Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Relationship Between Expanded Health Belief Model Variables and Mammography Screening Adherence in Women with Multiple Sclerosis

People with disabilities often find it more difficult to access health-care services than the general population, further jeopardizing their health and well-being. The purpose of this descriptive pilot study was to explore the relationship between variables of the Expanded Health Belief Model (EHBM) and adherence to mammography screening in a sample of homebound women with MS after completion of a National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) intervention, known as the “Home-Based Health Maintenance Program for Women with MS,” that was conducted in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. The intervention was conducted in the patients' homes and included education of the women and their partners on risk factors for breast cancer and instruction in breast examination techniques. The patients were also helped to make appointments for mammograms. This study derived its sample from the intervention program and used data on adherence recorded by the NMSS. After completion of the intervention, telephone interviews were conducted with women who met the inclusion criteria (N = 11). Descriptive statistics indicate that adherence can be successfully described using variables of the EHBM, including perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, and self-efficacy. The instruments chosen for the research were well tolerated, useful, and efficient to administer and allowed for immediate assessment.

Approximately 229,000 women in the United States were expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer in 2012.1 Recommended screening methods for breast cancer include mammography, clinical breast examination, and breast self-examination. The American Cancer Society recommends annual mammography screening for women aged 40 years and older,1 although the US Preventive Task Force recently sparked controversy by recommending the first mammogram only at age 50, and screening every other year thereafter.2 It is undisputed that, regardless of its limitations, mammography is the single most effective method of early detection of cancer before the onset of physical symptoms. Although mammography adherence rates have increased in the last 10 years, the most recent data from the National Health Interview Survey revealed that 35% to 46% of women aged 40 and older have not had a mammogram in the last 2 years and that 60% have not had one in the last 12 months.3

Women with MS are much less likely to receive mammography screening for breast cancer than those without MS. According to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS), only 1.5% of women with MS aged 40 years and older receive mammograms in a given year.4 Barriers to screening in women with MS include problems with physical mobility and the cost of the procedure. Yet few interventions have been developed to increase adherence to mammography screening recommendations in women with MS.

Background

The probability that women will engage in early-detection health behaviors can be predicted from individual variables, such as barriers/benefits and demographic/sociopsychological factors including age and education.5 Susceptibility has been measured specifically in mammography behavior by risk in women with intentions to have a mammogram.6–9 In contrast, there is little documentation of severity alone in relation to predictors of mammography behavior except by Champion.10 11 Benefits and barriers have been clearly documented to be predictive of mammography screening adherence.12–14 Cues to action used in mammography adherence have been expressed specifically by physician recommendation.9 15

Because perceived benefits, barriers, and susceptibility have explained only about 40% of the variance in mammography behavior, accurate measurement of additional constructs such as self-efficacy is important.16 Self-efficacy measures the strength and generality of women's efficacy expectations in relation to mammography.17 Examination of an array of potential modifying factors has produced mixed results. Rutledge et al.5 measured age and education, finding that both accounted for variability, while Lee and Vogel18 found that higher education levels were associated with regular use of screening mammography. The evidence is clear that perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, cues to action, self-efficacy, and specific modifying factors increase adherence to recommended screening. On the other hand, barriers including cost, inconvenience, and lack of knowledge reduce adherence to mammography screening. In addition, there are unique factors that can affect mammography screening adherence in women with MS as compared with the general population. Clinical progression of MS may include physical impairment19 20 and change in mental status.21–23 In addition, depressive symptoms are common in this population, which may further undermine motivation for mammography screening.24–26

An NMSS Intervention Program

In 1999, the Allegheny District Chapter of the NMSS identified nearly 2000 people with MS living in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Of these, 1460 were women. Because 18% of all individuals with MS have significant disability related to neurologic impairments that restrict their ability to leave their homes, approximately 260 women with MS in Allegheny County were estimated to be homebound owing to significant impairment.4 The physical disabilities associated with MS cause women to be at higher risk for delayed diagnosis of other chronic diseases. As a means to assess and combat this risk, the NMSS established a program in Allegheny County called “Home-Based Health Maintenance Program for Women with MS.” The program was designed to provide underserved female MS patients with access to early-detection procedures related to breast health. The local NMSS chapter approached 250 homebound women aged 40 to 70 years for participation, consisting of those who had not received regular breast and gynecologic care as identified through an NMSS database. As part of the program, a nurse-midwife visited the women's homes and educated them and their partners about risk factors for breast cancer and provided instruction in breast examination techniques. Written material was provided to reinforce the teaching session. At the home visit, the nurse-midwife collected data on age, history of physician recommendation for mammography, history of mammograms, smoking behavior, and last clinical breast examination, pelvic examination, and Pap test. Patients were also screened with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Finally, the women were helped to make appointments for mammograms, with the program providing transportation to and from appointments, which were held at a wheelchair-accessible radiology center employing staff who were proficient in alternative positioning when required. The mammogram was scheduled within 1 month of the home visit. The NMSS covered the cost of the screening.

Study Conceptual Framework and Purpose

The conceptual framework of this study was the Expanded Health Belief Model (EHBM), which is one of the most widely used models for explaining change and maintenance of health behavior, as well as for development of health behavior interventions.27 The concepts of the original Health Belief Model have been gradually reformulated in the context of health-related behavior to include the assumptions that one has the desire to avoid illness or to get well (value) and a belief that a specific health action available to that person would prevent illness. Original concepts included perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and modifying variables. The model was later expanded to include self-efficacy.

The purpose of this descriptive pilot study was to explore the relationship between variables of the EHBM (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, self-efficacy, and modifying factors) and adherence to mammography screening in homebound women with MS residing in Allegheny County who had received the NMSS intervention.

Methods

This study used a descriptive design to examine mammography screening adherence in a sample of homebound women with MS. After the “Home-Bound Health Maintenance Program for Women with MS” intervention described above, we interviewed subjects by telephone and assessed them using a variety of measures.

Measures

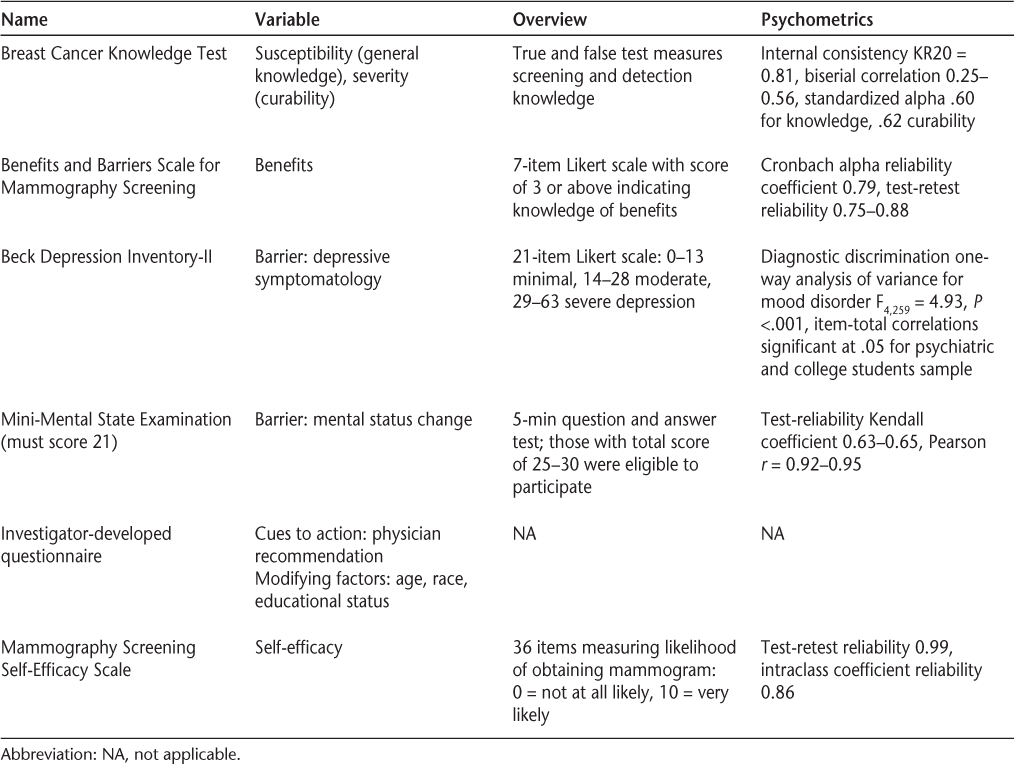

The following measures were used in this study: the Breast Cancer Knowledge Test (BCKT),28 the Benefits and Barriers Scale for Mammography Screening,29 the Beck Depression Inventory, second edition (BDI-II),30 the MMSE,31 an investigator-developed questionnaire, and the Mammography Screening Self-Efficacy Scale (MSSS)17 (Table 1).

Measures used in the study

Procedure

Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Review Board. The principal investigator (PI) obtained a list from the NMSS of Allegheny County of women participating in the NMSS program who expressed interest in receiving a call about this study. After conclusion of the intervention, the PI called potential subjects and explained the study. Written consent was obtained from those who were eligible for inclusion and agreed to participate. A time was mutually agreed upon for administration of the study instruments, which was done over the phone.

A total of 11 women met the inclusion criteria of the study and were interviewed by phone. All of the women completed the phone interview, with some using a speaker phone because they were unable to hold the receiver. The duration of the interview was 45 to 60 minutes. The target time used for obtaining a mammogram was within 2 months of receiving the NMSS intervention.

Findings

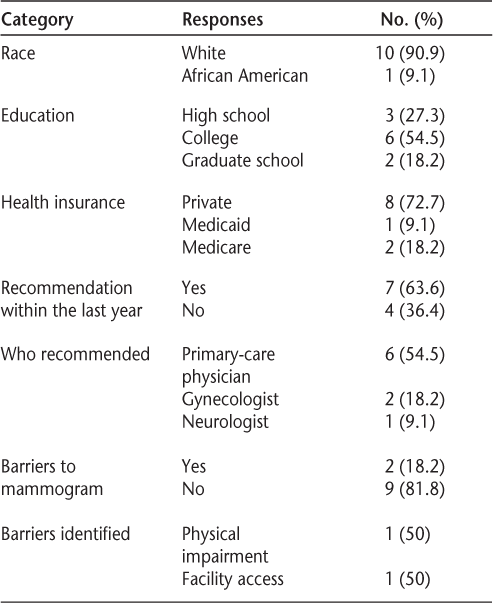

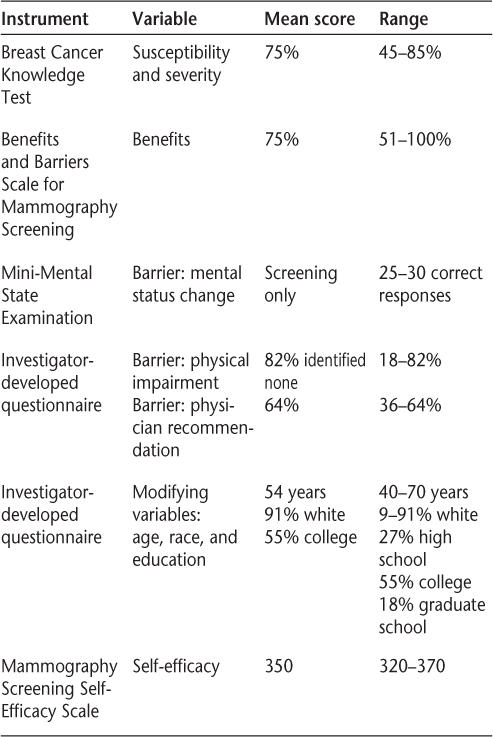

Demographic and other information on the study sample is summarized in Table 2. Data were obtained for 11 women. A total of 9 of the 11 women interviewed adhered to mammography screening. The mean score for the BCKT was 75%, with a range of 45% to 85% (Table 3). The Benefits and Barriers Scale for Mammography Screening had scores of 51% to 100%, with a mean score of 75%.

Demographic and other information on the study sample (N = 11)

Findings of the study

There were no difficulties with mental status, as all of the women qualified for the study by obtaining a score of at least 21 on the MMSE. The mean score on the BDI-II was 13, indicating minimal depression. The highest score was 28, or moderate depression. All the women had health insurance.

When questioned about physician recommendations for mammography, 64% of the women replied that screening had been recommended to them within the last year before receiving the NMSS intervention. Self-efficacy, which refers to the ability to obtain mammography screening in varying conditions, was measured using the MSSS, and it was found that all but one of the women planned to obtain a mammogram within the last year. Out of a possible 370 points, the mean score was 350. Cost was the main reason for not receiving a mammogram (unless all of the cost was covered, as for 10 of the women). Finally, in terms of modifying factors, the mean age was 56 years, the majority of participants (91%) were white, and all of the women were at least high school graduates.

Discussion

Previous findings regarding perceived susceptibility as a predictor of women's mammography-seeking behavior have been mixed. Rutledge et al.5 found risk/susceptibility to be among the common predictors of women's breast-health screening behaviors, while a study by Holm et al.14 contradicted this finding. Holm et al. also found that among women who participated in mammography screening, perceived seriousness or severity was not a significant predictor of mammography behavior. Along with other model variables, Champion10 found that adherence to mammography screening was influenced by perceived seriousness (or severity) of breast cancer, with women adherent to mammography screening guidelines having significantly higher scores on seriousness than those who were not adherent.11 Depressive symptomatology as measured by the BDI-II in the current study was minimal, with the highest score obtained indicating moderate depression. This was surprising given the NMSS's finding of a high rate of major depression in those with MS. However, it could not be determined whether the women in this study were receiving antidepressants.

In the present study, additional MS-related factors of cost, physical impairment, and mental status were not frequently identified as barriers to adherence to mammography screening, contrary to what would have been expected. The findings in the current study suggest that self-efficacy may also be related to mammography screening adherence in these women with MS. Matthews17 found that “prior preventive health practices, wellness orientation, and community resources explained variability in current overall adherence to preventive health practice.” In the current study, the community resource was the NMSS, which increased self-efficacy. Adherence was validated through the recording of an appointment kept at the mammography center for the actual mammogram in the NMSS database.

The women in this study were aged 40 to 70 years, and only 1 of the 11 women was black. Because family history data were not gathered, these demographic variables pertaining to familial tendencies toward breast cancer could not be specifically addressed. A prospective study completed previously found that regardless of race, age, and family history of breast cancer, women who believed that their susceptibility was high were less likely to adhere to screening guidelines than were women who believed that their susceptibility was moderate.6 Further differentiation could have taken place if the adherence data collection had occurred longitudinally with logistic regression analysis at the separate intervals of 1, 2, and 3 months instead of cross-sectionally at just the 2-month data-collection time point.

Results from this study indicate that interventions were successful in increasing knowledge and changing perceived susceptibility, benefits, and barriers in the right direction. The instruments chosen for the research were well tolerated, useful, and efficient to administer and allowed for immediate assessment. It is clear, however, that the relationship between EHBM variables and mammography screening adherence is complex, as evidenced by the conflicting findings in previous studies. Although methods of screening for breast cancer continue to evolve and improve, at present, high-quality mammography coupled with breast examination remains the most effective means of early detection. However, adherence to mammography screening in women with MS remains relatively low. Women who do not adhere to mammography screening also tend not to participate in the health-care system, perceive themselves as having relatively low susceptibility to breast cancer, and place relatively low value on mammography. The BDI-II, the Benefits and Barriers Scale for Mammography Screening, the BCKT, and the MSSS can be used successfully to assess homebound women with MS as part of a telephone interview. The sample used in this study had a high rate of adherence to mammography screening after the intervention, although it is recognized that the small size of the sample limits generalizability of the results.

Recommendations for Future Research

Future studies should be planned to permit examination of measurement psychometrics in this population. In addition, caregivers need to be incorporated in variable measurement in future studies, as they can contribute positively or negatively to health screening adherence by facilitating or impeding behaviors. Further studies should also explore other factors that may act as barriers to access to routine preventive health-care services such as mammograms for women with disabilities. Women with physical disabilities are at a higher risk for delayed diagnosis of breast cancer. Future research also should focus on subpopulations, such as women with disabilities who have low levels of education or income, or are members of a minority group, to rule out an interaction that may have occurred with other modifying factors. In addition, the NMSS intervention could be generalized to a larger population in order to increase the rate of mammography screening.

Research is also needed to evaluate the effect of the screening program on the mortality of breast cancer. Design strategies need to consider past behavior regarding mammography screening as well as current recommendations. The strategies must also incorporate a discussion of beliefs regarding preventive health behaviors using variables of the EHBM, as well as reinforcement of regular screening behavior. It is also recommended that future studies lengthen the time intervals for data collection, as well as collect data at more than one point in time. Monthly data collection for 6 consecutive months would capture a more accurate picture of the response to the intervention. Moreover, a control group comparison at the same time intervals would further strengthen the study design.

Finally, it would be useful to add a post-mammogram survey in a future study to help determine the number of women who pursued follow-up care with their primary-care physician to address questions or concerns after receiving the home educational intervention. This may help to elucidate the impact that the intervention had on their decision to obtain mammography screening.

Conclusion

Mammography screening has been shown to be associated with a significant and substantial reduction in breast cancer mortality. However, every woman has the right to make an individualized, informed decision about her need for mammography screening. More educational resources promoting informed decision making by women are needed. Such resources will help all women, whether disabled or not, gain needed access to cancer screening.

Health-care providers have an ethical responsibility to provide optimal care for all patients, including those with disabilities. Health-care providers can set the stage for increasing access to health-care services for underserved populations by taking on leadership roles in the development of programs designed to provide these populations with evidence-based, compassionate health care.

Practice Points

Women with MS have a much lower annual rate of mammography screening for breast cancer than those without MS.

A variety of barriers to mammography screening in women with MS have been identified, including problems with physical mobility and cost of the procedure.

Interventions are needed to increase awareness of barriers to receipt of mammography screening in the MS population and thus reduce the disparity in screening rates between women with and without MS.

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2012. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2012.

US Preventive Task Force. Screening for breast cancer. Topic Page, July 2010. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsbrca.htm. Accessed August 12, 2012.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2001.

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Multiple Sclerosis Sourcebook. Atlanta, GA: National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 1999.

Rutledge D, Barsevick A, Knobf M, et al. Breast cancer detection: knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of women from Pennsylvania. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001; 28: 1032–1040.

Lauver D, Nabolz S, Scott K, et al. Testing theoretical explanations of mammography use. Nurs Res. 1997; 46: 32–39.

Savage S, Clark V. Factors associated with screening mammography and breast self-exam. Health Educ. 1996; 11: 409–421.

Lauver D, Kane J, Bodden J, et al. Engagement in breast cancer screening behaviors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999; 26: 545–554.

Beaulieu M, Beland F, Roy D, et al. Factors determining compliance with screening mammography. Can Med Assoc J. 1996; 154: 1335–1343.

Champion V. Compliance with guidelines for mammography screening. Cancer Detect Prev. 1992; 16: 253–258.

Champion V. Beliefs about breast cancer and mammography by behavioral stage. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1994; 21: 1009–1014.

Han Y, Williams R, Harrison R. Breast cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Korean American women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000; 27: 1585–1591.

Lagerlund M, Hedin A, Sparen P, et al. Attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge as predictors of nonattendance in a Swedish population-based mammography screening program. Prev Med. 2000; 31: 417–428.

Holm C, Frank D, Curtin J. Health beliefs, health locus of control, and women's mammography behavior. Cancer Nurs. 1999; 22: 149–156.

MacDowell N, Nitz-Weiss M, Short A. The role of physician communication in improving compliance with mammography screening among women ages 50–79 in a commercial HMO. Managed Care Quarterly. 2000; 8: 11–19.

Champion V, Miller A. Recent mammography in women aged 35 and older: predisposing variables. Health Care for Women International. 1996; 17: 233–245.

Matthews J. Adherence to Preventive Health Practice Among Family Caregivers of Persons Receiving Home Health Services [dissertation]. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh; 1997.

Lee J, Vogel V. Who uses screening mammography regularly? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1995; 4: 901–906.

Chan A, Heck C. Mobility in multiple sclerosis: more than just a physical problem. Int J MS Care. 2000; 3: 35–40.

Weinshenker B, Bass S, Rice G, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. Brain. 1989; 112: 133–146.

Beatty W. Memory and frontal lobe dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1993; 115: 583–591.

Deluca J, Johnson S, Natelson B. Information processing efficiency in chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1993; 50: 301–304.

Daly E, Komaroff A, Bloomingdale K, et al. Neuropsychological function in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple sclerosis, and depression. Appl Neuropsychol. 2001; 8: 12–22.

Aikens J, Fisher J, Namey M, et al. A replicated, prospective investigation of life stress, coping, and depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. J Behav Med. 1997; 20: 433–445.

Arnett P, Higginson C, Randolph J. Depression in multiple sclerosis: relationship to planning ability. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2001; 7: 665–674.

Schiffer R, Babigian M. Behavioral disorders in multiple sclerosis: temporal lobe epilepsy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an epidemiology study. Arch Neurol. 1984; 41: 1067–1069.

Strecher V, Rosenstock I. The Health Belief Model. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1997:41–58.

Stager J. The comprehensive Breast Cancer Knowledge Test: validity and reliability. J Adv Nurs. 1993; 18: 1133–1140.

Champion V. Revised susceptibility, benefits, and barriers scale for mammography screening. Res Nurs Health. 1999; 22: 341–348.

Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace and Company; 1996.

Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. “Mini-mental state,” a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975; 12:189–198

Financial Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.