email). Online support overcomes time constraints17 and geographical barriers.18 The review by Kingod et al13 shows that online peer support can be beneficial for people with chronic conditions, and research into online peer support for people affected by MS is growing as well (eg, Della Rosa and Sen19 and Lavorgna et al20). However, knowledge on the long-term effects of online peer support, how it affects users’ health and self-management, and what particular elements make it useful and meaningful need further research.18

This narrative synthesis systematic review explores the benefits and challenges of online peer support and identifies successful elements of online peer support for people with MS. Challenges are things that make it more difficult for a person with MS to use online peer support. Elements are labeled successful if the study identifies positive outcomes for the people with MS who are members of the online peer support platform and could be both human (eg, facilitator skills) and technological (eg, platform specific). The findings may provide more insight into how to improve existing, and develop new, online peer support opportunities for people with MS.

METHODS

Narrative Synthesis

This review follows the narrative synthesis procedures from Popay et al,21 which include the following elements: (1) development of the theory, (2) development of a preliminary synthesis, (3) exploration of relationships in the data, and (4) assessment of the robustness of the synthesis. This review also follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines.22

Search Strategy

A systematic database search was conducted in April 2020. The search was rerun in May 2022. The primary reviewer (E.V.G.) took the lead in developing the search strategy with the help of 2 librarians and another author (N.C.), who is an academic expert on online peer support. The initial search was part of a wider appraisal of the literature and included online peer support for people living with MS, Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Huntington disease. Six databases were searched: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Cochrane Library, Embase Medline, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science. The keywords used for the searches are presented in TABLE S1, available online at IJMSC.org. One search filter regarding year of publication (ie, 1989–2020) was applied.23 When rerunning the search, the filter was adjusted to the years 2020 to 2022. No filters were used for study design. Finally, the reference lists of the included papers were searched manually.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Papers were included if they met the following criteria:

The study population included people living with MS or a blend of people living with MS and caregivers.

The intervention included online peer support (ie, communication via the internet between peers in an online environment designed to facilitate social contact using asynchronous or synchronous text or text/video-based platform [eg, social media platforms, forums, chat rooms]).

Publication was between 1989 and 2020 for the first search and 2020 and 2022 for the follow-up search.

Publication was in a peer-reviewed journal.

Papers were excluded if they met the following criteria:

The study focused solely on caregiver perspectives.

The study included online peer support as part of an intervention that also included in-person or telephone-based peer support.

The study did not report on peer-to-peer interactions. This criterion was added after initial screening.

The identified paper was a literature review, opinion piece, protocol, editorial, or conference abstract.

The paper was written in a language other than English and a translation was not available.

Study Selection

EndNote (Clarivate Plc) was used to manage study selection. The primary reviewer (E.V.G.) performed the title, abstract, and full-text screening; E.V.G. contacted a second reviewer (A.R.L.) for studies that met the eligibility criteria but mostly focused on outcomes other than peer-to-peer support (eg, quality of life). A third reviewer (O.M.) was also consulted on this issue. The decision was made to add the eligibility criterion of reporting on peer-to-peer interactions. All included papers were assessed a second time against this new eligibility criterion.

Data Extraction

The primary reviewer E.V.G. used standardized data extraction forms for (1) study information, (2) study characteristics, (3) population characteristics, (4) characteristics of the online platform, (5) outcomes, and (6) implications for future research. Another researcher (A.R.L.) provided a second independent review of the completed data extraction forms.

Quality Assessment

The primary reviewer E.V.G. completed the initial quality assessment, and A.R.L. provided a second independent review. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist was used to assess qualitative studies.24 It has 10 items on “rigour, credibility and relevance.”25 The Downs and Black checklist was used for studies that could not be assessed by the CASP checklist. It consists of 27 items and is suitable for randomized and nonrandomized studies.26 Both quality checklists have been used in previous reviews (eg, McDermott et al27), and both are recommended by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination for reviews in health care.25

Studies that were assessed using the CASP checklist were labeled “high” quality if they met or partially met 8 to 10 items, “medium” quality if they met or partially met 5 to 7 items, and “low” quality if they met or partially met 0 to 4 items.28 Studies assessed using the Downs and Black checklist were graded “excellent” if they had 24 to 28 points, “good” if they had 19 to 23 points, “fair” with 14 to 18 points, and “poor” with less than 14 points.29

RESULTS

Preliminary Synthesis

An overview of the online database search, screening, and selection process is presented in FIGURE S1. The online database search returned 10,987 unique titles and abstracts. After screening the titles, abstracts, and texts, 8 studies met the inclusion criteria. The main reason studies were excluded in the first round of screening was that their focus was not online platforms being used for peer-to-peer interactions. The second database search resulted in 3 additional studies being included. Hand searching the reference lists of the included papers did not result in additional papers being included.

Study Characteristics

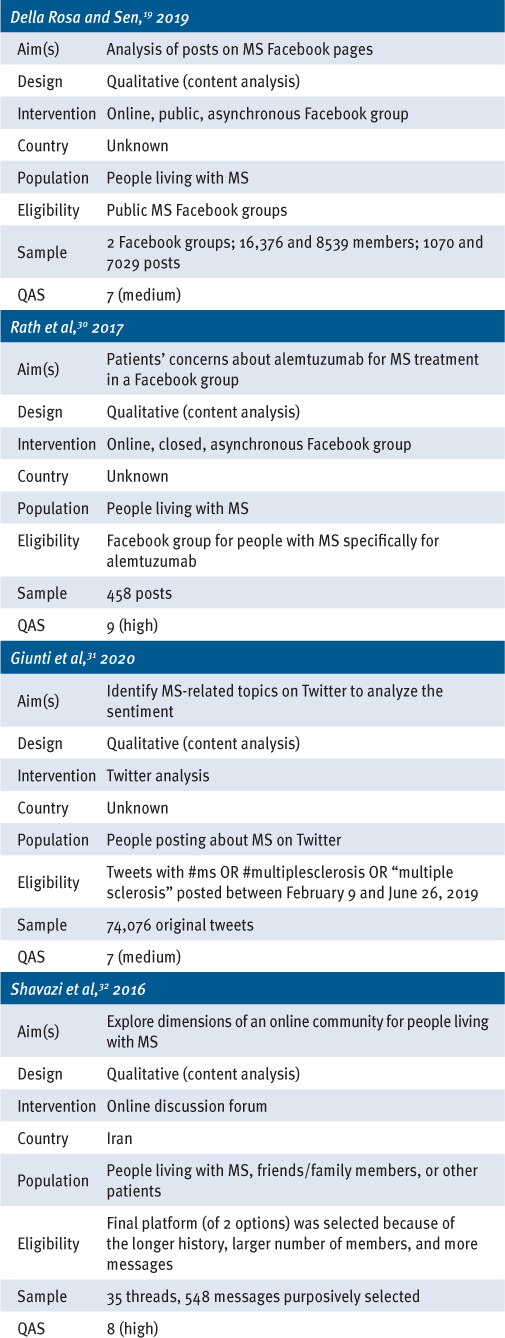

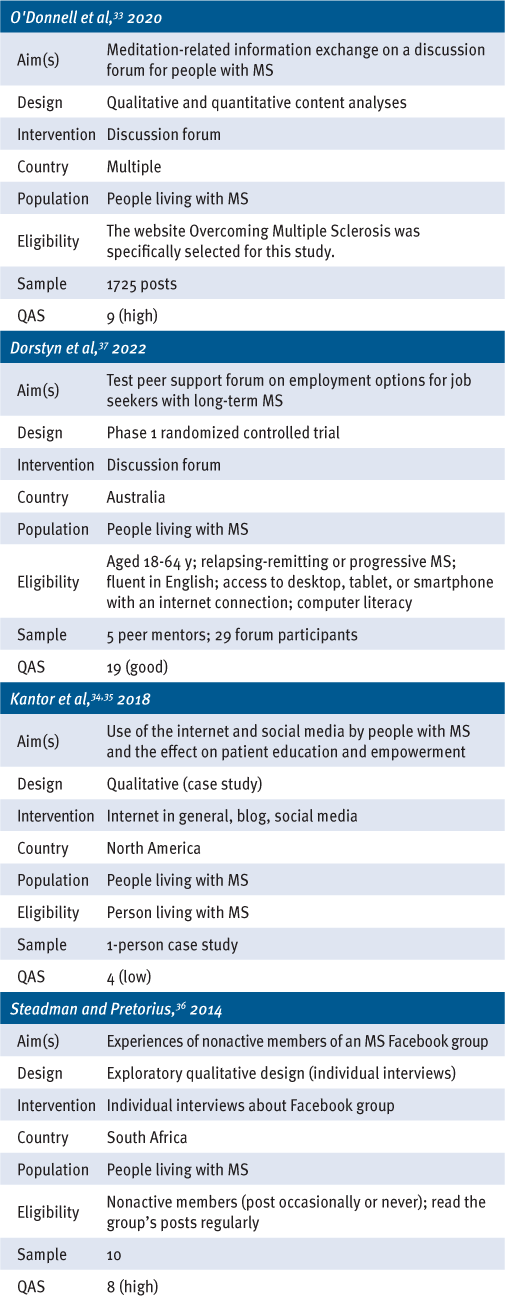

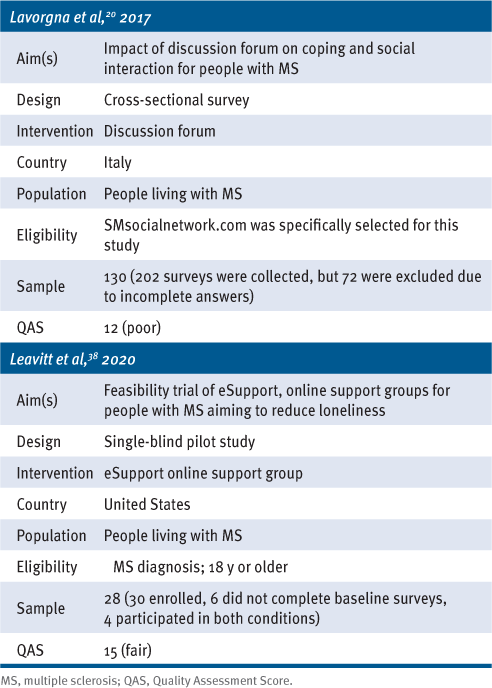

Five studies used a qualitative content analysis. Della Rosa and Sen19 and Rath et al30 analyzed posts in a Facebook group. Giunti et al31 analyzed Twitter posts, and Shavazi et al32 and O’Donnell et al33 analyzed posts on a discussion forum. Other methods included a case study,34,35 individual interviews,36 a cross-sectional survey,20 a randomized controlled trial,37 and a pilot study.38 A fuller description of the study characteristics is provided in TABLE 1.

Study Characteristics and Summary of Interventions

(continued)

(continued)

Summary of Interventions

All but 1 study included text-based, asynchronous (not in real time) communication. In the study by Leavitt et al,38 participants communicated verbally in real time. The online peer support communities analyzed by Della Rosa and Sen,19 Rath et al,30 Dorstyn et al,37 O’Donnell et al,33 Steadman and Pretorius,36 Lavorgna et al,20 and Leavitt et al38 were moderated: 1 or multiple people monitored the group and the posts being shared or guided the discussion. In the studies by Kantor et al,34,35 participants spoke about online peer support in general rather than a specific platform, and, thus, moderation was not discussed. Whether the platform was moderated in the study by Shavazi et al32 is unknown. Shavazi et al32 included family members and friends, whereas the other studies included only people with MS. A fuller description of the interventions is provided in Table 1.

Quality Assessment

An overview of the CASP and Downs and Black checklists and the scores for each study are presented in TABLE S2 and TABLE S3. Eight papers were assessed using the CASP checklist: 4 were high quality,30,32,33,36 2 medium quality,19,31 and 2 poor quality.34,35 Three papers were assessed using the Downs and Black checklist: 1 was labeled as good,37 1 as fair,38 and 1 as poor.20

Key Findings

An overview of the key findings is presented in TABLE S4. Social support was the most evident benefit and successful element of online peer support, with informational, network, and emotional support provided.

Benefits and Successful Elements of Online Peer Support

Informational Support

The most frequently addressed benefit of online peer support in this review was informational support.19,20,30,32–37 Through the online platforms, people with MS shared information on and experiences with medication and treatments and coping strategies for challenges faced in daily life. Online peer support provided an opportunity to learn while also sharing information and helping others, which can increase feelings of empowerment. This included factual or medical as well as experiential information, for example about certain medications or treatments.

“I posted that I was about to start taking it [antidepressant] and wondered about things like dependency and mood changes. Almost instantly others from around the world were commenting and sharing their experiences, giving me the feedback I needed to make my own decision.” 34

Steadman and Pretorius36 analyzed the experiences of nonactive members of an MS Facebook group. They found that despite not being actively involved in the discussions, these members still received informational support because they could read the messages of others.

“There are lot of people that have been having MS for 10, 20 years, and I’ve just had it for 6 years now, so my knowledge of this is not that good, so I prefer the older members to actually give that kind of answers.” 36

A successful component of online peer support platforms is making information easy to find. The platforms analyzed by Rath et al30 and Shavazi et al32 had dedicated sections where frequently asked questions and resources were saved. Dorstyn et al37 and O’Donnell et al33 found that discussion forums can be a useful platform to share and store a variety of resources, including audiovisual resources. Steadman and Pretorius36 showed that participants appreciated the information being shared in the Facebook group and that they perceived it as reliable and good quality. They mentioned that the advantage of it being online was that there is a large body of information that is always available and updated.

Network Support

The second most frequently mentioned benefit of online peer support is having a network to exchange support.20,32,34–36,38 Despite not being physically close, people with MS who participated in online peer support communities reported feeling connected with the other members, experienced a sense of community, and built friendships. Steadman and Pretorius36 showed that this was also true for some nonactive members.

“I will always go on there and read the messages, it is like my family; it’s like real close friends even though I’m not in a personal way close to them.” 36

What made online peer support particularly beneficial was that support was available when needed. Furthermore, Leavitt et al38 showed that online peer support can be a safe and convenient way to be involved in peer support because participants do not need to travel, allowing people from remote areas to take part as well.

“Of the support groups I’ve been in, this one feels the most intimate. Joining from my home makes me feel very safe.” 38

Emotional Support

Kantor et al,34,35 Leavitt et al,38 Shavazi et al,32 O’Donnell et al,33 and Steadman and Pretorius36 reported on emotional support, with online platforms as a place for bonding and sharing mutual understanding and empathy, despite members not being physically close. On text-based platforms such as social media and discussion forums, emoticons can be a way to express emotions and affections online.32 By sharing personal experiences, members shared words of encouragement, hope, and reassurance. Moreover, being able to share this connection with others can give people hope and purpose in their lives.35

“Don’t worry, my problems also began with pain in my eyes, blurred vision.... I also was very worried about losing my eyesight forever.… Don’t stress yourself, and don’t think about it. I regained my eyesight and I don’t have any problems now, but it takes some time.” 32

Challenges of Online Peer Support

Although access to a wide range of information can be a benefit of online peer support, the amount of information can be overwhelming, and people may share posts that are not in line with the purpose of the group.36 Furthermore, it is not always possible to verify the information’s trustworthiness.34,35 These issues can be solved by having clear guidelines on the purpose of the group and group moderators.30 In addition, having professionals provide information could improve the trustworthiness.36

The lack of nonverbal communication, such as body language and facial expressions, can be a limitation of online peer support in text-based platforms, as people may experience a lack of emotional connection and may not always feel comfortable sharing their experiences with the group.36 Although Leavitt et al38 reported findings of an online peer support intervention using video meetings, they did not report on the particular benefits or challenges of using video meetings as the mode of communication.

Finally, MS symptoms can limit one’s ability to use the computer and can be a barrier to online peer support access. Steadman and Pretorius36 found that members with a nonactive status at times experienced difficulties socializing, as other members of the group did not always reach out or keep in contact. Furthermore, understanding privacy on social media can be a challenge for anyone, for example knowing who can and cannot see your posts.35

DISCUSSION

Principal Results

The findings show that through online peer support, people with MS can exchange information and ways of coping with MS symptoms, as well as emotional support. This can improve all dimensions of the social health framework for people with MS.

Benefits and Successful Elements of Online Peer Support

This review demonstrates that benefits of peer support can go beyond in-person settings and can be present in online communities as well. People with MS frequently use online communities for informational support. People can gather information through online resources and personal experiences of others, including experiences with medications. These findings are supported by Loane and D’Alessandro,39 who researched online peer support for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. They found that people often started a conversation by asking for information, and that often lead to others sharing personal experiences and exchanging emotional support.39 An advantage of online peer support is that threads, discussion topics, or information can be archived or saved. The asynchronous and text-based nature allow people to revisit different threads or topics when they want access to the information. Another benefit of online peer support communities is that they are typically much larger in size than in-person groups, offering a much wider and heterogeneous pool of people to exchange support with and to learn from.30,32,36 Learning from others can help in developing and improving coping skills to live well with MS, meeting the first and second dimensions of the social health framework: ability to fulfill potential and obligations and to manage life with some level of independence.9 Finally, the anonymous nature of some platforms may make it easier for people to discuss certain topics that they would not feel comfortable discussing in person, such as relationships and sexuality.40,41

This review also shows that people with MS can experience social connection, mutual understanding, and friendship in online peer support communities, fulfilling the third dimension of the social health framework: ability to participate in social activities and work.9 Although not being physically close, people were able to express emotions, including through emoticons.32 This is similar to findings on online peer support for people with Parkinson disease.42 Steadman and Pretorius36 found that even nonactive members of a Facebook group felt connected, and Davis and Boellstorff43 found that online peer support could be particularly helpful for people who live in rural areas. The opportunity to join from the comfort of one’s own home is unique.

In the United Kingdom, 92% of the adult population uses the internet.44 During the COVID-19 pandemic, videoconferencing platforms, such as Zoom and MS Teams, became more popular and allowed people to access health and social care services.

Challenges of Online Peer Support

First, although internet use and access are common, this differs, with some people having reduced or no access to the internet, particularly in rural areas.45 Even with internet access, people need modern digital devices and a strong and stable internet connection; because these are not accessible to everyone, some miss out on the benefits of online support services.46

Second, the amount of information on the internet can feel overwhelming,36 and it can be difficult to assess the trustworthiness of online resources.34,35 Research shows that social media platforms can be a source of misinformation.47 In addition, learning about the progression of MS and the severity of symptoms from informational resources or the experiences of others can be distressing. Moderators can monitor the platform for misinformation and remove harmful or misleading posts, keeping the community a safe space for everyone.40,48 Without moderators there is not a dedicated person to provide resources and to check in on members should there be a concern for or risk of significant emotional distress or self-harm. Moderators can also remind people to always consult with their physician regarding treatment or medication. Having professionals share information or review the resources that are being shared may further reduce concerns around trustworthiness.36

Third, people may have concerns regarding privacy and security when interacting with others in an online setting because there is often a lack of personal information due to the open nature of such platforms. This makes it difficult for people to identify the level of similarity with other group members, for example in age or time since diagnosis, which is one of the key aspects of peer support.14 The importance of similarity was also identified by Garabedian et al,49 who found that for people who are newly diagnosed as having MS, a support group with people who are in a more advanced stage of the disease can be a negative experience. Unwanted exposure to the negative aspects of a condition is a common problem of online peer support.50,51

Finally, the anonymous nature of some online forums may result in people feeling a lack of connection with other group members, feeling unsure whether they can trust others,35 and leaving the group for these or other reasons. Even with moderators, follow-up with those who leave may be difficult. Leavitt et al38 focused on peer support through video meetings, which could potentially reduce the anonymity; however, they did not report on the particular benefits or challenges of video meetings as the mode of communication.

Limitations

Online peer support can be provided via a variety of online platforms, including text-based and verbal communication; however, the systematic database search identified only 1 study38 focusing on verbal communication. In addition, only 2 studies discussed potential barriers and challenges.34–36 Therefore, this review may overrepresent the positives of online peer support and not provide enough insights into potential negatives. This is a common limitation of research into online peer support.42 Finally, physical symptoms associated with MS may limit access to online peer support. Although 1 study mentioned this issue,36 this review does not include the perspectives of those who cannot or do not want to use online peer support.

Recommendations for Future Research

During the COVID-19 pandemic videoconferencing platforms such as Zoom and MS Teams became more popular, but the update of the database searches in May 2022 did not identify any studies of peer support via videoconferencing platforms. Because it is verbal communication in real time, and includes a face-to-face option, video peer support differs from text-based peer support. Although this review included 1 study on peer support through video meetings,38 it does not detail how people experienced the video element. Future research could explore whether people with MS are using videoconferencing platforms for peer support and, if so, what their experiences are. Additional exploratory research could include outcome measurements related to mental health and link to previous research on the impact of social support on mental health outcomes such as depression and anxiety.11

Because MS symptoms may make it difficult for some people to use digital devices,36 future research could explore whether certain platforms are easier to use or whether other technology might help, such as voice assistive tools similar to those used by people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.52 Another research avenue would be to explore the experiences and views of those with MS who cannot or do not want to use online peer support, what barriers they face, and how they might be overcome. Qualitative or mixed-methods research using interviews or surveys could explore people’s experiences and needs.

CONCLUSIONS

Peer support can be a way for people with MS to stay socially connected and reduce their risk of loneliness and social isolation by sharing their experiences and learning from others, including developing coping strategies. Online peer support offers many benefits, including improved accessibility to support. Moreover, even simply reading about others’ experiences can already make people feel supported and help with developing coping skills. Through online platforms, information can be archived as well as constantly updated. On the other hand, online peer support also has challenges that should be addressed or understood. People should be cautious when interpreting information that they find online and should always consult with their doctor regarding medication and symptoms. Physical MS symptoms may hinder some people from using the technology needed to access online peer support. Future research is needed to further explore the barriers to online peer support for people with MS and how to overcome them.

PRACTICE POINTS

» Peer support can improve social connection and coping for people living with multiple sclerosis.

» Online peer support overcomes geographical barriers, which can be helpful for people whose symptoms make it difficult to travel to in-person support groups.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

We thank Emma Young, deputy head of Library and Knowledge Services, and Naomi Thorpe, senior information specialist from Library and Knowledge Services, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, for their support in defining the search strategy and running the pilot searches for this review.

References

What is MS? Multiple Sclerosis Trust. Updated April 2022. Accessed June 14, 2022.https://mstrust.org.uk/about-ms/what-ms/ms-facts

Holland NJ, Schneider DM, Rapp R, Kalb RC. Meeting the needs of people with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, their families, and the healthcare community. Int J MS Care. 2011; 13(2): 65–74. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073-13.2.65

The Atlas of MS. Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Accessed June 14, 2022.https://www.atlasofms.org/map/global/epidemiology/number-of-people-with-ms

MS signs & symptoms. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Accessed June 14, 2022.https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis/MS-Symptoms

Al-Asmi A, Al-Rawahi S, Al-Moqbali ZS, . Magnitude and concurrence of anxiety and depression among attendees with multiple sclerosis at a tertiary care hospital in Oman. BMC Neurol. 2015; 15: 131. doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0370-9

Cowan CK, Pierson JM, Leggat SG. Psychosocial aspects of the lived experience of multiple sclerosis: personal perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2020; 42(3): 349–359. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1498545

Strober LB, Chiaravalloti N, DeLuca J. Should I stay or should I go? a prospective investigation examining individual factors impacting employment status among individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS). Work. 2018; 59(1): 39–47. doi: 10.3233/WOR-172667

Topcu G, Griffiths H, Bale C, . Psychosocial adjustment to multiple sclerosis diagnosis: a meta-review of systematic reviews. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020; 82: 101923. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101923

Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, . How should we define health? BMJ . 2011; 343: d4163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4163

Dröes RM, Chattat R, Diaz A, . Social health and dementia: a European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging Ment Health. 2017; 21(1): 4–17. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1254596

Fisher PL, Salmon P, Heffer-Rahn P, Huntley C, Reilly J, Cherry MG. Predictors of emotional distress in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Affect Disord. 2020; 276: 752– 764. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.073

Levin SN, Riley CS, Dhand A, . Association of social network structure and physical function in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2020; 95(11): e1565–e1574. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010460

Kingod N, Cleal B, Wahlberg A, Husted GR. Online peer-to-peer communities in the daily lives of people with chronic illness: a qualitative systematic review. Qual Health Res. 2017; 27(1): 89–99. doi: 10.1177/1049732316680203

Keyes SE, Clarke CL, Wilkinson H, . “We’re all thrown in the same boat …”: a qualitative analysis of peer support in dementia care. Dementia (London). 2016; 15(4): 560–577. doi: 10.1177/1471301214529575

Russell RD, Black LJ, Pham NM, Begley A. The effectiveness of emotional wellness programs on mental health outcomes for adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020; 44: 102171. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102171

Barak A, Boniel-Nissim M, Suler J. Fostering empowerment in online support groups. Comput Human Behav. 2008; 24( 5):1867–1883. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2008.02.004

McCabe MP, Ebacioni KJ, Simmons R, McDonald E, Melton L. Unmet education, psychological and peer support needs of people with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2015; 78(1): 82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.05.010

Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, Carroll JK, Irwin A, Hoving C. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013; 15(4): e85. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1933

Della Rosa S, Sen F. Health topics on Facebook groups: content analysis of posts in multiple sclerosis communities. Interact J Med Res. 2019; 8( 1): e10146. doi: 10.2196/10146

Lavorgna L, Russo A, De Stefano M, . Health-related coping and social interaction in people with multiple sclerosis supported by a social network: pilot study with a new methodological approach. Interact J Med Res. 2017; 6( 2):e10. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.7402

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, . Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews . Lancaster University; 2006.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021; 88: 105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Jacksi K, Abass SM. Development history of the world wide web. Int J Sci Technol Res. 2019; 8(9):75– 79.

CASP Checklists. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Accessed June 14, 2022.https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. University of York; 2009.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998; 52(6): 377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377

McDermott O, Crellin N, Ridder HM, Orrell M. Music therapy in dementia: a narrative synthesis systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013; 28(8): 781–794. doi: 10.1002/gps.3895

Bayliss A, Currie L, McIntosh T, . Infusion Therapy Standards: Rapid Evidence Review. Royal College of Nursing; 2016.

O’Connor SR, Tully MA, Ryan B, Bradley JM, Baxter GD, McDonough SM. Failure of a numerical quality assessment scale to identify potential risk of bias in a systematic review: a comparison study. BMC Res Notes. 2015; 8: 224. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1181-1

Rath L, Vijiaratnam N, Skibina O. Alemtuzumab in multiple sclerosis: lessons from social media in enhancing patient care. Int J MS Care. 2017; 19(6): 323–328. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2017-010

Giunti G, Claes M, Dorronzoro Zubiete E, Rivera-Romero O, Gabarron E. Analysing sentiment and topics related to multiple sclerosis on Twitter. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2020; 270: 911–915. doi: 10.3233/SHTI200294

Shavazi MA, Morowatisharifabad MA, Shavazi MT, Mirzaei M, Ardekani AM. Online social support for patients with multiple sclerosis: a thematic analysis of messages posted to a virtual support community. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2016; 4(3): 188–198.

O’Donnell JM, Jelinek GA, Gray KM, . Therapeutic utilization of meditation resources by people with multiple sclerosis: insights from an online patient discussion forum. Inform Health Soc Care. 2020; 45(4): 374–384. doi: 10.1080/17538157.2020.1755975

Kantor D, Bright JR, Burtchell J. Perspectives from the patient and the healthcare professional in multiple sclerosis: social media and patient education. Neurol Ther. 2018; 7(1): 23–36. doi: 10.1007/s40120-017-0087-3

Kantor D, Bright JR, Burtchell J. Perspectives from the patient and the healthcare professional in multiple sclerosis: social media and participatory medicine. Neurol Ther. 2018; 7(1): 37–49. doi: 10.1007/s40120-017-0088-2

Steadman J, Pretorius C. The impact of an online Facebook support group for people with multiple sclerosis on non-active users. Afr J Disabil. 2014; 3(1): 132. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v3i1.132

Dorstyn D, Oxlad M, Roberts R, . MS JobSeek: a pilot randomized controlled trial of an online peer discussion forum for job-seekers with multiple sclerosis. J Vocat Rehabil. 2022; 56: 81– 91. doi: 10.3233/JVR-211174

Leavitt VM, Riley CS, De Jager PL, Bloom S. eSupport: feasibility trial of telehealth support group participation to reduce loneliness in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2020; 26( 13): 1797– 1800. doi: 10.1177/1352458519884241

Loane SS, D’Alessandro S. Communication that changes lives: social support within an online health community for ALS. Commun Q. 2013; 61(2): 236–251. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2012.752397

Gatos D, Günay A, Kırlangıç G, Kuscu K, Yantac AE. How HCI bridges health and design in online health communities: a systematic review. Presented at: Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2021; June 28–July 2, 2021; Virtual event. doi: 10.1145/3461778.3462100

Lieberman MA, Winzelberg A, Golant M, . Online support groups for Parkinson’s patients: a pilot study of effectiveness. Soc Work Health Care. 2005; 42(2): 23–38. doi: 10.1300/J010v42n02_02

Gerritzen EV, Lee AR, McDermott O, Coulson N, Orrell M. Online peer support for people with Parkinson disease: narrative synthesis systematic review. JMIR Aging. 2022; 5(3): e35425. doi: 10.2196/35425

Davis DZ, Boellstorff T. Compulsive creativity: virtual worlds, disability, and digital capital. Int J Comm. 2016; 10: 2096–2118.

Internet users UK: 2020: measuring the data. Office for National Statistics. Updated April 6, 2021. Accessed June 14, 2022.https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/itandinternetindustry/bulletins/internetusers/2020#measuring-the-data

United Kingdom. Internet World Stats. Accessed June 14, 2022.https://www.internetworldstats.com/europa2.htm#uk

Watts G. COVID-19 and the digital divide in the UK. Lancet Digit Health. 2020; 2( 8): e395– e396. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30169-2.

Wang Y, McKee M, Torbica A, Stuckler D. Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Soc Sci Med. 2019; 240: 112552. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112552

Perry A, Pyle D, Lamont-Mills A, du Plessis C, du Preez J. Suicidal behaviours and moderator support in online health communities: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021; 11( 6): e047905. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047905

Garabedian M, Perrone E, Pileggi C, Zimmerman V. Support group participation: effect on perceptions of patients with newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2020; 22(3): 115–121. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2018-099

Coulson NS. How do online patient support communities affect the experience of inflammatory bowel disease? an online survey. JRSM Short Rep. 2013; 4(8): 2042533313478004. doi: 10.1177/2042533313478004

Holbrey S, Coulson NS. A qualitative investigation of the impact of peer to peer online support for women living with polycystic ovary syndrome. BMC Womens Health. 2013; 13: 51. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-51

Caron J, Light J. “My world has expanded even though I’m stuck at home”: experiences of individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis who use augmentative and alternative communication and social media. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2015; 24(4): 680–695. doi: 10.1044/2015_AJSLP-15-0010

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This research was performed as part of the Marie Curie Innovative Training Network action, H2020-MSCA-ITN-2018 (grant agreement 813196).