Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Impact of a Virtual Wellness Program on Quality of Life Measures for Patients Living With Multiple Sclerosis During the COVID-19 Pandemic

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) were vulnerable to the effects of physical inactivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. As patients returned to in-person visits, providers reported seeing increased weakness, balance issues, falls, worsening pain, and spasticity. Social isolation also contributed to increased stress, depression, and anxiety. This study explored whether attending virtual wellness programs was associated with improvements in standard quality of life questionnaire scores for patients with MS.

METHODS:

The purposive convenience sample consisted of 43 patients in the treatment group and 28 in the control group. Patients in the treatment group attended 2 monthly programs for 6 months and completed a demographic questionnaire, the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale, and the Medical Outcomes Study Pain Effects Scale (PES). Patients requested additional topics, resulting in 5 additional programs. The control group consisted of patients who chose not to attend the programs but agreed to complete the questionnaires.

RESULTS:

In comparing questionnaire responses (6 months minus baseline) among the participants in the treatment group, an association was found between higher meeting attendance and improvements in emotional well-being (P = .038), pain on the PES (P = .011), mindfulness on the SF-36 pain scale (P = .0472), and exercise on the PES (P = .0115).

CONCLUSIONS:

The results of this study suggest that a virtual wellness program may provide beneficial emotional support, physical exercise, and health promotion activities resulting in improved quality of life in people with MS. In addition, mindfulness and exercise programs may be beneficial in pain management.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a common, chronic, lifelong, unpredictable, and potentially highly debilitating neurologic condition that occurs more commonly in women than in men. It strikes most often in young adulthood but can even start in childhood and adolescence. There are nearly 1 million people living with MS in the United States.1

The COVID-19 pandemic affected every activity of the Penn MS and Related Disorders Center at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Clinic visits were initially halted and then switched to a virtual format. Many patients were isolated by stay-at-home orders. As some patients began to return to in-patient clinic visits, providers found that deconditioning related to limited activity had resulted in increased weakness, spasticity, and balance issues, as well as increased pain. Patients also reported increased stress, depression, and anxiety.

For many, the pandemic created a wide range of long-term challenges, which are correlated with worsening neurologic symptoms in patients with MS.2 Although patients were encouraged to self-isolate for protection from the virus, for some it posed a threat to their physical and mental well-being3 and resulted in reduced quality of life.4 In 1 online survey, researchers found that 50% of patients with MS either reduced or ceased their physical activity during the pandemic and 32% reported that their fitness level had decreased.4

To help patients with MS during the pandemic, Penn Center providers decided to offer virtual wellness programs. People with MS are becoming more interested in the concept of wellness,5,6 and there is evidence to suggest that in addition to disease-modifying therapies, lifestyle strategies that support wellness can help mitigate disease-related complications and comorbidities.7

Limited information on virtual wellness programs was found in the literature. Much of the current research has studied programs by businesses, academic institutions, and health care systems for employees and/or students. Initiated during the pandemic, studies dealing with patient populations, including patients who are disabled,8 are older,9–11 or have MS,12 showed that virtual programs were effective to some degree and were well received.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) has a Wellness Research Working Group to develop top research priorities.5 Through “social media listening,” 3 topics of interest to patients with MS were identified: diet, exercise, and emotional wellness; essentially, information they can use themselves to promote wellness.5 The researchers focused on these areas when planning the virtual programs.

METHODS

This exploratory study had a purposive convenience sampling design of patients with MS from the Penn MS and Related Disorders Center at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. No other criteria were required for study inclusion. The study was reviewed by the Office of the Institutional Review Board (IRB), University of Pennsylvania, and received exempt status. The IRB reviewers did not feel that a signed consent form was necessary; however, they suggested that study patients receive a 1-page consent statement that outlined the research purpose, their voluntary participation, study risks/benefits, and study expectations. This IRB-approved consent statement was sent to patients by secure email along with the study invitation.

The recruitment period was only 2 months due to constraints, including pandemic-related stay-at-home restrictions and lack of vaccine availability. In addition, the researchers hoped to intervene with the virtual wellness program when it was most needed and to concurrently collect data and evaluate the program’s potential positive effect on participants. During the 2-month recruitment period, the providers in the MS clinic, including physicians, nurse practitioners, and nurses, were asked to mention the wellness programs and study to the patients seen during that time, either in the clinic or virtually. All patients who expressed an interest or who might benefit from the programs were sent a secure email invitation and the consent statement from the nurse or social worker; 239 emails were sent. Patients were offered the option of being a part of the treatment group or the control group.

The final sample consisted of 43 patients in the treatment group and 28 patients in the control group. Patients in the treatment group were asked to attend 2 monthly wellness programs for 6 months and to complete a demographic questionnaire, the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS-5), and the Medical Outcomes Study Pain Effects Scale (PES) at baseline, month 3, and month 6. Patients in the control group chose not to attend the programs but agreed to complete the same questionnaires at the same intervals.

Baseline demographic and patient characteristics are summarized in TABLE S1, available online at IJMSC.org. Of the 43 patients in the treatment group, 39 (90.7%) were female and 4 (9.3%) were male; the mean ± SD age was 56.79 ± 10.80 years. Thirty-eight patients (88.4%) were White, 4 (9.3%) were Black, and 1 (2.3%) was Hispanic. Forty-one participants (95.3%) had an education beyond high school, and 18 (41.9%) had a graduate degree (beyond the bachelor level). The mean ± SD number of years since diagnosis was 15.60 ± 10.45, and 22 patients (51.2%) felt isolated. Of the 28 patients in the control group, 20 (71.4%) were female and 8 (28.6%) were male; the mean ± SD age was 49.46 ± 10.29 years. Twenty-two control participants (78.6%) were White, 2 (7.1%) were Hispanic, 2 (7.1%) were Asian American, 1 (3.6%) was Black, and 1 (3.6%) was Native American. Twenty-seven control patients (96.4%) had an education beyond high school, and 17 (60.7%) had a graduate-level degree. The mean ± SD number of years since diagnosis was 12.86 ± 7.11, and 15 control patients (53.6%) felt isolated.

The wellness programs were presented virtually via video conferencing (Zoom or BlueJeans) with links provided in an individual email. When the participants logged on, they could choose to mute their video and/or audio if they wanted to protect their anonymity, but many interacted with the speaker or one another. Patients provided ample messages with positive feedback and requests for different topics. As a result, there were 5 additional programs added to the schedule; in total, there were 17 programs over 6 months. An exercise program was offered 6 times and a mindfulness program was offered 3 times.

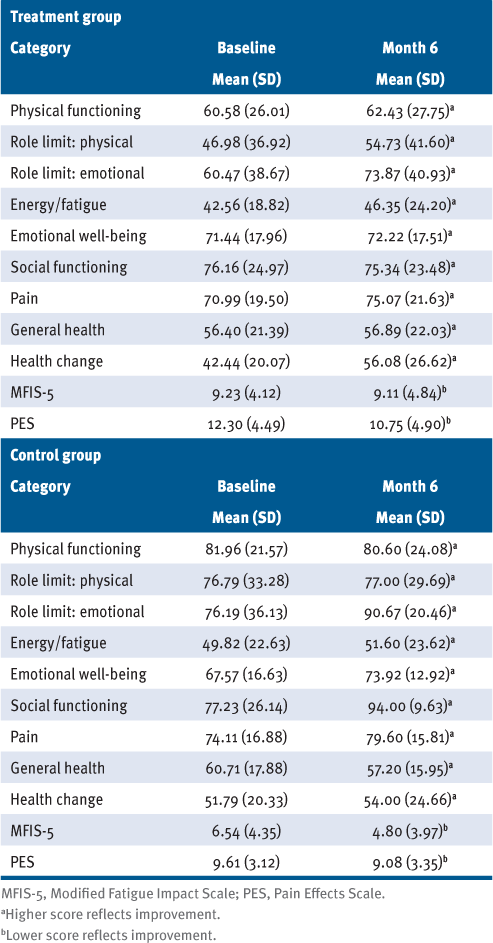

After finding significant baseline differences between the treatment and control groups due to lack of randomization, an insufficient sample size to adequately adjust for confounding in the treatment group assignments, and the exploratory nature of this study, the analysis focused on potential differences within the treatment group: evaluation of whether frequency of virtual wellness program session attendance (eg, total number, number of session subtype) was associated with differences in questionnaire response changes. Given the exploratory nature of the study with limited data points, it was decided to limit the scope of the analysis to the 6-month end point. Baseline and 6-month measurements for both groups are presented in TABLE 1. Differences across the strata were tested using a Jonckheere-Terpstra test for trend or a 2-sample t test, depending on the number of strata being compared.

Average Baseline and 6-Month Measurements

RESULTS

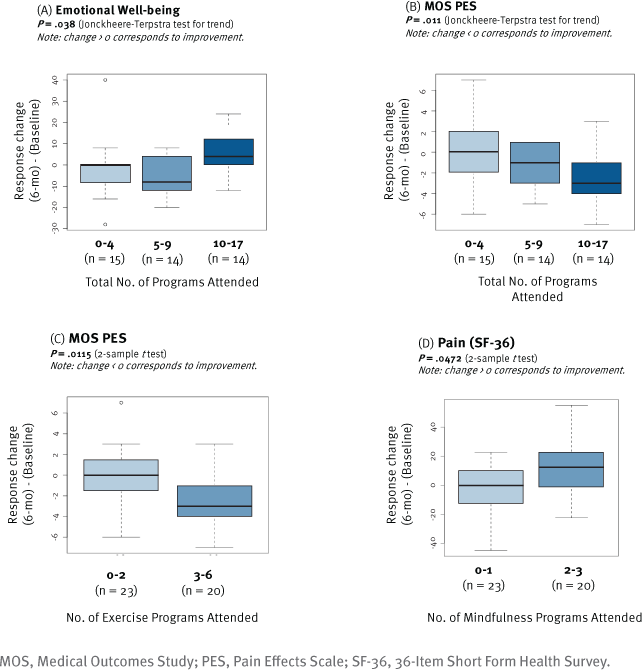

Changes in questionnaire responses were first analyzed stratified on the total number of meetings attended. Of the 43 participants in the treatment group, 15 (34.88%) attended 0 to 4 total meetings, 14 (32.56%) attended 5 to 9 meetings, and 14 (32.56%) attended 10 to 17 meetings. A Jonckheere-Terpstra test suggested that higher meeting attendance was associated with improvement in emotional well-being (P = .038) (FIGURE 1A) and pain on the PES (P = .011) (FIGURE 1B).

Changes in Questionnaire Responses Between Baseline and 6 Months According to the Number and Type of Programs Attended

According to research performed by the NMSS, exercise is a topic of interest for patients with MS.5 Exercise is important for overall health and well-being and is also beneficial in managing MS symptoms, including cardiovascular, strength, bowel/bladder function, fatigue, mood, cognitive function, bone density, and flexibility.6 Exercise can also be beneficial in reducing pain.13,14 Pain is a common symptom for patients with MS15 and is associated with fatigue, depression, anxiety, and reduced mental health quality of life.13

A virtual exercise program was offered each month for a total of 6 sessions. Thirty-five patients (81.4%) in the treatment group attended at least 1 session. The programs were presented by a certified personal trainer who also has MS. Her programs were based on NMSS evidence-based exercise and lifestyle physical activity recommendations for patients with MS throughout the disease course.16 She structured the programs so that patients could perform the exercises from a sitting or standing position.

After stratifying patients into 2 groups (23 [53.5%] who attended 0–2 exercise sessions and 20 [46.5%] who attended 3–6 exercise sessions), it was determined that those who attended 3–6 exercise programs had significant improvement compared with baseline on the PES (P = .0115) (FIGURE 1C). Exercise program attendance was not associated with improvement on any other outcome measures.

There is also evidence that the practice of mindfulness can be helpful in pain relief, but little work has been done in relation to patients with MS.15 One study conducted a cross-sectional survey to evaluate the association between pain and mindfulness in patients with MS. The results suggested that there is a clinically meaningful and highly significant relationship between mindfulness and pain interference in MS.15 A mindfulness program was offered a total of 3 times during this study.

Differences in questionnaire response changes were also analyzed depending on the number of virtual wellness program subtypes attended. Thirty patients (69.8%) in the treatment group attended at least 1 of the 3 mindfulness sessions. After stratifying patients into 2 groups (23 [53.5%] who attended 0–1 mindfulness sessions and 20 [46.5%] who attended 2–3 mindfulness sessions), it was found that patients who attended more mindfulness programs had a significant level of improvement compared with baseline on the SF-36 pain scale (P = .0472) (FIGURE 1D). The researchers did not find significant associations between mindfulness program attendance and any other questionnaire responses.

Diet is another key topic requested by patients with MS to promote wellness.6 Although there is no “best diet,” maintaining a healthy diet promotes the overall health and well-being of patients with MS.17 A registered dietitian who also has MS presented a healthy approach to nutrition for people living with MS and addressed questions about specific diets.

Movement is paramount to maintaining mobility, so in addition to the exercise programs, 3 other movement classes were offered. In 1 session, an occupational therapist provided suggestions to address common functional problems that patients with MS face.18 There was also a yoga program led by a trained yoga instructor who has MS. There is evidence that yoga benefits people with MS by reducing depression, decreasing pain and fatigue, increasing lung capacity, improving strength and flexibility, decreasing stress, and promoting muscle relaxation, lower blood pressure, and an improved quality of life.19 Finally, a dancer with MS gave a session. She performed a ballet she choreographed chronicling her recovery from an MS exacerbation using the walker she required at that time and the neurologic examination comparing her weak side with the unaffected side. The results of 1 meta-analysis suggest that dance movement therapy decreases depression and anxiety and increases quality of life and interpersonal and cognitive skills.20 In recent years, research suggesting positive effects from dance therapy on patients with MS has increased.21–24

Sleep difficulties are common among people living with MS, and 1 study found that patients with MS had worse sleep quality during the pandemic than the general population.25 A University of Pennsylvania sleep medicine physician presented “Lessons from a Sleep Physician: Falling Asleep and Staying Asleep, Critical Lessons for Battling MS Fatigue.” Contributing factors to sleep disturbance include vitamin D deficiency; adverse effects from medications, including disease-modifying therapies, steroids, and fatigue medications; fatigue-related daytime napping; decreased exercise related to fatigue or MS-related disability; emotional changes such as stress, anxiety, or depression; and other MS symptoms, such as restless legs, pain, urinary and bowel symptoms, and temperature dysregulation.26 The speaker provided an interactive program on the causes of sleep deprivation and ways to foster quality sleep.

Emotional wellness is also a topic of interest to patients with MS.5 Patients who attended more meetings in this study had a significant level of improvement compared with baseline in emotional well-being (P = .038) (Figure 1A). A program was presented by a comedian with MS about living with MS. Laughter can be beneficial as it has been found to relieve stress and tension, improve the immune system, increase personal satisfaction, and improve mood.27 In planning the program, the researchers worried whether a comedy program would be well received and/or beneficial to the patients. The comedian was also concerned about conducting a virtual comedy program where the microphone of many participants would be muted; however, the program was very successful and patients offered positive responses in the chat box: “OMG! I needed this so much!!” “Best hour I’ve spent in way too long!! Thank you!!” (TABLE S2).

The nurse practitioners from the MS center provided a program on MS symptoms. Because of their training and expertise, they understand the complexity of MS treatments, including treatments for symptom management.28 The program was presented in an open forum that allowed for patient questions and comments on ways to deal with MS symptoms.

Finally, there was a program provided by a primary care provider, an important role in the multidisciplinary team since they will likely see the patient more frequently than the neurologist in a years’ time.29 The primary care provider stressed that the patient with MS must also take care of non-MS issues to maintain overall wellness.

DISCUSSION

The results of this exploratory study suggest that virtual wellness programs may be a beneficial tool for patients with MS, whether isolation is caused by a pandemic or by disability. The programs provide information and activities to address the physical effect of deconditioning, as well as group interaction and support to address social isolation.

Ten of the 17 programs were presented by individuals who have MS, which may have contributed to the very active group interaction, as well as the positive responses: “I wanted to thank you for the wonderful programs. They have really helped me and have been uplifting. What I really like about the programs is that the presenters also have MS. I was diagnosed in 2011 and have pretty much kept it a secret. The programs are helping to decrease some of my anxiety and worries about somebody at work finding out that I have MS. Hearing the presenters share their stories is encouraging me to also want to open up and share with other people in my life. The programs have been inspirational and I am so happy I was able to join.”

The pandemic provided a perfect opportunity to explore the concept of virtual wellness programs. One researcher found that online opportunities for physical activity for patients with MS were a valued option and recommended that such programs be continued after the pandemic.30 Many of the participants in this study continue to attend the 2 monthly virtual wellness programs that have continued for the patients with MS beyond this study.

The positive feedback the researchers received in this study, both verbally and in writing, confirmed that the wellness programs were valuable to the participants. A patient wrote, “I’ve lived with MS for over 20 years, and the Penn MS Wellness Group has absolutely been the most positive, helpful, caring experience for me in terms of my health care team going out of their way to provide meaningful, relevant, helpful, and regular programming while also creating a supportive, safe, warm community made up of patients, caregivers, and medical providers. The group … provides insight that has helped me live better with MS. Thank you so much for this wonderful group!”

This study has several limitations. The study design changed because (1) the researchers could not compare the 2 groups due to lack of randomization, (2) additional programs were added by patient request, and (3) the scope of the analysis was limited to the 6-month end point. Many of the members of the sample were older white females who were highly educated, with most having degrees beyond high school. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to a more diverse population. Vaccine availability during the study may have contributed to the improvement of patient well-being.

The results of this study suggest that a virtual wellness program can be beneficial to patients living with MS. Interventions on diet, exercise, and emotional wellness may be associated with improved MS symptoms, as well as improvement in overall health and quality of life. The study also suggests that mindfulness and exercise programs may be beneficial in pain management. A randomized trial is warranted to further study effectiveness.

PRACTICE POINTS

» For many patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), quarantining during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in social isolation as well as physical deconditioning.

» People with MS have expressed an interest in prioritizing wellness, particularly through diet, exercise, and emotional wellness.

» Virtual wellness programs promote social interaction as well as physical and mental support through a variety of wellness activities, and they may be valuable not only during a pandemic but at any time for any individual with MS who is isolated due to disability.

References

How many people live with MS? National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Accessed March 24, 2022.https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/How-Many-People

Bonavita S, Sparaco M, Russo A, Borriello G, Lavorgna L. Perceived stress and social support in a large population of people with multiple sclerosis recruited online through the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Neurol. 2021; 28: 3396–3402. doi: 10.1111/ene.14697

Synnott E. Bridging the gap in multiple sclerosis rehabilitation during Covid-19. J Mult Scler. 2020; 7(1): 01.

Kalron A, Dolev M, Greenberg-Abrahami M, . Physical activity behavior in people with multiple sclerosis during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: results of an online survey. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021; 47: 102603. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102603

Motl RW, Mowry EM, Ehde DM, . Wellness and multiple sclerosis: the National MS Society establishes a Wellness Research Working Group and research priorities. Mult Scler. 2018; 24(3): 262–267. doi: 10.1177/1352458516687404

Exercise. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Accessed March 24, 2022.https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Living-Well-With-MS/Diet-Exercise-Healthy-Behaviors/Exercise

Moss BP, Rensel MR, Hersh CM. Wellness and the role of comorbidities in multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2017; 14(4): 999–1017. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0563-6

Roca C. Effectiveness of virtual wellness programming for adults with disabilities: clients’ perspectives. J Allied Health. 2021; 50(2): e63–e66.

Gao Z, Lee JE, McDonough DJ, Albers C. Virtual reality exercise as a coping strategy for health and wellness promotion in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Med. 2020; 9(6): 1986. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061986

Sanchez-Villagomez P, Zurlini C, Wimmer M, . Shift to virtual self-management programs during COVID-19: ensuring access and efficacy for older adults. Front Public Health. 2021; 9: 663875. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.663875

De Biase S, Cook L, Skelton DA, Witham M, Ten Hove R. The COVID-19 rehabilitation pandemic. Age Ageing. 2020; 49(5): 696–700. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa118

Dunne J, Chih HJ, Begley A, . A randomised controlled trial to test the feasibility of online mindfulness programs for people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021; 48: 102728. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102728

Marck CH, De Livera AM, Weiland TJ, . Pain in people with multiple sclerosis: associations with modifiable lifestyle factors, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and mental health quality of life. Front Neurol. 2017; 8: 461. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00461

Demaneuf T, Aitken Z, Karahalios A, . Effectiveness of exercise interventions for pain reduction in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019; 100(1): 128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.08.178

Senders A, Borgatti A, Hanes D, Shinto L. Association between pain and mindfulness in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018; 20(1): 28–34. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2016-076

Kalb R, Brown TR, Coote S, . Exercise and lifestyle physical activity recommendations for people with multiple sclerosis throughout the disease course. Mult Scler. 2020; 26(12): 1459–1469. doi: 10.1177/1352458520915629

Diet and nutrition. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Accessed March 24, 2022.https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Living-Well-With-MS/Diet-Exercise-Healthy-Behaviors/Diet-Nutrition

Ghahari S, Finlayson M. A resource for healthcare professionals: occupational therapy in multiple sclerosis rehabilitation. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. 2018. Accessed March 24, 2022.https://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/Clinical_Bulletin_Occupational-Therapy-in-MS-Rehabilitation.pdf

Rogers KA, MacDonald M. Therapeutic yoga: symptom management for multiple sclerosis. J Altern Complement Med. 2015; 21(11): 655–659. doi: 10.1089/acm.2015.0015

Koch SC, Riege RFF, Tisborn K, Biondo J, Martin L, Beelmann A. Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes: a meta-analysis update. Front Psychol. 2019; 10: 1806. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01806

Sonke J, Langley J, Whiteside B, . Movement for multiple sclerosis: a multisite partnership for practice and research. Arts Health. 2021; 13(2): 204–212. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2020.1852435

Ng A, Bunyan S, Suh J, . Ballroom dance for persons with multiple sclerosis: a pilot feasibility study. Disabil Rehabil. 2020; 42(8): 1115–1121. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1516817

Mandelbaum R, Triche EW, Fasoli SE, Lo AC. A pilot study: examining the effects and tolerability of structured dance intervention for individuals with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2016; 38(3): 218–222. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1035457

Scheidler AM, Kinnett-Hopkins D, Learmonth YC, Motl R, López-Ortiz C. Targeted ballet program mitigates ataxia and improves balance in females with mild-to-moderate multiple sclerosis. PloS One. 2018; 13(10): e0205382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205382

Motolese F, Rossi M, Albergo G, . The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people with multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2020; 11: 580507. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.580507

Sleep. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Accessed March 24, 2022.https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Living-Well-With-MS/Diet-Exercise-Healthy-Behaviors/Sleep

Healthy lifestyle: stress management. Mayo Clinic. Accessed March 24, 2022.https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress-relief/art-20044456

Harris C, George S, Kahovec C, Prociuk M, Roll A, McEwan L. The role of the multiple sclerosis nurse practitioner. NP Current. 2021; 7: 20–24.https://npcurrent.ca/pdfs/Harris_C_et_al-Role_of_the_MS_NP.pdf

What’s my role in multiple sclerosis care: a guide for primary care physicians. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed March 24, 2022.https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/qa-whats-my-role-in-multiple-sclerosis-care

Koopmans A, Pelletier C. Physical activity experiences of people with multiple sclerosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabilities. 2022; 2(1): 41–55. doi: 10.3390/disabilities2010004

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Ms Weinstein provided statistical support and is funded by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program. External speakers were paid honoraria supported by a grant from the Board of Women Visitors of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and funding earned through successful completion of annual projects with the Neuroscience Service Line of Penn Medicine.

PRIOR PRESENTATION: Aspects of this study were presented in poster form at the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers Annual Meeting; October 25-28, 2021; Orlando, Florida.