Publication

Research Article

Identifying Barriers to and Facilitators of Health Service Access Encountered by Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

CME/CNE Information

Activity Available Online: To access the article, post-test, and evaluation online, go to https://www.highmarksce.com/mscare.

Target Audience: The target audience for this activity is physicians, physician assistants, nursing professionals, mental health practitioners, rehabilitation therapists, and other health care providers involved in the management of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Learning Objectives:

1) Identify several specific barriers and facilitators encountered by people with MS when attempting to access health care services, which the learner should consider in their clinical practice.

Accreditation Statement:

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and Delaware Media Group. The CMSC is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Physician Credit: The CMSC designates this journal-based activity for a maximum of 0.75 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Nurse Credit: The CMSC designates this enduring material for 0.75 contact hour (0.0 in the area of pharmacology).

Disclosures: Francois Bethoux, MD, Editor in Chief of the International Journal of MS Care (IJMSC), has served as Physician Planner for this activity. He has disclosed relationships with Springer Publishing (royalty), Qr8 (receipt of intellectual property rights/patent holder), Biogen (receipt of intellectual property rights/patent holder, speakers’ bureau), GW Pharma (consulting fee), MedRhythms (consulting fee, contracted research), Genentech (consulting fee), Helius (consulting fee), and Adamas Pharmaceuticals (contracted research). Laurie Scudder, DNP, NP, has served as Reviewer for this activity. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Chantel D. Mayo, MSc, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Negar Farzam-kia, BSc, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Setareh Ghahari, PhD, OT Reg (Ont), has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The peer reviewer for IJMSC has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The staff at IJMSC, CMSC, and Delaware Media Group who are in a position to influence content have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Note: Financial relationships may have changed in the interval between listing these disclosures and publication of the article.

Method of Participation:

Release Date: February 1, 2021

Valid for Credit Through: February 1, 2022

In order to receive CME/CNE credit, participants must:

1) Review the continuing education information, including learning objectives and author disclosures.

2) Study the educational content.

3) Complete the post-test and evaluation, which are available at https://www.highmarksce.com/mscare.

Statements of Credit are awarded upon successful completion of the evaluation and the post-test with a passing score of >70%. The post-test may be retaken if necessary. There is no fee to participate in this activity.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use: This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not approved by the FDA. The CMSC and Delaware Media Group do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of the CMSC or Delaware Media Group.

Disclaimer: Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any medications, diagnostic procedures, or treatments discussed in this publication should not be used by clinicians or other health care professionals without first evaluating their patients’ conditions, considering possible contraindications or risks, reviewing any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparing any therapeutic approach with the recommendations of other authorities.

Abstract

Background:

The symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS) can be diverse, complex, and progressive, creating a need for frequent and long-standing health care services. The purpose of this scoping review was to identify the barriers people with MS encounter when attempting to access multidisciplinary health services and the reported facilitators for better access to health services.

Methods:

The MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL databases were searched, without date or geographic restrictions, using the following terms: multiple sclerosis, health services accessibility, health care access, health care delivery, and delivery of health care. After screening based on exclusion criteria, 23 articles were included in the final review.

Results:

Five main themes were identified as barriers and facilitators to accessing health services: 1) information (information available to people with MS, health care provider knowledge of and familiarity with MS), 2) interactions (interactions between health care providers and people with MS, social networks and support of people with MS, collaboration among health care providers), 3) beliefs and skills (personal values and beliefs, perceived time to travel to and attend appointments, and self-assessment of symptoms and needs of people with MS), 4) practical considerations (wait times, physical barriers, affordability of services), and 5) nature of MS (complexity and unpredictability of disease symptoms).

Conclusions:

People with MS and their health care providers may benefit from structured and comprehensive MS-specific education to address barriers to accessing health care services. The education can ultimately facilitate the process of addressing unmet health care needs and contribute to a greater quality of life for people with MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) symptom presentation can be diverse, with an unpredictable disease course, creating a need for frequent and long-standing health care services from a variety of health care professionals, including physicians, physical and occupational therapists, and mental health professionals.1–3 Despite frequent interactions with health care providers, people with MS continue to report unmet health care needs and dissatisfaction with aspects of their current level of care.4–6 Among these reports are concerns regarding discontinuity of care, lack of information about diagnosis and symptom management, and lack of patient-centered care. Indeed, unmet health care needs can contribute to ongoing MS symptoms, resulting in physical, psychosocial, and occupational consequences for people with MS.1

To promote patient-centered care, target improved health service access, and, ultimately, improve quality of life (QOL), it is essential to identify the unique barriers contributing to health care service access for individuals with MS. It is also helpful to identify how existing aspects of care may facilitate access to health services. This knowledge is critical as research has demonstrated that removing barriers to MS physical and mental health care contributes to improved health-related QOL for people with MS.7

The objective of the present study was to conduct a scoping review of the current literature to identify both the specific barriers that individuals with MS encounter when attempting to access multidisciplinary health services and the reported facilitators of improved access to health services.

Methods

Guidelines outlined by Arksey and O’Malley8 and subsequent recommendations by Levac and colleagues9 guided the methods for this scoping review. In brief, the research question and search strategy were developed, relevant articles were identified and selected according to exclusion criteria, data were extracted and charted, and main themes were identified, as described herein.

Search Strategy

The search was guided by the research question, “What are the barriers to and facilitators of health service access for individuals with MS?” Three databases were searched: MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL. Search terms included multiple sclerosis, health services accessibility, health care access, health care delivery, and delivery of health care. Studies were considered up to July 23, 2018, the date the final database search was conducted.

Inclusion and Exlusion Criteria

A total of 857 citations were exported to a reference manager (EndNote; Clarivate), and 156 duplicates were removed. The remaining 701 abstracts were reviewed for inclusion (see the exclusion criteria below), and from these, 73 articles were downloaded for further full-text review (Figure S1, published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org).

Articles were excluded if 1) no specific barriers to or facilitators of health service access were identified by the research, 2) participants involved combined neurologic groups wherein MS-specific results were not presented separately, 3) the participants spoke about a health behavior (eg, exercise) rather than about accessing a health service (eg, physiotherapy), 4) the text was written in a language other than English or French, and/or 5) no full-text article was available for review. There were no date or geographic restrictions for inclusion.

Data Extraction and Identification of Main Themes

Based on the study criteria, 23 articles were ultimately included in the present review. For each of these articles, characteristics of the study population (eg, number of participants, age, MS subtype) and study design (eg, qualitative vs quantitative) were tabulated, along with the specific barriers and facilitators reported by study participants. Next, the extracted information about barriers and facilitators was grouped by independent reviewers (C.D.M. and N.F.) to identify the main themes described later herein. A third reviewer (S.G.) was consulted to resolve discrepancies, when needed. When multiple barriers and/or facilitators were reported in a single study, the results were grouped into more than one theme.

Results

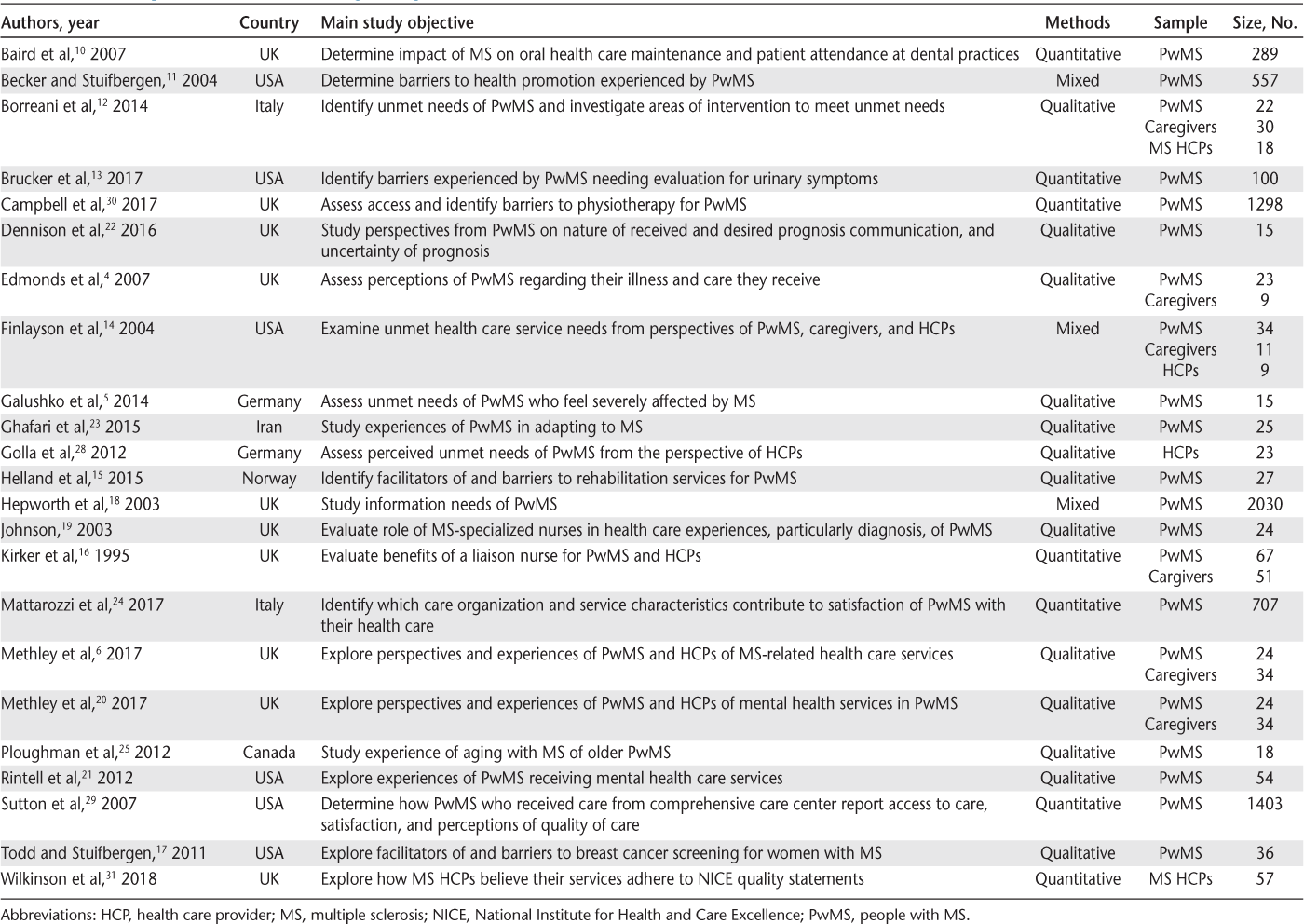

After final examination, seven quantitative, 13 qualitative, and three mixed qualitative and quantitative studies were included in this scoping review, for a total of 23 articles (Table 1). Studies were included in this review only if specific barriers and/or facilitators to accessing health care services were identified. These barriers and facilitators were categorized into five major themes: information, interactions, beliefs and skills, practical considerations, and the nature of MS (Figure S2). Findings in each theme were further grouped into several subthemes.

Summary of selected articles regarding barriers to and facilitators of health service access in MS

Information

The first theme, information, concerned the availability of MS-specific information to people with MS and health care provider knowledge of and familiarity with MS.

Information Available to People with MS

Lack of information regarding services available to people with MS was cited by nine distinct studies as a significant barrier to accessing health care services.4,10–17 Services cited in these studies had a wide range and varied from MS-specific dental services10 to care for lower urinary tract symptoms13 and rehabilitation.15 Three studies found that lack of information about physical aids, adaptations, and insurance/welfare benefits posed a barrier to accessing care.4,12,17 In addition, understanding how the health care system operates, knowing how to navigate it, and knowing how to fill out necessary paperwork were identified as facilitators.14

Health Care Provider Knowledge of and Familiarity with MS

Seven studies highlighted that health care provider knowledge of MS-specific information influences how people with MS access health care services.5,6,16,18–21 For instance, one study found that some people with MS had difficulties finding family doctors and neurologists who they perceived to be competent and knowledgeable about novel therapies.5 Finding a mental health care provider who is a “good fit” and is knowledgeable about MS is another barrier that people with MS face.21 Many study participants found educating their mental health care provider about MS exhausting and frustrating, causing one participant to stop seeking further treatment altogether.21 General practitioners and nurses both highlighted a lack of training and education with respect to new treatment options and mental health needs of people with MS, respectively, as barriers to providing care.6,20

One study found that increasing awareness of available services for both people with MS and health care providers was helpful in decision making concerning candidacy for available services.6 Nurse liaisons were noted in one study as important in this regard.16 That is, nurse liaisons improved knowledge of MS for both people with MS and affiliated health care professionals; in addition, they recognized overlooked symptoms and improved health care access for people with MS by increasing referrals to needed services.16 Liaison nurses, as well as specialist nurses and clinical nurse practitioners, may perform many tasks that are key to a patient’s health management plan. They give information and advice to patients and their families and coordinate different aspects of the health care plan.16

Interactions

The second theme, interactions, encompassed the interpersonal relationships and communication that affect access to health care services for people with MS. Three subthemes were identified: 1) interactions between health care providers and people with MS, 2) collaboration among health care professionals, and 3) social networks and support.

Interactions Between Health Care Providers and People with MS

Nine distinct studies identified barriers and facilitators that lend to this subtheme.6,11,16,17,21–25 The importance of interactions between health care providers and people with MS was highlighted by two studies. For example, negative interactions with health care professionals (described as “highly emotive”) affected how people with MS accessed health care services for years.6 People with MS also noted that ineffective listening and communication by their health care providers contributed to “unhelpful care.”25

Poor communication and rapport with health care providers during diagnosis that results from a lack of understanding or empathy affected health service access.17,22,23 A distressing diagnostic experience negatively affected future interactions with health professionals22 and how people with MS follow prescribed treatments, both of which pose a significant barrier to accessing health care services.23 Feeling rushed during consultations with health care providers and feeling that providers did not have time for them contributed to poor communication and was a barrier to health care access.16,25 Research shows that having a nurse with whom to discuss sensitive topics and practical issues facilitated access to various services.16,22

Collaboration Among Health Care Professionals

Although open and effective communication between members of an interprofessional health care team is important for continuity of care,26,27 lack of communication and coordination between health care professionals is a barrier to health service access.4,6,28 Lack of continuity of care causes frustration for people with MS and even leads to certain health concerns not being addressed by health care providers despite repeated attempts by people with MS reiterating the concern.4 Similarly, inadequate communication causing poor continuity of care can lead to loss of information and treatment plans being abandoned.28 Seeking care at a comprehensive care center or an MS clinical center, where various services and health care providers are integrated, facilitated access to health care services.21,29 For instance, people with MS found it easier to access mental health services via these clinics.21

Social Networks and Support

Three studies found that social isolation and lack of support from family and friends was a barrier to accessing health care services for people with MS.11,14,30 Similarly, having supportive family members and friends nearby to help maintain health care routines, such as attending doctor appointments, was found to be a facilitator to health care access.14,28 These data illustrate the importance of a strong social network to ensure continuous access to health care services.

Beliefs and Skills

The third theme, beliefs and skills, involved the perceptions of individuals with MS. Three subthemes were identified: 1) personal beliefs, 2) perceived time, and 3) self-assessment skills.

Personal Beliefs

Lack of confidence in one’s abilities or appearance, and feeling embarrassed, was found to be a barrier to accessing health care services for people with MS in two studies.11,17 Fears of being confronted with the realities of MS symptom progression and of being labeled as a patient with MS were also barriers to seeking health services such as rehabilitation.15 In addition, believing that a particular health intervention would not have a positive effect was cited as a barrier.11 Correspondingly, a positive attitude and being accepting of one’s physical limitations contributed to greater health service utilization by individuals with MS.14 These findings demonstrate the importance of addressing the beliefs and concerns of individuals with MS to overcome these barriers.

Perceived Time

This subtheme relates to the mindset of people with MS. Four studies found that believing that people with MS do not have sufficient time, or already have too many responsibilities and commitments, posed a barrier to people with MS to access health care services.11,13,15,17 For instance, one of the main barriers to seeking urologic care was feeling that “they had enough problems to deal with,” as voiced by 18.6% of people with MS included in one study.13 Another study found that many people with MS did not use services at rehabilitation facilities for which they were eligible due to time restrictions and existing commitments.15 The need for personalized, feasible care plans for people with MS to improve access to care was highlighted by the literature.

Self-assessment Skills

Self-assessment is considered the ability to assess changes and medical needs to seek out appropriate health care services. Four studies found that an inability to identify needs or a misidentification of symptoms by people with MS posed a barrier to accessing health care services.6,12,14,20 For instance, determining the cause of low mood and whether it required mental health care intervention was difficult for people with MS.20 These findings suggest that giving people with MS tools to self-assess may improve access to required health care services.

Practical Considerations

The fourth theme, practical considerations, included systemic-level and functional factors that individuals with MS encounter when seeking health services. Three subthemes were identified among these practical considerations, including concerns regarding 1) wait times, 2) physical barriers, and 3) finances.

Wait Times

Six studies noted that long wait times, primarily to access secondary care, and a paucity of specialized therapy centers was a significant barrier to accessing health care services.6,20,21,23,25,31 People with MS noted particularly long wait times for appointments with specialists such as mental health professionals.21,25 Similarly, people with MS who participated in another study noted delays in accessing community and secondary services.6 These findings highlight a need to address wait times and availability shortages for those with MS.

Physical Barriers

Physical barriers could hinder the ability of people with MS to access health services, including lengthy commutes and/or lack of accessible transportation options, inaccessible buildings, and lack of reserved accessible parking.10,11,13,14,17,21,30 For instance, people with MS noted that stairs, heavy doors, and small changing rooms posed barriers to accessing dental services,10 mental health services,21 and breast cancer screenings.17 These barriers can, therefore, affect access to health care services that are not directly linked to MS but contribute to the overall health of people with MS.

Finances

Three studies highlighted that affordability of services was a barrier to accessing health services.11,13,21 For example, individuals with MS expressed concern about how to afford mental health services should they lose insurance benefits.21

Nature of MS

The fifth theme, the nature of MS, encompassed factors associated with MS symptoms and their complex interactions. Three studies noted that symptoms such as fatigue, pain, limited mobility, and cognitive impairment were barriers to accessing health care services.11,17,30 For example, women with MS reported being unable to tolerate standing during procedures such as mammograms.17 In addition, one study found that individuals with MS were not considered candidates for mental health service referral if their symptoms were not seen as separate mental health conditions distinct from MS.20 Thus, the complexity of MS symptoms was seen as a barrier to accessing mental health services.

Discussion

In the present study, five main themes were identified as barriers and facilitators to accessing health services for people with MS: information, interactions, beliefs and skills, practical considerations, and the nature of MS. The present findings are similar to the barriers to and facilitators of health service access reported by other patient populations with chronic conditions. For example, during cancer consultations, individuals with cancer have reported that health care providers do not provide them with sufficient information, lack empathy in their communications, and perceive that there is no time to express concerns.32 Similarly, differences in perspectives among patients and providers, insufficient time, and stroke-related impairments (eg, fatigue, cognitive impairment, dysregulated mood) are reported barriers to stroke rehabilitation, and frequent active communication and education, adequate resources, and effective and encouraging providers were facilitators.33 Similar findings were also reported for people with epilepsy; social support, knowledgeable health care providers, and adequate medical insurance were key during the diagnostic process.34 In addition, psychological barriers (eg, mental illness, frustration), cognitive impairments, mistrust of health care providers, and poor communication from health care providers posed barriers to health care self-management for these individuals.35

Overall, identifying the major barriers and facilitators experienced by people with MS is a critical first step in facilitating the changes needed to improve access to health services for people with MS. In the present study, a critical barrier to accessing health services concerned a lack of MS-specific information, for both people with MS and health care providers. Because individuals with MS reported being unaware of various services and supports available to them,17,19 and perceived that their health care providers lacked MS-specific training,5 both individuals with MS and their health care providers may benefit from structured, comprehensive MS-specific education. Research has shown that increased knowledge is necessary for disease self-management for people with MS, allowing them to be active partners in managing their chronic condition.36,37 Furthermore, studies have also highlighted the benefit of having a dedicated health care professional (eg, a nurse liaison) to help individuals with MS navigate the health care system and identify possible sources of funding, including insurance.16 In addition to consulting with health care providers, individuals with MS may wish to seek out publicly available educational resources through MS societies (eg, MS Society of Canada, National MS Society) and/or seek the assistance of an “MS navigator,” an individual trained to provide MS-specific information. Health care providers may also wish to seek out professional development opportunities (eg, MS continuing education courses), such as those available through the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC).

Another relevant barrier to accessing health services concerned the interpersonal interactions between individuals with MS and their health care providers. Some individuals with MS perceived interactions as nonempathetic, which disrupted the trust in the patient-physician relationship, leading the individual with MS to not follow their health care provider’s recommendations.23 Others felt too embarrassed to ask questions about specific concerns such as incontinence or sexual problems.16 One major solution to this ineffective interaction is targeted communication interventions. There is strong evidence that such interventions enhance communication between patients and health care providers, allowing patients to obtain greater information and have a more active role in discussions.38 Therefore, individuals with MS may benefit from specialized education about how to ask specific, relevant questions and how to better communicate their perceived needs with their health care provider. At the same time, health care providers may benefit from specific training on effective communication with their patients, including the benefits of empathetic and patient-centered practices.39,40

Several studies found that the mindset of people with MS can positively or negatively affect access to health services. An important factor identified is one’s outlook and attitude on the health service in question, and how they believe it will affect their QOL. This has been reported previously as a relevant factor affecting health care access and compliance for those with other chronic conditions, such as heart failure41 and postoperative pain management.42 One way to facilitate access to health care services for these individuals may be to provide more comprehensive patient-specific education by thoroughly discussing treatment plans and addressing any misconceptions that may exist.

The ability of a person with MS to self-assess and correctly identify their own needs affects access to health care services. It is, therefore, important to improve education by providing patients with MS with the tools they require to accurately identify and adequately communicate their needs to health care professionals. In addition, the complexity of the symptoms experienced by people with MS could pose barriers to health care access.11,17,30 Multiple sclerosis is a heterogenous disease, with different subtypes and phases, as well as a wide array of potential symptoms.43 These symptoms, including mobility issues and fatigue, greatly contribute to how people with MS access their health care services. Learning to communicate these barriers with health care professionals so that they can be addressed may improve access to health care services and enhance QOL.

Several practical matters were found to significantly affect access to health care services for people with MS. Financial and insurance-related considerations is one such factor. People with MS in several studies cited financial limitations and uncertainty of insurance coverage as a barrier to accessing health care services.11,13,21 The economic burden is great for people with MS and their loved ones owing to the effect on employment for people with MS and others in the household, as well as the cost of medications, medical services, home modifications, and items such as mobility aids.44,45 It would, therefore, be helpful to have information available for people with MS to clarify insurance options, rebates, and any other helpful resources available to alleviate financial concerns. One study has shown that assistance from a dedicated health care professional, such as a nurse liaison, can be helpful in identifying sources of financial assistance.16

Regarding limitations, this review used a language restriction (only articles in English and French were included). Further research on health care access should include health care providers and people with MS, as well as their informal caregivers, to get a comprehensive understanding of their diverse perspectives. In addition, it is necessary to optimize knowledge translation to people with MS, their loved ones, and health care providers to facilitate effective communication between these parties and ultimately improve QOL for individuals with MS. Knowledge can be drawn from studies in the context of other chronic conditions, such as cancer and type 2 diabetes.46–49

In conclusion, this scoping review of the current barriers and facilitators encountered by people with MS identified themes concerning information, interactions, beliefs and skills, practical considerations, and the nature of MS, all of which can inform potential changes in clinical practice and policy and guide future research. The results highlight that both individuals with MS and their health care providers may benefit from structured and comprehensive MS-specific education. The education can facilitate the process of addressing unmet health care needs and, ultimately, contribute to a greater QOL for people with MS.

PRACTICE POINTS

When attempting to access health services, people with MS encounter barriers related to 1) lack of information, 2) varied interactions with health care providers and social support, 3) variable beliefs and skills (eg, personal values, time constraints), 4) practical considerations (eg, physical barriers, affordability), and 5) the complex nature of MS symptoms.

People with MS and their health care providers may benefit from structured and comprehensive MS-specific education. The education can facilitate the process of addressing unmet health care needs and, ultimately, contribute to a greater quality of life for people with MS.

Acknowledgments

We thank the MS Society of Canada and the endMS Scholar Program for Researchers in Training for their support of this project.

References

Chiu C, Bishop M, Pionke JJ, Strauser D, Santens RL. Barriers to the accessibility and continuity of health-care services in people with multiple sclerosis: a literature review. Int J MS Care. 2017; 19: 313– 321.

Marrie RA, Yu N, Wei Y, Elliott L, Blanchard J. High rates of physician services utilization at least five years before multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Mult Scler. 2013; 19: 1113– 1119.

Thorne S, Con A, McGuinness L, McPherson G, Harris SR. Health care communication issues in multiple sclerosis: an interpretive description. Qual Health Res. 2004; 14: 5– 22.

Edmonds P, Vivat B, Burman R, Silber E, Higginson IJ. ‘Fighting for everything’: service experiences of people severely affected by multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 660– 667.

Galushko M, Golla H, Strupp J, . Unmet needs of patients feeling severely affected by multiple sclerosis in Germany: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2014; 17: 274– 281.

Methley AM, Chew-Graham CA, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Campbell SM. A qualitative study of patient and professional perspectives of healthcare services for multiple sclerosis: implications for service development and policy. Health Soc Care Community. 2017; 25: 848– 857.

Wu N, Minden SL, Hoaglin DC, Hadden L, Frankel D. Quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis: data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2007; 30: 233– 267.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005; 8: 19– 32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010; 5: 69.

Baird WO, McGrother C, Abrams KR, Dugmore C, Jackson RJ. Verifiable CPD paper: factors that influence the dental attendance pattern and maintenance of oral health for people with multiple sclerosis. Br Dent J. 2007; 202: E4; discussion 40–41.

Becker H, Stuifbergen A. What makes it so hard? barriers to health promotion experienced by people with multiple sclerosis and polio. Fam Community Health. 2004; 27: 75– 85.

Borreani C, Bianchi E, Pietrolongo E, . Unmet needs of people with severe multiple sclerosis and their carers: qualitative findings for a home-based intervention. PLoS One. 2014; 9: e109679.

Brucker BM, Nitti VW, Kalra S, . Barriers experienced by patients with multiple sclerosis in seeking care for lower urinary tract symptoms. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017; 36: 1208– 1213.

Finlayson M, Denend TV, Shevil E. Multiple perspectives on the health service need, use, and variability among older adults with multiple sclerosis. Occup Ther Health Care. 2004; 17: 5– 25.

Helland CB, Holmøy T, Gulbrandsen P. Barriers and facilitators related to rehabilitation stays in multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Int J MS Care. 2015; 17: 122– 129.

Kirker S, Young E, Warlow C. An evaluation of a multiple sclerosis liaison nurse. Clin Rehabil. 1995; 9: 219– 226.

Todd A, Stuifbergen A. Barriers and facilitators to breast cancer screening: a qualitative study of women with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2011; 13: 49– 56.

Hepworth M, Harrison J, James N. Information needs of people with multiple sclerosis and the implications for information provision based on a national UK survey. Aslib Proceedings. 2003; 55: 290– 303.

Johnson J. On receiving the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: managing the transition. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 82– 88.

Methley A, Campbell S, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Chew-Graham C. Meeting the mental health needs of people with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study of patients and professionals. Disabil Rehabil. 2017; 39: 1097– 1105.

Rintell DJ, Frankel D, Minden SL, Glanz BI. Patients’ perspectives on quality of mental health care for people with MS. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012; 34: 604– 610.

Dennison L, McCloy Smith E, Bradbury K, Galea I. How do people with multiple sclerosis experience prognostic uncertainty and prognosis communication? a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2016; 11: e0158982.

Ghafari S, Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Nourozi K, Mohammadi E. Patients’ experiences of adapting to multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Contemp Nurse. 2015; 50: 36– 49.

Mattarozzi K, Baldin E, Zenesini C, . Effect of organizational features on patient satisfaction with care in Italian multiple sclerosis centres. Eur J Neurol. 2017; 24: 631– 637.

Ploughman M, Austin MW, Murdoch M, Kearney A, Godwin M, Stefanelli M. The path to self-management: a qualitative study involving older people with multiple sclerosis. Physiother Can. 2012; 64: 6– 17.

Mulvale G, Embrett M, Razavi SD. ‘Gearing Up’ to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care: a systematic review and conceptual framework. BMC Fam Pract. 2016; 17: 83.

Sudhakar-Krishnan V, Rudolf MC. How important is continuity of care? Arch Dis Child. 2007; 92: 381– 383.

Golla H, Galushko M, Pfaff H, Voltz R. Unmet needs of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: the health professionals’ view. Palliat Med. 2012; 26: 139– 151.

Sutton JP, Schur C, Feldman J, Tyry T. Comprehensive care centers and treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2007; 9: 104– 110.

Campbell E, Coulter E, Mattison P, McFadyen A, Miller L, Paul L. Access, delivery and perceived efficacy of physiotherapy and use of complementary and alternative therapies by people with progressive multiple sclerosis in the United Kingdom: an online survey. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017; 12: 64– 69.

Wilkinson C, White S, Fronzo C. Are multiple sclerosis services meeting the NICE quality standard? Br J Neurosci Nurs. 2018; 14: 73– 76.

Brandes K, Linn AJ, Smit EG, van Weert JC. Patients’ reports of barriers to expressing concerns during cancer consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2015; 98: 317– 322.

Plant SE, Tyson SF, Kirk S, Parsons J. What are the barriers and facilitators to goal-setting during rehabilitation for stroke and other acquired brain injuries? a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clin Rehabil. 2016; 30: 921– 930.

Pretorius C. Barriers and facilitators to reaching a diagnosis of PNES from the patients’ perspective: preliminary findings. Seizure. 2016; 38: 1– 6.

Perzynski AT, Ramsey RK, Colon-Zimmermann K, Cage J, Welter E, Sajatovic M. Barriers and facilitators to epilepsy self-management for patients with physical and psychological co-morbidity. Chronic Illn. 2017; 13: 188– 203.

Audulv A. The over time development of chronic illness self-management patterns: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13: 452.

Knaster ES, Yorkston KM, Johnson K, McMullen KA, Ehde DM. Perspectives on self-management in multiple sclerosis: a focus group study. Int J MS Care. 2011; 13: 146– 152.

Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS, Frankel RM. Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Med Care. 2007; 45: 340– 349.

Alroughani RA. Improving communication with multiple sclerosis patients. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2015; 20: 95– 97.

Sacristan JA. Patient-centered medicine and patient-oriented research: improving health outcomes for individual patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013; 13: 6.

van der Wal MH, Jaarsma T, Moser DK, Veeger NJ, van Gilst WH, van Veldhuisen DJ. Compliance in heart failure patients: the importance of knowledge and beliefs. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27: 434– 440.

Cogan J, Ouimette MF, Vargas-Schaffer G, Yegin Z, Deschamps A, Denault A. Patient attitudes and beliefs regarding pain medication after cardiac surgery: barriers to adequate pain management. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014; 15: 574– 579.

Kister I, Bacon TE, Chamot E, . Natural history of multiple sclerosis symptoms. Int J MS Care. 2013; 15: 146– 158.

De Judicibus MA, McCabe MP. The impact of the financial costs of multiple sclerosis on quality of life. Int J Behav Med. 2007; 14: 3– 11.

Green G, Todd J. ‘Restricting choices and limiting independence’: social and economic impact of multiple sclerosis upon households by level of disability. Chronic Illn. 2008; 4: 160– 172.

Al-Qazaz H, Sulaiman SA, Hassali MA, . Diabetes knowledge, medication adherence and glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011; 33: 1028– 1035.

Gagliardi AR, Legare F, Brouwers MC, Webster F, Badley E, Straus S. Patient-mediated knowledge translation (PKT) interventions for clinical encounters: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2016; 11: 26.

Glenn LE, Nichols M, Enriquez M, Jenkins C. Impact of a community-based approach to patient engagement in rural, low-income adults with type 2 diabetes. Public Health Nurs. 2020; 37: 178– 187.

Tricco AC, Ashoor HM, Cardoso R, . Sustainability of knowledge translation interventions in healthcare decision-making: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2016; 11: 55.