Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Target Coping Strategies for Interventions Aimed at Maximizing Psychosocial Adjustment in People with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Background:

The experience of psychological distress is prevalent in people with multiple sclerosis (MS), including high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. It has been shown that people with MS use less adaptive coping compared with healthy individuals. This study examined the ability of coping strategies to predict maladaptive and adaptive psychosocial outcomes across areas of stress, depression, anxiety, and quality of life (QOL) in people with MS.

Methods:

107 people with MS completed measures of depression (Beck Depression Inventory–II), anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory), QOL (Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life–54), stress (Daily Hassles Scale), and coping (COPE inventory).

Results:

Consistent with expectations, depression, frequency of stress, trait anxiety, and mental health QOL were predicted by adaptive and maladaptive coping styles. Severity of stressful events was predicted by maladaptive, but not adaptive, coping styles. Depression and mental health QOL were most prominently connected to coping use. Emotional preoccupation and venting showed the strongest relationship with poorer psychosocial outcomes, whereas positive reinterpretation and growth seemed to be most beneficial.

Conclusions:

The results of this study highlight the importance of intervention programs targeting specific coping strategies to enhance psychosocial adjustment for people with MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a variable and unpredictable chronic inflammatory disease affecting the central nervous system. Common symptoms include fatigue, pain, physical disability, muscular weakness and spasms, sensory changes, cognitive dysfunction, and depression.1 Multiple sclerosis, the most common neurodegenerative condition affecting young adults (typical age at onset, 20–40 years), has the potential to cause significant life disruption, including changes in work life and personal and social relationships.2 Emotional disturbances, including depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorders, are frequent in people with MS.3 Compared with a 15.0% lifetime prevalence of depression in the general Australian population,4 up to 50% of people with MS experience depression after disease onset.1 Similarly, anxiety is prevalent, with 15% to 54% of people with MS experiencing clinically significant anxiety symptoms.5

Adaptive coping is beneficial for people with MS not only because of the relationship of coping strategies with psychosocial adjustment to disease but also because of the probable relationship between stress and disease progression.6 The process of coping can be defined as the range of thoughts and behaviors used to manage stressful internal and external demands, and it is initiated when the person feels that important goals have been threatened, harmed, or lost.7 Coping strategies are often conceptualized as problem-focused or emotion-focused. Problem-focused strategies are generally considered adaptive and aimed at changing the stressor, and emotion-focused strategies are often considered maladaptive and aimed at managing the stressor through emotions.7 This two-pronged model has been criticized for not adequately capturing the range of commonly used strategies.8 Although other models have been proposed to include avoidance-, social-, or meaning-oriented categories,7 this two-pronged approach is still used in the current literature.9–11

Lazarus and Folkman12 proposed that emotion-focused coping strategies are used more by people in situations they feel powerless to change, such as when faced with chronic illness. People with MS have been shown to use less-adaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance and wishful thinking, over positive and problem-focused strategies, and this is related to higher levels of psychological distress and depression and lower quality of life (QOL).13 14

Much of the research addressing coping in people with MS has used the Ways of Coping inventory,15 which assesses a limited range of coping strategies and combines some strategies so that the impact of specific coping strategies may not be identified. For example, it does not assess acceptance or humor, and it adds a religious element into the positive reinterpretation strategy. In addition, the Ways of Coping inventory combines planning and problem-solving. Research in people with MS using the COPE inventory8 has linked planning with higher anxiety,16 higher depression in early-diagnosed people with MS (<4 years),17 and higher perceived stress and psychological distress in wartime.18 It seems plausible that planning is not adaptive for people with MS in some circumstances. This may not have been identified with the Ways of Coping inventory, because the stress-enhancing effect of planning may be canceled out by a stress-buffering effect of problem-solving on the outcome variable.19 Greater understanding of this and other coping relationships linked with better or poorer psychosocial adjustment outcomes for people with MS is critical given that coping is amenable to interventions that enhance adaptive coping skills and decrease maladaptive coping.7 We sought to identify a relationship with coping strategies that are beneficial or problematic to psychosocial adjustment outcomes to guide the development of interventions aimed at increasing QOL for people with MS.

Methods

Sample

As described previously,20 21 people with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) or secondary progressive MS (SPMS) subtypes were recruited through two hospital MS clinics in Melbourne, Australia, and via online advertisements through MS Australia. Participants were aged 18 years or older and were diagnosed as having MS per current McDonald criteria.22 Competence to provide informed consent was established by a Mini-Mental State Examination23 score of 25 or greater. Subtypes other than RRMS or SPMS were excluded from the research, as were participants with comorbid neurologic damage, severe psychological disorder not in remission other than anxiety or depression, or a history of severe drug or alcohol abuse. Participants were MS relapse free for 3 months before their research appointment and were free of corticosteroid medication for 60 days. Ethical approval was granted through the Department of Health, Victoria, Multi-Site Streamline Ethical Review System, as assessed by Monash Health, Melbourne.

Measures

Independent Variable

Coping. Coping was assessed using the 60-item COPE inventory,8 which measures a comprehensive range of adaptive and maladaptive coping styles and has been used previously in MS research.16 24 Participants were asked to answer how they would cope in situations when they are under a lot of stress to identify their dispositional coping style. Each strategy is derived from four items. Strategies include active, planning, suppression of competing activities (suppression), restraint, seeking instrumental social support (instrumental social support), positive reinterpretation and growth (growth), acceptance, turning to religion (religion), seeking emotional social support (emotional social support), focus on and venting of emotions (venting), denial, behavioral disengagement, mental disengagement, and substance abuse. In addition, total coping, a calculated sum of inventory endorsements, and an adaptive coping index were calculated. The adaptive coping index was derived using the method reported by Rabinowitz and Arnett,25 which used the sum of z scores for three adaptive coping strategies (active coping, planning, and suppression) minus the sum of z scores for three maladaptive strategies (mental disengagement, behavioral disengagement, and denial). See Table S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org, for a description of each coping strategy.

Outcome Variables

Depression. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)–II26 was used to assess depression symptoms. It is a 21-item scale with responses ranging from 0 (absence of symptoms) to 3 (severe symptoms).

Anxiety. Anxiety was measured using the trait scale from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory,27 a 20-item scale about the person's day-to-day disposition to anxiety. Items are endorsed on a Likert scale from 1 to 4, with subscale scores ranging from 20 to 80.

Stress. Stress frequency and severity were measured using the Daily Hassles Scale.28 This 117-item scale measures a broad range of potential daily stressors and provides a frequency and severity of stress scale.

Quality of Life. The QOL was measured using the physical health and mental health composite indices from the MS Quality of Life–54 (MSQOL-54).29 This 54-item scale derives the mental health and physical health indices from a series of weighted subscales, calculated to provide the participant with a score out of 100.

Control Variables

Vision Screen. The Rosenbaum Pocket Vision Screener, a pocket-sized card that assesses visual acuity of 20/20 to 20/800 from 14 inches, was used to assess and control for visual acuity deficits that may affect psychosocial adjustment outcomes.

Sociodemographic Data. Sociodemographic information was collected via a semistructured screening interview to control for the relationship between these variables and psychosocial adjustment in analysis. Information collected included age, sex, years of education, disease duration (time since symptom onset and time since diagnosis), subtype, and use of mood-altering medications (antidepressants and benzodiazepines). The participant's treating neurologist provided Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores (where available), confirmation of diagnosis, and subtype using a standard form and a prepaid reply envelope.

Procedure

The COPE inventory, Daily Hassles Scale, and MSQOL-54 were mailed to participants a week before a scheduled appointment. After the provision of informed consent, including Mini-Mental State Examination administration, participants were administered the Rosenbaum Pocket Vision Screener, the Beck Depression Inventory–II, and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. If the COPE inventory, Daily Hassles Scale, and MSQOL-54 had not been completed, participants were provided with time to complete these.

Analysis

Before analysis, variables that were not normally distributed were transformed using log or square root transformations. Variables that did not respond to transformations were grouped into high and low responses to enable binary analysis. This included six of 17 coping variables: behavioral disengagement, denial, humor, planning, religion, and substance abuse; and two of six outcome variables: trait anxiety and stress severity. Hierarchical linear regression was used to analyze continuous outcome measures, whereas hierarchical logistic regression was used for binary outcome measures. Power analysis was performed using G*Power software for multiple regression.30 Analysis to find a medium effect, with power of 0.8 and the P value set at .05 or less, using the current sample size (N = 107), specified use of up to seven independent variables in the regression analysis.

For all the analyses, demographic and disease-related variables that were significantly correlated at P ≤ .05 with the outcome variable of interest were covaried by placing them in the first step of the regression model to control for their effects. This included antidepressant use for depression; vision, subtype, time since diagnosis, antidepressant and benzodiazepine use for trait anxiety; vision, subtype, antidepressant and benzodiazepine use for stress frequency; benzodiazepine use for stress severity; age, vision, EDSS score, subtype, and antidepressant use for physical health QOL; and antidepressant and benzodiazepine use for mental health QOL. See Table S2 for the correlation table. At step 2 of the regression modeling process, each coping variable that was significantly correlated with the outcome variable was individually entered into the regression model. A final model was developed using the coping variables that were individually significant predictors of the outcome variable, with the aim of identifying the most useful predictive model. The exception was for the adaptive coping index and total coping index, which were not added to the final model of analysis when significant because they were derived from combined coping strategies, which would risk artificially inflating the model outcome. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).31

Results

Study Participants

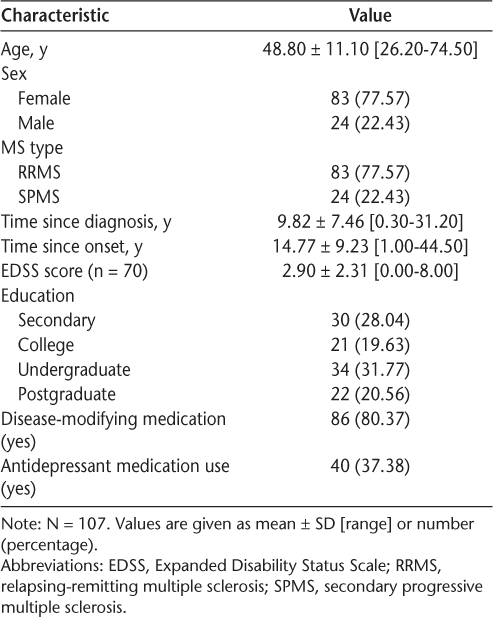

Demographic information is provided in Table 1. Data analysis was performed for 107 people with MS. Most participants had RRMS, and there were more women than men, consistent with MS subtype and sex distribution. The EDSS scores,32 provided by participants' treating neurologists, were available for 70 participants. Analysis of participants with and without EDSS scores found no significant between-group differences for sex, subtype, age, time since onset, time since diagnosis, education, disease-modifying medication, or taking antidepressant or benzodiazepine medications (all P > .05) (data not shown).

Participant demographic and disease-related data

Outcome Measures

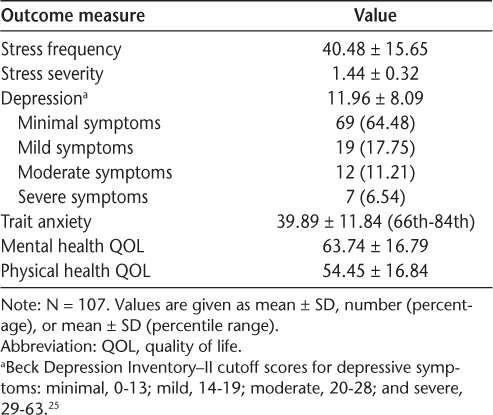

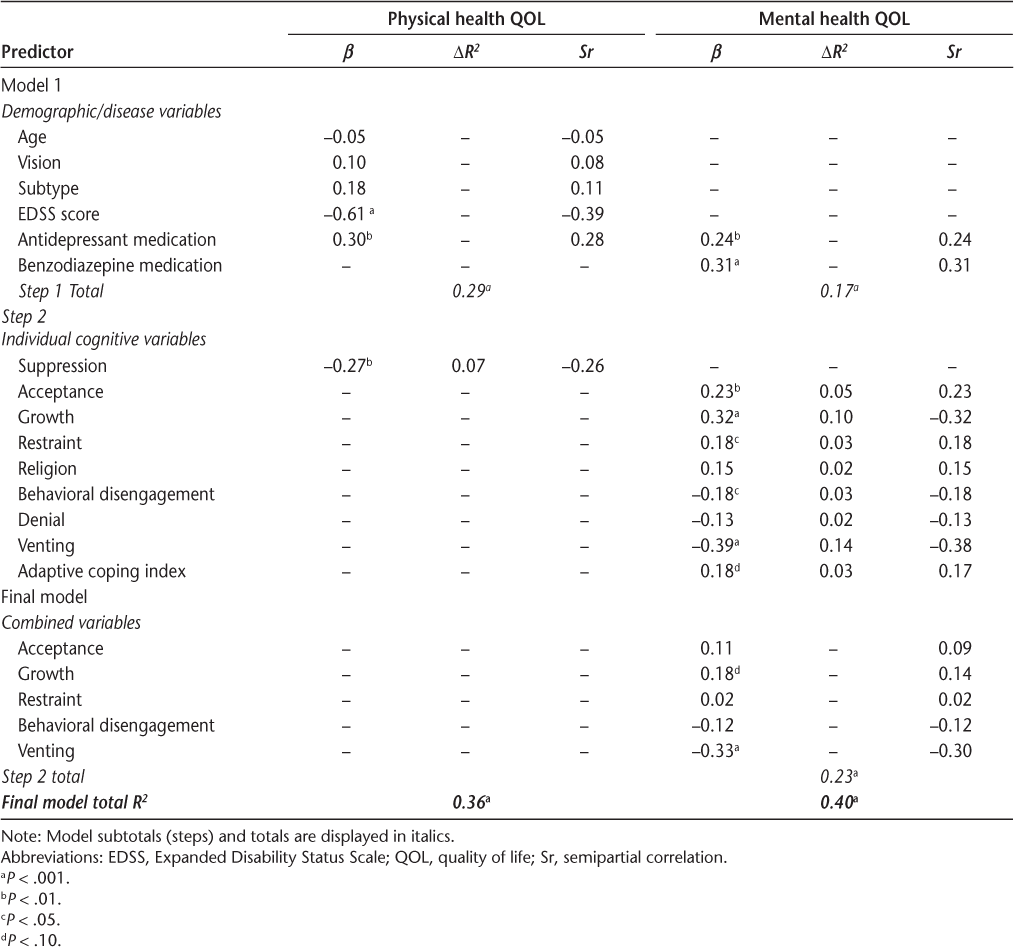

Descriptive data for the outcome measures of stress, depression, anxiety, and QOL are displayed in Table 2, and results of regression analyses are displayed in Tables 3 through 5. Correlations among these psychosocial variables are provided in Table S2.

Descriptive data for psychosocial adjustment outcome measures

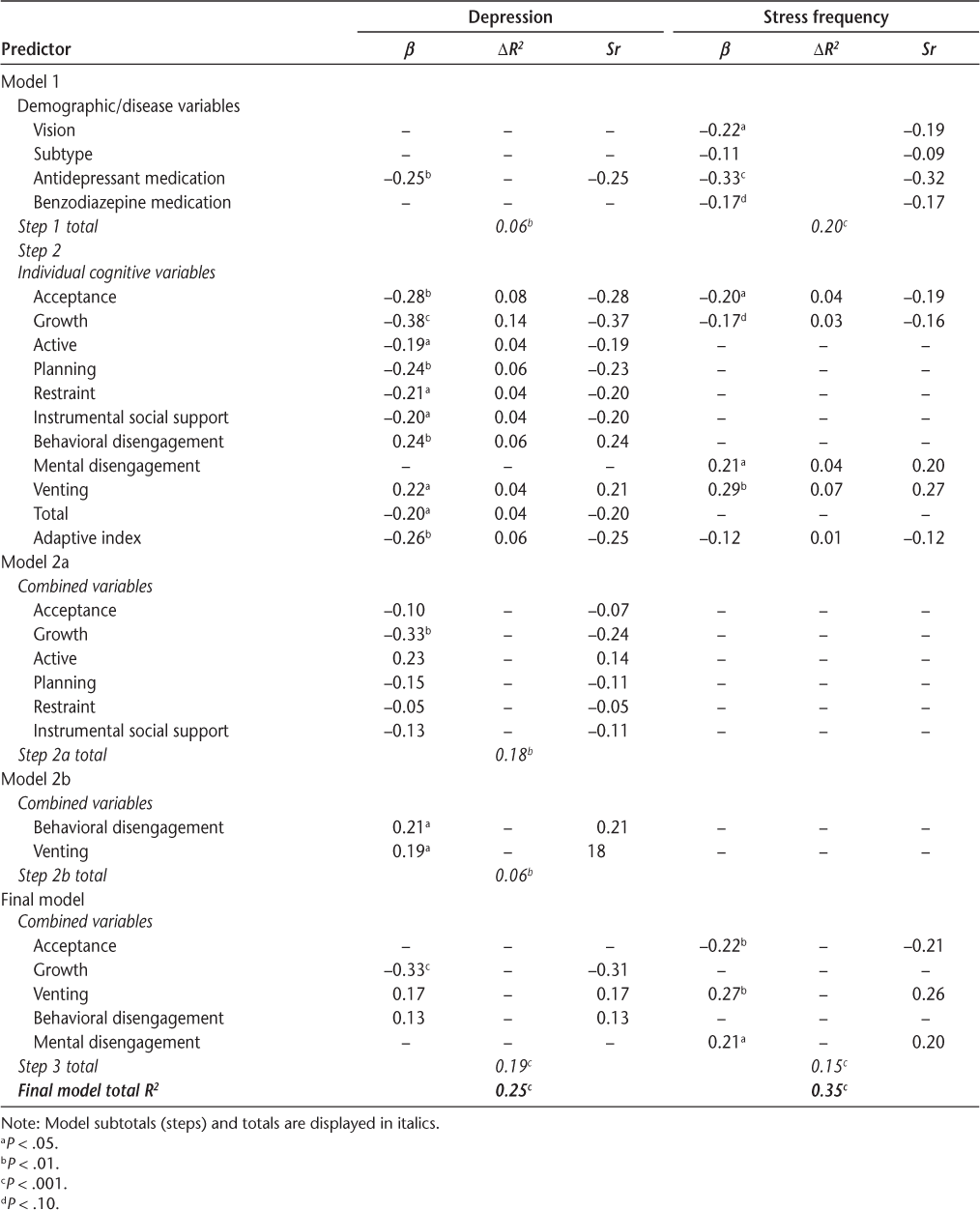

Hierarchical regression analysis of significantly correlated coping variables for the outcome variables depression and stress frequency

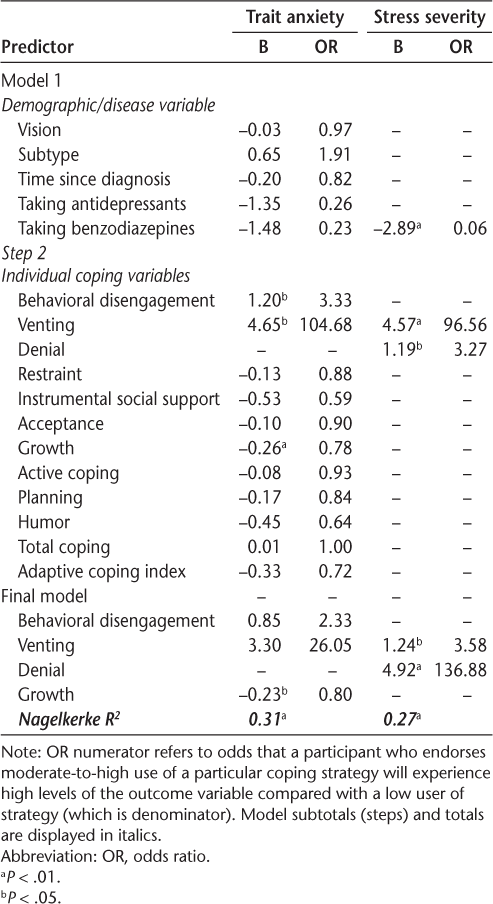

Regression analysis of significantly correlated coping strategies for the outcome variables trait anxiety and stress severity

Hierarchical regression analysis of significantly correlated coping variables for the outcome variables physical health and mental health QOL

Depression

Nine of the COPE inventory strategies, total coping, and the adaptive coping index were significantly correlated with depression. When entered into the regression model individually, each of these strategies significantly predicted 3.5% (active) to 13.8% (growth) of the variability in depressive symptoms. Higher use of acceptance, growth, active, planning, restraint, instrumental social support strategies, total coping, and the adaptive coping index predicted lower depressive symptoms, whereas behavioral disengagement and venting predicted higher depressive symptoms.

To comply with power analysis calculations limiting regression analysis to a maximum of seven independent variables, combined coping variable analysis was divided into two models. In model 2a, the adaptive coping variables were jointly entered at step 2, and joint analysis of maladaptive coping variables was performed in model 2b. Total coping and the adaptive coping index were not included in the combined analysis. When the six adaptive coping variables were entered into step 2 of model 2a, the step significantly predicted 17.3% of the variability in depressive symptoms, although only growth coping was a significant contributor, uniquely predicting 5.7% of the variability. When the two maladaptive coping variables were jointly entered into step 2 of model 2b, they both remained significant, and the step accounted for 6.3% of the variability. Growth, venting, and behavioral disengagement were jointly entered into step 2 of the final model, and the step significantly predicted 18.6% of the variability in depressive symptoms. Growth coping was the only significant predictor and uniquely accounted for 9.7% of the variability, although venting was approaching significance. The overall model predicted 24.9% of the variability in depressive symptoms.

Stress/Hassles

Stress Frequency. Four coping variables and the adaptive coping index were significantly correlated with stress frequency and were individually entered into the regression analysis. Three of these variables—acceptance, mental disengagement, and venting—significantly predicted stress frequency and uniquely accounted for 3.7%, 4.1%, and 7.3% of the variability, respectively. Higher use of acceptance coping predicted lower frequency of stress, whereas higher use of mental disengagement or venting predicted higher stress frequency. When these variables were jointly entered into step 2 of the final model, they each remained significant, with the step predicting 15.0%, and the overall model predicting 35.0%, of the variability in stress frequency.

Stress Severity. Denial and venting coping were significantly correlated with stress severity, and, when entered individually at step 2, they both significantly predicted stress severity. Participants who endorsed high denial coping were 3.2 times more likely to endorse high stress severity, and participants who endorsed high venting coping were 96.7 times more likely to endorse high severity of stress. When denial and venting were jointly entered into step 2 of the final model, they both remained significant. The model significantly predicted 27.0% of the variability in severity of stress.

Trait Anxiety

Nine individual coping strategies, total coping, and the adaptive coping index were correlated with trait anxiety and were individually entered into step 2. Three of these variables—behavioral disengagement, venting, and growth—significantly predicted trait anxiety and were jointly entered into the final model. Given that there were five disease/demographic variables entered at step 1 of the model, to comply with power analysis requirements of up to seven variables, time since diagnosis, which contributed least to the model of all demographic variables, was removed before running the final model. When entered into step 2, the model significantly predicted 30.6% of the variability in trait anxiety, although growth coping was the only variable to reach significance. Participants who endorsed higher use of growth coping were 1.25 times less likely to endorse high trait anxiety.

Quality of Life

Mental Health QOL Composite. Seven coping variables and the adaptive coping index were significantly correlated with mental health QOL and were individually entered into step 2 of the analysis. Five of these variables significantly predicted 3.2% (restraint and behavioral disengagement) to 14.2% (venting) of the variability. Higher use of acceptance, growth, and restraint coping predicted higher mental health QOL, whereas higher use of behavioral disengagement or venting predicted lower mental health QOL. When these variables were jointly entered into step 2 of the final model, the step significantly predicted 22.5% of the variability in mental health QOL, although only venting reached significance, uniquely predicting 9.2% of the variability. The overall model accounted for 39.2% of the variability.

Physical Health QOL Composite. Given that EDSS score was obtained for only 70 participants, regression analysis was conducted with and without this variable. Only the analysis with EDSS score is reported herein, although the results of the analysis without EDSS score, which included all 107 participants, is provided in Appendix S1.

Only suppression coping correlated with physical health QOL, and lower use of suppression coping significantly predicted higher physical health QOL, accounting for 6.7% of the variability. The entire model accounted for 35.7% of the variability in physical health QOL.

Discussion

Consistent with expectations, maladaptive coping styles predicted higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety and lower QOL, and adaptive coping styles predicted lower levels of stress frequency, depression, and trait anxiety and higher QOL. Severity of stressful events was predicted by maladaptive, but not adaptive, coping styles.

Of the psychological adjustment measures used in this study, depressive symptoms were most often predicted by coping styles, with acceptance, growth, active, planning, restraint, and instrumental social support coping individually predictive of lower levels of depressive symptoms, and behavioral disengagement and venting predicting higher depressive symptoms. However, when these strategies were analyzed in combination, only growth coping remained significant and uniquely contributed to 9.7% of the variance. Growth also significantly predicted lower trait anxiety in the final model of this analysis, as well as being an individual predictor of better mental health QOL. Consistent with this, growth coping has been related to lower depression in previous cross-sectional and longitudinal research with people with MS.16 33 Growth and acceptance are intimately linked. As psychologist Carl Rogers famously wrote about personal growth attributed to acceptance, “…the curious paradox is that when I accept myself as I am, then I change.”34 Growth and acceptance have been shown to be beneficial for psychosocial adjustment for people experiencing chronic illness generally,7 and acceptance has been shown to be an important component in the process of adaptation to chronic illness for people with MS.35 In the current research, acceptance was a significant predictor in the final stress frequency model, where it predicted lower frequency of stress and uniquely contributed 4.4% of the variability. It also predicted lower depressive symptoms and higher mental health QOL, although it was not significant in the final models due to its moderate correlation with growth (r = 0.54). In previous research, acceptance has been related to reduced depressive symptoms, including longitudinally, and higher mental health QOL.25 36 37 The ability to accept one's personal situation enables the person to focus resources on attaining future ambitions and goals.38 Thus, people with MS would benefit from psychological therapies and interventions aimed at enhancing disease acceptance and identifying personal growth gains they may have attained, particularly because both of these strategies are adaptive and are considered emotion-focused coping strategies, which are more often used by people when a situation cannot be changed.12

The results of this study point to the use of venting coping as the most damaging strategy to psychological adjustment for people with MS. This strategy was a significant predictor in the final models for stress frequency and severity, where it uniquely contributed to 6.8% of variability in stress frequency and a very high probability that moderate-to-high users of venting endorsed higher levels of stress severity. It was a significant predictor in the final model for mental health QOL, such that higher users of venting coping endorsed lower levels of mental health QOL, uniquely accounting for 9.0% of the variability. Although not significant in the final model for depression and trait anxiety, when individually analyzed, higher venting significantly predicted higher depression and trait anxiety.

Venting and a preoccupation with emotions have been related to higher levels of depressive symptoms in people with MS,39 including those who have been newly diagnosed (<4 years),17 and have been related to higher levels of anxiety symptoms.39 Similarly, venting has been related to higher depression and anxiety in other patient groups, patients' spouses, elderly individuals, and health care workers.40–43 These findings are in contrast to catharsis theory, which suggests that venting of distress is psychologically beneficial, although it has been proposed that it is only beneficial if the person engages in cognitive processing of the issues.44 It is possible that the use of venting as a coping strategy does not incorporate focused processing required for cathartic benefits. A study that assessed venting of anger showed it to be linked to maintenance of anger and aggression levels compared with a distraction and control condition, which the author proposed to be linked to associated rumination.45 These findings are consistent with the view that preoccupation with emotions has been found to be related to higher levels of psychopathology, particularly depression, and it is thought that this is due to rumination about the stressor, which maintains emotional dysregulation.46 The present research and results of previous studies highlight the need for therapeutic interventions to reduce coping through excessive emotional focus and expression related to stressful events and experiences. Future research aimed at delineating the beneficial and detrimental aspects of catharsis/venting is required.

The COPE inventory measures avoidance coping through three strategies: behavioral and mental disengagement and denial coping. Higher use of denial coping significantly predicted higher stress severity, consistent with previous research by Somer et al.,18 who found that denial coping was related to higher perceived stress and psychological distress, whereas higher mental disengagement predicted higher frequency of stressful events. When individually analyzed (without other coping strategies), endorsement of behavioral disengagement significantly predicted depressive symptoms, trait anxiety, and mental health QOL but was not significantly predictive of psychosocial adjustment outcomes when combined in any of the final models. Previous research has shown behavioral disengagement to predict anxiety16 and both behavioral disengagement and mental disengagement to correlate with depressive symptoms in people with MS diagnosed for less than 4 years.17 25 More generally, avoidance coping has been related to depression and anxiety in several studies, including longitudinally.14 33 37 Avoidance coping may be considered adaptive for short-term medical issues, such as use of cognitive avoidance when requiring an injection. However, use of this strategy for people with more serious and longer-term health problems has been associated with negative outcomes,47 as has been shown to be the case for people with MS, making it a target for modification.

Use of planning coping predicted only one adjustment outcome, depression, and contrary to expectations from previous research, it predicted lower depressive symptoms, suggesting that for people with MS it is adaptive for psychosocial adjustment. Planning has been linked to higher depression in people with MS in the early diagnosis phase (<4 years),17 and this may have contributed to its maladaptive status given that uncertainty and disruption characterize the earliest stages of adjustment to chronic illness, making planning difficult.48 Another study that showed planning was related to higher perceived stress and psychological distress was conducted under the duress of war conditions,18 which, again, may be situation specific. However, a relationship of planning coping with increased anxiety was shown in a more heterogeneous sample of people with MS, although it may have some bias because participants were all recruited from an MS symposium.16 Thus, these results suggest the adaptive relationship between planning coping and adjustment found in the present study remains tentative because the adaptive nature of planning seems to have some limitations. Problem-solving coping has long been linked to adaptive outcomes but has been considered less useful in chronic illness, where the stressor cannot be changed.12

Whereas problem-solving strategies were generally not significant in the final model of the psychosocial adjustment outcomes, when individually analyzed, restraint, active, and the adaptive coping index predicted lower depressive symptoms, and restraint also predicted higher mental health QOL. Similarly, active coping has predicted lower depression in people with MS in previous research,33 suggesting that people with MS benefit from the use of these problem-solving strategies in areas of their life that are changeable, and this should be encouraged. An interesting and unexpected finding was the negative relationship between physical health QOL and suppression coping (also considered a problem-solving strategy) because this strategy is generally considered to be an adaptive coping style.26 Given that suppression requires a person to focus on only the issue at hand, the finding that suppression predicted lower physical health QOL in this study may reflect a practical coping strategy that is adopted out of necessity by some people with MS who have a higher level of physical impairment.

It is noteworthy that, in the present study, coping strategies that showed the greatest relationship with psychosocial adjustment were those that might be considered emotion-focused under the two-pronged emotion-focused and problem-focused theory of coping.12 Importantly, these strategies are related to adaptive (eg, growth) and maladaptive (eg, venting) adjustment outcomes, underscoring the misconception of emotion-focused coping as primarily maladaptive and endorsing the need to consider coping strategies in terms of theoretical perspectives that have broadened categories of coping to include avoidant-, social-, and meaning-oriented coping7 in research focused on people with MS, and potentially chronic illness research more generally.

This study has some limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the present study precludes making causal inferences for the relationships examined. Although it is hypothesized that coping predicts adjustment, which has been tested in this research, it is equally plausible that adjustment may predetermine a person's coping strategy choice. No alpha-level adjustment has been applied to statistical analysis to protect against familywise error because of the potential risk of raising type II error and the controversy surrounding the appropriateness of using correction techniques.49 In addition, the self-selection method of recruitment may mean that the current sample is not representative of all people with RRMS or SPMS. Results should be interpreted with these limitations in mind.

In conclusion, the findings of this research show a link between coping strategies and psychosocial adjustment in people with MS. In particular, emotional preoccupation and venting and avoidance strategies, including denial and mental and behavioral disengagement, have been linked to poorer psychosocial adjustment outcomes and are targets for modification. Acceptance and, particularly, growth coping showed a strong relationship with better adjustment. In terms of the relationship between coping strategies and psychological adjustment outcomes measured, depression and mental health QOL seem to be the most strongly related to both adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies. Given that depression is prevalent in people with MS and interferes with QOL, the finding that depressive symptoms and mental health QOL are predicted by a variety of coping strategies supports the importance of interventions for people with MS that aim to increase adaptive coping strategies and decrease maladaptive coping strategies, especially given that coping is amenable to change.7

PRACTICE POINTS

Positive reinterpretation and growth and acceptance coping are adaptive strategies that were found to be associated with lower stress, depression, and anxiety and higher quality of life. These coping strategies should be considered targets for interventions to increase use in people with MS.

Focusing on and venting of emotions, as well as avoidance-type coping strategies, are maladaptive strategies that were associated with higher stress, depression, and anxiety and lower quality of life. These coping strategies should be considered for interventions to minimize use in people with MS.

High use of focusing on and venting of emotions coping was a particularly strong predictor of poorer psychosocial adjustment.

Depressive symptoms seem to be strongly interconnected with coping, which highlights the importance of interventions to address difficulties with coping in people with MS.

Financial Disclosures:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Arnett PA, Barwick FH, Beeney JE. Depression in multiple sclerosis: review and theoretical proposal. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14:691–724.

Cohen JA, Rae-Grant A. Handbook of Multiple Sclerosis. 2nd ed. London, UK: Springer Healthcare; 2012.

Minden SL, Feinstein A, Kalb RC, et al. Evidence-based guideline: assessment and management of psychiatric disorders in individuals with MS: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82:174–181.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4326.0. Published 2007. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Boeschoten RE, Braamse AMJ, Beekman ATF, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2017;372:331–341.

Artemiadis A, Anagnostoulis MC, Alexopoulos EC. Stress as a risk factor for multiple sclerosis onset or relapse: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36:109–120.

Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:745–774.

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–283.

Tierney S, Seers K, Reeve J, Tutton L. Appraising the situation: a framework for understanding compassionate care. J Compassionate Health Care. 2017;4:1.

Iova S, Popescu CA, Iova A, Mihanceaa P, Buzoianu AD. Impact of depression on coping strategies in multiple sclerosis patients. Hum Vet Med. 2014;6:165–168.

Schoenmakers EC, Tilburg TG, Fokkema T. Problem-focused and emotion-focused coping options and loneliness: how are they related? Eur J Ageing. 2015;12:153–161.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984.

McCabe MP, Di Battista J. Role of health, relationships, work and coping on adjustment among people with multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal investigation. Psychol Health Med. 2004;9:431–439.

Goretti B, Portaccio E, Zipoli V, et al. Coping strategies, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2009;30:15–20.

Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Ways of Coping Questionnaire: Permissions Set, Manual, Test Booklet, Scoring Key. Sunnyvale, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press Inc; 1988.

Brajkovic L, Bras M, Milunovic V, et al. The connection between coping mechanisms, depression, anxiety and fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Coll Antropol. 2009;33(suppl 2):135–140.

Lode K, Bru E, Klevan G, Myhr KM, Nyland H, Larsen JP. Depressive symptoms and coping in newly diagnosed patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2009;15:638–643.

Somer E, Golan D, Dishon S, Cuzin-Disegni L, Lavi I, Miller A. Patients with multiple sclerosis in a war zone: coping strategies associated with reduced risk for relapse. Mult Scler. 2010;16:463–471.

Aldwin CM, Revenson TA. Does coping help? a reexamination of the relation between coping and mental health. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:337–348.

Grech LB, Kiropoulos LA, Kirby KM, Butler E, Paine M, Hester R. The effect of executive function on stress, depression, anxiety, and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2015;37:549–562.

Grech LB, Kiropoulos LA, Kirby KM, Butler E, Paine M, Hester R. Executive function is an important consideration for coping strategy use in people with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2017;39:817–831.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198.

Aarstad AKH, Lode K, Larsen JP, Bru E, Aarstad HJ. Choice of psychological coping in laryngectomized, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients versus multiple sclerosis patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:907–915.

Rabinowitz AR, Arnett PA. A longitudinal analysis of cognitive dysfunction, coping and depression in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:581–591.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corp; 1996.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. STAI Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Menol Park, CA: Mind Garden; 1983.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Manual for the Hassles and Uplifts Scales: Research Edition. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1989.

Vickrey BG. A health-related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:195–206.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [computer program]. Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2012.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452.

Pozzilli C, Schweikert B, Ecari U, Oentrich W, Bugge J-P. Quality of life and depression in multiple sclerosis patients: longitudinal results of the BetaPlus study. J Neurol. 2012;259:2319–2328.

Rogers CR. On Becoming a Person: A Therapist's View of Psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co; 1961.

Pakenham KI, Fleming M. Relations between acceptance of multiple sclerosis and positive and negative adjustments. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1292–1309.

McCartney Chalk H. Mind over matter: cognitive-behavioral determinants of emotional distress in multiple sclerosis patients. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:556–566.

Pakenham KI. Investigation of the coping antecedents to positive outcomes and distress in multiple sclerosis (MS). Psychol Health. 2006;21:633–649.

Maes S, Leventhal H, De Ridder D. Coping with chronic diseases. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, eds. Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Application. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 1996:221–252.

Fournier M, De Ridder D, Bensing J. Optimism and adaption to chronic disease: the role of optimism in relation to self-care options of type 1 diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. Br J Health Psychol. 2002;7:409–432.

Fasse L, Flahault C, Brédart A, Dolbeault S, Sultan S. Describing and understanding depression in spouses of cancer patients in palliative phase. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24:1131–1137.

Verma P, Rastogi R, Sachdeva S, Gandhi R, Kapoor R, Sachdeva S. Psychiatric morbidity in infertility patients in a tertiary care setup. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:1–6.

Orgeta V, Orrell M. Coping styles for anxiety and depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults. Clin Gerontol. 2014;37:406–417.

McPherson S, Hale R, Richardson P, Obholzer A. Stress and coping in accident and emergency senior house officers. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:230–231.

Bohart A. Toward a cognitive theory of catharsis. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1980;17:192–201.

Bushman BJ. Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger, and aggressive responding. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28:724–731.

Summerfeldt LJ, Endler NS. Coping with emotion and psychopathology. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, eds. Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1996:602–639.

Zeidner M, Saklofske D. Adaptive and maladaptive coping. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, eds. Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 1996:505–531.

Morse JM, Johnson JL. Towards a theory of illness: the Illness Constellation Model. In: Morse JM, Johnson JL, eds. The Illness Experience: Dimensions of Suffering. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991:315–342.

O'Keefe DJ. Colloquy: should familywise alpha be adjusted? against familywise alpha adjustment. Hum Commun Res. 2003;29:431–447.