Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

A Qualitative, Multiperspective Inquiry of Multiple Sclerosis Telemedicine in the United States

Author(s):

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Telemedicine has expanded access to high-quality, appropriate, and affordable health care for people with multiple sclerosis (MS). This study explored how the expansion of MS telemedicine is perceived and experienced by people with MS, health care providers (HCPs), and payers and policy experts (PYs).

METHODS

Forty-five semistructured interviews with 20 individuals with MS, 15 HCPs, and 10 PYs were conducted between September 2020 and January 2021. The interviews were recorded on a televideo platform, transcribed, and analyzed for themes using qualitative data software.

RESULTS

Interviews revealed the following 4 themes. Technology: Telemedicine increases access and convenience. Technical challenges were the most cited downside to telemedicine. Clinical encounters: Confidence in MS care via telemedicine varies. Virtual “house calls” have clinical benefits. Financing and infrastructure: Reimbursement parity is critical to utilization and expansion of telemedicine. Stakeholders are hopeful and fearful as infrastructure and business models begin to shift. Shifting expectations: The familiar structure of the office visit is currently absent in telemedicine. Telemedicine visits need more intentionality from both providers and patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Telemedicine is an efficient, convenient way to deliver and receive many aspects of MS care. To expand telemedicine care, many HCPs need more training and experience, people with MS need guidance to optimize their care, and PYs in the United States need to pass legislation and adjust business models to incorporate benefits and reimbursement for telemedicine health in insurance plans. The future is promising for the ongoing use of telemedicine to improve MS care, and stakeholders should work to preserve and expand the policy changes made during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) affects more than 2.8 million people worldwide1 and is the most common neurodegenerative disease in young adults. It can produce a variety of neurologic deficits that impair mobility, making it difficult for people with MS to access health care. Additional barriers to accessing care include distance from health care providers (HCPs); costs of services, medication, and transportation; and inadequate health insurance coverage and reimbursement.2–4 A 2007 study found that, in the United States, at least 31% of people with MS were unable to access the specialists their physician recommended they see.5 We anticipate that with the advent of high-speed internet, inexpensive cameras, and monitoring software, telemedicine will continue to fill some of these gaps in care access for people with MS.6,7

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic produced multiple challenges for health systems throughout the world.8 Among them was the provision of specialty care for patients with chronic conditions such as MS.9–11 To prevent the spread of COVID-19, face-to-face visits were either deferred or converted to telemedicine visits within weeks.12,13 This dramatic shift in care forced both providers and people with MS to learn new ways to communicate. Private health care insurance programs followed the lead of Medicare to cover and fully reimburse telemedicine visits and to relax security requirements for patient-provider communication and within-state licensing and liability requirements for HCPs.14,15 The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of people with MS, HCPs, and payers and policy experts (PYs) on the use of telemedicine for the provision of MS care.

METHODS

Qualitative research methods have been effectively used to explore telemedicine practice and processes from diverse perspectives.16 We conducted semistructured interviews between September 2020 and January 2021 to explore telemedicine practice and experiences among people with MS, HCPs, and PYs.7,17 Approval for this study was granted by the institutional review board of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center-Washington, DC.

Recruitment

People with MS were purposefully selected and stratified by race and ethnicity, sex, US census region, and disability (Expanded Disability Status Scale scores)18 to generally reflect the US MS population.1 We recruited from 2 sources: 1) iConquerMS community members living in the United States who participated in an online survey of telemedicine17 and were interested in being interviewed (n = 264) and 2) patients from Veterans Health Administration’s MS Center for Excellence-East who had used telemedicine in the past 6 months (n = 66). Inclusion criteria consisted of MS diagnosis, age 18 years or older, and internet access. iConquerMS sent recruitment emails to eligible community members in 2 small batches until the quota targets were met. Twenty-seven individuals received the recruitment email, and of these, 13 were interviewed. Patients from the MS Center for Excellence-East were selected to reach the target number of males and people who are Hispanic and Black.

The HCPs were recruited from a spectrum of disciplines that assess and provide care for people with MS, including mental health providers, neurologists, nurse practitioners, and rehabilitation specialists. We used the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers’ (CMSC) clinical program list to identify a diverse group of providers with a range of years in practice, telemedicine experience, and practice settings (academic, private, government).

The PYs were recruited from private health insurance companies in the mid-Atlantic region, Medicare and Medicaid, VA telemedicine and information technology staff, and telemedicine trade associations.

Data Collection

To elicit accounts of participants’ experiences with telemedicine, we conducted 40- to 60-minute semistructured interviews via Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc). Except for 1 group interview with 4 people with MS from the VA, all other participants were interviewed individually. Both people with MS (interviewed by a qualitative researcher) and HCPs (interviewed by researcher clinicians with qualitative research experience) were asked an opening grand tour question19: “Please tell us about a memorable experience with telemedicine.” We then asked, “What made it memorable?” “What worked well?” and “What did not work well?” Interviewees were encouraged to reflect on MS specifically: “How do you see telemedicine being part of [your MS care/your MS practice] in the future?” Finally, interviewees were asked for their suggestions to improve the telemedicine experience. The PY questions focused on issues related to insurance coverage and competitive contracting for telemedicine for people with MS. The PYs were asked, “When it comes to coverage determination for telemedicine, what, if anything, has been unique for individuals with MS?”

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim except for 4 payer representatives who declined to be recorded but agreed to notetaking. Interviewees were offered a $50 honorarium.

Data Analysis

We took an inductive, thematic approach,20 using the qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA (VERBI Software) to aid in the initial sorting and sifting of interview transcripts. Information from the 4 unrecorded interviews was also included. We analyzed the data primarily within and secondarily across the 3 categories of participants. The study team met regularly to review emerging codes,21 identify common themes, reach consensus on interpretations of interviewees’ comments,22 and select salient quotations to illustrate themes.

Study Participants

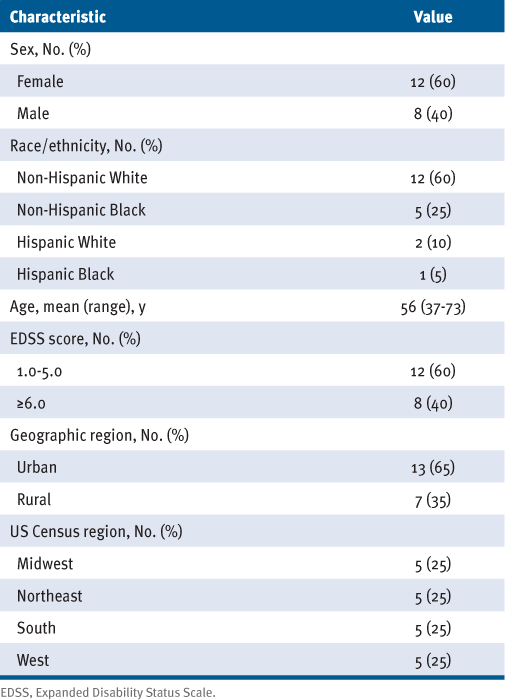

We recruited and obtained verbal informed consent from the final sample of 45 participants: 20 people with MS, 15 HCPs, and 10 PYs. The people with MS we interviewed were primarily non-Hispanic White (60%) and women (60%) from across the United States (TABLE 1). We interviewed 15 HCPs: 4 neurologists (27%), 4 nurse practitioners (27%), 1 neuro-ophthalmologist, 1 neuropsychologist, 1 physical therapist, 1 physiatrist, 1 psychiatrist, 1 psychologist, and 1 social worker. They worked in university medical centers (53%), private practices (27%), and VA medical centers (20%); had practiced for an average of 17 years; and had a reported average of 67% of their practice as telemedicine at the time of the interviews. The PYs included 2 public (Medicare/Medicaid) (20%) and 2 commercial (20%) insurance representatives and 6 policy experts (60%) who represented national behavioral health and telemedicine advocacy organizations and information and telemedicine technology administrators.

Characteristics of Study Participants With Multiple Sclerosis (n = 20)

RESULTS

Themes

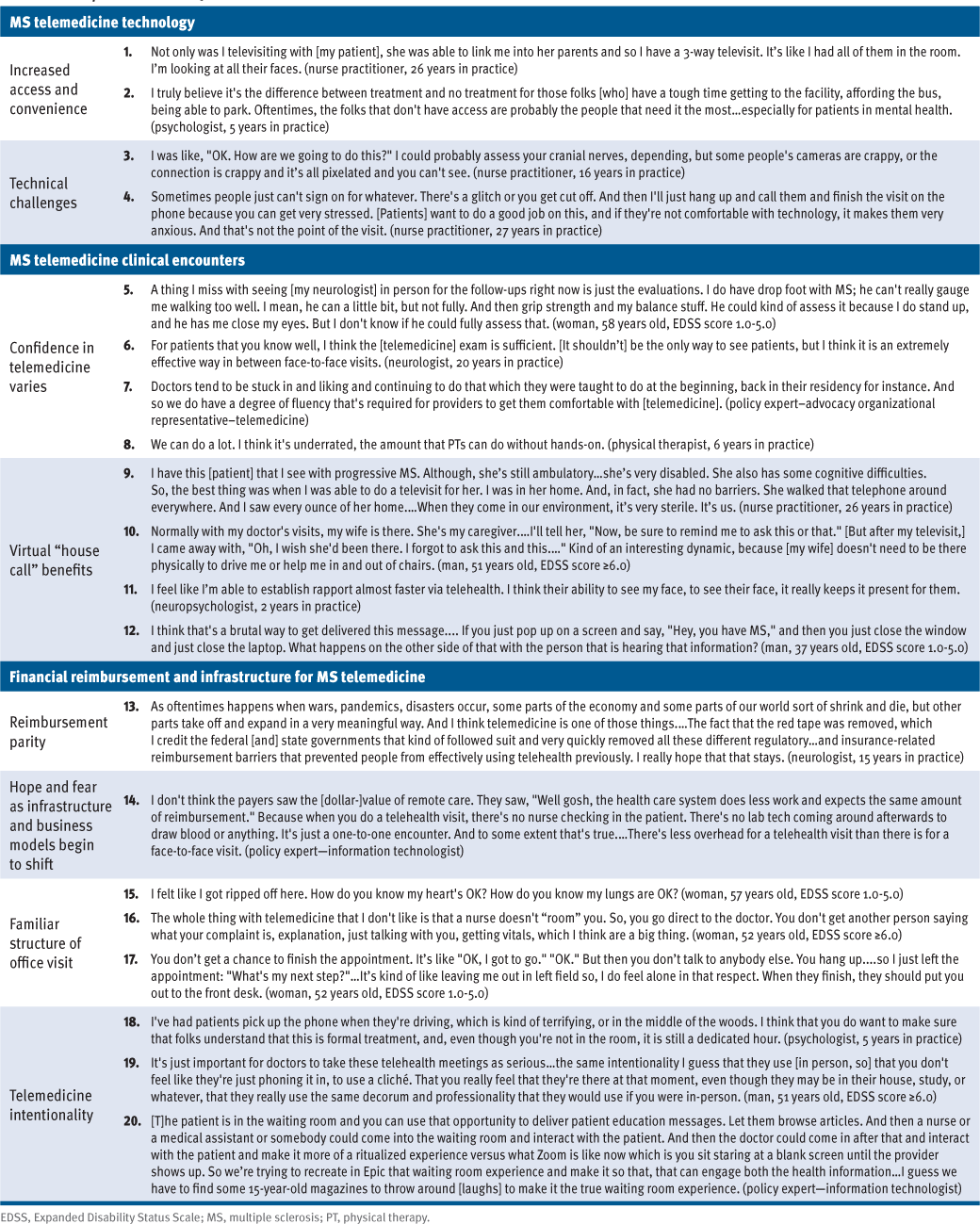

The findings are organized into 4 thematic areas related to MS telemedicine: technology, clinical encounters, financing and infrastructure, and shifting expectations (TABLE 2).

Representative Quotes of Themes

MS Telemedicine Technology

The COVID-19 pandemic sent everyone “scrambling,” the word used by HCPs and PYs to describe how it felt to shift care delivery. The significant benefits of telemedicine were noted by multiple interviewees and outweighed the challenges. The challenges were beginning to ease as familiarity with telemedicine technology and logistics were resolved. One PY (trade/advocacy) interviewee noted: “When [telemedicine] became a necessity…everybody was thrown in the deep end of the pool. And almost everybody said, ‘Hey, guys: we can swim!’ ”

Telemedicine increases access and convenience. For those who live far from an HCP, telemedicine is “literally a lifesaver,” a convenience that people with MS appreciated: “That’s 4 hours of my day that I don’t have to be in a car driving and paying tolls.” Meeting remotely made it possible for HCPs to contextualize people with MS in their family and home environment (quote 1) and expanded access to underserved patients (quote 2).

Technical challenges are most-cited downside to telemedicine. “None of us are IT specialists,” a psychologist said, describing being left to make appointments and troubleshoot technical and logistical challenges. Many shared a frustrating experience where they struggled to hear or see the other person or to find the correct telemedicine platform, especially early in the pandemic. Poor connectivity or camera quality interfered with a providers’ ability to do assessments (quote 3) and caused stress for both HCPs and patients (quote 4).

MS Telemedicine Clinical Encounters

Although some HCPs expressed confidence in their ability to practice via telemedicine, many said they were uncertain about how to transfer their skills to the new medium and were learning through “trial and error.” Some people with MS expected a telemedicine visit to be more like an in-person office visit, leaving them wanting more assurance and guidance. A PY emphasized the importance of deferring to HCPs for what is or is not clinically appropriate when using telemedicine and were careful to remind the public that telemedicine is “not a panacea.”

Confidence in telemedicine varies. The HCPs and people with MS expressed confidence in using telemedicine for routine follow-ups or MS symptom management. A nurse practitioner noted that her patients liked telemedicine, “especially if they’re kind of on cruise control with their MS.” However, another nurse practitioner observed that patients “need to be in front of their provider to feel like they get the same input they need.” When assessing neurologic changes, some HCPs and people with MS preferred an in-person examination (quote 5), although an established patient-provider relationship increased confidence in meeting virtually (quote 6).

Some people with MS were uncertain about what was clinically possible via telemedicine compared with an in-person office visit. They followed their provider’s lead and had a vested interest in accomplishing as much as possible within their allotted time. Based on what their providers did or did not do, some people with MS felt: “You can’t truly get an examination via telemedicine.”

The HCP with little or no experience with telemedicine had to adjust, often “improvising.” The adjustments they had to make required some confidence in their ability to experiment and get creative. One PY recognized the HCP’s lack of comfort and experience (quote 7). Some HCPs, especially those with more telemedicine experience, were very positive and confident providing care remotely (quote 8).

Virtual “house call” has clinical benefits. The HCPs noted the significant benefit of seeing their patients’ home environments. This allowed providers to make clinically important observations, such as how patients moved within their physical space (quote 9) or who was in the home providing support. One nurse practitioner discovered that her long-time patient was a smoker when she noticed an ashtray on his deck.

For some people with MS, having their caregiver present at an office visit is critical as they rely on them to ask questions and take notes. Telemedicine made it easier for caregivers to attend visits and provided HCPs with opportunities to meet family and caregivers who might not otherwise attend an in-person appointment. The opposite may also occur; a caregiver who typically drives the person with MS to an in-person appointment may be absent from a telemedicine visit (quote 10).

One HCP noted that telemedicine made it possible to see her patients’ facial expressions at the time when masks were required for all face-to-face visits (quote 11). Some people with MS appreciated the added level of attention they received from their HCP, noting that there were no interruptions by beepers and “no rushing from room to room to room.” Some people with MS felt that when a new diagnosis needed to be communicated, it was best done in person (quote 12).

MS Telemedicine Financing and Infrastructure

One PY described the COVID-19 pandemic as being responsible for “the single biggest transformation in health care delivery in 50 years; [and] it happened in 4 weeks.” This dramatic shift led to some growing pains and uncertainty for how sustainable the expansion of telemedicine would be in the near- and long-term future.

Reimbursement parity is critical to use and expansion of telemedicine. During the early pandemic, federal and state governments worked together to ensure access to telemedicine for all, including full reimbursement by payers for telemedicine visits and removal of “red tape,” such as relaxing licensing requirements and liability risks for telemedicine encounters across state lines (quote 13). Some individuals with MS appreciated waived co-pays for telemedicine appointments. Mental health providers found it easier to make the shift to telemedicine visits and could satisfy some of the unmet need created by the limited supply of mental health providers.

Stakeholders are hopeful and fearful as infrastructure and business models begin to shift. The consensus among those interviewed was that the change made during the pandemic should continue to enable telemedicine to become a permanent, viable alternative to in-person care. There was, however, uncertainty about the durability of structural changes that have made telemedicine possible (eg, provider licensing across state boundaries). Some HCPs and PYs were concerned that large provider groups and hospital systems might oppose continuing telemedicine because their budgets counted on revenue from facility and parking fees. Another concern was that insurers might use the lower overhead costs for telemedicine to justify reducing reimbursements (quote 14). Investors recognized the convenience and the value of telemedicine because they had used it, and therefore, as 1 PY said, he felt “optimistic” and “bullish.” Another PY noted that in terms of clinic efficiency, telemedicine decreased no-show rates. Finally, although we thought that PYs might be concerned about the potential for inappropriate or fraudulent billing for telemedicine, none had seen evidence that this had occurred to date.

MS Telemedicine Shifting Expectations

We found a lack of consensus on what constitutes a good telemedicine visit. Individuals with MS had specific expectations that a telemedicine visit should involve checking vital signs or conducting physical or neurologic examinations in addition to history-taking and conversation (quote 15).

The familiar structure of the office visit is currently absent from telemedicine. Individuals with MS needed more intentionality during telemedicine visits, mirroring aspects of in-person visits. In a typical in-person visit, other HCPs in the office participate, for example, in the process of being “roomed” and having vital signs taken (quote 16). The flow of an office visit, 1 individual with MS said, should be “like a good movie that has a good beginning, middle, and end—that starts off and you look back to what you did before.” Some suggested adding virtual rooms and ancillary staff to provide the structure of an in-person visit. One person with MS particularly missed the help scheduling follow-up visits (quote 17).

Telemedicine visits need more intentionality from both providers and patients. Several HCPs and individuals with MS described being frustrated with what felt like a lack of respect during the telemedicine visit. One HCP was alarmed when a patient called into their telemedicine visit while driving (quote 18). Similarly, individuals with MS noted times where the HCP lacked “intentionality” by failing to consult past medical records or to otherwise prepare (quote 19). The PYs recognized the need for addressing the patient experience, and at least 1 technology company mentioned plans to develop a virtual waiting room to replicate some of the look and feel of an outpatient office (quote 20).

DISCUSSION

Health care delivery has been reshaped by the use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some of what we documented revealed growing pains and steep learning curves. Unreliable internet and technical challenges with devices and software platforms will continue to plague telemedicine. With the passage of HR 3684, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act,23 funds were designated to improve internet access for underserved tribal lands,24 other underserved communities,25 and rural America.26 Some form of technical support will be part of any telemedicine program that serves patients with neurologic diseases.27

Technical issues with telemedicine are not unique to patients with MS and related neurologic disorders, but what is unique is the hands-on neurologic examination. Before the pandemic, individuals with MS expected and relied on live examinations to let them know if they had lost any ground since their last assessment. Without these points of comparison determined by a known, trusted clinician, some individuals with MS believed that remote examinations could not accurately determine their disease status. Similarly, some neurologists in the study said that they distrusted their ability to do a thorough and reliable assessment remotely, although others were confident in their abilities.

Some aspects of the remote neurologic examination are challenging, but not impossible, to perform according to the literature. In 2013, the equivalence between in-person and remote examinations was demonstrated with a patient aide.28 By 2019, work on the limitations of remote assessments had advanced to the point where Bove et al29 could report that “disability evaluation in mild to moderate MS is feasible using telemedicine without an aide at the patient’s location.” New technology is being developed to more accurately assess vision, cerebellar, and motor functions remotely.30 Questions surrounding provider confidence and competence and patient trust in remote neurologic examinations call for future research.

Education-, training-, and evidence-based guidelines need to establish effective clinical telemedicine programs for individuals with MS. The present findings suggest that lack of training in, exposure to, and experience with telemedicine limits what is possible via telemedicine. Even a self-described “old-school” neurologist who had been reluctant to try videoconferencing with his patients said he was pleased with the results and would consider adding components to his remote examination if he could learn more about the possibilities.

All clinicians who see patients with nervous system conditions could benefit from training in how to conduct a remote neurologic examination. Indeed, a substantial number of people with MS use their primary care physicians for their MS care. These patients are often older and have more severe impairments and are, therefore, likely to prefer telemedicine. The MS care providers could join with other provider groups to lower the cost of preparing and delivering training. With a platform such as Zoom, training and educational programs could use breakout rooms for clinicians who treat conditions affecting the nervous system, with demonstrations, practice sessions, downloadable materials, and Q&As on telemedicine, including how to conduct a remote neurologic examination. Understanding what specific quality measures can be gathered and what new tools have been developed to assess organ system function via televideo will build providers’ skills and confidence across disciplines.

Improved provider confidence will help individuals with MS trust their provider’s ability to measure changes in their clinical status. In addition, individuals with MS and their families need to know what to expect at a telemedicine appointment. They want to ensure that they can be seen and heard, to know how much time they have with the provider and when to bring out their list of questions. They would like the HCP to have reviewed the care plan. As with their providers, patients need educational telemedicine materials that include relevant research findings, use guidelines, technical training, and assistance avenues.

This report contributes to the growing body of literature on telemedicine use among indivduals with MS and neurologic disorders, before31–33 and after COVID-19,34–36 by including perspectives from them, HCPs, and PYs. This study confirms the literature that indicates that people with MS embrace telemedicine as a health care option, particularly during a pandemic.37,38 It also adds the views of providers, payers, and policy makers to research that outlined the impact of COVID-19 on MS during the early weeks of the pandemic, focusing on retooling disease-modifying therapies, monitoring technologies,35,36,39–43 and the consequences of delaying care and rehabilitation.44

Limitations to this study included the well-known challenges of recruiting payers and policy experts, resulting in a smaller PY sample than we would have liked; nevertheless, these interviewees offered an important perspective. Another weakness is that we interviewed only people with MS who had the technology to meet via some individuals-based platform. Some rural participants had a noticeable difference in internet quality and reliability.

Strengths of this study include a sample of individuals with MS that generally represents the demographic and disease characteristics of the MS population in the United States and a sample of HCPs that reflects the range of providers used by individuals with MS. Finally, these interviews took place 8 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, when telemedicine was the most prevalent if not the only way health care was being delivered and received. This created a unique opportunity to capture the early perceptions and insights of the participants while the adjustments they were having to make were still new, but with enough time so that all had experienced telemedicine.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the technical and human challenges to shifting to telemedicine as a sustainable and effective method for delivering affordable, high-quality, and universally accessible health care, individuals with MS, HCPs, and PYs recognized the benefits of telemedicine. There is a growing need for telemedicine training for providers, clear messaging to allow individuals with MS to understand what to expect during a telemedicine visit, and stakeholder assurances that telemedicine will be supported beyond the pandemic. Further work is needed to establish guidelines for virtual care for individuals with MS. Although there is variability in how comfortable some HCPs are with providing and people with MS are with receiving assessments via telemedicine, access to the highest-quality MS care by telemedicine is feasible and desirable, and the promise of widespread connectivity is encouraging. We encourage stakeholders to work together to build skills, confidence, and comfort, alongside equitable access to MS care delivery via telemedicine.

PRACTICE POINTS

» Telemedicine is an efficient, convenient platform for many aspects of multiple sclerosis (MS) care. Additional training for many MS health care providers is needed to expand telemedicine as a routine care delivery platform.

» Technological solutions can be found to fill in some of the gaps in the remote neurologic assessment for patients with MS.

» Given the proven value of telemedicine, stakeholders should work with federal and state governments to preserve and expand policy changes introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

We thank Hollie Schmidt of iConquerMS for recruitment assistance and Dr C. Daniel Mullins of The PATIENTS Program and chair of the Pharmaceutical Health Services Research Department at University of Maryland Baltimore, School of Pharmacy, for his counsel and support.

References

Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, . Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler 2020; 26: 1816–1821. doi: 10.1177/1352458520970841

Pétrin J, McColl MA, Donnelly C, French S, Finlayson M. Prioritizing the healthcare access concerns of Canadians with MS. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2021; 7(3): 20552173211029672. doi: 10.1177/20552173211029672

Bebo B, Cintina I, LaRocca N, . The economic burden of multiple sclerosis in the United States: estimate of direct and indirect costs. Neurology. 2022; 98(18): e1810–e1817. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200150

Langer-Gould A, Klocke S, Beaber B, . Improving quality, affordability, and equity of multiple sclerosis care. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 202; 8(4): 980–991. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51326

Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Hoaglin DC. Access to health care for people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13(4): 547–558. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071306

Zhou L, Parmanto B. Reaching people with disabilities in underserved areas through digital interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019; 21(10): e12981. doi: 10.2196/12981

Yeroushalmi S, Maloni H, Costello K, Wallin MT. Telemedicine and multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive literature review. J Telemed Telecare. 2020; 26(7–8): 400–413. doi: 10.1177/1357633X19840097

Butler CR, Wong SPY, Wightman AG, O’Hare AM. US clinicians’ experiences and perspectives on resource limitation and patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(11): e2027315. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27315

McGinley MP, Ontaneda D, Wang Z, . Teleneurology as a solution for outpatient care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. 2020; 26(12): 1537–1539. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2020.0137

Levin SN, Venkatesh S, Nelson KE, . Manifestations and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in neuroinflammatory diseases. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021; 8(4): 918–928. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51314

Meshkat S, Salimi A, Joshaghanian A, Sedighi S, Sedighi S, Aghamollaii V. Chronic neurological diseases and COVID-19: associations and considerations. Transl Neurosci. 2020; 11(1): 294–301. doi: 10.1515/tnsci-2020-0141

Brownlee W, Bourdette D, Broadley S, Killestein J, Ciccarelli O. Treating multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology. 2020; 94(22): 949–952. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009507

Roy B, Nowak RJ, Roda R, . Teleneurology during the COVID-19 pandemic: a step forward in modernizing medical care. J Neurol Sci. 2020; 414: 116930. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116930

Grossman SN, Han SC, Balcer LJ, . Rapid implementation of virtual neurology in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology. 2020; 94(24): 1077–1087. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009677

Telehealth was critical for providing services to Medicare beneficiaries during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic Office of the Inspector General, US Department of Health and Human Services. March 15, 2022. Accessed May 22, 2022.https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-02-20-00520.asp

MacFarlane A, Harrison R, Wallace P. The benefits of a qualitative approach to telemedicine research. J Telemed Telecare. 2002; 8(suppl 2): 56–57. doi: 10.1177/1357633X020080S226

Keszler P, Maloni H, Miles Z, . Telemedicine and multiple sclerosis: a survey of health care providers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J MS Care . Published online September 15, 2022. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2021-103

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983; 33(11): 1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444

Spradley JP. The Ethnographic Interview . Waveland Press; 2016.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3: 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers . SAGE Publishing; 2016.

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, . Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods 2017; 16: 1609406917733847. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733

H.R. 3684 - Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Congress.gov. November 15, 2021. Accessed May 22, 2022.https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3684/text

Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program. National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Accessed May 22, 2022.https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/resources/grant-programs/tribal-broadband-connectivity-program

Connecting Minority Communities Pilot Program. National Telecommunications and Information Administration. Accessed May 22, 2022.https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/resources/grant-programs/connecting-minority-communities-pilot-program

Read A, Gong L. States considering range of options to bring broadband to rural America. Pew Charitable Trusts. March 29, 2022. Accessed May 13, 2022.https://pew.org/3wE6bR8

Thomas EE, Haydon HM, Mehrotra A, . Building on the momentum: sustaining telehealth beyond COVID-19. J Telemed Telecare. 2022; 28(4): 301–308. doi: 10.1177/1357633X20960638

Wood J, Wallin M, Finkelstein J. Can a low-cost webcam be used for a remote neurological exam? Stud Health Technol Inform . 2013; 190: 30–32.

Bove R, Bevan C, Crabtree E, . Toward a low-cost, in-home, telemedicine-enabled assessment of disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019; 25(11): 1526–1534. doi: 10.1177/1352458518793527

Meinhold W, Yamakawa Y, Honda H, Mori T, Izumi SI, Ueda J. A smart tendon hammer system for remote neurological examination. Front Robot AI. 2021; 8: 618656. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2021.618656

Hatcher-Martin JM, Adams JL, Anderson ER, . Telemedicine in neurology: Telemedicine Work Group of the American Academy of Neurology update. Neurology. 2020; 94(1): 30–38. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008708

D’Haeseleer M, Eelen P, Sadeghi N, D’Hooghe MB, Van Schependom J, Nagels G. Feasibility of real time internet-based teleconsultation in patients with multiple sclerosis: interventional pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2020; 22(8): e18178. doi: 10.2196/18178

Robb JF, Hyland MH, Goodman AD. Comparison of telemedicine versus in-person visits for persons with multiple sclerosis: a randomized crossover study of feasibility, cost, and satisfaction. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019; 36: 101258. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.05.001

McGinley MP, Gales S, Rowles W, . Expanded access to multiple sclerosis teleneurology care following the COVID-19 pandemic. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2021; 7(1): 2055217321997467. doi: 10.1177/2055217321997467

Preziosa P, Rocca MA, Filippi M. COVID-19 will change MS care forever - No. Mult Scler. 2020; 26(10): 1149–1151. doi: 10.1177/1352458520929971

Meca-Lallana V. COVID-19 will change MS care forever - Yes. Mult Scler. 2020; 26(10): 1147–1148. doi: 10.1177/1352458520932767

Kristoffersen ES, Sandset EC, Winsvold BS, Faiz KW, Storstein AM. Experiences of telemedicine in neurological out-patient clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021; 8(2): 440–447. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51293

McKenna MC, Al-Hinai M, Bradley D, . Patients’ experiences of remote neurology consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Neurol. 2020; 83(6): 622–625. doi: 10.1159/000511900

Sastre-Garriga J, Tintoré M, Montalban X. Keeping standards of multiple sclerosis care through the COVID-19 pandemic. Mult Scler. 2020; 26(10): 1153–1156. doi: 10.1177/1352458520931785

Mateen FJ, Rezaei S, Alakel N, Gazdag B, Kumar AR, Vogel A. Impact of COVID-19 on U.S. and Canadian neurologists’ therapeutic approach to multiple sclerosis: a survey of knowledge, attitudes, and practices. J Neurol. 2020; 267(12): 3467–3475. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10045-9

Andrews JA, Craven MP, Jamnadas-Khoda J, . Health care professionals’ views on using remote measurement technology in managing central nervous system disorders: qualitative interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2020; 22(7): e17414. doi: 10.2196/17414

Block VJ, Bove R, Zhao C, . Association of continuous assessment of step count by remote monitoring with disability progression among adults with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019; 2(3): e190570. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0570

Brichetto G, Pedullà L, Podda J, Tacchino A. Beyond center-based testing: understanding and improving functioning with wearable technology in MS. Mult Scler. 2019; 25(10): 1402–1411. doi: 10.1177/1352458519857075

Alnajashi H, Jabbad R. Behavioral practices of patients with multiple sclerosis during Covid-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020; 15(10): e0241103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241103

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This work was supported by a grant awarded to Dr Wallin by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (HC-1610-25978) and the US Department of Veterans Affairs Multiple Sclerosis Centers of Excellence.