Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Effect of Mindfulness Meditation on Personality and Psychological Well-being in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Background:

Varied evidence shows that mindfulness-oriented meditation improves individuals' mental health, positively influencing practitioners' personality profiles as well. A limited number of studies are beginning to show that this type of meditation may also be a helpful therapeutic option for persons with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Methods:

We evaluated the effects of an 8-week mindfulness-oriented meditation training on the personality profiles, anxiety and depression symptoms, and mindfulness skills of a group of patients with MS. A control group of patients with MS not enrolled in any training was also tested.

Results:

After mindfulness-oriented meditation training, participants in this group (n = 15) showed an increase in character traits reflecting the maturity of the self at the intrapersonal (self-directedness) and interpersonal (cooperativeness) levels. Moreover, increased mindfulness and conscientiousness and decreased trait anxiety were observed in participants after the training.

Conclusions:

These data support the utility for patients with MS of therapeutic interventions based on mindfulness meditation that may lead to enhanced character and self-maturity.

Multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic, inflammatory, demyelinating, and degenerative disease of the central nervous system, is the most common nontraumatic neurologic disease in young adults.1 Multiple sclerosis has major behavioral and emotional sequelae. Cognitive disturbances occur at various degrees in 40% to 65% of patients,2 3 and more than 50% and approximately 30% of patients experience important depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively, at some point during the disease course.4

A relatively new area of investigation in MS research is personality assessment5 6; recent studies report that personality changes, commonly characterized by apathy, irritability, impulsivity, and social inappropriateness, can be observed in 20% to 40% of patients with MS.5 It has been observed that patients with MS may disclose personality profiles different from those of controls. In the contexts of the Big Five Inventory (BFI)7 and the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI),8 9 patients with MS have reported increased neuroticism and harm avoidance and reduced conscientiousness, agreeableness, extraversion, and self-directedness.4 10–13 Personality disturbances in MS may also be associated with poor coping and reduced quality of life.4 The need for early diagnosis and treatment of disordered personality characteristics in patients with MS is, thus, emphasized in the interests of patients' adherence to treatment, prognosis, and quality-of-life improvement.5 6

Given the complexity of the clinical and psychological manifestations of MS, a significant consensus has formed that a multidisciplinary approach to patient treatment is warranted.5 6 In the past few years, the effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapies has been shown in a wide range of clinical conditions (eg, depression, anxiety, and stress disorders),14 15 with promotion of positive changes in practitioners' personality profiles as well.16–19 Recent research is beginning to show that this form of therapy may also be a helpful therapeutic option for persons with neurodegenerative diseases, including MS.20–22

Mindfulness is an attribute of consciousness that can be developed effectively through the practice of mindfulness-oriented meditation and involves being aware of and attentive to what is occurring in the present moment (in terms of thoughts, emotions, and somatosensory experience) with a nonjudgmental attitude of openness and receptivity.14 15 23 A recent review study of such meditation in MS based on results from 183 patients (predominantly with relapsing-remitting MS) from three controlled trials has concluded that mindfulness-based therapies could be beneficial for patients with MS in terms of improvements in quality of life and reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms and in perceived fatigue.22 More recent controlled trials or cross-sectional studies support the use of mindfulness-based therapies as an effective management adjunct for MS.24–28 Despite these encouraging results, the mechanisms of change that moderate the psychological benefits of mindfulness practice observed in patients with MS have yet to be clarified.

The present study aimed to provide preliminary evidence regarding whether mindfulness-oriented meditation promotes personality changes, in terms of more adaptive and mature character traits, in individuals with MS, thus extending to this population the recent findings reported in healthy adults and other clinical populations.18 19 The direct impact of an 8-week mindfulness-oriented meditation intervention on the character scales of the TCI (self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence) and on the BFI personality traits (conscientiousness, neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and openness) was studied in a group of individuals with MS participating in the mindfulness training and in a “treatment-as-usual” control group. Similar to previous studies of mindfulness-oriented meditation in MS, we also tested the effects on anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as on mindfulness skills. We predicted higher scores in the character dimensions of the TCI (especially in self-directedness), particularly in the meditation group after compared with before the intervention; such a finding would suggest mindfulness-based therapies being beneficial for personality maturity of individuals with MS. For the BFI traits, we expected increased scores for the conscientiousness scale and decreased scores for the neuroticism scale in the meditation group16; finally we also hypothesized an effect of mindfulness-oriented meditation in reducing anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with MS.

Methods

Participants

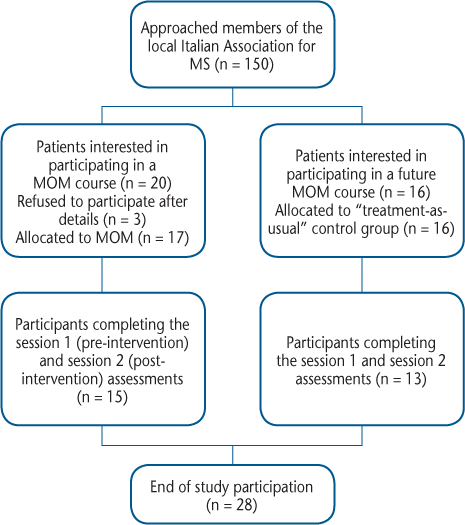

Thirty-three Italian patients with MS were included in the study. Seventeen participants took part in the mindfulness-oriented meditation training (mean [SD] age, 49.47 [9.92] years; 14 female). They were recruited through advertisements (eg, e-mail invitation) and by word of mouth from the approximately 150 members of the local Italian Association for MS located in Udine. Twenty interested patients contacted us, but three of them refused to participate after we explained the setting and duration of the course in more detail. The remaining 17 patients fulfilled the following criteria and were eligible for study inclusion: absence of previous experience with mindfulness-oriented meditation and with the outcome measures used in the study and absence of a current/past history of medical or neurologic illness other than MS. A treatment-as-usual group of eligible control participants was recruited from the same local MS association, through further advertisements, and by word of mouth including from the meditation participants. The control group consisted of 16 individuals with MS who were not involved in any meditation training; all these patients were interested in participating in a future mindfulness-oriented meditation course (mean [SD] age, 50.87 [11.02] years; 13 female) (Figure 1).

Participant flow

All the patients had a diagnosis of MS29 and were receiving treatment at a specialized MS care center in northeast Italy. Another criterion for the final inclusion of participants in the study was absence of a clinical relapse or corticosteroid pulse treatment within 6 weeks before evaluation and during the meditation course. No participant had a relapse during the study. The research protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the University-Hospital of Udine (n.80/2013/SPER). All the patients provided written informed consent.

Meditation Training and Experimental Procedures

The meditation training was inspired by the mindfulness-based stress reduction program23 and was based on the practice followed by Campanella et al.19 and Crescentini et al.18 30 31 The training consisted of eight weekly meetings of 2 hours each. Each meditation meeting involved three consecutive phases: 1) up to 30 minutes of active teaching on topics related to meditation, 2) 30 minutes of mindfulness-oriented meditation practice, and 3) a final discussion phase lasting up to 1 hour. Regarding active teaching, each meeting covered specific topics in line with the mindfulness-based stress reduction training (ie, introducing mindfulness, operating in automatic pilot mode, the power of being present, learning about our patterns of reactivity to stress and difficult emotions/sensations, coping with stress, using mindfulness to respond instead of reacting, mindfulness and communication, and accepting and nonjudging the present moment experience). The meditation practice remained the same throughout the course and was divided into three parts of approximately 10 minutes each: 1) mindfulness of breathing, 2) body scan, and 3) Vipassana meditation in which participants tried to nonjudgmentally observe their mental experience moment by moment. At the end of the first meeting, participants in the meditation group were given a CD containing a 30-minute recording of the voice of the instructor (the last author [F.F.], who has more than 5 years' experience in teaching mindfulness-oriented meditation interventions and more than 15 years' experience in personal mindfulness meditation) who guided the meditation through the same three steps described previously herein. Participants were asked to listen to the CD as an aid for homework assignments that consisted of 30 minutes of daily meditation practice. Meditation participants were required to keep a diary to write down the times and durations of their daily practice. The course was conducted in October and November 2015.

Two testing sessions (before and after the training for the meditation group and two temporally matched sessions for the control group) were organized to administer to all participants the questionnaires described later herein. In the meditation group, session 1 took place on average 1 day (range, 0–6 days) before the meditation course start date and session 2 took place on average 4.19 (range, 0–21) days after the course end date. The main outcome measures were the Italian adaptations of the 240-item TCI32 (character scales) (see also the study by Campanella et al.19) and the 44-item BFI.33 Each meditation and control participant completed the three character scales of the TCI (119 items total for the self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence subscales) and the BFI in two separate sessions (sessions 1 and 2). Moreover, in both testing sessions, before completing the TCI and the BFI, each participant was administered the following other self-report questionnaires. Trait and state anxiety levels were measured by using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI),34 a widely used 40-item, multiple-choice questionnaire. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),35 36 a 13-item self-report rating inventory, was used to measure symptoms of depression. Finally, mindfulness skills were measured using the 39-item Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ).37

Statistical Analysis

The overall matrix of the session 1 and session 2 FFMQ, STAI, BDI, TCI, and BFI data showed that 0.52% of the cells were left empty by patients with MS. For data analysis, these empty cells were replaced for each patient and for each questionnaire with the mean values of the relevant scale. The main analysis dealt with the character scales of the TCI. To have a common range of values for the two groups of patients with MS and for comparison with a healthy population, the individual raw scores concerning the three character scales of the TCI were converted to z scores on the basis of the age- and sex-matched average scores of a control sample of 320 healthy individuals ranging in age from 18 to 80 years (Table S3 in the study by Urgesi et al.38). The three character scales in the TCI globally measure three facets of the development and maturity of the self.19 Accordingly, a single mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed over the three TCI character scales, with scale (self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence) and session (session 1, session 2) as within-subject factors and group (meditation, controls) as a between-subject factor. In contrast, because the five scales of the BFI are assumed to measure more independent personality facets, they were analyzed separately by means of five mixed-model ANOVAs, each consisting of session (session 1, session 2) as a within-subject factor and group (meditation, controls) as a between-subject factor. For the analysis of the FFMQ, STAI-trait, STAI-state, and BDI data, we followed the same logic and ran a mixed-model ANOVA on the scores of each self-report measure, with session (session 1, session 2) as a within-subject factor and group (meditation, controls) as a between-subject factor. All post hoc tests were corrected for multiple comparisons according to the Duncan procedure. The significance threshold of P < .05 was used in all the statistical tests, and effect sizes are reported as partial eta squared (ηp 2).

Results

Participant Characteristics

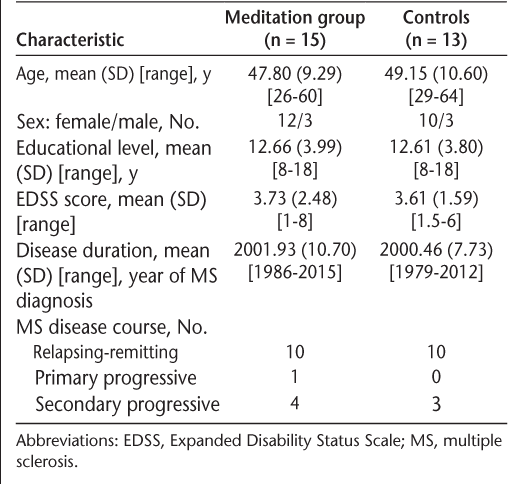

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups, and Table 2 reports the data from all the questionnaires. Overall, five female participants with MS (two from meditation group and three controls) were excluded from all the analyses reported in the present study because they did not complete the preintervention and postintervention evaluations. The reported results are, thus, based on two groups of 15 meditation and 13 control participants with MS. Independent-samples t tests showed that the two groups were matched for age (t 26 = 0.36, P = .72), years of education (t 26 = 0.03, P = .97), year of MS diagnosis (t 26 = 0.41, P = .68), Expanded Disability Status Scale scores39 (t 26 = 0.15, P = .88), sex (χ2 1 = 0.07, P = .79 [Yates correction applied]), and mean (SD) (range) days between the two testing sessions (meditation: 60.33 [5.31] [55–76] days; controls: 61.31 [4.49] [58–73] days; t 26 = 0.52, P = .60). The two groups were also comparable in terms of type of MS, with at least two-thirds of patients in both groups having relapsing-remitting MS. Finally, the 15 meditation participants attended a mean (SD) (range) of 6.93 (1.10) (5–8) of the 8 weekly meetings and meditated a mean (SD) (range) of 143.75 (41) (67.5–210) minutes per week.

Demographic and clinical data for 28 participants with MS

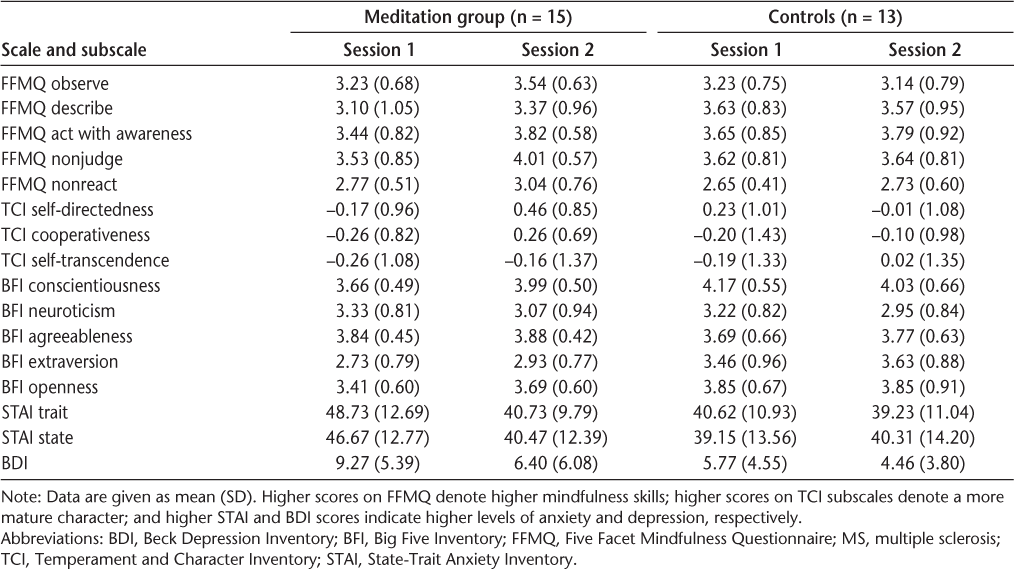

Self-report questionnaire scores in testing sessions 1 and 2 for meditation and control participants with MS

Effects of Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation

Effects on Mindfulness Skills

The ANOVA performed on the FFMQ scores involved session (session 1, session 2) and facet (observe, describe, act with awareness, nonjudge, and nonreact) as within-subject factors and group (meditation, controls) as a between-subject factor. The analysis showed significant main effects of session (F 1,26 = 6.13, P = .02, ηp 2 = 0.19) and facet (F 4,104 = 9.60, P < .01, ηp 2 = 0.27) and a significant interaction between session and group (F 1,26 = 4.89, P = .03, ηp 2 = 0.16). Post hoc tests for this interaction showed overall increased FFMQ scores at session 2 versus session 1 in the meditation (P < .01) but not control (P = .85) participants. No other main effects or interactions were significant (for all, F < 1.09, P > .36, ηp 2 < 0.05). The mindfulness-oriented meditation training thus led to general increased mindfulness skills in the meditation participants.

Effects on Personality Traits

The character scales of the TCI revealed that the profiles of the meditation and control participants in both testing sessions were close to those of the reference population38 (see Table 2, in which no mean score exceeds 0.46 SD above or below the average population scores in either of the two groups). The ANOVA performed on the three character scales showed a significant main effect of session (F 1,26 = 5.57, P = .02, ηp 2 = 0.18), a significant interaction between session and group (F 1,26 = 4.40, P = .04, ηp 2 = 0.14), and a significant three-way interaction involving the scale factor (F 2,52 = 3.98, P = .02, ηp 2 = 0.13) (the corresponding analysis on the nontransformed raw TCI data produced the same results). No other main effects or interactions were significant (for all, F < 0.67, P > .51, ηp 2 < 0.03). Post hoc tests performed for the three-way interaction disclosed a specific increase in SD and C character scores at session 2 versus session 1 in the meditation group (self-directedness: P < .01; cooperativeness: P = .01; self-transcendence: P = .64) but not in the control group (P = .20, P = .61, and P = .30, respectively). In other words, mindfulness-oriented meditation led to specific increases in self-maturity as reflected by the self-directedness and cooperativeness TCI scales in meditation participants.

Finally, we analyzed the scores of the five BFI personality traits (Table 2). Globally, the scale scores were in line with those of the normative sample33 and those reported in patients with MS.4 Critically, only the ANOVA performed on the conscientiousness scores showed a significant interaction between session and group (F 1,26 = 5.22, P = .03, ηp 2 = 0.17). Post hoc tests executed for this interaction showed a specific increase in conscientiousness scores after the training in meditation participants (P = .03) but not in controls (P = .33). The ANOVAs executed on the neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, and openness scores did not show a significant two-way interaction (for all, F < 2.43, P > .12, ηp 2 < 0.09).

In summary, the training led to specific increases in self-directedness, cooperativeness, and conscientiousness levels in meditation participants. Mindfulness-oriented meditation did not have a direct influence on self-transcendence, neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, or openness levels.

Effects on Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

For STAI-state, STAI-trait, and BDI data, we ran three separate 2 (session: session 1, session 2) × 2 (group: meditation, controls) repeated-measures ANOVAs. The analysis of STAI-trait data highlighted a main effect of session (session 2 < session 1; F 1,26 = 8.86, P < .01, ηp 2 = 0.25) and the two-way interaction session × group (F 1,26 = 4.40, P = .04, ηp 2 = 0.14). The main effect of group was not significant (F 1,26 = 1.50, P = .23, ηp 2 = 0.05). Post hoc analysis of the interaction showed lower STAI-trait scores at session 2 versus session 1 in meditation participants (P < .01 [P = .54 for controls]) (Table 2). The analysis of STAI-state data showed no significant main effects or interaction (for all, F < 3.01, P > .08, ηp 2 < 0.11). Finally, the analysis of BDI data showed a main effect of session (session 2 < session 1; F 1,26 = 11.17, P < .01, ηp 2 = 0.30) but not the main effect of group or the two-way interaction (for both, F < 2.23, P > .13, ηp 2 < 0.08).

The data thus showed specific effects of mindfulness-oriented meditation in reducing trait, but not state, anxiety in meditation participants. An effect of this meditation training was not found for depressive symptoms because both participant groups reported decreased BDI scores at session 2 versus session 1.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate whether mindfulness-oriented meditation affects the personality profiles of patients with MS. Moreover, variations in mindfulness skills and in anxiety and depression levels as due to this type of meditation were also assessed in the patients. We found an increase in the self-directedness and cooperativeness character dimensions of the TCI and in the conscientiousness trait of the BFI in the meditation group after the meditation training but not in the control group. Moreover, increased mindfulness skills and decreased trait anxiety were also observed in meditation participants after the intervention. In contrast, no particular effect of the meditation training on self-transcendence, neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, or openness to experience personality traits, as well as on state anxiety and depression levels, was found.

The modulation of MS patients' character and conscientiousness trait due to participation in mindfulness-oriented meditation training extends to this patient population similar results reported in other studies on healthy and clinical adults.18 19 These findings may be particularly important for fostering our understanding of the relationships between specific personality characteristics and MS. In the TCI, the self-directedness and cooperativeness character traits refer to one's own evaluation of the self and reflect the completeness (maturity) of the self at the intrapersonal (self-directedness mapping on concepts such as self-esteem and self-efficacy) and interpersonal (cooperativeness linked to empathy, tolerance, and compassion) levels. Both of theses character traits are the main determinants of the presence of personality disorders in the TCI: people with signs of immature character, namely, with low self-directedness and cooperativeness, are, indeed, at higher risk for personality disorders than people with better character maturity.40 41 In a similar manner, in the BFI model, the conscientiousness trait reflects an individual's inclination to adhere to socially prescribed norms and rules and to be goal directed and planful; this trait has been observed to be positively related to beneficial health-related behaviors and to better medication adherence.42

Of importance, a variety of studies on patients with MS have reported signs of immature character or low conscientiousness trait, which have also been connected with patients' cognitive and psychological status and stage of MS disease.4 11–13 43 For instance, Gazioglu et al.13 and, in particular, Kuloğlu et al.12 found low self-directedness scores (and social approval scores, a dimension of cooperativeness) in patients with MS, a finding that was held to relate with the potential for personality disorder and attributed to patients' avoidant and passive style of coping with problems. Thus, the present findings suggest that a potentially important factor of the beneficial effects of mindfulness-oriented meditation on MS could be linked to changes in personality/character traits. With this view, the development of mindful awareness—detached and nonjudgmental observation and acceptance of present moment experience—could protect patients with MS from personality disorders by boosting their character acting on aspects like sense of autonomy, maturity, reliability, purposefulness, and self and social acceptance.

From another perspective, the observed effect of mindfulness-oriented meditation on reducing (trait) anxiety in patients with MS corroborates previous similar findings25 26 44; nevertheless, these and other previous studies have also documented an effect of mindfulness meditation interventions on reducing depression symptoms in patients with MS.24–26 44 In the present study, both meditation and control participants reported decreased depression symptoms at session 2 versus session 1. Overall, these results support the need for future studies to further investigate the complex relationship between mental health (anxiety and depression) and personality characteristics in patients with MS participating in mindfulness-based interventions. This is particularly important if one considers that mood disorders can temporarily alter individuals' personality characteristics and that successful treatment of depression and anxiety in patients with MS could ameliorate personality disorders.4

The present study has several limitations. The first one concerns the restricted sample size; although it is similar to that of other studies of mindfulness-oriented meditation in MS,24–26 45 replication and extension of the present findings to larger samples of patients with MS is suggested. Another issue pertains to the lack of a follow-up session as well as an active control condition. Although the absence of a follow-up examination makes it difficult to establish long-term stability of the psychological changes observed in the present study, the use of a treatment-as-usual control condition (which is the standard in studies of this type of meditation in MS22 24–26 45) prevents us from definitely attributing to mindfulness practice the observed changes. Future studies could take advantage of follow-up sessions and active control conditions, as well as better randomization procedures.46 Moreover, they could also benefit from using better control procedures in which the people who assess the intervention remain blind to group allocation (which was not the case in the present study). Finally, together with the use of self-report questionnaires, it is advisable that future studies also use other measures of the effects of mindfulness-oriented meditation in MS, such as psychophysiological measurements.47 48 For example, heart rate variability (HRV), a measure of beat-to-beat variability in heart rate that is mediated by the autonomic nervous systems, could be measured before and after mindfulness-oriented meditation training. Increased HRV is related to well-being and positive affect, whereas it is reduced in patients with depression and anxiety.47 48 Recent studies in nonclinical populations also found that brief trainings in mindfulness meditation can lead to increased HRV.47 Thus, future studies could test whether mindfulness-oriented meditation reduces anxiety (as measured by self-report questionnaires) and increases HRV in patients MS. Regarding self-report measures, because the BDI and the FFMQ may include items that might not be appropriate for each patient with MS or can be effects of MS rather than reflections of depression and mindfulness (eg, fatigue in the BDI and being mindful when walking in the FFMQ), future research should attempt to extend the present findings using other widely used and validated measures of depression and mindfulness.44 49

In conclusion, the present study shows the importance of mindfulness-oriented meditation in promoting more adaptive and mature personality profiles of people with MS. We found that an 8-week mindfulness-based intervention led to increased character maturity and conscientiousness in a group of participants with MS; these results could, in turn, suggest a potential role of mindfulness meditation in reducing the risk of personality disorders in MS. More generally, these findings support the possible usefulness of continuing to assess and treat personality characteristics in patients with MS, both in the context of mindfulness-based interventions and with more traditional forms of psychotherapy, with the aim of enhancing patient adherence to medical/psychological treatment, prognosis, and quality of life.

PRACTICE POINTS

Personality changes, a common symptom in patients with MS, are often associated with poor coping and reduced quality of life.

We exposed patients with MS to an 8-week mindfulness-oriented meditation course and evaluated the effects on personality traits and anxiety and depression symptoms.

Mindfulness-oriented meditation led to changes in personality/character traits reflecting the maturity of the self at the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels and also led to decreases in trait anxiety.

Financial Disclosures:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:938–952.

Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1139–1151.

Guimarães J, Sá MJ. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2012;3:74.

Bruce JM, Lynch SG. Personality traits in multiple sclerosis: association with mood and anxiety disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:479–485.

Stathopoulou A, Christopoulos P, Soubasi E, Gourzis P. Personality characteristics and disorders in multiple sclerosis patients: assessment and treatment. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22:43–54.

Strober LB. Personality in multiple sclerosis (MS): impact on health, psychological well-being, coping, and overall quality of life. Psychol Health Med. 2016;1–10.

Costa P, McCrae R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992.

Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:975–990.

Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic, DM, Wetzel RD. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A Guide to Its Development and Use. St Louis, MO: Center for Psychobiology of Personality, Washington University; 1994.

Christodoulou C, Deluca J, Johnson SK, et al. Examination of Cloninger's basic dimensions of personality in fatiguing illness: chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:597–607.

Schwartz ES, Chapman BP, Duberstein PR, et al. The NEO-FFI in multiple sclerosis: internal consistency, factorial validity, and correspondence between self and informant reports. Assessment. 2011;18:39–49.

Kuloğlu M, Saglam S, Korkmaz S, et al. Temperament and character traits and alexithymia in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neuropsychiatr. 2013;50:34–39.

Gazioglu S, Cakmak VA, Ozkorumak E, et al. Personality traits of patients with multiple sclerosis and their relationship with clinical characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:408–411.

Didonna F. Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2009.

Chiesa A, Serretti A. A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1239–1252.

Giluk TL. Mindfulness, big five personality, and affect: a meta-analysis. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;47:805–811.

Crescentini C, Capurso V. Mindfulness meditation and explicit and implicit indicators of personality and self-concept changes. Front Psychol. 2015;6:44.

Crescentini C, Matiz A, Fabbro F. Improving personality/character traits in individuals with alcohol dependence: the influence of mindfulness-oriented meditation. J Addict Dis. 2015;34:75–87.

Campanella F, Crescentini C, Urgesi C, Fabbro F. Mindfulness-oriented meditation improves self-related character scales in healthy individuals. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:1269–1278.

Crescentini C, Urgesi C, Fabbro F, Eleopra R. Cognitive and brain reserve for mind-body therapeutic approaches in multiple sclerosis: a review. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2014;32:575–595.

Levin AB, Hadgkiss EJ, Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA. Meditation as an adjunct to the management of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Res Int. 2014;2014:704691.

Simpson R, Booth J, Lawrence M, et al. Mindfulness based interventions in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:15.

Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:144–156.

Burschka JM, Keune PM, Oy UH, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions in multiple sclerosis: beneficial effects of Tai Chi on balance, coordination, fatigue and depression. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:165.

Bogosian A, Chadwick P, Windgassen S, et al. Distress improves after mindfulness training for progressive MS: a pilot randomised trial. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1184–1194.

Kolahkaj B, Zargar F. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on anxiety, depression and stress in women with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2015;4:e29655.

Levin AB, Hadgkiss EJ, Weiland TJ, et al. Can meditation influence quality of life, depression, and disease outcome in multiple sclerosis? findings from a large international web-based study. Behav Neurol. 2014;2014:916519.

Schirda B, Nicholas JA, Prakash RS. Examining trait mindfulness, emotion dysregulation, and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Health Psychol. 2015;34:1107–1115.

Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83:278–286.

Crescentini C, Urgesi C, Campanella F, et al. Effects of an 8-week meditation program on the implicit and explicit attitudes toward religious/spiritual self-representations. Conscious Cogn. 2014;30:266–280.

Crescentini C, Chittaro L, Capurso V, et al. Psychological and physiological responses to stressful situations in immersive virtual reality: differences between users who practice mindfulness meditation and controls. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;59:304–316.

Battaglia M, Bajo S. Temperament and character inventory. In: Conti L, ed. Repertorio delle scale di valutazione in psichiatria. Firenze, Italy: SEE; 2000.

Ubbiali A, Chiorri C, Hamption P, Donati D. Italian Big Five Inventory: psychometric properties of the Italian adaptation of the Big Five Inventory (BFI). Boll Psicol Appl. 2013;266:37–48.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, et al. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects. New York, NY: Hoeber Medical Division, Harper & Row; 1967.

Beck A, Beck R. Screening depressive patients in family practice: a rapid technic. Postgrad Med. 1972;11:561–579.

Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, et al. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45.

Urgesi C, Aglioti SM, Skrap M, Fabbro F. The spiritual brain: selective cortical lesions modulate human self-transcendence. Neuron. 2010;65:309–319.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452.

Svrakic DM, Whitehead C, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Differential diagnosis of personality disorders by the seven-factor model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:991–999.

Svrakic DM, Draganic S, Hill K, et al. Temperament, character, and personality disorders: etiologic, diagnostic, treatment issues. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:189–195.

Molloy GJ, O'Carroll RE, Ferguson E. Conscientiousness and medication adherence: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47:92–101.

Benedict RH, Priore RL, Miller C, et al. Personality disorder in multiple sclerosis correlates with cognitive impairment. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13:70–76.

Grossman P, Kappos L, Gensicke H, et al. MS quality of life, depression, and fatigue improve after mindfulness training: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2010;75:1141–1149.

Tavee J, Rensel M, Pope Planchon S, Stone L. Effects of meditation on pain and quality of life in multiple sclerosis and polyneuropathy: a controlled study. Int J MS Care. 2011;13:163–168.

MacCoon DG, Imel ZE, Rosenkranz MA, et al. The validation of an active control intervention for Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Behav Res Ther. 2012;50:3–12.

Krygier JR, Heathers JAJ, Shahrestani S, et al. Mindfulness meditation, well-being, and heart rate variability: a preliminary investigation into the impact of intensive Vipassana meditation. Int J Psychophysiol. 2013;89:305–313.

Chalmers JA, Quintana DS, Abbott MJ, Kemp AH. Anxiety disorders are associated with reduced heart rate variability: a meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:80.

Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmuller V, et al. Measuring mindfulness: the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40:1543–1555.