Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Development and Preliminary Evaluation of a 3-Week Inpatient Energy Management Education Program for People with Multiple Sclerosis–Related Fatigue

Abstract

Background:

Energy conservation strategies and cognitive behavioral therapy techniques are valid parts of outpatient fatigue management education in people with multiple sclerosis (MS). In many European countries, multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people with MS is chiefly delivered in specialized rehabilitation centers, where they benefit from short intensive inpatient rehabilitation annually. However, no evidence-based and standardized fatigue management education program compatible with the inpatient setting is available.

Methods:

Based on a literature search and the expertise of occupational therapists (OTs), a manualized group-based Inpatient Energy Management Education (IEME) program for use during 3-week inpatient rehabilitation that incorporates energy conservation and cognitive behavioral management approaches was developed. An IEME pilot program operated by trained OTs included 13 people with MS-related fatigue. The experiences of the IEME users and OTs were collected during focus groups to refine the program's materials and verify its feasibility in the inpatient setting.

Results:

The program was feasible in an inpatient setting and met the needs of the people with MS. Targeted behaviors were taught to all participants in a clinical context. In-charge OTs were able to effect behavioral change through IEME.

Conclusions:

Users evaluated the evidence-based IEME program positively. The topics, supporting materials, and self-training tasks are useful for the promotion and facilitation of behavioral change. The next step is a clinical trial to investigate the efficacy of IEME and to evaluate relevant changes in self-efficacy, fatigue impact, and quality of life after patients return home.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory demyelinating and degenerative disease of the central nervous system that is considered one of the most frequent causes of disability in young adults.1 Fatigue is a common symptom for people with MS, affecting almost 90% of this population. Furthermore, two-thirds of people with MS describe fatigue as their most disturbing symptom.2 The Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines declared in a multidisciplinary consensus definition that fatigue is “a subjective lack of physical and/or mental energy that is perceived by the individual or caregiver to interfere with usual and desired activities.”3(p2) Primary fatigue refers to fatigue in the absence of an apparent cause and is specific to MS, whereas secondary fatigue is a consequence of other concomitant conditions (eg, psychological disturbances, musculoskeletal problems, sleep disorders, or medication adverse effects) that may be related to MS as well as to other diseases.4 The pathophysiology of primary fatigue in MS is highly complex and, so far, not completely understood.5 Fatigue related to MS limits participation in everyday activities6 and has a major effect on quality of life, affecting productivity and employment.7

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines8 recommend a multidisciplinary approach for the management of fatigue that involves exercise therapy, self-management, and education concurrent with medication therapy. To date pharmacologic treatments do not produce desired effects, whereas rehabilitation strategies provide a better effect and are first-line treatments.9 Two meta-analyses9 10 provide moderate-to-strong evidence that fatigue management education affects the impact fatigue has on occupational performance and quality of life. These treatment protocols11–14 are based on work by Packer et al15 and integrate both energy conservation strategies and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques, taking place in outpatient group settings with 6 to 12 peer participants. Six sessions (±2 hours per week, ±12 hours total) follow a hierarchical order and support the development of activity patterns to reduce fatigue through a methodical analysis of working tasks and household and leisure activities in all relevant settings. To support the acquisition of new skills and the formulation of new behavior goals, an occupational therapist (OT) provides information and stimulates discussion and exchange between course participants through guiding questions and activity involvement. Homework assignments are used to apply energy conservation strategies and to implement behavioral change.

In Switzerland and other European countries, multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people with MS is widely used in specialized rehabilitation centers. People with MS benefit from intensive inpatient rehabilitation (2–4 weeks) annually, but there is still a lack of evidence that traditional multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation can significantly improve fatigue management in people with MS.16 During the rest of the year, people with MS maintain their normal lifestyle, which includes job, family life, and social and leisure activities. Some patients receive physiotherapy, but currently no specialized fatigue management is offered. Outpatient protocols are different from typical multidisciplinary and intensive inpatient rehabilitation. Hence, there is a barrier to the transfer of knowledge. Other barriers are the lack of trained OTs, organizational constraints of rehabilitation centers, and the need for culturally appropriate translation of relevant educational materials. Centers that regularly treat people with MS have a need for a standardized and evidence-based fatigue education program compatible with an inpatient setting that maintains the principal components of the outpatient program (eg, main topics, reinforcing effect of peers, principals of patient education, empowerment, and change management).

To adapt fatigue management education from an outpatient to an inpatient setting, four conditions must be met. 1) The duration must be reduced from 6 to 3 weeks, with increased frequency. 2) It must be feasible with a dynamic group composition in that continuous enrollment and discharge of people with MS may occur on any day of the week. 3) Self-training tasks must be redesigned because patient activities are different during rehabilitation. 4) Learned lessons and target behaviors must be transferred from the clinic to the home setting.

The first aim of this study was to develop a group-based Inpatient Energy Management Education (IEME) program for people with MS-related fatigue based on current evidence. The second aim was to complete a pilot program with 10 to 15 people with MS to evaluate OT and participant experiences.

Methods

Design

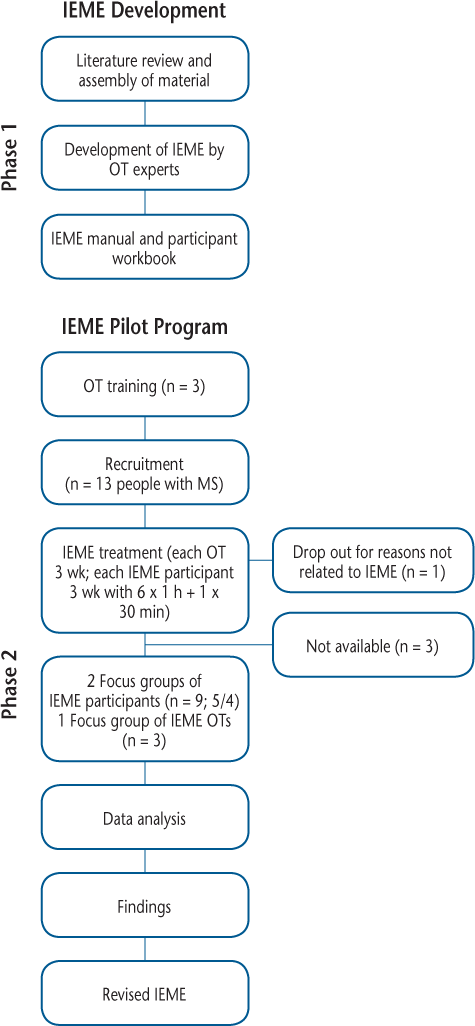

A qualitative research method based on focus group discussions was used.17 The study flowchart in Figure 1 shows the development and the pilot program phase. Ethical approval was obtained from the local research ethics committee (Ethikkommission Ostschweiz). The study was prospectively registered (German Clinical Trials Register at drks.de; ID: DRKS00011634).

Study flowchart

Phase 1: Development of the IEME Program

Literature Review and Assembly of Materials

The aims were as follows. 1) Obtain overview knowledge of clinical trials that included energy conservation strategies, CBT approaches, and fatigue management education interventions for people with MS-related fatigue. 2) Identify user evaluation studies of fatigue management education. 3) Prepare manuals of fatigue management education protocols and materials appropriate for people with MS. We searched MEDLINE, Embase (Ovid), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL [EBSCO]), peer-reviewed reviews18 and meta-analyses updated to 2014,9 10 and clinical studies from 2014 to 2016.19 20 Search terms included multiple sclerosis, fatigue management education, energy conservation, cognitive behavioral therapy, self-management, randomized clinical trials, efficacy, effectiveness, and user experience. Intervention settings, topics, work materials, and intervention techniques were extracted from selected studies. Authors and experts in the field were contacted directly for more detailed information about intervention content and techniques. Actual practice guidelines,8 21 books,22 23 websites from national and international OT and MS associations,24 and information booklets about fatigue management education were consulted. Two of us (R.H. and A.W.) reviewed the collected materials and classified them by strength of evidence,25 topic, relevance, and affinity with the principles of patient education, empowerment, behavioral change focus, human occupation, and energy conservation.

Development of Intervention by OT Experts

Two OT experts (R.H. and A.W.) with 15 years of experience in neurorehabilitation and MS care in both inpatient and outpatient settings led the intervention development. Representative intervention protocols for energy conservation strategies15 26 and CBT approaches20 27 identified in the literature were used for development of the IEME program. Recommendations in published studies for intervention evaluation and user experience assessment28–30 were considered and included where applicable. The process during the development stage was a circular process, contaminated by the exchange of experiences and the integration of knowledge accumulated during the literature review.

IEME Manual and Participant Workbook

Integrated knowledge and materials from the literature review along with the expertise of two of us (R.H. and A.W.) were used in creating the IEME OT manual and the participant workbook. The IEME program incorporates the typical features of fatigue management education derived from previous studies, including 1) group interventions, 2) topics and content, 3) self-learning tasks between lessons, and 4) individual goal setting and the integration of recommendations. During editing of the IEME materials, didactic principles for adult education,31 principles of patient education,32 user-friendliness, and practical aspects were considered.

Phase 2: IEME Pilot Program

Training for OTs

After completion of the IEME manual and workbook, three OTs from the Rehabilitation Centre Valens (Valens, Switzerland) were chosen for the IEME introduction day and the pilot program. The selection was purposefully heterogeneous (maximum variety sampling) regarding aspects such as age, work experience, educational level, and country of education. Two of us (R.H. and A.W.) taught the course together. The purpose was to transmit the underlying concepts and to provide the OTs with the opportunity to simulate activities, role-play, and increase their skills in group management and moderation. Direct OT feedback and critical reflections about content, clarity, and teaching methods were noted when training was complete. These notes were considered for development of the focus group interview guidelines for the IEME pilot program participants and the OTs.

Setting and Participants

The aim was to include 10 to 15 people with MS in a 9-week pilot program to guarantee that every OT and participant completed the education program at least once. The Rehabilitation Centre Valens is specialized in neurologic rehabilitation, and approximately 400 inpatients with MS are treated every year. People with MS who were on the waiting list for a 3-week rehabilitation at the center from March until May 2017 and who fulfilled the inclusion criteria (>18 years of age, confirmed diagnosis of MS according to the McDonald criteria,33 Fatigue Severity Scale34 score ≥4, and Expanded Disability Status Scale35 score ≤6.5) were informed by mail about the study. A few days before admission they were contacted by phone to verify additional inclusion criteria (literacy in German, agreement to attend the IEME lessons during rehabilitation) and exclusion criteria (telephone Mini-Mental Status Examination36 score <21, Beck Depression Inventory–fast screening37 score >4) and to answer any questions. Thirteen people with MS were recruited for the IEME pilot program. Informed consent was provided by each.

IEME and Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation

People with MS participated in six IEME lessons, each lasting 1 hour. The IEME was part of the multidisciplinary rehabilitation program in the center, which is a combination of 2- to 3-hour therapeutic interventions per day in individual and group settings. This individualized and goal-oriented program included physiotherapy (endurance and reinforcement training), occupational therapy (ability and adaptation training), speech therapy, neuropsychological training, and medical and social counseling as needed. At the end of the 9-week pilot program, 12 IEME participants completed the program. One person dropped out after two lessons for administrative reasons unrelated to IEME (Figure 1).

Focus Groups

The methodological approach chosen for the focus groups was based on that of Krüger and Casey,17 with R.H. in the role of moderator and A.W. participating as co-moderator. The interview guideline for people with MS focused on IEME content and comprehensibility, organization, behavioral change, group as intervention format, and possible improvements; with the OTs, the IEME training day was also discussed. For the focus groups with IEME participants, two dates were purposefully chosen to grantee a maximum of experience with IEME in a sample as large as possible. All IEME participants present in the center on these 2 days (five in April and four in May) agreed to participate in the group discussions. The participants knew that R.H. and A.W. had developed the IEME. The focus group with the three IEME OTs took place at the end of the pilot program (May). At the first IEME session, people with MS and OTs were asked to take notes in their manual whenever they found something disturbing, irrelevant, or improbable. Focus group participants were asked to consider their notes before the start of the discussion. The OTs kept record sheets during the training and the IEME pilot program. The interview guidelines for the focus groups were devised to collect participant and OT suggestions for improvements of IEME. The three focus groups took place at the center in a quiet meeting room without the presence of nonparticipants or disturbances. All the group interviews were audio recorded. As co-moderator, A.W. took field notes that summarized the main arguments at the end of every discussion. R.H. and A.W. had a debriefing immediately after each focus group. The first participant group discussion lasted nearly 60 minutes, and the OT group discussion a few minutes more. The second participant group discussion lasted just longer than 50 minutes.

Data Analysis

The focus groups (two for IEME participants and one for IEME OTs) were transcribed verbatim based on the audio recordings. In addition to the transcript, the co-moderator's notes, the member check summaries, and the debriefing notes were part of the analysis process. A content analysis was performed using open and axial coding to explore and systematically organize the data into a structured format.38

Results

Phase 1: IEME Development

The underlying concepts of IEME are the principles of patient education39 and empowerment,40 the transtheoretical model with its stages of change,41 self-efficacy theories,42 theoretical basis and specific knowledge of the OT discipline,21 43 44 and the techniques of behavior change.45 46

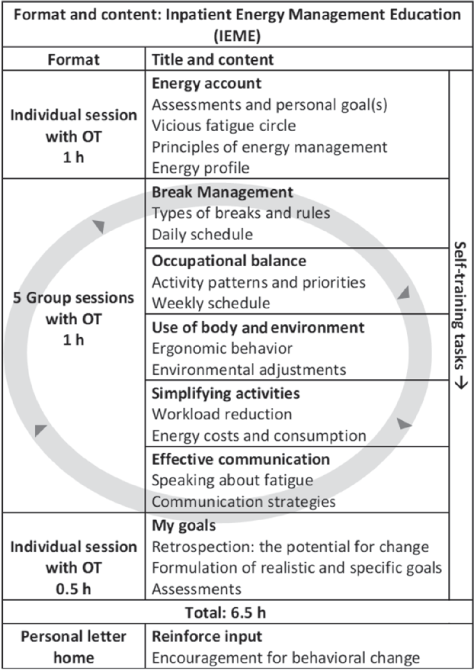

Format

The complete education program is 6.5 hours in duration and is conducted by a trained OT over a 3-week period. The IEME starts on the first day after admission with an individual lesson, followed by five 1-hour IEME group sessions delivered continuously on two fixed days per week, and concludes with an individual session (0.5 hour). The order in which an individual attends the group sessions is flexible because they are self-contained units. Between each lesson, participants are instructed to complete specific self-training assignments. Six weeks after returning home, participants receive a reinforcement in the form of a letter/e-mail.

Content and Materials

The content and structure of IEME are shown in Figure 2. The IEME treatment protocol is described in the manual, which consists of an introduction with relevant information about the underlying concepts of IEME as well as a detailed description of every session. The workbook for participants accompanies the program. It includes detailed information on all the topics, all worksheets for the lessons, and for the time after hospitalization both self-training and appropriate additional information. Each IEME lesson is deliberately structured such that all stages of change can be addressed and supported. Knowledge available in the group is shared during each session, but the focus is on reflection and exchange within the group, individual analysis and formulation of goals, and the acquisition of new skills. Self-training served as practice for new behavior patterns, which depend on the need and stage of the person, deepened reflection, and knowledge of specific topics. Based on the taxonomy of behavior change techniques,46 the IEME used primarily knowledge, social support, feedback, monitoring, behavior and outcome comparisons, goals and action planning, antecedents, self-belief, repetition, and substitution as techniques that supported behavior change in the participants.

Format and content of Inpatient Energy Management Education (IEME)

Phase 2: Pilot Program

IEME Treatment

Between March and June 2017, every OT guided every part of the IEME program at least once. In total, they completed 24 individual and 15 group sessions. Based on the record sheets, the OTs reported high treatment fidelity, with the completion of 83% of all described tasks in the manual.

Focus Group with IEME Participants

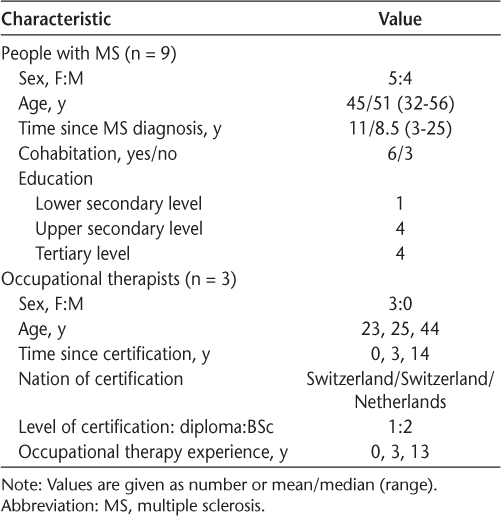

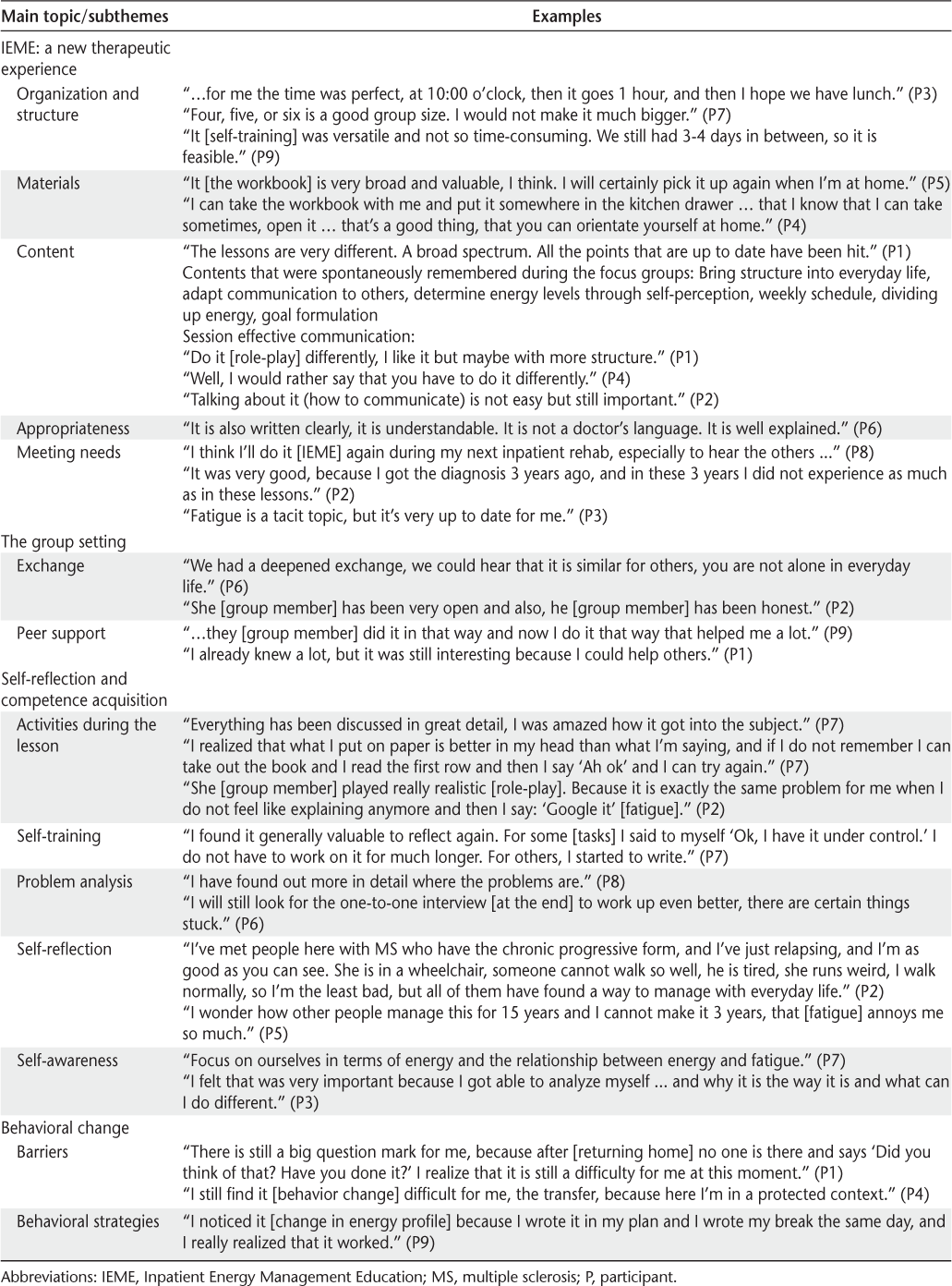

The IEME participants in the rehabilitation program were heterogeneous regarding age, sex, MS onset, and educational level (Table 1). Four main topics emerged from discussions. 1) IEME is described as a new therapeutic experience tailored to the needs of people with MS with related fatigue. The format and content are judged as an ideal framework for dealing with symptoms of fatigue, learning about effective behavioral strategies, and increasing a sense of personal control. Participants suggested that during the session “effective communication” and more structured guidance for role-playing would be useful. 2) The group setting, with its open exchange and peer support, was perceived as an important incentive that contributed to a more profound reflection on daily routines, reinforcing the use of energy conservation strategies. Even participants with many symptoms and educational experience found something valuable and were reassured in their approach and direction. 3) Self-reflection and competence acquisition as main goals of IEME were recognized as meaningful. The activities during the sessions and the self-training tasks allowed an in-depth individualized approach. 4) Behavioral change is the long-term goal of IEME. At the time of the focus groups, participants had positively experienced the effects of inpatient energy conservation strategies but had not experienced those in real-life situations. The confidence of the IEME participants in their capacity to transfer new knowledge and maintain behavioral change over time during their daily routine was unstable (Table 2).

Characteristics of focus group participants

Findings with illustrative quotations for the nine IEME focus group participants

Focus Group with IEME OTs

The three OTs who have been trained and have led the IEME pilot program were heterogeneous regarding age, OT practice, and experience in the care of people with MS (Table 1).

The discussion can be summarized in four main topics. 1) OT education day: The IEME-led training was rated positively and was appropriate for all OTs. Communication skills for group discussion management should be improved. Group training for fatigue management, the principles of patient education, and the stages of behavioral change were somewhat new to the OTs but were communicated well. All the OTs wanted more time during the introduction to practice skills, for example, group moderation. 2) The IEME format: The structure of the IEME program, with its self-contained units, could be easily integrated into an inpatient setting. The content and time frame of the sessions were realistic and feasible. All relevant aspects for handling symptoms were addressed and covered by group tasks and self-training. Group cohesiveness increased despite a constant change in member composition. 3) The role of OTs: Leading IEME requires a high level of mental presence, content knowledge, flexibility, and creativity. Depending on the group constellation, open exchange and deeper reflection are more or less easy to achieve. For all the OTs, the therapy sessions were a personal and professional enrichment. 4) Improvements needed: For the OTs, the IEME does not require any significant structural or substantive change. Only for the lesson “effective communication” was a different sequence suggested, and concrete recommendations were provided. Furthermore, ideas for minor optimizations could be collected, such as a clearer distinction between training tasks to perform during rehabilitation from those more related to transfer in the home setting. The OTs identified a need to share the principles of energy management with multidisciplinary teams to ensure coherent patient communication during rehabilitation.

Discussion

The IEME program was developed based on evidence-based literature. For that reason, the course addresses similar issues and is based on the same principles as outpatient programs. Nevertheless, note that IEME takes 6.5 hours instead of ±12 hours and is performed in a different context.

We trained three OTs in IEME execution and included 12 patients with MS with related fatigue in a pilot program. The user experience was positive, and the six sessions were feasible within a 3-week inpatient rehabilitation stay. The IEME was well received, and attendance was high. For some patients, it was the first time they had received specific information about fatigue management, whereas others had previous experiences with energy conservation information. All the participants highly valued peer interaction, the exchange of ideas, and deep reflection based on focus group transcripts. All the developed materials and tasks were easy to understand and were considered useful for the future. The IEME, with its circular frame, was integrated without problem into the regular rehabilitation program with no drastic structural or substantive changes.

The present findings are in line with data from outpatient courses, which reported similar user experiences and opinions despite the structural and contextual differences.28–30 Thanks to the reported critical aspects from outpatient programs28 47 (worksheets in disorder, unclear instructions, unfocused lessons), we were able to improve IEME during the development phase. Indeed, IEME participants emphasized their satisfaction with the well-structured workbook and the goal-oriented lessons. Another important difference between IEME and outpatient courses is that participants implement energy conservation strategies in an environment in which they do not have routines. This can be an advantage because they do not need to modify their habits and are freer to verify the potential effects of energy conservation strategies. In contrast, rehabilitation has a prefixed time schedule that is artificial and dissimilar to real life. For that reason, we created two types of self-training tasks. The first type refers to the inpatient environment with specific tasks that are easy to train (eg, ergonomic postures during sitting activities); the second type stimulates the participants to reflect on useful behavioral changes in their own life situations (eg, arrangement of activity stations). They are asked to formulate concrete plans and to imagine solutions.

Although positive experiences and empowerments were perceived with IEME, a preoccupation of IEME participants was their capacity to maintain and consolidate desired changes after returning home. Participants were concerned about their self-efficacy and their ability to overcome barriers during implementation. Hence, it was important to reduce their anxiety and provide support. Bandura42 suggested four ways to increase self-efficacy: 1) learn how to manage stress and anxiety when performing a new task, 2) experience success in overcoming obstacles, 3) observe peers being successful, and 4) be persuaded by others that you can perform a required task. The results of the focus groups confirm that IEME participants used successful energy conservation strategies during the self-task training. They shared their experiences at the beginning of every group session and received encouragement from peers and the OT. To reinforce the management of stress, OTs should refer repeatedly to the aim of the individual session and especially the importance of setting concrete and realistic goals. In addition, the challenge of transfer should be emphasized in the workbook, as well as the relationships among self-training, skills acquisition, and the facilitated transfer of energy conservation strategies. Visual cues in the workbook would help to identify those self-training tasks meant to facilitate the transfer of new skills and strategies into an everyday context. A digital version of the workbook with facilitated access, customizable outputs, and an energy profile application would be useful for future development (eg, assistive devices and audiobooks could reduce obstacles and increase self-efficacy). An internet platform that provides boosters and supplemental information would maintain and build a supportive community, which would support self-management and reduce concerns about implementation.48 49 One-to-one OT sessions after the return home would be useful for those still in a preparative stage of change, and they have been shown to be valuable.50

This study has shown that three OTs with different experience in MS care were able to execute IEME after 1 day of education. The manual is a practical and helpful instrument and supports OTs in their complex task of managing interactions and the needs of people with MS. They suggested an increase in typical situation simulations and the practice of moderating skills during the training day. Based on that, future OT education will be for 2 days, with more time to discuss underlying concepts such as self-efficacy, the transtheoretical model, and the practice of motivational interviewing.51

This study has some limitations. All the focus group participants and OTs were aware that the facilitators of the focus groups were also the IEME developers. However, the validity of results was supported by the provocative questions included in the interview guidelines, the field notes and comments from the focus groups, the completed workbooks, and the member check at the end of each focus group. Currently, we do not have data on the long-term effectiveness of the program. Because this was a pilot, the sample size of 12 participants and three OTs was small. The chosen method allowed gathering suggestions and exploring experiences but did not allow for conclusions regarding the strength of the intervention, modifying variables such as self-efficacy, or outcomes such as Modified Fatigue Impact Scale score.

The strengths of the IEME program are that it is based on previous studies and evidence-based treatment protocols, integrates actual knowledge from patient education, empowers participants, and changes behavior. It addresses people with MS-related fatigue during a short inpatient rehabilitation period and provides 6.5 hours in which to gain knowledge, acquire new skills, and receive support through intensive peer exchange. After the first session, participants trained targeted behaviors in a clinical context, and at the last session they formulated goals related to behavior change in daily life. Further research should verify the possible role and benefit of trained peers during IEME and after discharge,52 and the real effect of IEME on self-efficacy, fatigue, and quality of life should be assessed after return home. Efficacy should be compared with that of other management interventions in a randomized clinical trial.

In conclusion, this study has shown the feasibility of the IEME program in an inpatient setting and the value that participants attribute to peer exchange. The group intervention with peers is a powerful element in health promotion and is considered a key aspect in the self-management of people with chronic diseases.52 For this reason, health professionals and rehabilitation institutions should make an effort to guarantee patients the benefit of well-designed group therapies, even if this is an organizational challenge. Based on the findings of this study and the developed materials (OT training concept, manual, and workbook), it is possible for other rehabilitation centers to implement inpatient education for people with MS-related fatigue and to support an effective knowledge transfer into practice, making sure to share the principles of IEME with multidisciplinary teams to support behavioral change.

PRACTICE POINTS

We developed the Inpatient Energy Management Education (IEME) program for the management of MS fatigue during inpatient rehabilitation stays.

In a pilot study, the IEME program was feasible, participant satisfaction was high, and behavioral changes were reported.

Currently, no information about the efficacy of IEME after patients return home is available.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants involved in this study.

References

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–1517.

Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA, Marck CH, et al. Clinically significant fatigue: prevalence and associated factors in an international sample of adults with multiple sclerosis recruited via the internet. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0115541.

Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatigue and Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence-Based Management Strategies for Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

Rottoli M, La Gioia S, Frigeni B, Barcella V. Pathophysiology, assessment and management of multiple sclerosis fatigue: an update. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17:373–379.

Bogdan I, Cercinani M, Rashid W. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: why is it so difficult to manage? Adv Clin Neurosci Rehabil (ACNR). 2017;16:8–10.

Krupp L. Fatigue is intrinsic to multiple sclerosis (MS) and is the most commonly reported symptom of the disease. Mult Scler. 2006;12: 367–368.

Flensner G, Ek A-C, Landtblom A-M, Söderhamn O. Fatigue in relation to perceived health: people with multiple sclerosis compared with people in the general population. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22:391–400.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multiple sclerosis in adults: management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg186/chapter/1-recommendations. Published October 2014. Accessed October 27, 2017.

Asano M, Finlayson ML. Meta-analysis of three different types of fatigue management interventions for people with multiple sclerosis: exercise, education, and medication. Mult Scler Int. 2014;2014:1–12.

Blikman LJ, Huisstede BM, Kooijmans H, Stam HJ, Bussmann JB, van Meeteren J. Effectiveness of energy conservation treatment in reducing fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:1360–1376.

Mathiowetz V, Finlayson M, Matuska K, Chen HY, Luo P. Randomized controlled trial of an energy conservation course for persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:592–601.

Finlayson M, Preissner K, Cho C, Plow M. Randomized trial of a teleconference-delivered fatigue management program for people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2011;17:1130–1140.

Vanage SM, Gilbertson KK, Mathiowetz V. Effects of an energy conservation course on fatigue impact for persons with progressive multiple sclerosis. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57:315–323.

Thomas S, Thomas PW, Kersten P, et al. A pragmatic parallel arm multi-centre randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a group-based fatigue management programme (FACETS) for people with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:1092–1099.

Packer T, Brink N, Sauriol A. Managing Fatigue. Tucson, AZ: Therapy Skill Builders; 1995.

Khan F, Turner-Stokes L, Ng L, Kilpatrick T. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for adults with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD006036.

Krüger R, Casey M. Focus Group: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2015.

Yu C-H, Mathiowetz V. Systematic review of occupational therapy-related interventions for people with multiple sclerosis, part 2: impairment. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68:33–38.

Kos D, Duportail M, Meirte J, et al. The effectiveness of a self-management occupational therapy intervention on activity performance in individuals with multiple sclerosis-related fatigue: a randomized-controlled trial. Int J Rehabil Res. 2016;39:255–262.

Wendebourg MJ, Feddersen LK, Lau S, et al. Development and feasibility of an evidence-based patient education program for managing fatigue in multiple sclerosis: the “Fatigue Management in MS” program (FatiMa). Int J MS Care. 2016;18:129–137.

Preston J, Edmans J, eds. Occupational Therapy and Neurological Conditions. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2016.

Harrison S. Fatigue Management for People with Multiple Sclerosis. London, United Kingdom: College of Occupational Therapists; 2010.

Lorenzen H. Fatigue Management: Umgang mit chronischer Müdigkeit und Erschöpfung: Ein Ratgeber für Betroffene, Angehörige und Fachleute des Gesundheitswesens. 1. Aufl. Idstein, Germany: Schulz-Kirchner; 2010.

Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. MS in focus: fatigue und MS. https://www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/MS-in-focus-19-Fatigue-German.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed December 12, 2016.

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC, Hayward R, Cook DJ, Cook RJ; Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Users' guides to the medical literature, IX: a method for grading health care recommendations. JAMA. 1995;274:1800–1804.

Fox KJ. Fatigue Management in Chronic Illness: Implications for Use in a One-to-One Occupational Therapy Setting [doctoral project]. Chicago: University of Illinois–Chicago Department of Occupational Therapy; 2010.

Thomas S, Thomas PW, Nock A, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a cognitive behavioural approach to fatigue management in people with multiple sclerosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:240–249.

Mathiowetz V, Busch ML. Participant evaluation of energy conservation course for people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2006;8: 98–106.

Matuska K, Finlayson M. Use and perceived effectiveness of energy conservation strategies for managing multiple sclerosis fatigue. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:62–69.

Thomas S, Kersten P, Thomas PW, et al. Exploring strategies used following a group-based fatigue management programme for people with multiple sclerosis (FACETS) via the Fatigue Management Strategies Questionnaire (FMSQ). BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008274.

Merriam SB, Bierema LL. Adult Learning. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2013.

Pusic MV, Ching K, Yin HS, Kessler D. Seven practical principles for improving patient education: evidence-based ideas from cognition science. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:119–122.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302.

Valko PO, Bassetti CL, Bloch KE, Held U, Baumann CR. Validation of the fatigue severity scale in a Swiss cohort. Sleep. 2008;31: 1601–1607.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33: 1444–1452.

Newkirk LA, Kim JM, Thompson JM, Tinklenberg JR, Yesavage JA, Taylor JL. Validation of a 26-Point Telephone Version of the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17:81–87.

Neitzer A, Sun S, Doss S, Moran J, Schiller B. Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen (BDI-FS): an efficient tool for depression screening in patients with end-stage renal disease. Hemodial Int. 2012;16: 207–213.

Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2012.

Lorig KR, Halsted R, Holman MD. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7.

Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Van Hecke A. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:1923–1939.

Norcross JC, Krebs PM, Prochaska JO. Stages of change. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:143–154.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215.

Finlayson M. Occupational Therapy Practice and Research with Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 2003.

McColl MA, Law MC, Stewart D. Theoretical Basis of Occupational Therapy. 3rd ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Inc; 2015.

Michie S, Johnston M. Theories and techniques of behaviour change: developing a cumulative science of behaviour change. Health Psychol Rev. 2012;6:1–6.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95.

Holberg C, Finlayson M. Factors influencing the use of energy conservation strategies by persons with multiple sclerosis. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:96–107.

Caiata Zufferey M, Schulz PJ. Self-management of chronic low back pain: an exploration of the impact of a patient-centered website. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:27–32.

Pétrin J, Akbar N, Turpin K, Smyth P, Finlayson M. The experience of persons with multiple sclerosis using MS INFoRm: an interactive fatigue management resource. Qual Health Res. 2018;28:778–788.

Van Heest KNL, Mogush AR, Mathiowetz VG. Effects of a one-to-one fatigue management course for people with chronic conditions and fatigue. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71:7104100020p1–7104100020p9.

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

Embuldeniya G, Veinot P, Bell E, et al. The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: a qualitative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:3–12.