Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Research-to-Practice Gaps in Multiple Sclerosis Care for Patients with Subjective Cognitive, Mental Health, and Psychosocial Concerns in a Canadian Center

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

People with multiple sclerosis (MS) are at increased risk for cognitive impairment, mental health concerns, and psychosocial issues, which can negatively affect disease outcomes and quality of life. Current MS care guidelines recommend integrated interdisciplinary services to address these concerns; however, issues can be overlooked during routine care. To date, there is inadequate research on how often these issues are identified and addressed during routine MS care.

Methods:

One hundred medical records were randomly selected and reviewed (55 relapsing-remitting MS, 17 secondary progressive MS, 8 primary progressive MS, and 20 other or subtype not indicated). All visits to, and contacts with (ie, telephone, e-mail), an MS clinic over 1 year were included in the analysis to determine the proportion of patients presenting with cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial concerns and the proportion of patients offered associated services.

Results:

Of the 25 patients with at least one identified concern, treatment recommendations occurred for 13 (52%). Rates of identification of cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial concerns in standard clinical practice were significantly lower than the identified prevalence in epidemiologic studies. Demographic factors had no bearing on who was offered treatment. Patients with concerns access MS clinic services more often than those without.

Conclusions:

Discrepancies between reported and expected frequencies may be due to overreliance on patient self-disclosure and concerns by the health care team that inadequate resources are available to address issues. An interdisciplinary team model may help address these issues.

Physical outcomes in people with multiple sclerosis (MS) contribute less to health-related quality of life (HRQOL) than do cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial variables.1 Depression is the strongest predictor of low HRQOL, followed by cognitive impairment, pain, lack of support/autonomy, fatigue, anxiety, and rapid disease course.2 It can be difficult for patients to communicate these needs during routine care and obtain treatment.3

Cognitive impairment (present in up to 70% of people with MS4) leads to a greater likelihood of psychosocial challenges5 6 and disability.7 Methods exist to assess cognition when neuropsychological services are unavailable. The Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS (BICAMS) can be administered by nonspecialized staff.8–13 Despite this, cognitive issues are not adequately addressed, as traditional neurologic practice dominates over interdisciplinary approaches.2 7 14

Up to 50% of people with MS experience depression.14–16 Other mental health concerns (anxiety, psychosis, bipolar disorder, suicide, etc17–19) are also prevalent and negatively affect HRQOL.15 19 20 Identifying mental health issues is complicated given overlap with MS symptoms,21 but validated questionnaires can help (eg, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]22 and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9]23). Nonetheless, these measures are not always used,24 and mental health issues remain undertreated.25 26

Psychosocial challenges (eg, unemployment, interpersonal difficulties) develop because of physical, cognitive, or mental health symptoms. Seventy-one percent to 85% of those with progressive MS and 46% to 66% of those with relapsing-remitting MS are unemployed.27 28 Severe disability and cognitive impairment predict loss of employment, decline in living standards, and activity withdrawal.29 Patients with comorbidities have a greater likelihood of low income and change of relationship status.30 No psychometric instruments target psychosocial concerns, but conversation can. Given that aspects of HRQOL predict disability over time, addressing concerns could affect disease outcome.31

Cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial concerns may not be addressed in routine care2 4 14 21 25 (standard-of-care, regularly scheduled neurology appointments). The Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) recommends32 that all people with MS have access to collaborative, interdisciplinary care providing information, advice, and counseling and promoting wellness-focused activities. The CMSC recommends assessing all people with MS to determine HRQOL, social supports, financial resources, and cognitive, emotional, and educational needs to inform a comprehensive care plan. To our knowledge, only two studies examine how these issues are addressed in routine care. In a survey of CMSC member health professionals, 93% reported routinely assessing for depression, and half reported offering treatment.24 Most surveyed members reported asking a general question about depression, and 38% reported using a validated measure. Less than 4% of invitees completed this survey, so these numbers do not reflect the typical MS center. In an earlier survey,33 49% of CMSC practitioners did not use formal cognitive assessment and instead relied on observation of overt signs of cognitive impairment, which is known to be inadequate.14 No survey looked at psychosocial concerns. Surveys relied on retrospective estimates, which may be inaccurate. We undertook a medical record review of patients followed at the Ottawa Hospital MS Clinic with the goal of answering the following questions: 1) What proportion of people with MS in the clinic present with cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial concerns? 2) When concerns are identified, what proportion of cases receive a referral to associated services offered? 3) Do people with cognitive/mental health/psychosocial concerns access MS clinic services more often than those without?

Methods

Approval for the study was provided by the Ottawa Health Sciences Network Research Ethics Board. One hundred randomly selected medical records documenting at least one visit to the Ottawa Hospital MS Clinic from July 1, 2015, to June 30, 2016, were reviewed. Approximately 3000 medical records were assigned a unique number; 100 were randomly selected using computer-generated pseudorandom numbers. The first 100 eligible and accessible medical records were included.

Paper and electronic records yielded demographic data, disease characteristics, visit records, communication between patients and staff, treatment history, and information on identification, assessment, and treatment of cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial concerns. Visit notes contained documentation of subjective concerns (eg, difficulty concentrating at work) and recommended treatments. One reviewer categorized each concern as being related to mental health (ie, complaints of anxiety, depression, or irritability), cognition (ie, difficulties with attention, memory), or psychosocial issues (ie, difficulties related to relationships, finances, or work). Neither fatigue nor insomnia was counted. Because of the potential for use as treatment for pain, etc, a record of antidepressant medication use was not counted as evidence of a concern.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) was used to calculate descriptive statistics on demographic data and number of clinic contacts. Frequencies were calculated regarding proportion of people with MS with concerns, source/nature of concerns, and rate/nature of services/treatments offered. Nonparametric independent-samples tests determined whether demographic factors affected offer of treatment. Independent-samples Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare the mean age of patients with concerns who received a treatment offer or not. For other demographics, independent-samples χ2 tests were used to compare frequencies. To determine whether people with MS with identified concerns access clinic services more often than those without, independent-samples Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare the mean number of clinic contacts.

Results

Of the 100 randomly selected medical records, 66% were for female patients; mean ± SD age was 48.68 ± 12.45 years; and 55 had relapsing-remitting MS, 17 had secondary progressive MS, 8 had primary progressive MS, and 20 had other or subtype not indicated. The mean ± SD time since diagnosis was 12.46 ± 9.74 years; the mean ± SD Expanded Disability Status Scale score was 2.68 ± 2.25. See Table 1 for additional patient characteristics. One hundred patients had 142 visits and 89 phone/e-mail contacts (231 total contacts).

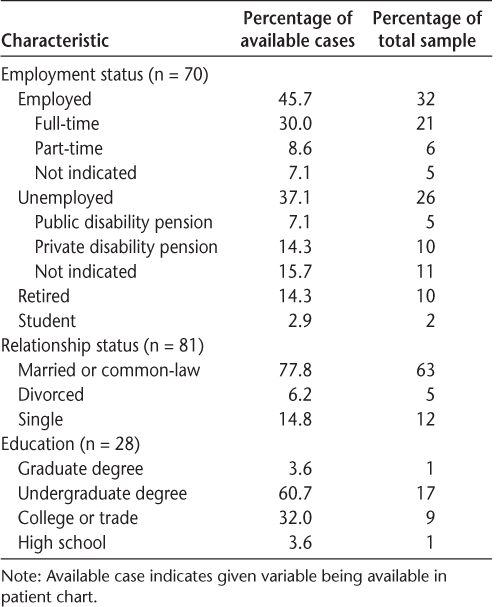

Patient characteristics reported for available cases and for total sample of 100

Twenty-five percent of patients had at least one subjective cognitive, mental health, or psychosocial concern. Of these patients, 48% experienced one, 32% two, and 20% three types. Disease duration (ie, time since diagnosis) or disability level did not influence whether concerns were identified.

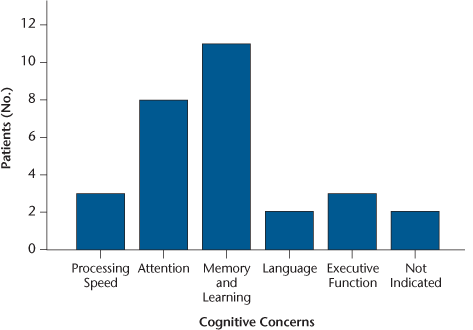

Seventeen percent of patients presented with at least one cognitive concern (Figure 1), which is significantly less than the expected 40% prevalence in people with MS.4 34 35 There was no record of any validated cognitive screening. Four patients underwent previous neuropsychological testing.

Frequencies of cognitive concerns by type

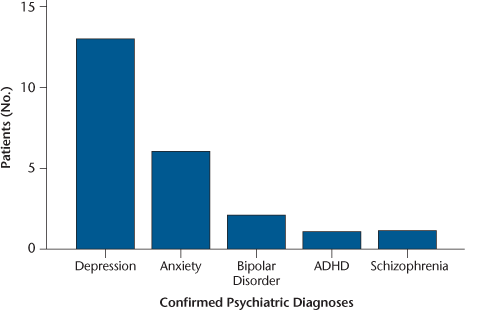

Fifteen percent of patients reported a mental health concern; 15% had at least one psychiatric diagnosis (Figure 2). This rate is significantly less than the expected 50% prevalence in people with MS (χ2 = 49.00, P < .001).36

Frequencies of confirmed psychiatric diagnoses

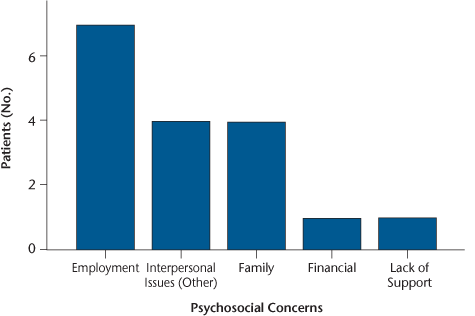

Eleven percent of participants reported at least one psychosocial concern (Figure 3). Although numbers vary when estimating rates of unemployment (46%–85%)27 28 and change of relationship status (7%–33%),27 28 current rates of psychosocial concerns were lower than expected.

Frequencies of psychosocial concerns by type

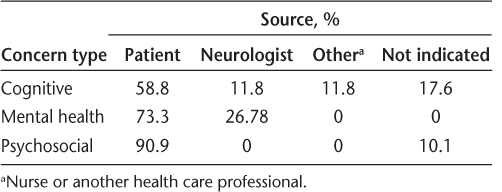

People with MS were more likely than neurologists to bring up nonphysical concerns (Table 2). Neurologists were more likely to raise mental health concerns than cognitive concerns. There was no indication that neurologists raised psychosocial concerns.

Sources of concerns raised during multiple sclerosis clinic routine visits

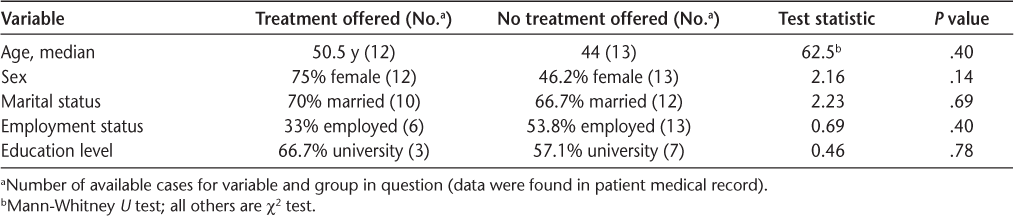

Of the 25 people with MS with at least one concern, treatment was suggested for 13 (52%): three of 17 for cognitive, nine of 15 for mental health, and three of 11 for psychosocial concerns. No evidence of referrals to services was found. The most common treatment offered was antidepressant agents (30.8%), then counseling (23.1%) and follow-up with the family doctor (23.1%). Follow-up with psychiatry (15.4%) or community-based support (eg, the MS Society) (7.7%) was also recommended. Demographic factors did not influence whether treatment was offered (Table 3).

Comparison of demographic variables for patients with multiple sclerosis offered versus not offered treatment when presenting with a cognitive, mental health, or psychosocial concern

Patients with one or more concerns (median contacts, 2.0) accessed MS clinic services significantly more often than did patients without concerns (median contacts, 1.0 [U = 647.5, P = .011]).

Discussion

Based on a review of 100 randomly selected medical records in our MS clinic, approximately one-quarter of the medical records documented at least one cognitive, mental health, or psychosocial concern—significantly fewer than expected. There was little evidence of validated assessments for cognitive or mental health concerns, and only half of the patients were offered treatment. These findings suggest that current practices are not adequately addressing important issues, and many patients are not receiving optimal care.

People with MS are likely experiencing concerns near expected rates, but issues are not identified. The discrepancy between reported and expected frequencies may be due to overreliance on self-disclosure. No evidence suggested that staff used screening measures. Reliance on patients to disclose can prevent identification of cognitive impairment because self-report is not an appropriate way of assessing cognitive function. People are often inaccurate at predicting their cognition (eg, anosognosia, mood).37 38 People with MS may remain silent due to stigma,39 especially those with mental health or psychosocial concerns,40 who may choose not to disclose.41 They may also think that such concerns are not relevant or may not see how issues affect symptoms. Barriers lengthen the time that mental health concerns go untreated, which is associated with a negative prognosis.39 Validated screening tools should be adopted to better identify cognitive9 42 and mental health concerns.22 23

The low identification rate may be because clinicians elect not to assess concerns, as has been reported anecdotally by clinic staff. They may not feel qualified to treat issues or may not be familiar with service navigation (particularly when social workers are not available, as was the case during review), or barriers to treatment access such as policies and cost may exist.3

For patients ineligible for subsidized services, private services are typically available. However, cost is often a barrier. The patients with MS in our study were more likely to be offered treatment for mental health concerns compared with cognitive concerns, possibly due to familiarity or availability of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy compared with occupational therapy and cognitive rehabilitation. Few patients had previous neuropsychological testing, which can be costly. Clinic staff may not be aware of patient issues and current treatments without communications from community-based health professionals. This review did not yield evidence of outside care. Possibly, some patients had concerns addressed outside the MS clinic, without effective communication of this. Although several patients were recommended to access community psychologists, there was no evidence that this was pursued. Providing referrals could increase adherence, communicate treatment importance, and facilitate interprofessional communication.

Ideally, an interdisciplinary team32 could be established to further reduce barriers. The CMSC notes that this team consists of various professionals (neurologists, other specialized physicians, nurses, social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, neuropsychologists, etc).32 Interdisciplinary services reduce demand on overburdened neurologists and nurses.32 Such a care team is efficacious in other areas (eg, chronic pain,43 stroke,44 Parkinson disease45), improving care and quality of life for patients and families.45 Interdisciplinary MS care centers are more likely to use validated screening measures and offer treatment for psychological concerns.24

Patients with MS with at least one concern accessed clinic services at almost double the rate of those without concerns, perhaps because they are attempting unsuccessfully to have needs met. The cost of psychotherapy can be less than that of pharmacotherapy or the absence of psychological treatment—by reducing visits, reducing need for pharmacotherapy, improving outcomes, and reducing disability-related expenses.46 47

Research-to-practice gaps exist due to external, organizational, and individual factors (eg, lack of funding, political will, or administrative resources; lack of communication between researchers and clinicians; lack of staff support).48 49 Clinicians may underestimate the impact of cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial issues compared with physical symptoms,1 50 and the introduction of new policies can be a complex process, requiring significant commitment and allocation of scarce resources.49

Study limitations include the inability to determine whether concerns were clinically significant. Because formal assessments were not performed, identification does not reflect diagnostic standards. However, including subjective concerns correctly reflected the practice of MS clinic staff in determining which patients might warrant attention and reflects the widespread practice of not using validated measures.24 33 Regardless, this approach produced far fewer concerns than expected in the literature, which supports the observation that concerns are being underidentified in routine care. Rates of cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial concerns may have been greater with a longer review period. Finally, data may have been richer had a larger sample of medical records been reviewed and more sites included. Future research could review larger samples to determine whether demographic factors influence identification and treatment rates, and multiple centers could be reviewed for greater generalizability and for assessing whether care improves after adoption of the interdisciplinary model.

The present study provides an objective look at current research-to-practice gaps in this center regarding people with MS who had cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial concerns. Solutions to this gap include adopting validated screening measures and increasing communication between providers. The ideal scenario is an interdisciplinary model of care as recommended by best practice guidelines.32

PRACTICE POINTS

Cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial concerns are highly prevalent in people with MS and have a significant effect on autonomy, well-being, and disease outcomes.

A variety of tools can quickly and easily identify these concerns in standard practice, but these may be underused, leading to issues not being adequately identified or addressed during routine MS care visits.

Research-to-practice gaps can be addressed by using screening tools, adopting an interdisciplinary model of care, and improving communication between people with MS and their care providers.

Financial Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Rothwell PM, McDowell Z, Wong CK, Dorman PJ. Doctors and patients don't agree: cross sectional study of patients' and doctors' perceptions and assessments of disability in multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 1997;314:1580–1583.

Mitchell AJ, Benito-Leon J, Gonzalez JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:556–566.

Rieckmann P, Centonze D, Elovaara I, et al. Unmet needs, burden of treatment, and patient engagement in multiple sclerosis: a combined perspective from the MS in the 21st Century Steering Group. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;19:153–160.

Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1139–1151.

Hughes AJ, Hartoonian N, Parmenter B, et al. Cognitive impairment and community integration outcomes in individuals living with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1973–1979.

Rao SM, Leo GJ, Ellington L, Nauertz T, Bernardin L, Unveragt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis, II: impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology. 1991;41:692–696.

Saccà F, Costabile T, Carotenuto A, et al. The EDSS integration with the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis and orientation tests. Mult Scler. 2017;23:1289–1296.

Benedict RHB, Amato MP, Boringa J, et al. Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS (BICAMS): international standards for validation. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:1–8.

Walker LA, Osman L, Berard JA, et al. Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS): Canadian contribution to the international validation project. J Neurol Sci. 2016;362:147–152.

Eshaghi A, Riyahi-Alam S, Roostaei T, et al. Validity and reliability of a Persian translation of the Minimal Assessment of Cognitive Function in Multiple Sclerosis (MACFIMS). Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;26:975–984.

Dusankova JB, Kalincik T, Havrdova E, Benedict RHB. Cross cultural validation of the Minimal Assessment of Cognitive Fuction in Multiple Sclerosis (MACFIMS) and the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS). Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;26:1186–1200.

Goretti B, Niccolai C, Hakiki B, et al. The Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS): normative values with gender, age and education corrections in the Italian population. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:1–6.

O'Connell K, Langdon D, Tubridy N, Hutchinson M, McGuigan C. A preliminary validation of the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS) tool in an Irish population with multiple sclerosis (MS). Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4:521–525.

Benedict RH. Integrating cognitive function screening and assessment into the routine care of multiple sclerosis patients. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:384–391.

Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Allen J, et al. Depression and multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;46:628–632.

Feinstein A. Multiple sclerosis and depression. Mult Scler. 2011;17:1276–1281.

Feinstein A. The Clinical Neuropsychiatry of Multiple Sclerosis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Hanna J, Feinstein A, Morrow SA. The association of pathological laughing and crying and cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2016;361:200–203.

Haussleiter IS, Brune M, Juckel G. Psychopathology in multiple sclerosis: diagnosis, prevalence and treatment. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2009;2:13–29.

Kosmidis MH, Giannakou M, Messinis L, Papathanasopoulos P. Psychotic features associated with multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22:55–66.

Skokou M, Soubasi E, Gourzis P. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review of assessment and treatment approaches in adult and pediatric populations. ISRN Neurol. 2012;2012:427102.

Honarmand K, Feinstein A. Validation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for use with multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2009;15:1518–1524.

Patten SB, Burton JM, Fiest KM, et al. Validity of four screening scales for major depression in MS. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1064–1071.

Gromisch ES, Schairer LC, Pasternak E, Kim SH, Foley FW. Assessment and treatment of psychiatric distress, sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, and pain in multiple sclerosis: a survey of members of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. Int J MS Care. 2016;18:291–297.

Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Vollmer T. The burden of mental comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: frequent, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Mult Scler. 2009;15:385–392.

McGuigan C, Hutchinson M. Unrecognised symptoms of depression in a community-based population with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2006;253:219–223.

Morales-Gonzales JM, Benito-Leon J, Rivera-Navarro J, Mitchell AJ; GEDMA Study Group. A systematic approach to analyse health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the GEDMA study. Mult Scler. 2004;10:47–54.

Cecile A, Janssens JW. Divorce and unemployment in multiple sclerosis: recalculation of the data of Morales-Gonzales JM, Benito-Leon J, Rivera-Navarro J and Mitchell AJ. Mult Scler. 2004;10:716.

Hakim EA, Bakheit AMO, Bryant TN, et al. The social impact of multiple sclerosis: a study of 305 patients and their relatives. Disabil Rehabil. 2000;22:288–293.

Thormann A, Sorensen PS, Koch-Henriksen N, Thygesen LC, Laursen B, Magyari M. Chronic comorbidity in multiple sclerosis is associated with lower incomes and dissolved intimate relationships. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:825–834.

Visschedijk MA, Uitdehaag BM, Klein M, et al. Value of health-related quality of life to predict disability course in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63:2046–2050.

Harris C, Costello K, Halper J, et al. Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers recommendations for care of those affected by multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2003;5:67–78.

Foley FW, Benedict RHB, Gromisch ES, DeLuca J. The need for screening, assessment, and treatment for cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: results of a multidisciplinary CMSC consensus conference, September 24, 2010. Int J MS Care. 2012;14:58–64.

Rao SM, Leo G, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: frequency, patterns, and predictions. Neurology. 1991;41:685–691.

Strober LB, Rao SM, Lee JC, Fischer E, Rudick R. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: an 18 year follow-up study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3:473–481.

Wood B, van der Mei IA, Ponsonby AL, et al. Prevalence and concurrence of anxiety, depression and fatigue over time in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19:217–224.

Middleton LS, Denney DR, Lynch SG, Parmenter B. The relationship between perceived and objective cognitive functioning in multiple sclerosis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;21:487–494.

Benedict RHB, Munschauer F, Linn R, et al. Screening for multiple sclerosis cognitive impairment using a self-administered 15-item questionnaire. Mult Scler. 2003;9:95–101.

Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45:11–27.

Anagnostouli M, Katsavos S, Artemiadis A, et al. Determinants of stigma in a cohort of Hellenic patients suffering from multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:101.

Grytten N, Måseide P. “What is expressed is not always what is felt”: coping with stigma and the embodiment of perceived illegitimacy of multiple sclerosis. Chronic Illn. 2005;1:231–243.

Langdon DW, Amato MP, Boringa J, et al. Recommendations for a Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS). Mult Scler. 2012;18:891–898.

Seal K, Becker W, Tighe J, Li Y, Rife T. Managing chronic pain in primary care: it really does take a village. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:931–934.

Summers D, Leonard A, Wentworth D, et al. Comprehensive overview of nursing and interdisciplinary care of the acute ischemic stroke patient: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40:2911–2944.

Giladi N, Manor Y, Hilel A, Gurevich T. Interdisciplinary teamwork for the treatment of people with Parkinson's disease and their families. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14:493.

Hunsley J. The Cost-effectiveness of Psychological Interventions. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Psychological Association; 2002.

Chiles JA, Lambert MJ, Hatch AL. The impact of psychological interventions on medical cost offset: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1999;6:204–220.

Mallonee S, Fowler C, Istre GR. Bridging the gap between research and practice: a continuing challenge. Injury Prev. 2006;12:357–359.

Gotham HJ. Advancing the implementation of evidence-based practices into clinical practice: how do we get there from here? Prof Psychol Res Prac. 2006;37:606–613.

Nortvedt MW, Riise T, Myhr KM, Nyland HI. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: measuring the disease effects more broadly. Neurology. 1999;53:1098–1103.