Publication

Research Article

Modeling the Multiple Sclerosis Specialist Nurse Workforce by Determination of Optimum Caseloads in the United Kingdom

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

It is estimated that there are more than 100,000 people in the United Kingdom who have multiple sclerosis (MS). Patient experience and outcome are improved by access to a specialist nursing service. The aim of this study was to perform demand modeling to understand the need for MS nursing interventions, and thus inform modeling of the future UK MS nursing workforce.

Methods:

Existing national data and specific workload and service data were collected from 163 MS specialist nurses who completed a questionnaire on activity and complexity of work both done and left undone.

Results:

Data were received from across all of the United Kingdom. Twenty-nine percent of respondents were specialist nurses in the field for 3 years or less. Unpaid overtime was regularly performed by 83.4% of respondents. The MS specialist nurse was part of all areas of the patient journey. Areas of work left undone were psychological interventions, physical assessments, social interventions/benefits, and recommending or prescribing medications.

Conclusions:

The current recommended caseload of 358 people with MS per full-time equivalent seems to be too high, with a considerable amount of work left undone, particularly psychosocial care. Factors such as travel time, complexity of caseload, changing drug therapies, and societal issues such as the benefits system contributed to driving demand/workload.

A significant challenge for the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and for health care worldwide is to determine how much time nurses require to care for different patient groups and the relevant level of expertise necessary to do so in a variety of settings. This is challenging as, in common with many human activities, nursing is both complex1,2 and dynamic in nature. In view of this, it is difficult to achieve consensus over which factors are even relevant to a proposed model.3 Nursing is complex work, yet most approaches to examining the work performed by nurses view their actions as a simple linear series of tasks.4

It is estimated that there are more than 100,000 people in the United Kingdom who have multiple sclerosis (MS).5 This estimate is based on work by Mackenzie et al.6 The same study suggested that the number of people in the United Kingdom with MS was growing at 2.4% per year due to people with MS living longer. According to a recent report by NHS Digital, in England, 120,786 hospital-admitted patient care episodes occurred from April 1, 2016, to March 31, 2017, for patients with a diagnosis of MS, with nearly half of these episodes (54,732 [45%]) having MS as the primary diagnosis.7

In 2014 the MS Trust published caseload guidance based on consensus for MS specialist nurses (MSSNs) in the United Kingdom.8 This guidance recommended 358 people with MS as a caseload per full-time equivalent (FTE) MSSN. As services and demands have changed, this number requires review. One of the drivers for this is the increasing number of treatment options that require extra resources, such as supporting patients with shared decision making, patient education, and monitoring.

In the United Kingdom the work of specialist nurses is varied, with factors such as job title and level of practice not necessarily being suitable markers of the complexity of a specialist nurse’s practice.9 As a result, nurse specialists in the United Kingdom often practice at a variety of levels of complexity, may offer a range of interventions, and work within a number of widely differing service provision models. All these variations can influence the burden of individual workloads. A number of other factors have been demonstrated to have an effect, including the complexity of patient needs10 and the ability to access other members of the multidisciplinary team.11

The aim of this study was to perform demand modeling to understand the need for MS nursing interventions and, by doing so, inform modeling of the future UK MS nursing workforce. This included gaining an understanding of how the current workforce meets demand, the types of work left undone, the amount of overtime (either paid or unpaid) necessary to meet demand, and the available skill mix in terms of complexity.

Methods

A Priori Data Set Complexity and Factors Affecting Workload

To examine patterns and workload of other specialist nurses working in long-term conditions, a curated data set of approximately 77 million hours of advanced practice specialist work (n = 18,000 nurses) since 2009 was consulted. These data reflect varying levels of complexity of work and have generated indicators of workload to use stochastic approaches to optimum caseload calculation. A number of common factors emerged from this data set that typically affect specialist nurse workload, for example, the ability to interact with other members of the multidisciplinary team,11 caseload complexity,12,13 availability of administrative assistance,14 access to other services,15 and education and experience.16 Other factors including access to nonmedical prescribing17 and the ability to independently request investigations were also significant. Where nurse specialists are able to prescribe and independently request investigations, they are enabled and empowered to make independent decisions rather than “door hang” for the decisions of others (eg, wait for a clinician to approve prescribing medication or ordering investigations).

Consensus Workshop of Expert Opinion: Checking Assumptions

To use the existing a priori data set and the online data collection tool it was necessary to determine if the assumptions made regarding workload and activity of the group applied to MSSN’s work. A consensus workshop of 13 MSSNs from across the United Kingdom was arranged to check and challenge assumptions drawn from the data set. In this workshop the participating nurses were asked to explain their work in detail, examining areas such as the work environment, physical and psychological domains, social issues, case management, administration, and work left undone. It was apparent that the MSSNs experienced a comparable work pattern to that found in similar long-term conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease13 and rheumatology,16 apart from two issues that were raised by the attendees: 1) the amount of time spent traveling, especially in rural practices; and 2) the impact of patient benefits claims on workload. To investigate these issues, two additional questions were added to the previously used questions.

Data Collection Specific to MS

To explore the MSSN’s demographic data, caseload, and workload, a survey consisting of 24 questions was developed for the MSSN population by consensus using clinical, patient, and academic experts based on a previously used national study.13 The questionnaire was designed to collect data on the activity and complexity of specialist nursing services provided, including work left undone; it used a format similar to the national optimum caseload modeling project developed by the National Cancer Action Team’s Alexa caseload tool first used in lung cancer and subsequently in other long-term conditions.15 There was also a free-text option for further comments from respondents. The questionnaire was transferred to an online survey tool (administered using a SurveyMonkey secure account). The survey link was distributed through the MS Trust and other professional mailing lists, such as the UK Multiple Sclerosis Specialist Nurse Association, during July 2018. One hundred sixty-three participants responded to the questionnaire. Only a single response could be submitted from each computer. Analysis of the survey data took place in September 2018.

Data Analysis

Data were exported into a spreadsheet (Excel; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) and modeled using descriptive statistics, for example, demographics, pay band and length of service, workload, interventions delivered, work left undone, and educational background. Free-text comments were analyzed using qualitative data analysis software (NVivo 11; QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) and thematic content analysis.18 Thematic content analysis is the approach best suited to free-text questions in an otherwise quantitative questionnaire, because it does not rely on interpretation of data but instead reflects a “low hovering over the data.” Demand modeling (causal) was performed using technical computing software (Mathematica 10; Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL).

Caseload Calculations

Responses to the SurveyMonkey workload questionnaire were received from 163 MSSNs who completed it in whole or in part. The total population of MSSNs in the United Kingdom is estimated to be 290 by headcount (source: MS Trust), so this equates to an approximately 56% response rate.

The data sets were then used to construct a demand model focused on workload, which included work that was necessary but not done. This approach uses a combination of qualitative and causal modeling that looks at the real-world experience of workers and past trends. Once the demand, including the deficit, had been determined, the supply (caseload calculation range) was determined.

Results

Demographic Data and UK MS Epidemiology

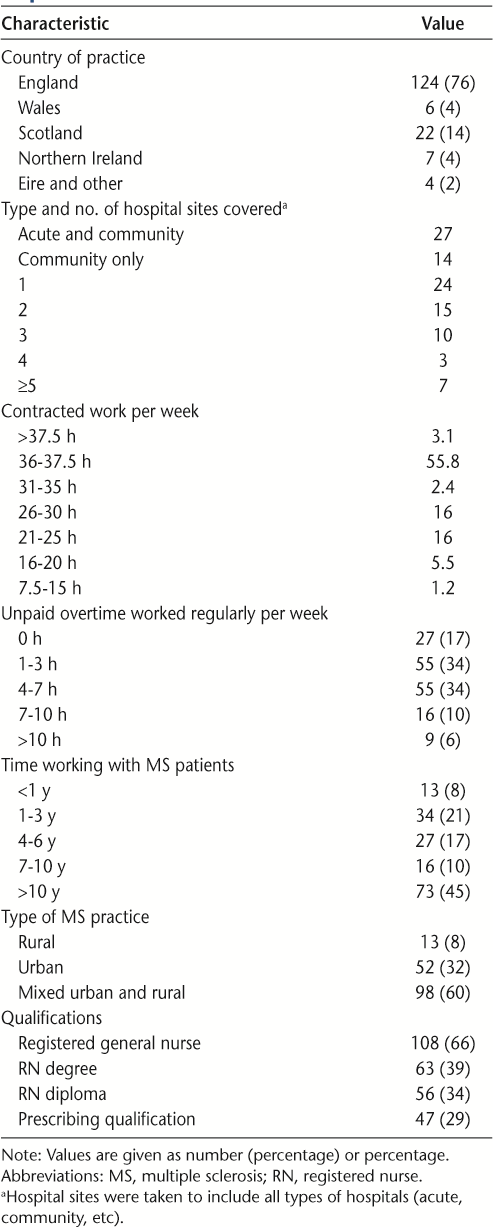

The country of practice, number of hospital sites covered, number of hours worked per week, number of unpaid overtime hours worked per week (including working through meal breaks), type of practice, length of time working with patients with MS, and educational qualifications are summarized in Table 1. The 163 respondents to this questionnaire represent approximately 139.8 FTE based on the median number of contracted hours per week reported. The amount of unpaid overtime worked by respondents as a whole equates to approximately 664 hours per week (assuming median values of 2, 5.5, 8.5, and 10 hours extra for the four categories reporting unpaid overtime), or 4.07 hours each, which is equivalent to approximately 17.2 FTE unpaid overtime being worked per week in total.

Background characteristics of the 163 respondents

Time Spent Traveling Between Sites or Making Community Visits

The amount of time respondents spent per week traveling between different hospital sites or making community visits was examined. Respondents were asked not to include time spent commuting to and from their place of work in this estimate. Only 36 respondents (22.1%) did not spend time traveling, 44 (27.0%) spent less than 2 hours per week, 48 (29.4%) between 2 and 4 hours, 22 (13.5%) between 4 and 6 hours, and 13 (8.0%) more than 6 hours. Using the median travel time for each group, this equates to 363 hours of travel time per week for the whole group. Travel time was then compared by type of practice (rural, urban, or mixed) (Figure S1, published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org). There seems to be an association with having a rural practice or a mixed rural and urban practice and time spent traveling.

Administrative Support Provided to Respondents

In answer to how much administrative support (help with typing letters or doing routine nonclinical administration) they received each week, 14% responded that they received no administrative support at all. A further 26% responded that they received administrative support only for clinic letters. Among respondents who received administrative support to use as they wished, 10% received 1 to 5 hours of support, 12% received 6 to 12 hours, 13% received 13 to 20 hours, and 25% received more than 20 hours per week.

Unfilled and Frozen Vacancies

To ascertain the level of unfilled and frozen posts (frozen posts are those that are currently vacant but not being actively recruited to, usually for financial reasons), respondents were asked how many, if any, posts were unfilled in their specialty. Seventy-six percent of respondents had no unfilled posts, 10% had fewer than one FTE unfilled, another 10% had one FTE unfilled, 5% had two FTEs unfilled, and 1% had five or more posts unfilled. One respondent reported frozen posts. This equates to approximately 35 FTE posts unfilled in total from this population.

Respondent Work Patterns

Estimated Caseloads

Respondents were asked to estimate their individual caseloads: 34% had caseloads of more than 500 patients, and only 26.9% had caseloads of 300 patients or less (Figure S2). Taken as a whole, this represents an approximate total caseload of 73,750 patients for all 156 respondents.

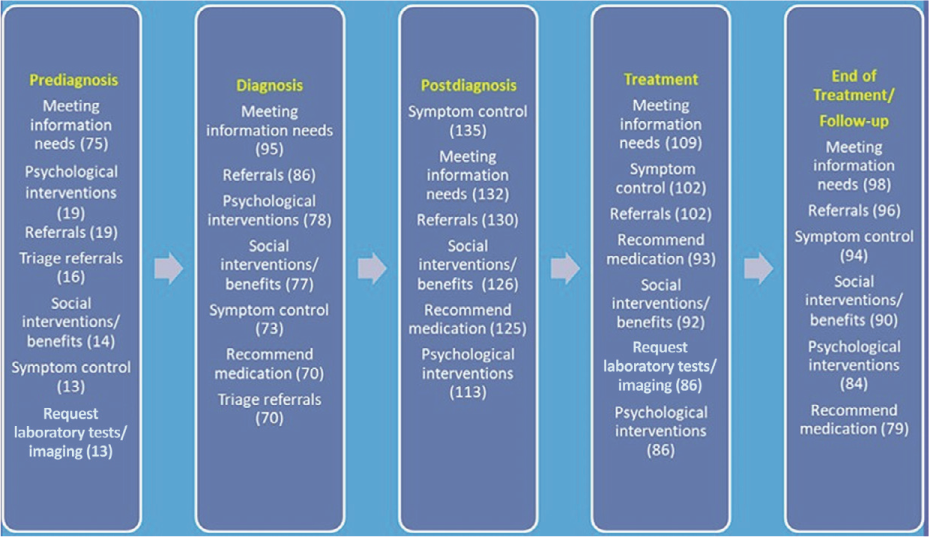

Work Done

Respondents were asked whether they performed certain tasks at each level of the treatment pathway (prediagnosis, diagnosis, postdiagnosis, treatment, and end of treatment/follow-up). As a group, MSSNs are involved in all stages of the treatment pathway. The responses are summarized in Figure S3.

The six or seven most common interventions at each treatment stage are shown in Figure 1. The most common tasks throughout the treatment pathway were meeting information needs, symptom control, referrals, psychological interventions, and social interventions/benefits advice.

Most common interventions at each treatment pathway stage

Sessional Work

A total of 1547 sessions per week were recorded by all the respondents. Provision of an advice line accounted for 565 sessions (36.5%); nurse-led outpatient clinics, 389 sessions (25.2%); telephone clinics, 277 sessions (17.9%); inpatient working, 121 sessions (7.8%); joint clinics, 84 sessions (5.4%); consultant-lead outpatient clinics, 63 sessions (4.1%); and virtual clinics, 48 sessions (3.1%).

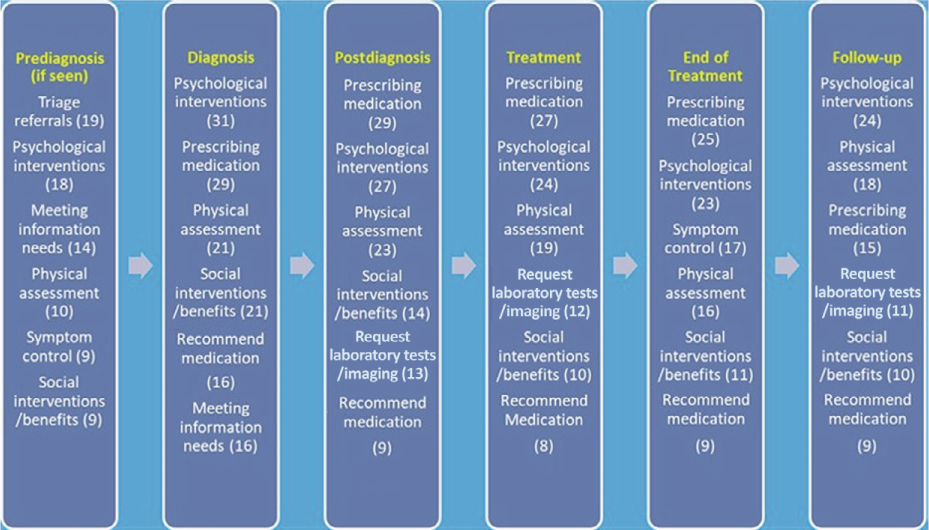

Work Left Undone

Psychological interventions, physical assessment, social interventions/benefits, and recommending or prescribing medication feature highly in respondents’ work undone, as summarized in Figure 2.

Most common areas of intervention left undone at each treatment pathway stage

Time Spent on Benefits Claims

Respondents were asked how long they spent, on average, each week dealing with a variety of benefits that patients with MS might claim (Universal Credit, Personal Independence Payments [PIPs], Attendance Allowance, Employment and Support Allowance, Carers Allowance, and “other”). Of the 148 respondents who spent time on benefits claims in general, 132 spent at least some time on PIPs, 96 on Employment and Support Allowance, 64 on Carers Allowance, 63 on Attendance Allowance, and 44 on Universal Credit; 35 reported spending some time on other benefits (Figure S4).

Free-Text Responses: Themes and Quotations

Several themes emerged from analysis of the 48 free-text responses received. Writing reports and letters of support were mentioned 19 times, with a typical example being a “support letter for employers and early retirement on health grounds. Also for grant applications and continuing care assessments.”

Eight responses concerned being unable to write reports or letters of support either through lack of time or being informed not to by their Trust, eg, “I do not assist in writing reports for PIP and other benefits at this time due to the size of the caseload.”

Regarding referring patients with MS to other agencies for support with benefits, nine comments mentioned the Citizen’s Advice Bureau (CAB); four, charity-supplied advisors; and two, social workers. The following is a typical example: “I will write reports when asked from relevant agency. We work closely with MS society who pay for a CAB advisor to be available one day a week at the MS therapy centre to discuss all these issues and to help individuals complete forms, plus support them through the appeal process if needed. This is an invaluable service and relieves the nursing service of a significant amount of workload.”

Comments also raised the topic of distress and anxiety caused by PIP, for example, “Rolling out PIP in my area so have had marked increase in requests to assist with form filling, providing evidence, requests for a review and dealing with anxiety caused by the process.”

Other similar issues that took up respondents’ time and were mentioned in comments included MS grants, support at work, Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency and Blue Badge requests (UK disabled parking scheme), issues related to education, and housing adaptations.

Discussion

It has been demonstrated that specialist disease-specific nurses can enhance both the quality of care received by patients and the overall patient experience.19,20 Such specialist nurses can not only improve the quality of care but may also demonstrate improvements in efficiency measured by markers such as preventing unnecessary admissions to an acute inpatient unit.14,21 In common with any supply model, it is probable that there is a point of saturation at which the quality of the service is at least partly driven by workload distribution, which can result in work being left undone.22

There are some limitations to the study, including obtaining data from a self-selecting group via an online survey, reliance on a priori data from workers outside the MS specialty, and that the model was a retrospective “one point in time” model and relates only to the situation encountered by respondents. If the respondents’ workload radically changes, this model will have reduced reliability.

The spread of respondents throughout the United Kingdom is similar to that found in the recent MS Trust Nurse Mapping Survey, which reported that 81.5% of FTE MS nurses were in England, 10.8% in Scotland, 4.8% in Wales, and 2.9% in Northern Ireland.23

Some respondents reported caseloads of 2000 or more patients. There are several possible reasons for the high caseloads reported by these respondents. Vacancies for MSSN staff may be one such cause. Vacant positions were estimated to be equivalent to 35 FTE in this study, potentially resulting in increased caseloads for nurses with vacancies in their team. A second factor is the level of unpaid overtime reported by respondents. Only 17% of respondents reported that they regularly performed no unpaid overtime. For respondents who did report performing unpaid overtime, the total amount was estimated at the equivalent of 17.2 FTE.

Workload analysis shows that there is wide variation in workload and that there are a variety of levels of service provision delivered by respondents. The group recorded 1547 sessions that were taken up with programmed clinical activity. Most of this time related to a telephone advice line (565 [36%]) and nurse-led clinics (389 [25%]).

As a result, it is important to take into account this variability of service provision and to include local factors, including issues like the provision of administrative support. In other specialties, it has been demonstrated that providing assistance to specialist nurses, such as administration and support workers, can result in an increase in productivity, allowing the specialist nurses to manage their caseloads proactively, with reduced emergency admissions as an outcome.24 The range of complexity of patients is another local factor that can influence caseloads.

The amount of time spent by MSSNs on benefits claims for patients with MS seems to be significant, with all of the various UK benefits examined in the study taking up MSSN time. Anecdotal evidence from the analysis of the free-text comments suggests that there are other social issues, such as interaction with the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency regarding the ability to drive, Blue Badge applications (see Results), reports required by employers, housing, and education, all adding to the MSSN workload.

The previous work by the MS Trust cited a recommended caseload of 358 people with MS per FTE MSSN. Anecdotal evidence from the MSSN population indicates that caseload and workload are increasing. In terms of caseload, one reason for this increase could be that the data are underestimating the population. It is surprising that, to date, there is no accepted accurate figure for the number of people with MS in the United Kingdom, and this is an area that requires further investigation. Anecdotally, there are also changing demands on the system, which, along with population increase, are likely driving workload increases. The drug regimens are becoming more complex with greater risks, and, as a result, people with MS require more complex monitoring; structural and societal issues such as changes to the benefits system are also causing an increase in workload.

At the current recommended caseload range, a considerable amount of work is left undone. This is particularly so of psychosocial care, symptom control, and medicine management. Less than 30% of this group were independent prescribers, which leads to door hanging (see Methods). Previous work has shown that it is generally more efficient if case-managing advanced practice nurses can sign off on their own prescriptions and investigations.

A caseload closer to 315 is more realistic in terms of delivering care within this envelope, but this is not absolute and the following factors should be considered. This number is based on the average for the group. Five percent to 10% of the caseload is complex and requires approximately 30% of the available time. More complex caseloads, for example, more comorbidity, symptom control issues, or very high psychosocial needs, should be adjusted to reflect this. If such patients (requiring ≥2 hours a week of MSSN time) are more than 10% of the caseload, the number should be adjusted downward proportionally.

In conclusion, given that the work left undone is considerable, the complexity of work has increased, and the caseload is mixed, the original recommendation of 358 people with MS is, on average, too high to optimally manage care. Factors such as travel time, access to psychological care, complexity of caseload, changing drug therapies, and societal issues such as the benefits system contributed to driving demand/workload.

PRACTICE POINTS

The work of MS specialist nurses in the United Kingdom is complex and is the principal means of case management in the care of people with MS.

There is no simple number in terms of optimum caseload because the workload is variable depending on a variety of factors.

The current recommended UK caseload of 358 people with MS per full-time equivalent seems to be too high, with a considerable amount of work left undone. This caseload recommendation has been revised downward to 315.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank those who took part in data collection and in the consensus-building process that led to the production of the study: Jacki Smee, Helen Owen, Mary Fraser, Esther Cockram, Jane Metcalfe, Carolyn Cairns, Fiona Mullen, Jenny Pye, Bethan Tredwell, Mary Fraser, and Carmel Wilkinson; the members and secretariat of the UK Multiple Sclerosis Specialist Nurse Association; and Delia Britter for her help with organization of the project.

References

Hall LE. Nursing: what is it? Can Nurse. 1964; 60: 150– 154.

Pitkaaho T, Partanen P, Miettinen M, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. Nonlinear relationships between nurse staffing and patients’ length of stay in acute care units: Bayesian dependence modelling. J Adv Nurs. 2015; 71: 458– 473.

Ebright PR, Patterson ES, Chalko BA, Render ML. Understanding the complexity of registered nurse work in acute care settings. J Nurs Adm. 2003; 33: 630– 638.

Raiborn CA. Managerial Accounting . Nelson Thomson Learning; 2004.

Prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Trust website. Accessed April 2018. https://www.mstrust.org.uk/a-z/prevalence-and-incidence-multiple-sclerosis

Mackenzie IS, Morant SV, Bloomfield GA, . Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the UK 1990 to 2010: a descriptive study in the General Practice Research Database. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014; 85: 76– 84.

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES). NHS Digital website. Accessed November 2018. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/data-tools-and-services/data-services/hospital-episode-statistics

Modelling sustainable caseloads for MS specialist nurses. Multiple Sclerosis Trust website. Published November 2014. Accessed April 2018. https://support.mstrust.org.uk/shop#browse

Leary A, Brocksom J, Endacott R, . The specialist nursing workforce caring for men with prostate cancer in the UK. Int J Urological Nursing. 2016; 10: 5– 13.

Kentischer F, Kleinknecht-Dolf M, Spirig R, Frei IA, Huber E. Patient-related complexity of care: a challenge or overwhelming burden for nurses - a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018; 32: 204– 212.

Punshon G, Endacott R, Aslett P, . The experiences of specialist nurses working within the uro-oncology multidisciplinary team in the United Kingdom. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017; 31: 210– 218.

Leary A, Anionwu EN. Modeling the complex activity of sickle cell and thalassemia specialist nurses in England. Clin Nurse Spec. 2014; 28: 277– 282.

Leary A, Mason I, Punshon G. Modelling the inflammatory bowel disease specialist nurse workforce standards by determination of optimum caseloads in the UK. J Crohns Colitis. 2018; 12: 1295– 1301.

Quin D. A collaborative care pathway to reduce admission to secondary care for multiple sclerosis. Br J Neurosci Nurs. 2011; 7: 497– 499.

National Cancer Action Team. The Alexa Toolkit: Calculating Optimum Caseload Guidance for Lung Cancer Nurse Specialists. London, UK: Department of Health; 2013.

Oliver S, Leary A. The value of the nurse specialist role: Pandora initial findings. Musculoskelet Care. 2010; 8: 3,175– 177.

Courtney M, Carey N, Stenner K. An overview of non-medical prescribing across one strategic health authority: a questionnaire survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012; 12: 138.

Anderson R. Thematic Content Analysis: Descriptive Presentation of Qualitative Data. Institute of Transpersonal Psychology; 1997.

National Cancer Patient Experience Survey Programme: 2012 National Survey Report . London, UK: Department of Health; 2012.

HSJ Workforce. Time for some advanced thinking? the benefits of specialist nurses. Published February 2015. Accessed December 2017. https://www.hsj.co.uk/Uploads/2015/02/25/f/c/y/HSJ-Workforce-Supplement-150227.pdf

Baxter J, Leary A. Productivity gains by specialist nurses. Nurs Times. 2011; 107: 15– 17.

Ball J, Murrells T, Rafferty AM, Morrow E, Griffiths P. Care left undone during nursing shifts: associations with workload and perceived quality of care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014; 23: 116– 125.

Hannan G, Sopala J, Roberts M. MS specialist nursing in the UK 2018: results from the 2018 MS Trust Nurse Mapping Survey. MS Trust website. Published October 2018. Accessed November 2018. https://www.mstrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/Nurse%20Mapping%202018%20WEB.pdf

Leary L, Quinn D, Bowen A. Impact of proactive case management by multiple sclerosis specialist nurses on use of unscheduled care and emergency presentation in multiple sclerosis: a case study. Int J MS Care. 2015; 17: 159– 163.