Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Project Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) in Multiple Sclerosis

Background:

A pilot program using the Project Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) model was conducted for multiple sclerosis (MS) clinicians in the Pacific Northwest. The pilot was a collaboration between the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and faculty at the University of Washington. The goal was to determine the feasibility of using this telehealth model to increase the capacity and capability of clinicians in rural areas to treat people with MS.

Methods:

Thirteen practice sites with 24 clinicians were recruited to participate. Videoconferencing was used to conduct weekly sessions consisting of brief didactics followed by case consultations.

Results:

Most participants completing the outcome survey (10 of 15) indicated that they were more confident in treating patients with MS. They were satisfied with the training, felt better able to care for their patients, and had made changes in their treatment based on the case consultations and didactic content. They valued the case studies and case-based didactics and learned from each other as well as from the team.

Conclusions:

The pilot MS Project ECHO warrants further investigation regarding its potential effect on access to MS care delivery for underserved populations.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) requires a comprehensive approach to care and is limited by the shortage of MS-trained clinicians.1 Accessing MS care is especially challenging for people living in rural areas.2 Individuals with MS living in rural areas have reported lower levels of perceived quality of routine health care, MS-specific care, neurologist-provided care, mental health care, and home health care compared with their urban counterparts.3 4

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society (New York, NY) identified the Project Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) model to address gaps in MS care in collaboration with the University of Washington (UW) (Seattle, WA). Project ECHO improves the capacity to treat common, complex chronic diseases and monitor outcomes in rural and underserved areas.5 The four pillars of Project ECHO are 1) videoconferencing, to leverage scarce health-care resources; 2) sharing best practices, to reduce variability in care and innovate quickly; 3) using case-based learning, to maximize learning efficiency; and 4) monitoring outcomes through a Web-based database.5

Project ECHO in Washington State started with hepatitis C in 2008 and has expanded to other conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, addictions, and psychiatry.6 It operates regularly scheduled telehealth clinics that function as “knowledge networks” by bringing together expert interdisciplinary specialists from academic medical centers and community-based primary-care clinicians. Community clinicians learn best practices in chronic disease management through “learning loops,” in which they longitudinally co-manage patients with expert specialists and expand their knowledge through case-based learning. Over time, these learning loops result in deep knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy among participating clinicians. These new local experts offer state-of-the-art care in geographic areas that lack specialty physicians, thereby increasing access without having to recruit, retain, and fund additional clinicians. This approach may be the only way that high-quality treatments for many disorders can be delivered to rural residents. Importantly, Project ECHO has been shown to be as safe and effective as in-person specialty care at an academic medical center for the care of hepatitis C.7

MS differs from other diseases using Project ECHO: 1) MS has a lower prevalence (2.3 million people worldwide vs. 185 million people with chronic hepatitis C infection or 36.9 million people living with HIV/AIDS),8–10 and we did not know whether clinicians with few patients with MS in their practices would be willing to participate; 2) the Project ECHO model builds the confidence of clinicians by teaching practical practice protocols, or treatment guidelines, which are extremely limited in MS care; and 3) MS care is complex by nature, requiring not only diagnosis and medical intervention but also consideration of issues around psychosocial health, employment and community participation, and caregivers/partners.

In developing and piloting this MS Project ECHO, we had three objectives: 1) to develop MS-specific educational content and case consultation protocols; 2) to evaluate the feasibility, sustainability, and potential for replication of an MS Project ECHO; and 3) to identify an approach to assess the impact on the delivery of MS-specific care in underserved areas.

Methods

Setting

The National MS Society partnered with UW for this pilot program because of UW's experience using the Project ECHO model and its expertise in delivery of education to rural regions. The UW School of Medicine serves Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho.11

MS Project ECHO Team

The MS Project ECHO team included clinicians from the UW Medicine Multiple Sclerosis Center (three neurologists [G.S. and two nonauthors], two physiatrists [G.H.K. and a nonauthor], a rehabilitation psychologist [K.A.], and a rehabilitation counselor [K.L.J.]) and the UW Project ECHO program and staff from the National MS Society (providing information on community resources and educational materials). Based on the topic at hand, the team incorporated other experts from pharmacy, infectious diseases, and physical therapy. The role of medical director was filled by a physiatrist (G.H.K.) and then a neurologist (G.S.).

Program Development and Adaptation

The pilot MS Project ECHO, similar to most other Project ECHOs, involved a series of weekly 1-hour sessions with a brief didactic module followed by most time devoted to case consultation. Continuing education credit has been shown to improve both recruitment and retention of community clinicians and was provided. The pilot program was developed as a 12-week series so that the team could evaluate recruitment, retention, educational content, and the experience of participants and then revise the program for two subsequent series.

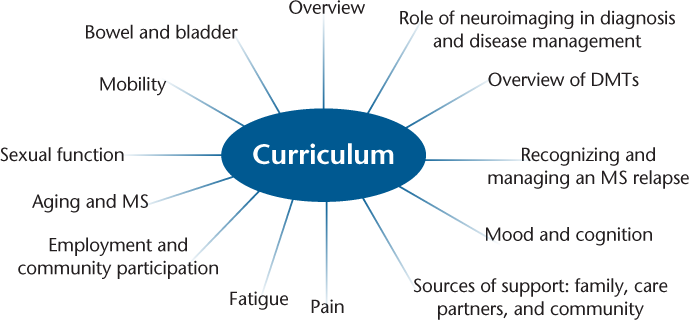

The team identified key educational elements that were practical and addressed the complex and comprehensive aspects of MS care to compose a preliminary syllabus (Figure 1). However, consistent with the Project ECHO model, the syllabus would be modified as the needs of the participating clinicians became more evident. Each educational module was assigned to an MS Project ECHO team member with expertise in that domain, who drafted content that was then reviewed by the team. Resources available through the National MS Society were included with each module. Presentation slides and associated reference materials were archived on the project website.

Educational content for MS Project ECHO syllabus

Given the high use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the diagnosis and monitoring of underlying MS disease, we recognized the importance of working with the participants in advance of their case presentations to obtain actual MRIs to integrate into the case study discussion in the weekly Project ECHO sessions. Review of actual case MRIs allowed for deeper instruction on the subtleties of MRI diagnosis and monitoring in MS. It was also a goal to allow for spontaneous case consultation, when time permitted, because the Project ECHO model is based on the development of a learning community where case presentations by participants result in expanded learning and exposure to a variety of MS care challenges.

Protection of Human Subjects

The Division of Human Subjects at UW determined that there was no risk to participants and that approval was not required.

MS Project ECHO Implementation

The phases of implementation consisted of recruitment, relationship building and mentoring, delivery of weekly sessions, between-session contact, and program evaluation.

Recruitment

We identified primary-care providers (PCPs) (physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants) or community specialists (neurologists or physiatrists) who cared for individuals with MS in the targeted region but who were not part of a multidisciplinary MS specialty center. We engaged in two phases of recruitment. Consistent with previous Project ECHOs, we focused initial recruitment efforts on PCPs, using a combination of strategies to recruit clinicians serving people with MS in rural Alaska, Idaho, Montana, and Washington State: sending notices to clinicians in the National MS Society's referral database for the desired locations and to participants in the UW HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C Project ECHOs and advertisements in the Health Resources and Services Administration newsletter to PCPs in the region. A few PCPs responded that implementation of the Affordable Care Act had resulted in an influx of newly insured patients, resulting in a lack of time for participation. We, therefore, expanded our outreach by sending notices to graduates of UW neurology and physiatry residency programs who practice in the targeted region and reaching out to clinicians known through professional relationships or recommended by National MS Society staff.

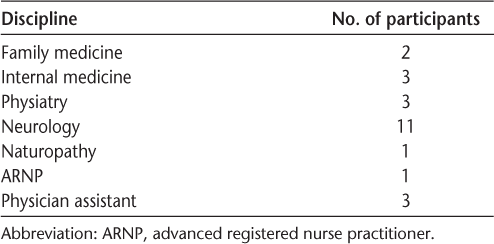

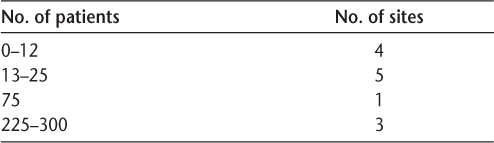

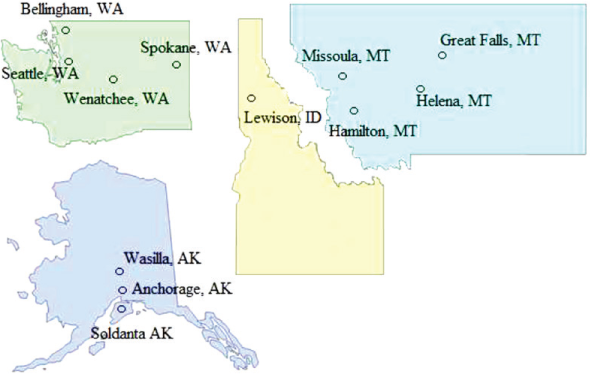

Thirteen clinical practice sites with 24 clinicians were recruited. A variety of other clinic staff at these sites also participated, including medical assistants, nurses, practice managers, and medical students. The resulting participants emerged from a diverse set of disciplines (Table 1), had vastly discrepant numbers of patients with MS (Table 2), and represented a diverse geographic region (Figure 2).

Number of participants by discipline

Number of patients with multiple sclerosis served at each practice site

Map showing distribution of practice sites across Washington, Alaska, Idaho, and Montana

Relationship Building and Mentoring

The success of the Project ECHO model depends on a trusting and respectful relationship between the Project ECHO team, especially the medical director, and the participating clinicians. Initial rapport was established through a site visit by the MS Project ECHO medical director to the participating sites, which included discussing the MS Project ECHO program, learning about the specific needs of the clinician related to MS care, and offering consultation. Often, the videoconferencing technology was delivered at the time and tested with the Project ECHO team, or alternatively it was shipped to the participant.

Throughout the program, participants were offered ongoing case consultation on an as-needed basis, educational content was modified to match the specific needs identified, and ongoing personal contact was made to encourage submission of cases for consultation. The MS Project ECHO medical director continually nurtured relationships, not only between himself and individual participants but among participants themselves, by establishing a relaxed learning environment. The medical director facilitated discussions during the Project ECHO sessions and was available outside of the Project ECHO sessions for questions and consultation.

Delivery of Weekly Sessions

For the purposes of the pilot, we offered three 12-week series. Participants were invited to continue participation even after a series concluded. Each session incorporated 20 to 30 minutes of didactic education followed by 30 to 40 minutes of case consultation. The program was scheduled over the lunch hour to maximize participant availability, noting, however, that the geographic region of the MS Project ECHO spanned three time zones, resulting in sessions falling outside of the desired window for the Alaska participants.

The videoconferencing platform allowed participants to see each other as well as the presentation slides and images. The presenting team used a dual TV monitor system that allowed them to manage the presentation and see all the participants.

Each session included the following: 1) A welcome by the medical director, introductions, agenda setting, and review of outstanding questions from previous sessions. An attendance form that included photographs of each participant was used by the consulting team to encourage name/face recognition. 2) A didactic presentation with PowerPoint slides and audience participation. 3) A review of relevant patient and clinician resources from the National MS Society. 4) Case presentations by participants, with facilitated discussion led by the medical director using MRIs and laboratory and clinical findings included in the slides. Discussion included multidisciplinary approaches to address patient needs. 5) Any follow-up on previous cases as time permitted. 6) A summary by the medical director.

Program Evaluation

The goal of this first phase of MS Project ECHO was to assess implementation of this model for MS specialty care. Throughout the program, the program manager collected information about attendance (participation was monitored and participants with low attendance were asked to provide their reasons for missing sessions) and participation in case consultations (the number of cases submitted for consultation, as well as the topics of the consultation requests, were tracked).

Participants were asked to complete exit interviews that included the following: clinician confidence: to indicate the impact of MS Project ECHO on the participant's confidence using a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 being the most positive impact; feedback on satisfaction with the program: to comment on the extent to which the program met their expectations; feedback on the program format: to comment on whether they preferred the current format of the program or had recommendations for future modification; feedback on the utility of National MS Society resources: to comment on whether they found the resources from the National MS Society useful, including providing specific examples of how they used those resources; feedback on the diversity of specialties in the participant group: given the decision to include participants who had varied specialties, we sought to understand whether this was viewed as positive or negative; feedback on participating in concert with trainees: several participants had medical students or residents with them during sessions, and we sought to understand whether it was beneficial to have them participate; and interest in future participation: to comment on their interest in future participation, which we considered one method for determining satisfaction with participation. We also asked participants to indicate barriers to future participation.

Results

Attendance

There were 24 participants at 13 sites, including 12 neurologists, three physiatrists, three internists, two family medicine specialists, three physician assistants, and one naturopathic physician. Participants were allowed to enter the program on a rolling basis. They engaged in 29% to 93% of the sessions available to them, with an average of 63% (ie, from the point they entered the program until they either withdrew or the program concluded). In follow-up evaluations, attendees with lower attendance cited the time commitment to participate or the specific time of the sessions as the primary barrier to participation. Participants with larger numbers of patients with MS tended to participate more frequently (76%–86%).

Participation in Case Consultations

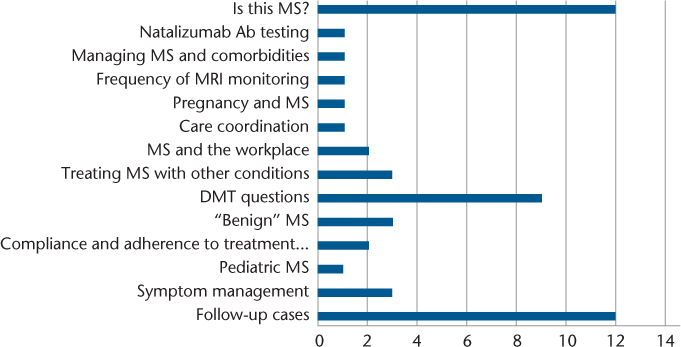

A total of 38 unique cases were presented by participants, and we returned to 12 of the cases for follow-up discussion. Sixty-eight percent of the patients were female, and the average age was 46 (range, 14–68) years. In Figure 3, the topics discussed during case presentations are shown. Case consultations often included more than one topic, resulting in the quantity of topics indicated exceeding the quantity of cases reviewed.

Topics discussed during case consultations

Clinician Confidence

Most participants responding to follow-up interviews (10 of 15) who were asked to rate the degree to which their confidence in treating MS on a scale from 1 to 5 indicated that MS Project ECHO increased their confidence “a lot” (mean = 4.53 of 5). Of the remaining five participants, three indicated that the program increased their confidence “a little” (one family practitioner caring for <10 patients with MS, one neurologist caring for >200 patients with MS, and one physiatrist caring for >200 patients with MS), and two participants (one pediatric neurologist caring for no patients with MS who attended only five total sessions and one neurologist caring for 10–20 patients with MS who attended nine sessions) answered “no change.” Notably, neither of these final two participants presented cases for case consultation.

Feedback on Satisfaction with Program

Nine of 15 participants (60%) also indicated that the program met their expectations. The remaining six participants stated that they had entered the program without specific expectations and, therefore, felt unable to evaluate whether it met expectations.

Feedback on Program Format

All the participants expressed good value in the sessions having both a didactic presentation and case consultation. Some participants (two generalists and one neurologist with 100–200 patients with MS) would have preferred more focus on the didactic portion of the sessions. Most participants expressed the value of the case consultations in helping to recognize the complexity of MS cases and how there is usually not one right answer to a question. Participants appreciated the variety of opinions from the “experts,” which added to their own confidence in delivering optimal MS care.

Feedback on Utility of National MS Society Resources

All the participants appreciated the involvement of the MS Society and the resources provided by the Society representatives. Most participants (n = 11 [73%]) were able to give specific examples of increased use of MS Society resources in their clinical practices as a result of MS Project ECHO. The most common examples were referral to the MS Navigator program and use of the National MS Society website and app.

Feedback on Diversity of Specialties in Participant Group

Thirteen participants (87%) appreciated having a mix of specialties represented; the other two were indifferent. One of the family practitioners expressed an interest in seeing more generalists participating. One of the neurologists expressed the value of having different viewpoints, giving an example of the approach from the generalists in treating depression. Several participants commented on the value of having a naturopathic physician as a participant because their viewpoint was unique in the treatment of certain symptoms, such as gastrointestinal tract dysfunction in MS. Many of the neurologists commented on the value of hearing the opinions of other neurologists and “not feeling alone” with some of the difficult decisions regarding disease-modifying therapies. A few of the generalists commented that at times the discussion was very specific to issues of the neurologists (decision making surrounding disease-modifying therapies) but they still appreciated listening to the discussion and learning that often there was no black-or-white answer to most questions.

Feedback on Participating in Concert with Trainees

A few participants had medical students sitting in with them during some sessions (n = 4 [27%]). These participants reported increased satisfaction in participation when the students were present. They felt that the MS Project ECHO sessions increased the teaching opportunities and improved the quality of the rotation for the students.

Interest in Future Participation

Most participants (n = 9 [60%]) expressed an interest in continuing to attend MS Project ECHO sessions. Participants reported that the videoconferencing format worked well for them. They appreciated the ability to switch quickly from the screen share mode with the presentation to the group mode where all participants could be seen. It was the observation of the MS Project ECHO team that a level of familiarity developed over time between participants and between participants and the expert panel, with interactions that seemed to support team-based learning and problem solving. The primary barrier to participation was the time of day or time constraints (n = 9 [60%]); participants were spread across three time zones (Alaska to Montana), so scheduling during the lunch hour was irrelevant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our MS Project ECHO program was the first MS-specific adaptation of the Project ECHO model, and the first to integrate with a nonprofit advocacy organization. Results of this feasibility pilot suggested that the model can be adapted and delivered successfully, with positive feedback, for community clinicians who care for individuals with MS.

We developed a curriculum that incorporated the comprehensive nature of MS care. A lesson learned, however, was the importance of being flexible to provide timely news (eg, a new Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment) and to address the questions that arose from participants. In terms of recruitment, although we were able to recruit 24 participants from rural and underserved communities, a lesson learned was to build in adequate time for extensive recruitment and to be flexible in terms of types of clinicians included. Another success was that we had continued good attendance, suggesting interest and value of the MS Project ECHO format. An additional lesson learned is that future MS Project ECHOs should have a sufficient budget to provide salary support for the team because this program requires considerable effort.

Based on our experience, and the feedback of participants, we saw evidence that the MS Project ECHO model capitalizes on key elements central to effective capacity-building programs, eg, by being interactive, taking place in the clinician's practice environment, and establishing rapport that improves participant engagement; in addition, the program emphasizes case-based learning, which has further been predictive of meaningful behavior change by clinicians.12–14 Given that Project ECHO capitalizes on relationships and runs as a hub-and-spoke model, we believe that there may be value in expanding delivery by geographic region.

Despite the success of the program, there were also a variety of challenges. First, although we strongly believe that building rapport with participants is essential to the success of Project ECHO, considering the schedules of the medical director and busy clinicians in the context of geographic differences and time zones was a challenge and necessitated creative alternatives, such as videoconferencing for several sites. Second, a key to the Project ECHO model is combining mentoring and patient case presentations, and we found it challenging to get some participants to come forward with cases. One explanation may be related to the small numbers of patients with MS seen by some participants. In addition, if MRIs were not available before the case presentation, they were obtained later and the case revisited. With increased direct requests either by telephone or e-mail from the medical director and program manager, we were able to increase the number of cases presented. Finally, financial sustainability is an important consideration. Although some Project ECHOs are funded by state or other dollars, others, including this MS Project ECHO, are funded by grants with finite endpoints.

Improving access to care is a high priority for people with MS. The National MS Society is committed to identifying strategies that reduce gaps in care and provide improved access to knowledgeable health-care providers. The phase 1 pilot of the MS Project ECHO suggests significant potential for improving access to MS care in rural and underserved communities. The pilot successfully identified both strengths and challenges of the program, and further exploration is warranted. Consistent with previous Project ECHOs, the feasibility phase should be followed by a replication with an outcomes assessment phase driven by clinician self-report of changes in domains such as knowledge, confidence, and professional isolation, as well as their perception of changes in the way they deliver care. Should this assessment yield meaningful outcomes, further assessment would involve patient-level data to better understand the true effect of the program on patient outcomes. And finally, evaluating the impact of connecting people with MS and their families to the National MS Society for the information, resources, and services they need will be an important outcome measure.

PracticePoints

MS care is complex, and the Project Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) model offers a way to expand access to care in rural areas by developing capacity and clinician confidence among primary-care and community neurologists.

Interdisciplinary MS care is difficult to achieve, especially in rural areas. The Project ECHO model provides interdisciplinary support and case consultation to clinicians in underserved areas.

Most participants in the pilot MS Project ECHO reported that they were satisfied with Project ECHO and that their confidence in treating people with MS increased.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Gloria Von Geldern, MD, and Annette Wundes, MD, UW Department of Neurology, and Piper Reynolds, Greater Northwest Chapter of the National MS Society, for their participation on the UW MS Project ECHO expert panel.

References

Drogan O. Multiple Sclerosis Workforce Survey Final Report. Minneapolis, MN: American Academy of Neurology; 2012.

Lishner DM, Richardson M, Levine P, Patrick D. Access to primary health care among persons with disabilities in rural areas: a summary of the literature. J Rural Health. 1996;12:45–53.

Buchanan RJ, Zhu L, Schiffer R, et al. Rural-urban analyses of health-related quality of life among people with multiple sclerosis. J Rural Health. 2008;24:244–252.

Buchanan RJ, Wang S, Stuifbergen A, et al. Urban/rural differences in the use of physician services by people with multiple sclerosis. Neuro-Rehabilitation. 2006;21:177–187.

Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med 2007;82:154–160.

Scott J, Unruh K, Catlin MC, et al. Project ECHO: a model for complex, chronic care in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18:481–484.

Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199–2207.

MS prevalence. National Multiple Sclerosis Society website. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/About-the-Society/MS-Prevalence. Accessed October 8, 2016.

Messina JP, Humphreys I, Flaxman A, et al. Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61:77–87.

Global Health Observatory (GHO) data: HIV/AIDS. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/gho/hiv/en. Accessed October 8, 2016.

Why UW School of Medicine. UW Medicine website. http://www.uwmedicine.org/education/md-program/admissions/why-uwsom. Accessed October 8, 2016.

Davis D, O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, et al. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282:867–874.

Sperl-Hillen J, O'Connor PJ, Ekstrom HL, et al. Educating resident physicians using virtual case-based simulation improves diabetes management: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Med. 2014;89:1664–1673.

Bullock A, Barnes E, Ryan B, Sheen N. Case-based discussion supporting learning and practice in optometry. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34:614–621.