Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Access to and Use of Clinical Services and Disease-Modifying Therapies by People with Progressive Multiple Sclerosis in the United Kingdom

Author(s):

Background:

According to current UK guidelines, everyone with progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) should have access to an MS specialist, but levels of access and use of clinical services is unknown. We sought to investigate access to MS specialists and use of clinical services and disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) by people with progressive MS in the United Kingdom.

Methods:

A UK-wide online survey was conducted via the UK MS Register. The inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older, primary or secondary progressive MS, and a member of the UK MS Register. Participants were asked about access to MS specialists, recent clinical service use, receipt of regular review, and current and previous DMT use. Participant demographic data, quality of life, and disease impact measures were from the UK MS Register.

Results:

In total, 1298 individuals responded: 7% were currently taking a DMT, 23% had previously taken a DMT, and 95% reported access to an MS specialist. The most used practitioners were MS doctors/nurses (50%), general practitioners (45%), and physiotherapists (40%). Seventy-four percent of participants received a regular review, although 37% received theirs less often than annually. Current DMT use was associated with better quality of life, but past DMT use was associated with poorer quality of life and higher impact of disease.

Conclusions:

Access to and use of MS specialists was high. However, a gap in service provision was highlighted in both receipt and frequency of regular reviews.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune demyelinating disease of the central nervous system that results in axonal and gray matter loss. It is estimated that there are 130,000 people living with MS in the United Kingdom.1 At the time of diagnosis, approximately 15% of people with MS are diagnosed as having primary progressive MS (PPMS); 80%, relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS); and 5%, progressive relapsing MS.2 Approximately 80% of those with RRMS will go on to develop secondary progressive MS (SPMS).2

Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are currently available to those who have RRMS or who are still experiencing relapses in the early stages of SPMS. Disease-modifying therapies have been found to delay the transition from RRMS to SPMS.3 Until recently, there were no effective licensed pharmacologic treatments for slowing the progression of disability in either PPMS or SPMS; however, ocrelizumab has now been shown to decrease disability progression by 25% in people with PPMS.3 Due to the lack of available effective pharmacologic treatments for disease activity in progressive MS, specialist rehabilitation services are of particular importance. Despite this, access to specialist services throughout the United Kingdom can be difficult, and people with progressive MS are often told that there is little available for them and are advised to self-manage their condition.4 The International Progressive MS Alliance has subsequently highlighted rehabilitation for people with progressive MS as a research priority,5 and disciplines such as physiotherapy have positive evidence in the rehabilitation of people with progressive MS.6

The current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for MS and Healthcare Improvement Scotland Clinical Standards for Neurological Health Services state that everyone with MS in the United Kingdom should have access to an MS specialist and receive a comprehensive regular review at least annually by a member of a multidisciplinary MS team.7 8 This review should cover all aspects of care (including medication, symptom management, disease course, general health, participation, and social care needs) and does not have to be conducted in a clinical environment. Recently, MS specialist nurses were found to be the most consulted health-care professionals,9 and 86% of people with MS reportedly had access to a neurologist or an MS nurse.10 However, these studies did not differentiate between MS types. In some areas of the United Kingdom, such as London and Northern Ireland, limited MS service provision has been found.11 12 Furthermore, in England and Wales, 55% of patient comments regarding provision of National Health Service (NHS) MS services were negative.13

The purpose of this study was to investigate access to and use of clinical services for people with PPMS and SPMS, specifically, exploring whether people with progressive MS had access to an MS specialist, what clinical services they used, if they received a regular review, their current and previous use of DMTs, and associations between these variables and quality of life and the physical and psychological impact of MS.

Methods

UK MS Register

The UK MS Register is an online register funded by the MS Society. People with MS become members voluntarily, and they answer both regular and online surveys.14 Members self-report their MS diagnosis type and demographic information and complete self-report outcome measures, such as the three-level version of the EQ-5D (EQ-5D-3L) health questionnaire (EuroQol) and the physical and psychological subscales of the 29-item Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) every 3 months. Data are anonymized using the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage system.15 At the time of this study there were 11,041 people on the UK MS Register, with 4384 people active on the Register in the previous 6 months.

Design and Participant Recruitment

A cross-sectional survey design was used. The survey was available on the UK MS Register from August to October 2015. To be eligible for inclusion, a participant had to be 18 years or older, living in the United Kingdom, diagnosed as having progressive MS, and registered on the UK MS Register. Potential participants were identified by the UK MS Register and were informed of the survey by e-mail. The survey was accessed only via the UK MS Register, and completion was regarded as informed consent. Ethics approval was obtained from the College of Medical, Veterinary, and Life Sciences Ethics Committee, University of Glasgow, and the study underwent peer review by the information governance panel of the UK MS Register (South West–Central Bristol Research Ethics Committee [Ref: 11/SW/0160]).

The survey was in two sections. The first asked about access to, experiences with, and opinions of physiotherapy services and complementary therapies in the United Kingdom and has been described elsewhere.16 The second section asked whether a participant had access to an MS specialist, defined as a clinician with MS specialist skills. Participants were also asked which clinicians they consulted in the previous 3 months for their MS. Participants were asked whether they received a regular review for their MS, how often that review took place, who normally undertook the review, and where the review normally took place. Finally, previous and current use of DMTs was explored, and participants were asked to select whether they were currently taking, or had previously taken, any of the following: beta-interferon (Rebif [EMD Serono Inc, Rockland, MA], Avonex [Biogen, Cambridge, MA], Betaseron [Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Montville, NJ]), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone [Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, North Wales, PA]), dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera [Biogen]), teriflunomide (Aubagio [Genzyme Corp, Cambridge, MA]), natalizumab (Tysabri [Biogen], Antegren [Biogen]), fingolimod (Gilenya [Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp, East Hanover, NJ]), mitoxantrone (Novantrone [EMD Serono Inc, Rockland, MA]), and alemtuzumab (Lemtrada [Genzyme Corp]). A copy of the survey is available on request. Due to the structural progression of the survey, not all participants answered all questions.

Access

This study explored two components of access: the opportunity to enter into the service (regardless of organizational barriers such as waiting times and distance to travel) and the use of services.17 In this survey, these two components were referred to as access and use, respectively. Although these terms were not explicitly explained, their meaning was implied by questions asked; for example, “Which of the following clinicians could you see if you wanted to?” implied the availability of the opportunity to see a clinician and “Which of the following clinicians have you seen in the past 3 months for your MS?” implied the use of services. Barriers to accessing physiotherapy were explored in some detail and have been published elsewhere.16

Access to an MS Specialist

Participants were asked whether they had access to an MS specialist service. If they answered “yes” they were then asked which clinicians they had seen recently for their MS. If they answered “no” they were then asked which clinicians they could see if they wanted to. Included in this list were MS specialist nurse and MS specialist doctor/neurologist. The answers of those who reported having access to an MS specialist service and of those who reported that they could see an MS specialist nurse or doctor were combined. This gave the total level of access to MS specialists for this cohort.

Additional Data from UK MS Register

In addition to data collected from the survey, the following data routinely collected by the UK MS Register were accessed: type of MS, age, sex, time since diagnosis of MS, quality of life as measured by the EQ-5D-3L, the physical and psychological subscale scores of the MSIS-29, and Lower Super Output Area codes (England and Wales) and Output Area codes (Scotland) (there were no available geographic data for participants from Northern Ireland). Lower Super Output Area codes and Output Area codes, which are used to tabulate census and statistical data by the Office of National Statistics, were combined with data available from the Office for National Statistics and the Scottish Office for National Statistics18 19 to generate the following information: rural or urban dwelling and Strategic Health Authority for participants in England (in 2013, NHS England divided England into ten regions called Strategic Health Authorities, each of which contained multiple NHS trusts). Rural dwelling was defined as a settlement with a population of 10,000 or less.20

The EQ-5D-3L is a self-report measure of quality of life generating an index ranging from −1 to 1, with a higher index indicating a better quality of life.21 The MSIS-29 is a 29-item self-report measure with physical and psychological subscales to measure the impact of MS.22 The physical subscale score ranges from 20 to 80, and the psychological subscale score ranges from 9 to 36. A lower score indicates a lower impact of MS.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize demographic data and all the outcome variables. Due to programming and structure of the survey not all participants answered every question, therefore, responses to individual questions are presented as percentages of number of respondents to that question. Data were tested for normality, and due to nonnormal distribution, χ2 and Mann-Whitney tests were used as appropriate. A significance level of P < .05 was used.

Results

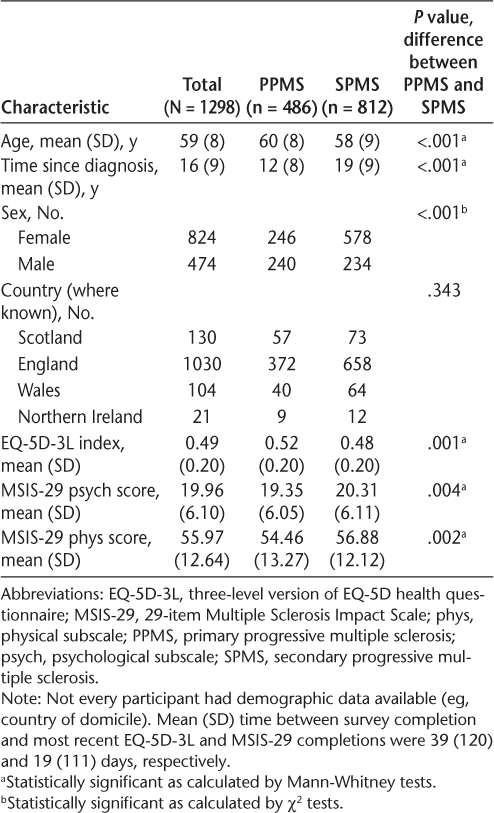

Of 2538 registrants with progressive MS who were e-mailed by the UK MS Register, 1298 completed the survey, generating a 51% response rate (England: n = 1030, Scotland: n = 130, Wales: n = 104, and Northern Ireland: n = 21 [13 participants had not supplied their geographic data to the UK MS Register]). Participants had a mean (SD) age of 59 (8) years and time since diagnosis of 16 (9) years; the female-male ratio was 1.7:1; 486 (37%) had PPMS and 812 (63%) had SPMS. The mean (SD) EQ-5D-3L index was 0.49 (0.20), indicating a poorer quality of life compared with the general population of the same age who would have an approximate index of 0.8.23 The mean (SD) MSIS-29 physical and psychological subscores were 55.97 (12.64) and 19.96 (6.10), respectively, indicating that this sample was moderately affected physically and psychologically by their MS (Table 1). Compared with those with SPMS, people with PPMS were older and had a shorter time since diagnosis, a higher EQ-5D-3L index, and lower psychological and physical scores on the MSIS-29 (all P < .005).

Demographic characteristics of survey participants

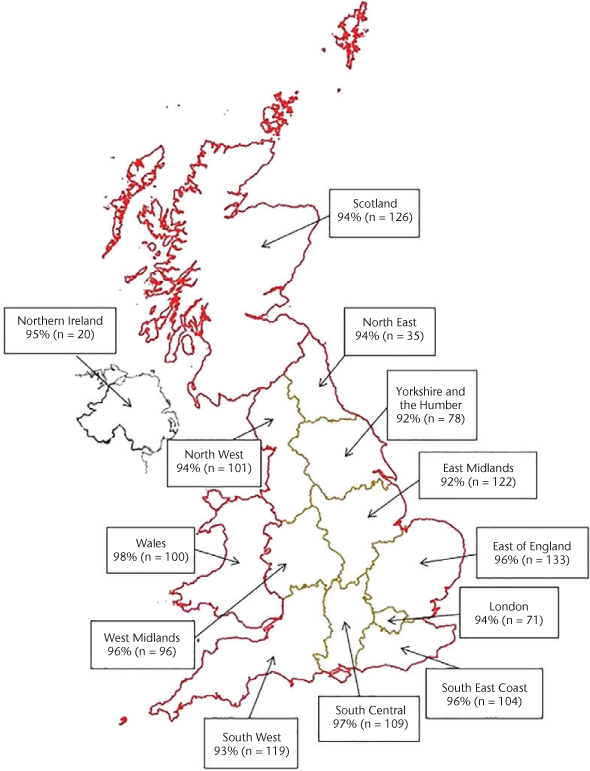

In total, 1184 participants (95%) reported that they had access to an MS specialist, and 959 (81%) of those who had access reported they would be able to access the specialist if their symptoms or needs changed. Figure 1 shows access to MS specialists across the United Kingdom. Access to an MS specialist ranged from 92% in Yorkshire and the Humber and the East Midlands to 98% in Wales.

Access to multiple sclerosis (MS) specialists across United Kingdom

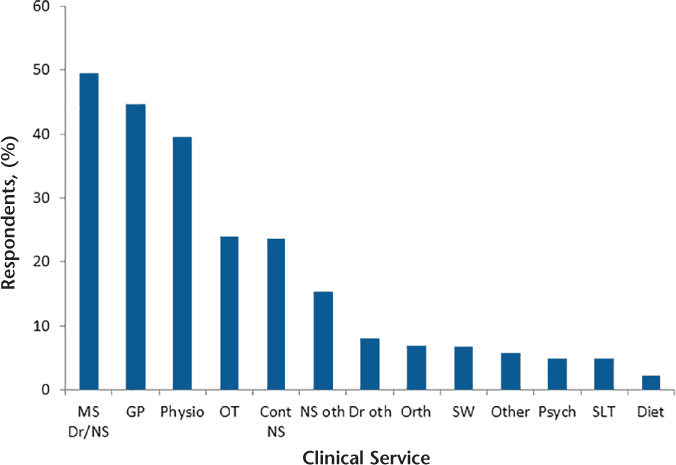

Overall, 1046 participants (81%) reported using clinical services for their MS in the previous 3 months. The most commonly used clinical services were MS specialist doctors/nurses (n = 517 [49%]), general practitioners (n = 467 [45%]), and physiotherapists (n = 414 [40%]) (Figure 2). Of the participants receiving clinical services for their MS, 481 (46%) were receiving a single service and 565 (54%) were receiving more than one service. Of the 447 participants who answered the question, 88 (20%) reported that they were currently taking a DMT (PPMS: n = 18, SPMS: n = 70). Of the 1241 participants who answered the question, 303 (24%) reported that they had previously taken a DMT (PPMS: n = 37, SPMS: n = 266). This equated to 7% of the sample currently taking a DMT and 23% having previously taken a DMT.

Clinical services used by participants for their multiple sclerosis (MS) in past 3 months

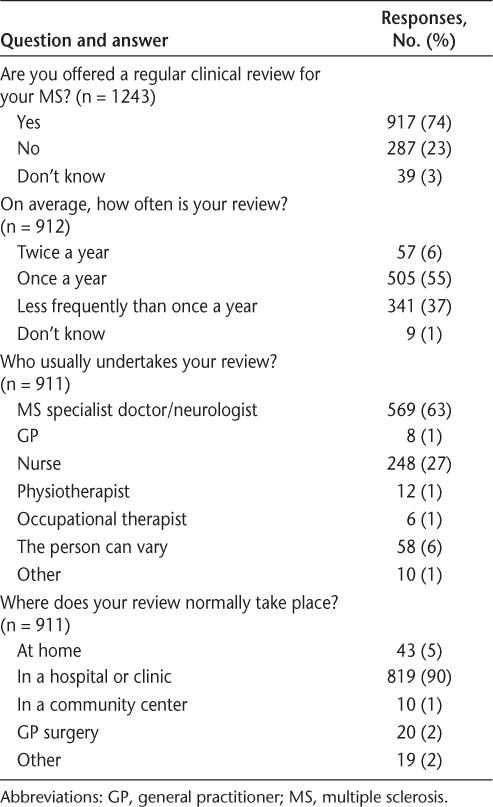

In total, 917 of 1243 participants (74%) received a regular review; 505 (55%) received that review annually. Of 911 respondents, 569 (63%) had their review performed by an MS specialist doctor, and 248 (27%) reported that it was performed by a nurse. A total of 819 of 911 participants (90%) reported usually receiving their review in a hospital or clinic (Table 2). Ninety percent of participants who were currently taking a DMT received a regular review: 6% received their review twice a year, 51% once a year, 41% less frequently than once a year, and 2% did not know (data not shown).

Survey responses regarding a regular review for progressive MS

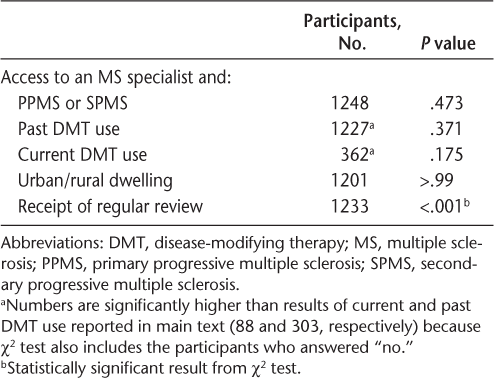

There was a significant association between access to an MS specialist and receiving a regular review (P < .001) (Table 3). Access to an MS specialist was not associated with MS type, past or present DMT use, or urban/rural dwelling (Table 3).

Associations between access to an MS specialist and MS type, DMT use, dwelling location, and receipt of regular review

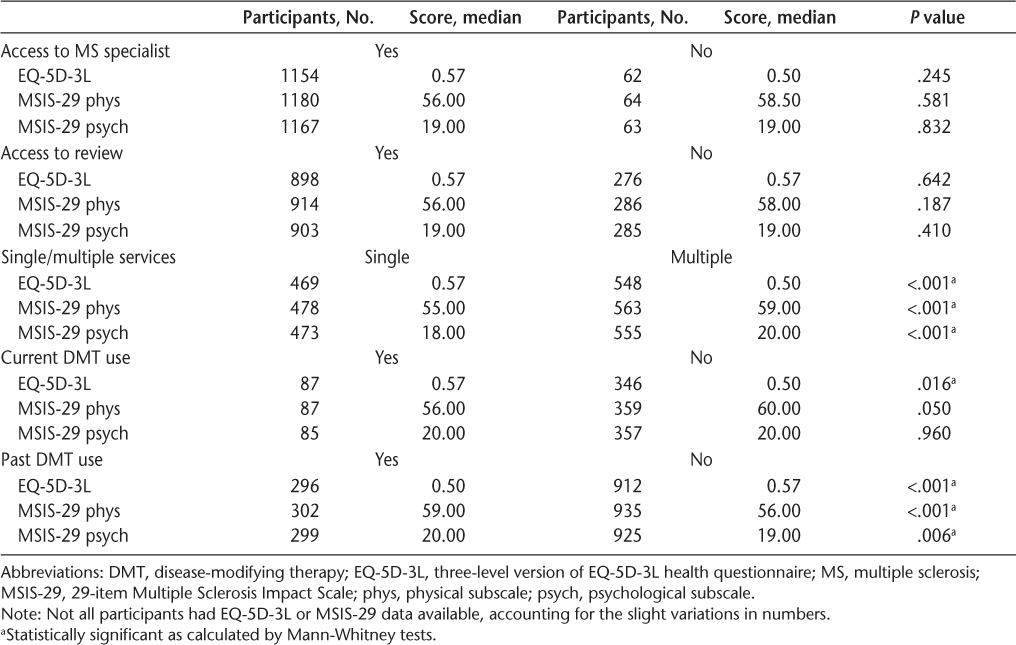

Participants who received a single clinical service, as opposed to multiple services, for their MS had a better quality of life as measured by the EQ-5D-3L index (P < .001) and less of a physical and psychological impact of MS as measured by the MSIS-29 (P < .001). Use of single or multiple services was, however, not dependent on MS type (n=1045, P = .165) or whether a participant lived in a rural or urban location (n = 1003, P = .972) (data not shown). Participants who were currently taking a DMT for their MS had a better quality of life (P = .016) than those who were not taking a DMT. Those who had previously taken DMTs, however, had a poorer quality of life (P < .001) and greater physical (P < .001) and psychological (P = .006) impacts than those who had not taken DMTs (Table 4). There were no differences in quality of life and disease impact scores between those who did and did not have access to an MS specialist or access to a review, and there was no difference in the psychological or physical impact of MS between those who were and were not currently taking a DMT (Table 4).

Differences in EQ-5D-3L and MSIS-29 scores by access to an MS specialist, regular review, receipt of MS service, and DMT use

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study had the largest sample solely of people with progressive MS to be surveyed to date and was the first to investigate access to and use of clinical services for people with progressive forms of MS across the United Kingdom.

In this sample of 1298 individuals with MS, access to an MS specialist was high (95%) and was similar across the United Kingdom (Figure 1). This was slightly higher than the outcome of a survey performed by the MS Society in people with all types of MS in the United Kingdom that reported that 86% of participants had access to a neurologist or MS nurse.10 A previous study conducted in London reported a lack of access to MS-related services among those severely affected by MS11; however, the present study indicates that 95% of people with progressive MS have access to an MS specialist. This difference in results may indicate improvements in service provision since Edmonds et al.11 performed their study and that the people in this sample were not severely affected by their MS. Interestingly, there were no differences in quality of life and disease impact measures between those who did and those who did not have access to an MS specialist. However, there were relatively few people who did not have access in these analyses, so results should be interpreted with caution.

Although access to MS specialists was high, not all received a regular review, as is recommended by current guidelines and standards.7 8 Just less than three-quarters of participants received a regular review, and 37% of these received their review less frequently than annually. This is a breach of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines and the Healthcare Improvement Scotland clinical standards. With the potential advent of pharmacologic treatments for PPMS disease activity,3 a regular clinical review will in the future be particularly important in the care of people with progressive MS. Indeed, of those who were currently receiving a DMT, 90% were in receipt of a regular review, but only 57% received that review once a year or more frequently. However, note that there were no differences in quality of life or disease impact measures between those who did and did not receive a regular review.

Use of clinical services in this study's participants was high. The three most used clinical services were MS specialist nurses or doctors, general practitioners, and physiotherapists (Figure 2). This finding was similar to two previous studies surveying people with all types of MS in the United Kingdom and Europe.9 24 This may indicate that people with progressive MS are using the same kinds of clinical services as those with RRMS.

Similar proportions of participants received multiple services (54%) or a single service (46%) for their MS. Those who received a single service for their MS had a better quality of life and lower psychological and physical impacts of MS compared with those who received multiple services, which may be a reflection of clinical need and, in turn, is likely to be associated with disability level.

There was no association between rural or urban dwelling and access to an MS specialist or receiving a regular review. Previous research by Lonergan et al.25 in the Republic of Ireland found that a lack of access to services was associated with rural dwelling. These researchers, however, surveyed people with all types of MS, and 37% of the population live rurally in the Republic of Ireland, compared with 18% in the United Kingdom,26 which may explain the differences in results reported. Furthermore, the lack of association between rural and urban living and access to an MS specialist may be due to the definition of access used in this study being the opportunity to see a clinician regardless of personal and organizational barriers.

Seven percent of this sample was currently taking a DMT, and 23% had been prescribed them previously. This result is lower than previously reported by the MS Society, which found that 56% of all people with all types of MS in United Kingdom were taking a DMT.10 This difference is expected as prescribing guidelines state that DMTs are not effective in progressive forms of MS when relapses are not present27 and that those taking a DMT currently may have been prescribed them while in the relapsing-remitting phase of MS. The 7% of participants still taking a DMT does, however, contribute further to the importance of a regular clinical review because there are potentially a large number of people with MS inappropriately taking these drugs in the United Kingdom. Furthermore, those taking a DMT had a better quality of life compared with those who were not. Those who had previously taken DMTs, however, had a poorer quality of life and greater physical and psychological impacts of MS compared with those who had never taken them. These differences were, however, small and may be an indication of the stage of disease because those who are no longer taking a DMT may have more advanced disease and may have transitioned into the secondary progressive phase, for which DMTs are no longer appropriate.

This study has several limitations. The open and voluntary nature of the UK MS Register and online surveys leaves the sample open to bias to the motivated and those with a vested interest. In addition, those who are more severely disabled and find it difficult to access services may not be on the register. The diagnosis and type of MS was self-reported, but in the future the UK MS Register will be linked to clinical data from the NHS. The concept of access is multifaceted and although the definition of access as the opportunity to see a clinician was implied by the questions asked, it was not implicitly defined, which may have affected responses. For example, even if participants thought that their clinician was not available due to a long waiting list, they may have selected that they did not have access. A programming error lead to the responses regarding access to and use of MS doctors and MS nurses being combined, and they were thus combined in the results. There were no geographic data available for participants in Northern Ireland, which limited the analysis comparing participants living in rural and urban settings. Participants may have encountered problems with memory recall when asked about the regularity of review. This may have resulted in errors in reporting, with those who more recently received their review being more likely to report it. Last, owing to the conditions of ethical approval, it was not possible to examine the demographic features of those who did not respond to the survey to determine whether they were typical of registrants of the UK MS Register with progressive MS.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this was the first survey of its kind examining access to and use of clinical services by people with progressive MS in the United Kingdom, and it had the largest sample of people with progressive MS to date. Access to an MS specialist was high, and use of clinical services for participants with MS was also high. However, a gap in service provision, which breaches national guidelines, was found in relation to regular reviews, and health-care providers in the United Kingdom should address this. Furthermore, investigation should also establish the effectiveness of and patient satisfaction with services used.

PracticePoints

The level of access to MS specialists by people with progressive MS in the United Kingdom was 95%.

The most used practitioners by participants for their MS were MS specialist doctors/nurses, general practitioners, and physiotherapists.

The level of access to a regular clinical review was 74%; however, 37% of participants received their reviews less often than annually, falling short of the recommended guidelines.

Financial Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Mackenzie IS, Morant SV, Bloomfield GA, MacDonald TM, O'Riordan J. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the UK 1990–2010: a descriptive study in the General Practice Research Database. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:76–84.

Miller DH, Leary SM. Primary-progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:903–912.

Montalban X, Hemmer B, Rammohan K, et al. Efficacy and safety of ocrelizumab in primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of the phase III double-blind, placebo-controlled ORATORIO Study (S49.001). Neurology. 2015;86:S49.001.

Holland NJ, Schneider DM, Rapp R, Kalb RC. Meeting the needs of people with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, their families, and the health-care community. Int J MS Care. 2011;13:65–74.

Fox RJ, Thompson A, Baker D, et al. Setting a research agenda for progressive multiple sclerosis: the International Collaborative on Progressive MS. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1534–1540.

Campbell E, Coulter EH, Mattison PG, Miller L, McFadyen A, Paul L. Physiotherapy rehabilitation for people with progressive multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;97:141–151.e143.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multiple Sclerosis in Adults: Management. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2014. NICE clinical guideline 186.

Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Clinical Standards for Neurological Health Services. Edinburgh, UK: Healthcare Improvement Scotland; 2009.

Mynors G, Suppiah J, Bowen A. Evidence for MS Specialist Services: Findings from the GEMSS MS Specialist Nurse Evaluation Project. Letchworth Garden City, UK: Multiple Sclerosis Trust; 2015.

MS Society. My MS My Needs 2016: Access to Treatment and Health Care. London, UK: MS Society; 2016.

Edmonds P, Vivat B, Burman R, Silber E, Higginson IJ. “Fighting for everything”: service experiences of people severely affected by multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:660–667.

MacLurg K, Reilly P, Hawkins S, Gray O, Evason E, Whittington D. A primary care-based needs assessment of people with multiple sclerosis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:378–383.

Markwick R, Singleton C, Conduit J. The perceptions of people with multiple sclerosis about the NHS provision of physiotherapy services. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:131–135.

Ford DV, Jones KH, Middleton RM, et al. The feasibility of collecting information from people with multiple sclerosis for the UK MS Register via a web portal: characterising a cohort of people with MS. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:73.

Jones KH, Ford DV, Jones C, et al. A case study of the Secure Anonymous Information Linkage (SAIL) Gateway: a privacy-protecting remote access system for health-related research and evaluation. J Biomed Inform. 2014;50:196–204.

Campbell E, Coulter EH, Mattison PG, Miller L, McFadyen A, Paul L. Access, delivery and perceived efficacy of physiotherapy and use of complementary and alternative therapies by people with progressive multiple sclerosis in the United Kingdom: an online survey. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;12:64–69.

Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:18.

Office for National Statistics. 2011 rural/urban classification. https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/geography/geographicalproducts/ruralurbanclassifications/2011ruralurbanclassification. Accessed January 21, 2016.

Scottish Office for National Statistics. 2011 census indexes. http://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/geography/our-products/census-datasets/2011-census/2011-indexes. Accessed January 21, 2016.

Department for Communities and Local Govenment. Urban and rural area definitions: a user guide. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120919132719/http:/www.communities.gov.uk/documents/planningandbuilding/pdf/156303.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2016.

EuroQol Group. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

Hobart J, Lamping D, Fitzpatrick R, Riazi A, Thompson A. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): a new patient-based outcome measure. Brain. 2001;124(pt 5):962–973.

Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, Mulhern B, van Hout B. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England [published online August 22, 2017]. Health Econ. doi:10.1002/hec.3564.

Kersten P, McLellan DL, Gross-Paju K, et al. A questionnaire assessment of unmet needs for rehabilitation services and resources for people with multiple sclerosis: results of a pilot survey in five European countries. Clin Rehabil. 2000;14:42–49.

Lonergan R, Kinsella K, Fitzpatrick P, et al. Unmet needs of multiple sclerosis patients in the community. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4:144–150.

The World Bank. World development indicators: rural environment and land use. http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/3.1. Accessed June 14, 2016.

Scolding N, Barnes D, Cader S, et al. Association of British Neurologists: revised (2015) guidelines for prescribing disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. Pract Neurol. 2015;15:273–279.