Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Somatic Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety in People with Multiple Sclerosis

CME/CNE Information

Activity Available Online:

To access the article, post-test, and evaluation online, go to http://www.cmscscholar.org.

Target Audience:

The target audience for this activity is physicians, physician assistants, nursing professionals, and other health-care providers involved in the management of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Learning Objectives:

1) Identify the somatic symptoms of depression and anxiety and when somatic symptoms of depression and anxiety should be assessed in people with multiple sclerosis (MS).

2)Identify the most useful clinical cutoff score on the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 to assess for depression in individuals with MS.

Accreditation Statement:

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and Delaware Media Group. CMSC is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Physician Credit

The CMSC designates this journal-based activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s) ™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Nurse Credit

The CMSC designates this enduring material for 1.0 contact hours (none in the area of pharmacology).

Disclosures:

Editor in Chief of the International Journal of MS Care (IJMSC), has served as Physician Planner for this activity. He has received royalties from Springer Publishing, intellectual property rights/patent holder from Biogen, and consulting fees from Ipsen Pharma and has performed contracted research for Biogen, Adamas Pharmaceuticals, and Acorda Therapeutics.Francois Bethoux, MD,

has served as reviewer for this activity. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.Laurie Scudder, DNP, NP,

received salary from Pacific Rehabilitation Centers in Puyallup, WA, for conducting psychological evaluations (once weekly, July 2016–August 2017).Salene M.W. Jones, PhD,

, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.Rana Salem, MA

, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.Dagmar Amtmann, PhD

The peer reviewers for the IJMSC have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The staff at the IJMSC, CMSC, and Delaware Media Group who are in a position to influence content have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Note: Disclosures listed for authors are those applicable at the time of their work on this project and within the previous 12 months.

Method of Participation:

Release Date: June 1, 2018

Valid for Credit Through: June 1, 2019

In order to receive CME/CNE credit, participants must:

1) Review the continuing education information, including learning objectives and author disclosures.

2) Study the educational content.

3) Complete the post-test and evaluation, which are available at http://www.cmscscholar.org.

Statements of Credit are awarded upon successful completion of the post-test with a passing score of >70% and the evaluation.

There is no fee to participate in this activity.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use:

This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not approved by the FDA. CMSC and Delaware Media Group do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of CMSC or Delaware Media Group.

Disclaimer:

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any medications, diagnostic procedures, or treatments discussed in this publication should not be used by clinicians or other health-care professionals without first evaluating their patients' conditions, considering possible contraindications or risks, reviewing any applicable manufacturer's product information, and comparing any therapeutic approach with the recommendations of other authorities.

Abstract

Background:

People with multiple sclerosis (MS) are at increased risk for depression and anxiety. The symptoms of MS are often similar to the somatic or physical symptoms of depression and anxiety (fatigue, trouble concentrating). This study examined whether MS symptoms and effects biased the assessment of somatic symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Methods:

People with MS (n = 513) completed a survey about MS symptoms, treatments, and distress. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 assessed depression, and the patient-report version of the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders assessed anxiety. Participants were grouped into low versus high MS symptoms based on self-reported symptoms and as high versus low disability by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Groups were compared using differential item functioning analysis.

Results:

No bias was found on somatic symptoms of depression comparing high versus low MS symptom groups (P > .15) or comparing groups based on EDSS scores (P > .29). Two anxiety symptoms (fatigue and muscle tension) showed bias comparing high versus low MS symptom groups (P < .01) and comparing high versus low groups based on EDSS scores (P ≤ .01). Intraclass correlations suggested a small effect due to bias in the somatic symptoms of anxiety.

Conclusions:

Somatic symptoms of depression are unlikely to be biased by MS symptoms. However, the use of certain somatic symptoms to assess anxiety may be biased for those with high MS symptoms.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurologic disease characterized by cognitive impairment, fatigue, spasticity, weakness, and numbness,1 among other symptoms. The disease can have a relapsing-remitting pattern, with periods of symptoms followed by periods with few or no symptoms, or a progressive pattern, in which symptoms steadily worsen over time.1 Often, people with MS report lower quality of life and feelings of depression and anxiety more so than the general population.2 3 One problem with addressing depression and anxiety in MS is the potential confounding of the symptoms of MS with the somatic or physical symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Depression is a psychological disorder characterized by depressed mood or lack of interest in activities as well as the following other symptoms: fatigue, sleep disturbance, changes in appetite or weight, feelings of worthlessness, trouble concentrating, psychomotor agitation or retardation, and thoughts of suicide.4 Some of the four somatic symptoms of depression (fatigue, sleep disturbance, appetite/weight changes, trouble concentrating) may be due to MS and not depression in people with MS. This could lead to overestimating and biasing the measurement of depression in MS because the MS symptoms could confound the somatic symptoms of depression. Simply excluding somatic symptoms would not be the best solution to this problem because women5 and people from certain cultures6 are often more likely to report somatic symptoms of depression, and somatic symptoms are an important marker of depression.7 Excluding somatic symptoms when assessing depression in MS may cause these groups to not receive needed medical care for depression. Instead, a robust literature determining empirically whether somatic symptoms are biased by MS symptoms is needed.

Previous research comparing people with MS with a community sample has suggested that measures of depression are not biased on the somatic symptoms.8 Another way to establish whether somatic symptoms are an appropriate measure of depression is to compare people with MS who are likely to have a confounding factor (higher level of disability, more MS symptoms) with those who are less likely to have a confounder. Similar work in people with cancer has suggested that cancer treatments and symptoms do not confound the measurement of somatic symptoms of depression.9 However, this finding has not been established in people with MS.

Anxiety refers to a feeling of nervousness and apprehension about something bad that might happen.10 11 Anxiety disorders are often accompanied by physical symptoms such as muscle tension, fatigue, and trouble sleeping.4 Similar to depression, these symptoms may be confounded by the physical symptoms of MS or MS treatment, and this would complicate measurement of anxiety in people with MS. Less work has been conducted to investigate the potential for bias in somatic symptoms of anxiety than in somatic symptoms of depression.

This study examined whether level of MS symptoms and disability confounded or biased the measurement of somatic symptoms of depression and anxiety in a sample of people with MS. As clinicians address depression and anxiety in people with MS, they need to be confident in the measurement of the symptoms over time and know that changes reflect the psychiatric treatment and not variation in MS symptoms and the disease effects. If somatic symptoms are more indicative of MS symptoms than of anxiety or depression, this would argue against their use in monitoring depression and anxiety or would suggest a need to change cutoff scores for likely major depressive disorder or an anxiety disorder. It would also support the practice of removing somatic items from symptom measures of depression and anxiety for people with MS. If somatic symptoms are not substantially biased by these factors, this would add further evidence for their use without modification in assessing depression and anxiety in MS.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

A secondary analysis was completed of data from a survey of people with MS. People with MS who were members of the Greater Northwest Multiple Sclerosis Society or who had participated in previous studies were invited to complete the initial survey. Of the 1270 people who completed the first survey, 582 were randomly selected and invited to complete a subsequent survey. Data were used from the second survey (completed in 2007), of which 513 were completed. Participants could complete surveys on paper or online, and each received $25 for doing so. If survey questions were left blank, study staff attempted to call participants to ensure that the blanks were intentional and, if not, to obtain the responses. All the study procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Washington, Human Subjects Division. All the participants provided informed consent. For participants who reported suicidal ideation on the questionnaires, study staff called them, assessed their current state, and referred them to treatment if needed.

Measures

Demographic and MS Characteristics

Respondents indicated their age, sex, and race/ethnicity. They also noted their year of diagnosis of MS for calculating time since diagnosis and their type of MS (relapsing-remitting vs. progressive and other types). Respondents also indicated whether they were currently taking first-line disease-modifying therapies (interferon beta-1a [Avonex; Biogen, Cambridge, MA; or Rebif; EMD Serono Inc, Rockland, MA], interferon beta-1b [Betaseron; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Montville, NJ], or glatiramer acetate [Copaxone; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, North Wales, PA]), second-line disease-modifying therapies (natalizumab [Tysabri; Biogen] or mitoxantrone [Novantrone; EMD Serono Inc]), or other MS treatments, including azathioprine (Imuran; Prometheus Laboratories, Inc, San Diego, CA), methotrexate (Trexall; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd), or cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan; Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ), a scheduled intravenous corticosteroid treatment, and other treatments.

Depression

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Appendix S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org).12 This measure consists of nine items corresponding to the symptoms of major depressive disorder4: depressed mood, anhedonia (lack of interest), sleep problems, fatigue, unintended appetite or weight changes, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, trouble concentrating, psychomotor retardation or agitation (moving slowly or more quickly than usual), and suicidal ideation. Each item is rated on the following scale for the previous 2 weeks: 0 = not at all; 1 = several days; 2 = more than half the days; and 3 = nearly every day. Items are summed to create a total score, with higher scores meaning more severe depressive symptoms. The measure has been shown to have one factor13–16 and to have good reliability and validity,12 including in MS.17

Anxiety

The Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) screening measure was developed to screen for psychological disorders in medical practices, and this study used the patient-report version to assess anxiety during the previous 4 weeks (Appendix S1).18 This measure asks participants to rate the following symptoms of anxiety: worrying or feeling nervous, feeling restless, fatigue, muscle tension, sleep problems, trouble concentrating, and being more irritable. Participants rated each item as 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), or 2 (more than half the days). Higher scores indicate more anxiety, and the measure has shown adequate reliability and validity.18 We chose this anxiety measure because it includes somatic symptoms, unlike other measures, such as the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale.

MS Symptoms

Respondents rated the interference of 16 MS symptoms (Appendix S1). A scale was created specifically for this survey, and each symptom was rated as follows: 0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = somewhat, 3 = quite a bit, and 4 = very much. The following symptoms were rated: heat sensitivity, difficulty learning new things, memory loss, numbness anywhere in the body, problems with bowel or bladder, imbalance, problems thinking, sexual problems, adverse effects of medications, slurred speech, spasticity, swallowing problems, tremor, vision loss, weakness in arms, and weakness in legs. The Cronbach α for the 16 symptoms was 0.88.

Expanded Disability Status Scale

Participants completed the mobility subscale of the self-report version of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS; Appendix S1).19 The questions asked participants about their ability to walk and the distance they could walk, as well as what assistive mobility devices they used (cane, wheelchair). The full EDSS gives respondents a score ranging from 0 (no disability) to 10 (death). Since only the mobility subscale was used in this study, we categorized participants as being in the minimal (≤4), intermediate (4.5–6.5), or advanced (≥7) disability group. The measure has shown good reliability and validity, including concordance with physician-rated measures.19

Statistical Analyses

Differential item functioning (DIF) analysis was used to test for bias in somatic symptoms between high and low MS symptom groups and between groups with lower and higher levels of disability. Few participants endorsed suicidal ideation, so this item was excluded from the analyses because adequate parameters could not be estimated. Owing to the small sample size, each symptom of depression and anxiety was dichotomized into not present (score of 0) and present (score of 1–3 for depression and 1–2 for anxiety). Therefore, a two-parameter logistic model was used for the DIF analysis.20 The model constructs a probability function for each item using a logistic model in which the amount of the construct, in this case depression or anxiety, is plotted against the probability of endorsing an item (symptoms in this case). Some items or symptoms need less of the construct before probability of endorsing the item increases, and other items need more of the construct before probability goes up. The model involves two parameters to model this probability: slope and threshold. The slope refers to how accurately the item measures the construct or how accurately we can say a person is above or below a certain level of the construct (such as depression or anxiety) based on saying yes or no to the item. The threshold refers to that certain level and indicates how much of the construct the person likely has, given endorsement of an item or symptom.

In DIF analysis, separate probability functions are constructed between groups, controlling for the level of the construct. Differences in slope and threshold are then tested using the Wald χ2 test.21 The DIF analysis requires that certain items be specified as the anchors so that the level of the construct can be estimated. Nonsomatic symptoms (depressed mood, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, psychomotor retardation or agitation, worrying or feeling nervous, feeling restless, being more irritable) were the anchor for the present analyses, whereas somatic symptoms were tested for DIF (sleep problems, fatigue, unintended appetite or weight changes, trouble concentrating, muscle tension). Significant χ2 values for the somatic symptoms would indicate potential bias or confounding by MS symptoms. Two analyses were run for the PHQ-9 (disability level, MS symptoms), and two DIF analyses were run for the PRIME-MD–Anxiety (disability level, MS symptoms). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was used to assess model fit.

Groups for comparison were created using the symptom and disability questions. Participants' ratings of all symptoms were averaged, and then the median was used to split the sample into a high symptom group (n = 263) and a low symptom group (n = 250). For disability status, people scoring 4 or less on the EDSS (the minimal group, n = 163) were compared with those who scored higher than 4 (the intermediate and advanced groups, n = 344). Due to the number of comparisons, an α level of .01 was used instead of .05. IRTPRO 2.0 (SSI Inc, Skokie, IL) was used to conduct the DIF analyses. When DIF was found, item response theory scores were calculated both accounting for statistically significant DIF and not accounting for DIF. The scores accounting for DIF and not accounting for DIF were compared using a two-way, random-effects, absolute agreement intraclass correlation to determine the effect size of the DIF.22

For the PHQ-9, a score of 10 or higher indicates a possible depressive disorder, and a score of 5 to 9, inclusive, indicates mild depression.12 We calculated how many participants would be classified as possibly having a depressive disorder using both the 10- and 5-point cutoffs when only somatic symptoms were present. This would help indicate the severity of any confounding from somatic symptoms.

Results

Study Participants

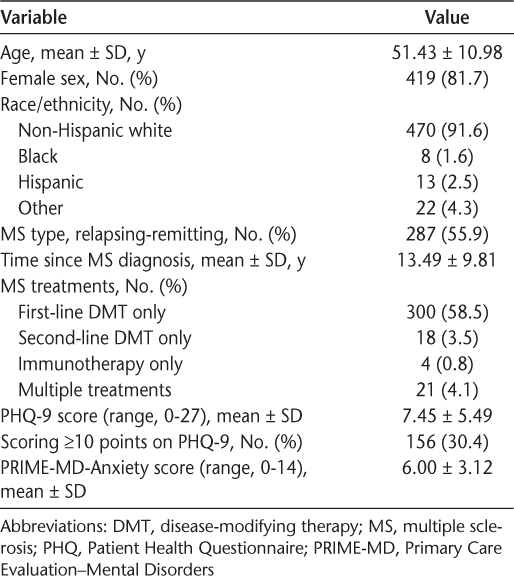

The characteristics of the sample were consistent with those in other studies of MS.23 Most of the 513 participants were female (81.7%), white (91.6%), and middle aged (mean age, 51 years) (Table 1). Slightly more than half of the sample (55.9%) had relapsing-remitting MS, and most were more than a decade (mean, 13.49 years) post–MS diagnosis.

Demographic and disease characteristics of the 513 study participants

MS Symptoms

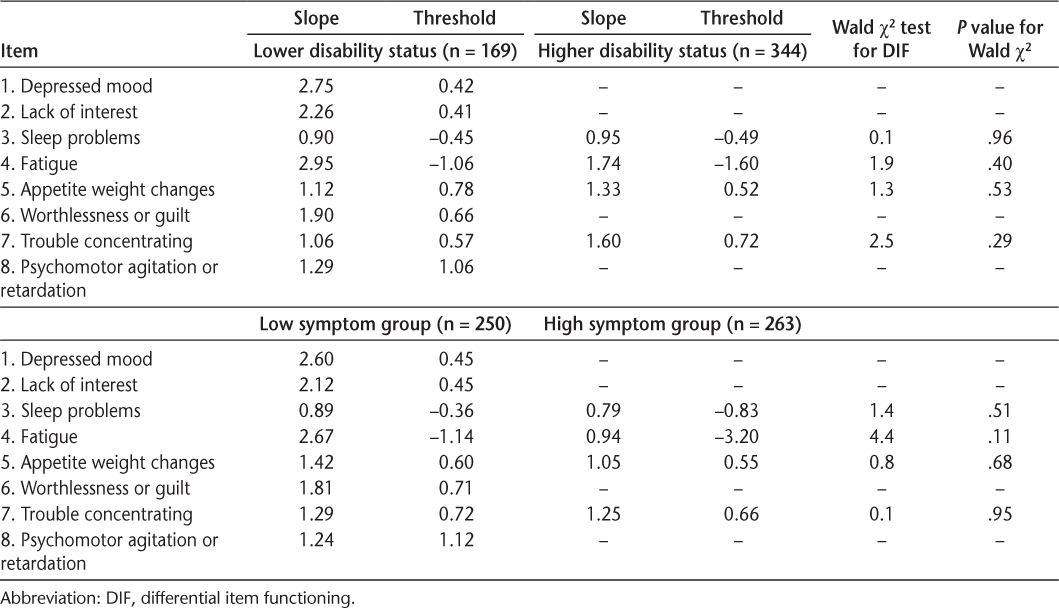

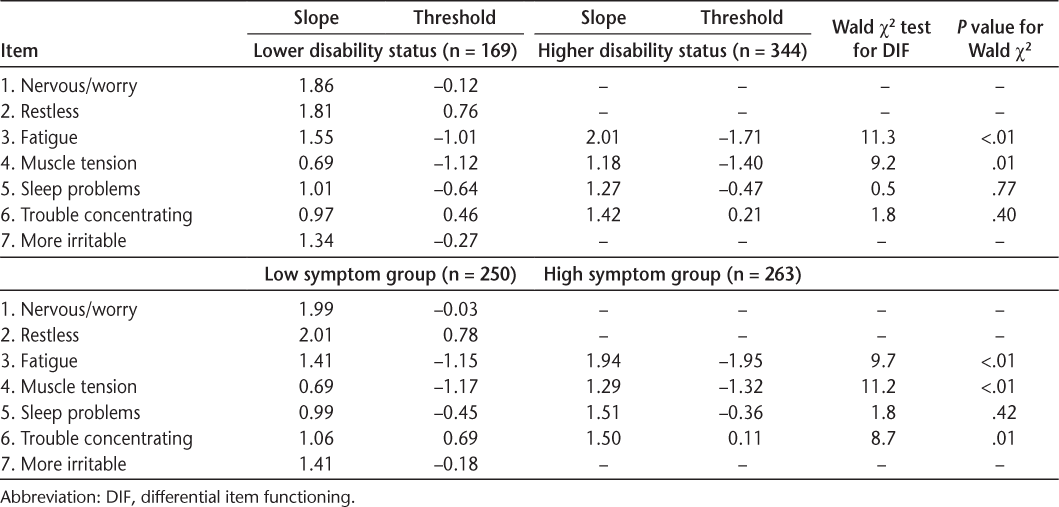

Somatic symptoms did not show bias by level of MS symptoms, with some notable exceptions for anxiety. Both models fit well (RMSEA for depression = 0.03 and for anxiety = 0.02). The somatic symptoms of depression did not show bias (DIF) by high versus low levels of MS symptoms (Table 2). However, two anxiety somatic symptoms, fatigue and muscle tension, did show statistically significant DIF (Table 3). Further examination showed that the slopes did not differ (P > .20) but the thresholds likely differed (P < .01). The intraclass correlation was 0.91 between scores not accounting for DIF and scores accounting for DIF in the thresholds. This result suggests that for people with high MS symptoms, endorsing fatigue or muscle tension indicates lower levels of anxiety than when people with low MS symptoms endorse fatigue or muscle tension and controlling for the overall level of anxiety.

Parameters and tests of significance from the two-parameter model DIF for depression

Parameters and tests of significance from the two-parameter model DIF for anxiety

Disability Status

Disability status did not bias any somatic symptom for depression but possibly biased a few symptoms for anxiety. Both models fit well (RMSEA for depression = 0.02 and for anxiety = 0.03). As reported in Table 2, the slope and thresholds for the somatic symptoms of depression did not differ between those with a lower disability status and those with a higher disability status. As shown in Table 3, the slope and thresholds for the anxiety somatic symptoms did not differ between disability status groups except for fatigue (P < .01). For anxiety, muscle tension showed some DIF but it did not quite reach significance (P = .01). Further inspection showed that the slopes did not differ for fatigue and muscle tension (P > .19) but the thresholds likely differed (P < .01). The intraclass correlation was 0.94 between scores, accounting for the DIF in thresholds and scores not accounting for any DIF.

Positive Screens for Depression

The PHQ-9 scores showed little chance of incorrectly identifying someone as depressed using the 10-point cutoff and a small chance using the 5-point cutoff. Thirty-seven participants (7.2%) scored 10 points or higher on somatic symptoms on the PHQ-9, but all of these participants reported some psychological symptoms. A large minority of the sample, 187 of 513 (36.5%), reported somatic symptoms of 5 through 9 points on the PHQ-9. A small number of this subgroup, 17 of 187 (9.1%; or 3.3% of total sample), reported only somatic symptoms and no psychological symptoms. These results suggest that there is little risk of misclassifying people as depressed from only somatic symptoms using the 10-point cutoff and only a small risk using the 5-point cutoff.

Discussion

Overall, somatic symptoms of depression did not show bias when people with high MS symptoms or disability were compared with those with low MS symptoms or disability. In contrast, two somatic symptoms of anxiety (fatigue and muscle tension) showed bias when comparing the high MS symptom group with the low MS symptom group, whereas sleep and concentration problems did not show bias. Similarly, fatigue and muscle tension showed bias in the analyses of anxiety comparing people with a lower disability level with those with a higher disability level. The intraclass correlations between scores accounting for and not accounting for the differences showed a small effect due to bias. When using the 10-point cutoff of the PHQ-9, no participant scored above the cutoff on somatic symptoms alone. A few participants reported somatic symptoms in the 5- to 9-point range on the PHQ-9 without any psychological symptoms. These results suggest that somatic symptoms can be used for depression assessment and can be used for anxiety assessment with some caveats.

The lack of bias in somatic symptoms of depression is consistent with previous research showing no bias when comparing a sample with neurologic disease with controls, and with previous work in cancer.8 9 24 It would be best to use 10 points as the cutoff on the PHQ-9, rather than 5 points, for people with MS given that no participants scored 10 points or higher on somatic symptoms alone but a few scored 5 points or higher on somatic symptoms alone. That fatigue showed bias with anxiety but not with depression is particularly interesting. This could be due to fatigue being a cardinal symptom of depression4 but not necessarily anxiety. Sleep and concentration problems can both be used to assess depression and anxiety because neither showed bias.

These results and the previous literature suggest that somatic symptoms can continue to be used to assess depression in individuals with MS. For anxiety, some somatic symptoms are unlikely to be biased by MS severity, but a possibility exists that MS symptoms may bias fatigue and muscle tension. However, bias in somatic symptoms of anxiety has been less studied than depression, so further research is needed, and the bias effects were small. Researchers and clinicians may want to consider anxiety measures that do not have somatic symptoms, such as the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale,25 26 which has been validated in MS.27

The limitations of this study suggest future areas of research. First, the sample was too small to assess bias in the level of somatic symptoms—only the presence or absence of the symptom. Future research with larger samples is needed to determine whether MS symptoms may bias level (intensity or severity) of somatic symptoms. Because MS is a unique neurologic condition with unique treatments, results may not translate to other diseases. We also were unable to examine bias from MS treatment due to the sample size. Future studies with larger samples should attempt to assess for bias from specific medications and therapies for MS. Our measure of MS symptoms was also unvalidated and created specifically for this survey. Due to the long time since MS diagnosis for this sample, this study should be replicated in people closer to diagnosis because the experience of those recently diagnosed may differ.28 Although further research is indicated, the results of this study show that somatic symptoms of depression and, to a certain extent, anxiety can be reliably measured in people with MS.

PRACTICE POINTS

In a sample of 513 people with MS (mean time since diagnosis, 13.49 years), somatic symptoms of depression were not biased by MS symptom severity. Somatic symptoms of anxiety were either not biased or showed small bias due to MS symptoms.

Providers screening for depression or monitoring depression treatment effectiveness in MS should continue to use measures that include somatic symptoms of depression.

Providers addressing anxiety in MS can continue to use measures that include somatic symptoms but should consider an anxiety measure that uses only psychological symptoms.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the participants and study personnel.

References

Sadovnick AD, Ebers GC. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: a critical overview. Can J Neurol Sci. 1993;20:17–29.

Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. A review of psychological correlates of adjustment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:141–153.

Chwastiak L, Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, Sullivan M, Bowen JD, Kraft GH. Depressive symptoms and severity of illness in multiple sclerosis: epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1862–1868.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Silverstein B. Gender difference in the prevalence of clinical depression: the role played by depression associated with somatic symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:480–482.

Ryder AG, Yang J, Zhu X, et al. The cultural shaping of depression: somatic symptoms in China, psychological symptoms in North America? J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:300–313.

Tylee A, Gandhi P. The importance of somatic symptoms in depression in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7:167–176.

Chung H, Kim J, Askew RL, Jones SM, Cook KF, Amtmann D. Assessing measurement invariance of three depression scales between neurologic samples and community samples. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1829–1834.

Jones SM, Ludman EJ, McCorkle R, et al. A differential item function analysis of somatic symptoms of depression in people with cancer. J Affect Disord. 2015;170:131–137.

Andrews G, Hobbs MJ, Borkovec TD, et al. Generalized worry disorder: a review of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder and options for DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:134–147.

Barlow DH. Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2004.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613.

Cameron IM, Crawford JR, Lawton K, Reid IC. Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:32–36.

Dum M, Pickren J, Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Comparing the BDI-II and the PHQ-9 with outpatient substance abusers. Addict Behav. 2008;33:381–387.

Hansson M, Chotai J, Nordstöm A, Bodlund O. Comparison of two self-rating scales to detect depression: HADS and PHQ-9. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:e283–e288.

Kalpakjian CZ, Toussaint LL, Albright KJ, Bombardier CH, Krause JK, Tate DG. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in spinal cord injury: an examination of factor structure as related to gender. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:147–156.

Amtmann D, Kim J, Chung H, et al. Comparing CESD-10, PHQ-9, and PROMIS depression instruments in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59:220–229.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744.

Bowen J, Gibbons L, Gianas A, Kraft GH. Self-administered Expanded Disability Status Scale with functional system scores correlates well with a physician-administered test. Mult Scler. 2001;7:201–206.

Birnbaum A. Some latent trait models and their use in inferring an examinee's ability. In: Lord FM, Novick MR, eds. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1968:395–479.

Lord FM. A study of item bias, using item characteristic curve theory. In: Portinga YH, ed. Basic Problems in Cross-Cultural Psychology. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger; 1977:19–29.

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428.

Bruce JM, Arnett P. Clinical correlates of generalized worry in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2009;31:698–705.

Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Krause JS, Tulsky D, Tate DG. Symptoms of major depression in people with spinal cord injury: implications for screening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1749–1756.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–359.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097.

Terrill AL, Hartoonian N, Beier M, Salem R, Alschuler K. The 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale as a tool for measuring generalized anxiety in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:49–56.

Janssens AC, van Doorn PA, de Boer JB, et al. Anxiety and depression influence the relation between disability status and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003;9:397–403.