Publication

Research Article

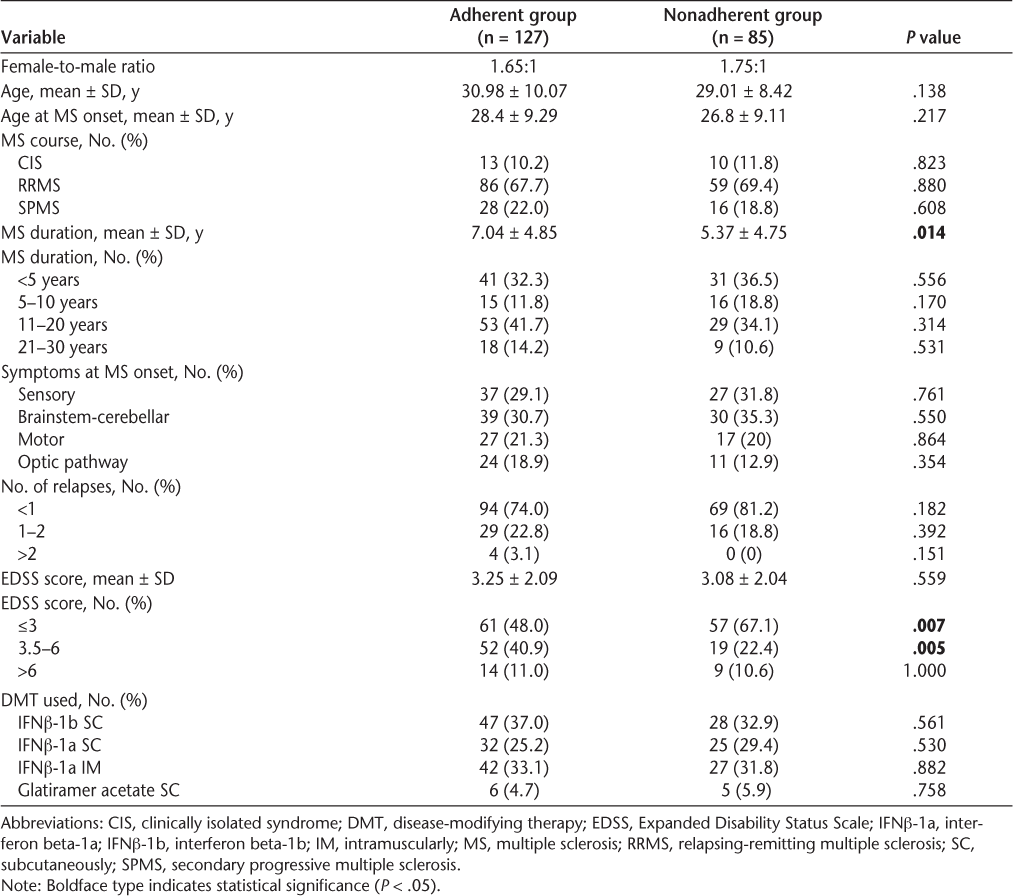

International Journal of MS Care

Adherence to First-Line Disease-Modifying Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis in Kuwait

The aim of this retrospective study was to determine the rate of nonadherence to disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) among multiple sclerosis (MS) patients in Kuwait and to identify reasons for patient discontinuation of long-term therapy. Using a newly established MS registry at our institution, we collected data on MS patients' demographics, clinical characteristics, disability measures, and continuation or discontinuation of first-line DMTs. Reasons for nonadherence were divided into four categories: adverse events, inconvenience, perceived lack of efficacy, and physician-documented disease progression. Of 212 eligible patients, 40.1% were found to be nonadherent to first-line DMTs. In the nonadherent group, the female-to-male ratio was 1.75:1 and the mean age at disease onset was 26.8 years. Of this group, 69.4% of patients had a relapsing-remitting course, 18.8% had a secondary progressive course, and 11.8% had clinically isolated syndrome. Compared with the adherent group, the nonadherent group had a shorter mean disease duration (P = .014) and a greater likelihood of having Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores of 3 or lower (67.1% vs. 48.0%; P = .007). Inconvenience was the most common reason for nonadherence (32.9%), followed by perceived lack of efficacy (25.9%), adverse events (23.5%), and physician-documented disease progression (17.7%). In summary, the rate of nonadherence to first-line DMTs in MS patients at our institution is considered high. Most nonadherent patients had a short disease duration and low EDSS scores. Inconvenience and perceived lack of efficacy were the most common reasons for nonadherence. The results demonstrate a need to improve treatment adherence among MS patients in Kuwait through providing better patient education, improving communication between patients and health-care providers, defining therapy expectations, and instituting new therapeutic techniques.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurologic disorder of the central nervous system resulting in significant long-term disabilities. The relapsing-remitting type (RRMS) is the most common at presentation, and several first-line disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) have shown significant benefit in preventing relapses and slowing disease progression among these patients. All first-line DMTs used in Kuwait are injectable, either subcutaneously (SC) or intramuscularly (IM). Adherence to treatment varies over the course of the disease. The terms adherence and compliance are often used interchangeably among physicians. According to the World Health Organization, however, a slight difference in meaning exists: Adherence to therapy is defined as the extent to which a person's behavior—taking medications, following a diet, and/or maintaining a certain lifestyle—corresponds with recommendations of a health-care provider. It is an active decision-making process. On the other hand, compliance is defined as the ability and willingness to follow a prescribed drug regimen and is considered one factor in adherence.1 2 Adherence to long-term therapy has always been a problem with various chronic diseases. The high rates of discontinuation of long-term therapy among patients with diabetes and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection have been well documented.3 4 Discontinuation rates as high as 40% for first-line DMTs have been reported in the MS population.5–9 Adverse effects, inconvenience, perceived lack of efficacy, anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment are among the many factors that may hinder adherence to therapies, in both the short and the long terms.6 10–14 The aim of this study was to determine the proportion of patients discontinuing first-line DMTs and to identify the reasons for nonadherence.

Methods

This study relied on a database for MS patients that was established at Amiri Hospital in Kuwait City in June 2010. The Amiri MS clinic is one of three MS referral centers in Kuwait. The MS registry was the first of several disease-specific registries established at the hospital in response to the increasing awareness of major neurologic conditions and the need for more epidemiological studies in Kuwait.

As part of the registry data entry procedure, each new patient presenting to the MS clinic was asked to complete a questionnaire prior to the initial interview with a neurologist. The questionnaire was in Arabic, because the patients were native speakers of Arabic. It contained questions about the use of first-line DMTs, including indication, dosage, frequency, adherence, side effects, reasons for discontinuation, and ways to decrease non-adherence. The patient was then interviewed and examined by the treating neurologist. Issues related to adherence were clarified and addressed by both the treating neurologist and the clinical nurse. The interview took between 45 and 60 minutes. Patients who were diagnosed with MS according to the 2005 revised McDonald criteria15 and had been on first-line DMTs for at least 1 year were included in the study. Demographic, clinical, and treatment data were collected for these patients, including age, gender, age at disease onset, disease duration, MS course, number of relapses in the preceding year, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score at the last visit, first-line DMT used, and reason for discontinuation. A relapse was defined as the occurrence, recurrence, or worsening of symptoms of neurologic dysfunction lasting at least 24 hours and usually ending with partial or complete remission. First-line medications included interferon beta-1a (IFNβ-1a) SC, interferon beta-1b (IFNβ-1b) SC, IFNβ-1a IM, and glatiramer acetate. Reasons for discontinuation were divided into four categories: adverse events, inconvenience, perceived lack of efficacy, and progression of the disease.

Medical records were examined carefully to verify the accuracy of the diagnosis. Patients with incomplete data, an unconfirmed MS diagnosis, severe cognitive impairment or dementia, psychiatric comorbidities such as severe depression, and use of multiple injectable drugs were excluded from the study. In addition, patients with primary progressive MS were excluded because there are no approved DMTs for this condition at present. Consent was obtained from all patients to use their data for research purposes as part of participation in the MS registry. The local hospital ethics committee granted approval to conduct this observational study.

Data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Differences between the adherent and nonadherent groups in age at MS onset, disease duration, and EDSS score were assessed with the unpaired t test. Differences between the two groups in MS course, number of relapses, symptoms at disease onset, and use of specific DMTs were assessed by means of the two-tailed Fisher exact test. The level of statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

A total of 257 patients were considered for participation in the study. Of these, 45 patients were excluded based on the study exclusion criteria. Of the remaining 212 patients, 85 (40.1%) stopped their first-line DMTs. Details of the demographics and baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. In the nonadherent group, the female-to-male ratio was 1.75:1 and the mean ± SD age at disease onset was 26.8 ± 9.11. Of this group, 69.4% (59 patients) had a relapsing-remitting course, 18.8% (16 patients) had a secondary progressive course, and 11.8% (10 patients) had clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). Compared with the adherent group, patients who stopped their DMTs had a shorter mean disease duration (5.37 vs. 7.04 years; P = .014). However, no statistically significant differences were found between the two groups when disease duration was broken into categories spanning 5 or 10 years (Table 1). A significantly higher proportion of patients in the nonadherent group had an EDSS score of 3 or lower (67.1% vs. 48.0%; P = .007), while a significantly higher proportion of adherent patients had an EDSS score between 3.5 and 6 (40.9% vs. 22.4%; P = .005). The distribution of EDSS scores at the last visit for patients who discontinued their first-line DMTs is shown in Figure 1.

Distribution of Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores at last visit of patients who discontinued their first-line disease-modifying therapies

Demographics and baseline characteristics of the study population

The discontinuation rate was relatively similar across all first-line DMTs except glatiramer acetate (Table 1). The reasons for discontinuation in our cohort are shown in Figure 2. A total of 32.9% of the nonadherent patients stopped the first-line DMT because of inconvenience, while 25.9% stopped because of perceived lack of efficacy. Adverse events resulting in intolerability were reported by 23.5%, with side effects including pain at the injection site, flu-like illness, and headaches. Finally, 17.7% of patients stopped their DMT when they were told that their disease had entered a progressive phase and DMTs were unlikely to show any beneficial effects.

Reasons for discontinuation of various disease-modifying therapies

Discussion

Multiple sclerosis is one of many chronic illnesses found among people in Kuwait. The leading causes of morbidity in the country are hypertension and diabetes.16 Almost all residents younger than 40 years are literate, with virtually no difference between the sexes. People with higher levels of education are likely to have greater awareness of risk factors for chronic illnesses and may be better able to reduce the impact of such risk factors on their health. Sabri et al.17 reported an association between hypertension and illiteracy in a study involving adults aged 20 to 65 years in Al-Ain City, United Arab Emirates. In an observational study conducted through a series of questionnaires administered to diabetic patients in Kuwait, Serour et al.18 reported that unwillingness, improper eating habits at social gatherings, lack of time, and adverse weather conditions were the main barriers to compliance with diet and exercise programs. This shows that cultural and environmental factors may have significant impacts on patients' adherence to therapeutic regimens in Kuwait. As awareness of various chronic conditions has increased, the social understanding of chronic illness has evolved into a more practical definition. Patients with chronic illnesses are increasingly understanding that treatment is not curative and the best currently available approach is close monitoring and careful management to help ensure that the condition does not worsen.

Adherence is considered an important factor in obtaining the full benefit of the approved DMTs for MS. Injectable first-line DMTs including IFNβ (IFNβ-1a SC, IFNβ-1b SC, IFNβ-1a IM) and glatiramer acetate have been shown in randomized placebo-controlled trials to reduce relapse rates and disease progression among patients with RRMS and CIS.19–26 Interferon beta-1b SC has been shown to delay sustained neurologic deterioration in patients with secondary progressive MS (SPMS).27 Effective communication between the MS patient and the prescribing neurologist is essential in making decisions regarding the initiation and continuation of DMTs. In Kuwait, interferons are widely used in RRMS and CIS, while glatiramer acetate is used in only a few hospitals because of prescribing limitations by regulatory bodies. Many neurologists in Kuwait continue to use IFNβ-1b SC in SPMS, except during active progression, when mitoxantrone or other immunosuppressants may be indicated. Escalating therapy with monoclonal antibodies such as natalizumab is used in a subset of patients in whom the disease remains active despite adequate adherence to first-line DMTs. A discussion of adherence to natalizumab is beyond the scope of this article.

The MS database established recently in our hospital to improve disease surveillance allows improvement of the quality of patient care. Important clinical and therapeutic information can be extracted from the registry. Determining the rate of adherence to DMTs was especially important because this analysis could help identify factors that might affect disease progression. The overall rate of nonadherence in our study population of 212 patients was 40.1%. Women were more likely than men to discontinue their DMTs, and a significant proportion did so after having the disease for more than 10 years. These findings are consistent with those reported in several studies in the international literature. Portaccio et al.28 evaluated 255 RRMS patients, with a mean follow-up duration of 4.2 years. Of the 255 patients, 46% suspended therapy. In a Canadian retrospective study, 39% of patients followed for at least 3 years stopped their DMTs prematurely.29 On the other hand, other studies have found lower rates of nonadherence. In a multicenter observational study, 25% of 2647 patients were nonadherent to therapy, with an average treatment duration of 31 months.9 A recent Swedish retrospective study evaluating 259 MS patients found that 15% stopped interferon therapy and that those in the non-adherent group had a longer disease duration before starting therapy than those in the adherent group (P = .002).30

In our study, patients with a relapsing-remitting course were most likely to discontinue their first-line DMTs. However, this finding may have been influenced by several factors. First, patients with CIS and SPMS made up only small percentages of the study population. Second, the relapse rate in our cohort was relatively low, with 81.2% of the nonadherent group having less than one relapse in the preceding year. Disease remission may have influenced patients to stop their DMTs because they perceived that the therapy was unnecessary. On the contrary, the beneficial effect of the therapy may have rendered the disease inactive, explaining the high rate of remission. In a study of 632 MS patients with a mean follow-up time of 47.1 months, Río et al.8 found that adherence was worse in patients with SPMS, with 30% of SPMS patients stopping DMTs, compared with only 13.5% of RRMS patients. The authors also noted that RRMS patients who stopped therapy had more active disease.

In our study, more than 50% of the nonadherent patients had a disease duration of 10 years or less, which may explain the higher proportion of RRMS patients in the nonadherent group. The short disease duration might also explain why the majority of patients in the nonadherent group (67.1%) had an EDSS score of 3 or below. Our figures differ from the findings of most data recently published in the international literature. In a retrospective evaluation of 2648 patients, Devonshire et al.9 reported that adherent patients had a significantly shorter disease duration (P < .001) and a shorter duration of therapy (median, 6.0 years) than nonadherent patients. In a multicenter observational study of 78 patients, Treadaway et al.31 reported a higher adherence rate for MS patients with a disease duration of less than 3 years (P = .0185). In other reports, high EDSS score was considered a main factor predicting interruption of therapy.8 30 Studies of adherence to MS therapy in clinical practice have shown that patients are more likely to discontinue DMTs within the first 6 months after initiation of treatment.5 29 This was also observed in our cohort, indicating that regular patient support during this time may be particularly important. The high discontinuation rate in association with short disease duration and low EDSS score in our cohort is of concern and calls for action. Several factors could have influenced the nonadherence rate in this subgroup. Patient education and awareness of the impact of the disease, patient-physician interaction and discussion when initiating DMTs, and continuous patient support are critical pillars of improved adherence.

Regarding reasons why patients discontinued their DMTs, we found that a total of 32.9% of the patients in our cohort stopped their first-line DMTs because of inconvenience. Not feeling like taking the medication, needle phobia, anxiety, and the absence of someone to help administer the injection were among the specific reasons cited. Other factors were the route of administration and the frequency of the dosing schedule. Devonshire et al.9 found that approximately 38% of 643 nonadherent patients reported reasons such as being tired of performing injections, finding the dosing schedule inconvenient or difficult, not feeling a need for every injection, and having nobody available to help administer the drug. In a US study conducted using a telephone survey at baseline and monthly telephone follow-up calls for 6 months, it was found that injection anxiety at baseline predicted lower levels of adherence at 4 and 6 months.12 Needle phobia, which affects up to 22% of the general population, can also be a significant barrier to adherence to self-administered therapies among MS patients.32 33 Mohr et al.34 noted that 18% of 101 patients studied experienced high levels of injection anxiety. Managing psychosocial concerns that may arise during treatment such as injection anxiety, stress, cognitive dysfunction, or economic issues may enhance patient adherence to therapy.11 Support and education offered by health-care personnel such as nurses, physician assistants, or neurologists may alleviate some of these concerns. Continued advice and appropriate recognition of factors resulting in nonadherence can be vital in keeping patients on therapy and hence sustaining the beneficial effects of DMTs over the long term. Several well-developed training programs to help patients self-inject have been shown to help alleviate some of the convenience-related problems associated with injectable therapies.35–37

The second most common reason for nonadherence in our cohort (25.9%) was perceived lack of efficacy of the DMTs. This finding is consistent with other results published in the international literature. Tremlett and Oger29 concluded that perceived lack of efficacy was the single most common reason for interrupted interferon therapy, cited by 30% of patients. Similar figures were reported by Cunningham et al.30 (39%) and Portaccio et al.28 (29%). Setting appropriate expectations at the initiation of therapy in the context of an effective patient-provider relationship is a key factor in increasing adherence. Although all first-line DMTs have proven efficacy in reducing relapse rates and delaying disease progression, many patients are expecting their disease to be cured. Symptoms such as intermittent paresthesia, urinary urgency and incontinence, fatigue, and other paroxysmal phenomena such as trigeminal neuralgia or Lhermitte sign may be interpreted by the patient as a relapse or ongoing disease progression. Educating patients on the natural history of MS, helping them to differentiate pseudo-exacerbations from true relapses, and earlier institution of symptomatic therapy may help moderate patient expectations of therapy and improve their ability to cope with the disease.11

A total of 23.5% of patients stopped therapy because of adverse events. The most common side effects were injection-site reaction, headache, and flu-like symptoms. The rate of adverse events was consistent with the reported range of 14% to 52%.9 38 39 Most adverse events tend to diminish in frequency and severity with increased time on treatment.40 41 Educating the patient on appropriate injection techniques, the availability of new injection devices, the use of escalating dosages, and concomitant administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can minimize these adverse events and thus increase adherence.32 42–47

Physician-documented disease progression was another factor in nonadherence in our study, with 17.7% of nonadherent patients discontinuing their DMTs upon being told that the disease had entered a progressive phase and the likelihood of ongoing beneficial effects was low. This rate is lower than other published data, but the number of SPMS patients included in our analysis was small. Daugherty et al.38 found that 40% of patients had stopped their DMTs because of disease progression. However, their study relied on patient reports rather than empirical evidence of disease progression, as the study was based on a telephone survey of 108 patients. Several articles reported that high EDSS score influenced adherence rate, as discussed above.8 9 29 30 Cunningham et al.30 found that 32% of patients had EDSS scores of 6 to 9.5 at therapy initiation, which may partly explain the high proportion of patients stopping therapy in their cohort. Physicians were more often involved in decisions to initiate or escalate therapy than to stop therapy. Most neurologists do not instruct patients to discontinue their DMTs when a secondary progressive stage of the disease is diagnosed, since there are no alternative therapies at this stage. In our study, a few neurologists elected to continue IFNβ-1b SC in patients taking that medication, as there were some data supporting delay in disease progression over the long term.

In summary, this study found a relatively high rate of nonadherence to first-line DMTs among MS patients in Kuwait. Among the factors associated with a higher rate of nonadherence were relapsing-remitting course, short disease duration, low number of relapses, and low EDSS score. The most common reasons for discontinuation of DMTs as reported by the patients were inconvenience and perceived lack of efficacy of the DMT.

This study has several limitations. First, the study was retrospective and cross-sectional in nature, reducing the influential power of the outcomes and results. Second, multivariate analysis could not be performed because the registry was recently created and correlation between duration of the disease and other clinical data could not be readily performed. On the other hand, the study has an appropriate sample size and a plethora of data on patients' demographic and clinical data. Because the MS center at Amiri Hospital was only recently established, referral bias could play a role, as most patients who were referred to the clinic had recent diagnoses and thus younger ages and lower EDSS scores.

To our knowledge, this study represents the first examination of reasons for nonadherence to DMTs in patients with MS in the Middle East. The relatively high rate of nonadherence found in Kuwait requires further investigation, especially given the nonadherent patients' relatively young age and low overall disease-related disability. Factors predisposing patients to discontinue their DMTs should be identified early and discussed openly. Patient expectations concerning treatment and its influence on the disease course are a factor in adherence to long-term therapy. Health-care providers must recognize the pivotal role they play in influencing adherence through education and advocacy. Although suboptimal adherence to MS therapies remains a problem and may affect long-term disease progression, various strategies such as the development of new injection devices, educating patients on appropriate measures to alleviate or decrease adverse events, and the recent development of oral therapies may make these treatments more acceptable to patients.

PracticePoints

Nonadherence to first-line disease-modifying therapy in patients diagnosed with MS is a problem in Kuwait and may contribute to disease relapses.

Exploring the reasons for nonadherence early may improve compliance and management of disease progression over the long term.

Management of MS requires a multidisciplinary approach and effective communication between the patient and health-care professionals.

References

Cohen BA. Adherence to disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2006;(suppl):32–37.

Costello K, Kennedy P, Scanzillo J. Recognizing non-adherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. Medscape J Med. 2008; 10:225.

Petrak F, Stridde E, Leverkus F, Crispin AA, Forst T, Pfützner A. Development and validation of a new measure to evaluate psychological resistance to insulin treatment. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30: 2199–2204.

Cohen C, Hellinger J, Johnson M, et al. Patient acceptance of self-injected enfuvirtide at 8 and 24 weeks. HIV Clin Trials. 2003; 4: 347–357.

Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, et al. Therapeutic expectations of patients with multiple sclerosis upon initiating interferon beta-1b: relationship to adherence to treatment. Mult Scler. 1996; 2: 222–226.

Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Likosky W, Levine E, Goodkin DE. Injectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self-inject. Ann Behav Med. 2001; 23: 125–132.

Berger BA, Hudmon KS, Liang H. Predicting treatment discontinuation among patients with multiple sclerosis: application of the transtheoretical model of change. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004; 44: 445–454.

Río J, Porcel J, Téllez N, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 306–309.

Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R, et al. The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2011; 18: 69–77.

Fraser C, Hadjimichael O, Vollmer T. Predictors of adherence to glat-iramer acetate therapy in individuals with self-reported progressive forms of multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2003; 35: 163–170.

Brandes DW, Callender T, Lathi E, O'Leary S. A review of disease-modifying therapies for MS: maximizing adherence and minimizing adverse events. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009; 25: 77–92.

Turner AP, Williams RM, Sloan AP, Haselkorn JK. Injection anxiety remains a long-term barrier to medication adherence in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2009; 54: 116–121.

Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Allen J, et al. Depression and multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1996; 46: 628–632.

Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, Gatto N, Baumann KA, Rudick RA. Treatment of depression improves adherence to interferon beta-1b therapy for multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1997; 54: 531–533.

Sabate E, ed. Adherence to Long-Term Therapeutics: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

Shah N, Behbahani J, Shah M. Prevalence and correlate of major chronic illnesses among Kuwaiti nationals in two governorates. Med Princ Pract. 2010; 19: 105–112.

Sabri S, Bener A, Eapen V, Abu Zeid MS, Al-Mazrouei AM, Singh J. Some risk factors for hypertension in the United Arab Emirates. East Mediterr Health J. 2004; 10: 610–619.

Serour M, Alqhenaei H, Al-Saqabi S, Mustafa A, Ben-Nakhi A. Cultural factors and patients' adherence to lifestyle measures. Br J Gen Pract. 2007; 57: 291–295.

IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, part I: clinical results of a multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1993; 43: 655–661.

Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996; 39: 285–294.

PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and Disability by Interferon-1a Subcutaneously in Multiple Sclerosis) Study Group. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon-1a in relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998; 352: 1498–1504.

Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, et al. Extended use of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) is well tolerated and maintains its clinical effect on multiple sclerosis relapse rate and degree of disability. Neurology. 1998; 50: 701–708.

Jacobs LD, Beck RW, Simon JH, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343: 898–904.

Comi G, Filippi M, Barkhof F, et al. Effect of early interferon treatment on conversion to definite multiple sclerosis: a randomised study. Lancet. 2001; 357: 1576–1582.

Kappos L, Polman CH, Freedman MS, et al. Treatment with interferon beta-1b delays conversion to clinically definite and McDonald MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. Neurology. 2006; 67: 1242–1249.

Comi G, Martinelli V, Rodegher M, et al. Effect of glatiramer acetate on conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (PreCISe study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009; 374: 1503–1511.

European Study Group on interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MS. Placebo-controlled multicentre randomised trial of interferon beta-1b in treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998; 352: 1491–1497.

Portaccio E, Zipoli V, Siracusa G, Sorbi S, Amato MP. Long-term adherence to interferon beta therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2008; 59: 131–135.

Tremlett HL, Oger J. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the b-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology. 2003; 61: 551–554.

Cunningham A, Gottberg K, von Koch L, Hillert J. Non-adherence to interferon-beta therapy in Swedish patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010:121:154–160.

Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A, et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol. 2009; 256: 568–576.

Patti F. Optimizing the benefit of multiple sclerosis therapy: the importance of treatment adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010; 4: 1–9.

Cox D, Stone J. Managing self-injection difficulties in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006; 38: 167–171.

Mohr D, Likosky W, Levine E, Goodkin D. Injectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self inject. Ann Behav Med. 2001; 23: 125–132.

Portaccio E, Amato M. Improving compliance with interferon-beta therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2009; 23: 453–462.

Girouard N, Théorêt G. Management strategies for improving the tolerability of interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2008; 30: 18–25.

Denis L, Namey M, Costello K, et al. Long-term treatment optimization in individuals with multiple sclerosis using disease-modifying therapies: a nursing approach. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004; 36: 10–22.

Daugherty K, Butler J, Mattingly M, Ryan M. Factors leading patients to discontinue multiple sclerosis therapies. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2005; 45: 371–375.

Gottberg K, Gardulf A, Fredrikson S. Interferon-beta treatment for patients with multiple sclerosis: the patients' perceptions of the side effects. Mult Scler. 2000; 6: 349–354.

Kappos L, Traboulsee A, Constantinescu C, et al. Long-term subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Neurology. 2006; 67: 944–953.

PRISMS Study Group, University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group. PRISMS-4: long-term efficacy of interferon-beta-1a in relapsing MS. Neurology. 2001; 56: 1628–1636.

Mikol D, Lopez-Bresnahan M, Taraskiewicz S, Chang P, Rangnow J. A randomized, multicentre, open-label, parallel-group trial of the tolerability of interferon beta-1a (Rebif) administered by autoinjection or manual injection in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 585–591.

Bayas A, Rieckmann P. Managing the adverse effects of interferon beta therapy in multiple sclerosis. Drug Saf. 2000; 22: 149–159.

Giovannoni G, Barbarash O, Casset-Semanaz F, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a new formulation of interferon beta-1a (Rebif New Formulation) in a Phase IIIb study in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: 96-week results. Mult Scler. 2009; 15: 219–228.

Jaber A, Bozzato GB, Vedrine L, Prais WA, Berube J, Laurent PE. A novel needle for subcutaneous injection of interferon beta-1a: effect on pain in volunteers and satisfaction in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2008; 8:38.

Cramer JA, Cuffel BJ, Divan V, Al-Sabbagh A, Glassman M. Patient satisfaction with an injection device for multiple sclerosis treatment. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006; 113: 156–162.

Yamout BI, Dahdaleh M, Al Jumah MA, et al. Adherence to disease-modifying drugs in patients with multiple sclerosis: a consensus statement from the Middle East MS Advisory Group. Int J Neurosci. 2010; 120: 273–279.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.