Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Triaging Patients with Multiple Sclerosis in the Emergency Department

Background:

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) present to the emergency department (ED) for various reasons. Although true relapse is rarely the underlying culprit, ED visits commonly result in new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and neurology admissions. We studied ED visits in patients with MS and evaluated decision making regarding diagnostic/therapeutic interventions and visit outcomes. We identified potential areas for improvement and used the data to propose a triaging algorithm for patients with MS in the ED.

Methods:

We reviewed the medical records from 176 ED visits for patients with MS in 2014.

Results:

Ninety-seven visits in 75 patients were MS related (66.6% female; mean ± SD age, 52.6 ± 13.8 years; mean ± SD disease duration, 18.5 ± 10.5 years). Thirty-three visits were for new neurologic symptoms (category 1), 29 for worsening preexisting symptoms (category 2), and 35 for MS-related complications (category 3). Eighty-nine visits (91.8%) resulted in hospital admission (42.7% to neurology). Only 39% of ordered MRIs showed radiographic activity. New relapses were determined in 27.8% of the visits and were more prevalent in category 1 compared with category 2 (P = .003); however, the two categories had similar rates of ordered MRIs and neurology admissions.

Conclusions:

New relapse is a rare cause of ED visits in MS. Unnecessary MRIs and neurology admissions can be avoided by developing a triaging system for patients with MS based on symptom stratification.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) affects approximately 350,000 people in the United States, with approximately 12,000 new diagnoses each year.1 The high cost of treatment, disability, and loss of productivity throughout the disease course is a great burden to society.2 A cross-sectional study of patients with MS in the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry estimated that the average annual cost per patient was greater than $47,000.3 A study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample looked at overall trends of MS hospital admissions from 1993 through 2006. Over the 14-year period, the percentage of patients with MS admitted from the emergency department (ED) increased from 19.4% to 60.0%. The average cost per admission increased from $7965 in 1993 to $20,076 in 2006, with a total MS population cost of $445 million.4 In addition to the cost of disease-modifying therapy (DMT) and imaging, it is known that hospital admissions also contribute considerably to the cost of managing MS.5 6 Although hospitalization may be necessary in severe acute exacerbations, most patients with less severe relapses and those with pseudorelapses can be treated as outpatients. When patients are hospitalized for management of acute exacerbations, the cost increases approximately six times compared with patients who are treated as outpatients. Patients admitted from the ED compared with those admitted by their outpatient physicians had even higher admission costs.7

Patients with MS visit the ED for various reasons, including relapses, pseudorelapses (temporary worsening of preexisting deficits), medical complications, and treatment-related adverse effects.8 9 In the absence of clear guidelines on triaging patients with MS in the ED, there is great variability in the course of action taken at each hospital, which results in a large number of unnecessary tests, consultations/admissions, and treatments and, ultimately, adds to the high economic burden of this chronic disease.

Establishing a triaging system and clear guidelines on handling patients with MS in the ED can translate into better patient care by avoiding treatment delays and promoting faster patient discharge while also reducing the cost of medical services.10 This process requires careful evaluation of common shortcomings and prevalent patterns of improper stratification of patients with MS in the ED. This study aimed to identify potential areas of improvement when handling patients with MS in the ED so that a comprehensive triaging system and preliminary guidelines for MS hospital admissions can be developed.

Methods

Patient Search and Visit Categorization

Cleveland Clinic Health System electronic medical records were searched for patients with an MS diagnosis who had ED visits from January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2014. Visits that were clearly unrelated to MS were excluded from further analysis, for example, patients with comorbid conditions presenting with acute coronary syndrome, diabetic complications, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations, and postoperative complications unrelated to MS. We classified the remaining visits into three categories: category 1, visits for new neurologic symptoms; category 2, visits for worsening of preexisting neurologic symptoms; and category 3, visits for nonneurologic MS-related complications. Category 1 was defined as involvement of a new body part never affected by an MS attack previously or involvement of a new neurologic system in a previously affected body part (eg, new motor weakness of a limb previously affected by a sensory deficit). Patients with new neurologic symptoms were included in this category even if the new neurologic symptoms were not typical of MS, such as seizures, painless vision loss, or cognitive decline. Category 2 was defined as worsening of the same neurologic system in a previously affected body part (eg, worsening limb weakness in a weak limb from previous relapse, worsening vision in an eye with a history of optic neuritis). Category 3 includes various MS-related nonneurologic complications, such as falls/trauma secondary to weakness or ataxia, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) from immobility, urinary tract infections (UTIs) or urosepsis secondary to bladder dysfunction, and aspiration pneumonia secondary to bulbar dysfunction. Medical records were carefully reviewed to differentiate visits unrelated to MS (and, therefore, excluded from further analysis) from those directly or indirectly related to MS even for the same patient. For example, a visit for immobility-related DVT was included as category 3, whereas a visit for angina in a patient with vascular risk factors was considered unrelated to MS and thus was not analyzed. Moreover, categorization was strictly based on the presenting symptom and not on the final diagnosis; for example, a visit with a new UTI was categorized as category 2 if the patient presented with worsening weakness/numbness or as category 3 if the patient presented with fever and dysuria. For each category, the following variables were analyzed: patient demographics, outpatient team contact before ED presentation, ED/hospital interventions (imaging, corticosteroids), visit outcome (discharge, neurology admission, or other admission), presence of UTI or other infection, and presence of new MS relapse.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance was used to compare differences among the three categories. In addition, we used t and χ2 tests to compare categories 1 and 2 separately because these two categories are substantially different from category 3 and differentiating the two is more clinically challenging in the ED setting. We also compared patients in whom a new MS relapse was determined at the end of the ED visit or hospital admission (as determined by the neurology team) with those in whom a new relapse was excluded or not considered regardless of the visit category. The data were used to identify potential areas of improvement. This study was approved for review exemption by the Cleveland Clinic's institutional review board.

Results

Overview

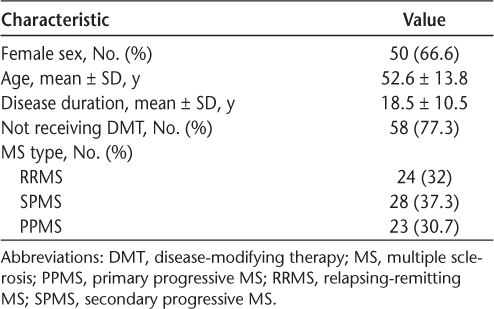

A total of 176 ED visits pertaining to 94 patients with MS in 2014 were identified and reviewed. Seventy-nine visits were unrelated to MS and were thus excluded. The remaining 97 visits pertaining to 75 patients with MS were further analyzed. See Table 1 for patients' demographic characteristics.

Demographic characteristics of the 75 study patients

In total, new brain or spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained in 38 visits (39.2%), of which only 15 (39.5%) showed evidence of radiographic disease activity. Eighty-nine visits (91.8%) resulted in hospital admission, of which 38 (42.7%) were to neurology. Corticosteroids were given in 24 visits (24.7%). A new relapse was determined in 27 visits (27.8%), and UTIs were found in 30 (30.9%). Telephone calls to the outpatient treatment team or the nurse/resident on call before ED presentation were infrequent (8.2%).

Visit Categories

Category 1: New Neurologic Symptoms

There were 33 ED visits for new neurologic symptoms, with a new MRI ordered in 21 (63.6%), of which only 11 (52.4%) showed evidence of radiologic activity. Twenty visits (60.6%) resulted in admission to neurology, ten in admission to other services, and three in discharge from the ED. A new relapse was determined in 20 visits (60.6%), and other causes were found in 13 (39.4%). These other causes included UTI (eight visits) (mostly presenting with new sensory symptoms) and septic emboli, seizure secondary to subdural hematoma, dementia, vitreous hemorrhage (presenting with painless vision loss), and conversion disorder (one visit each). Corticosteroid treatment was given in 17 visits (51.5%).

Category 2: Worsening Neurologic Symptoms

There were 29 ED visits for worsening preexisting neurologic symptoms. Fourteen new MRIs (48.3%) were ordered in this category, but only four (28.6%) showed evidence of radiographic activity. Most visits in this category (n = 27) resulted in hospital admission, of which 13 (48.1%) were to neurology. A true relapse was determined in seven visits (24.1%), and in all of them there was a substantial quantitative change in the degree of the previously documented deficit from the latest available neurologic examination on record.

Other causes of worsening preexisting symptoms included UTI (ten cases; 34.5%), other infections (three; 10.3%), ileus/constipation/stool impaction (three; 10.3%), and others (one each): worsening tonic spasms, trigeminal neuralgia relapse, baclofen pump overdose, functional/somatoform symptoms, migraine, and adrenal insufficiency. Corticosteroids were given in seven visits (24.1%).

Category 3: Nonneurologic Symptoms

We identified 35 visits for nonneurologic MS-related complications: urinary symptoms secondary to UTI (n = 12), fall/fracture/subdural hematoma (n = 6), aspiration pneumonia (n = 4), back/hip pain from immobility (n = 3), MS medication adverse effects (n = 2), constipation/percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube malfunction (n = 2), fever/sepsis (n = 2), infected pressure ulcer (n = 1), immobility-related DVT (n = 1), hemorrhage after thrombolytic therapy for DVT (n = 1), and wrist swelling after flexor spasm (n = 1). Three MRIs were performed in this category looking for intracranial pathology after falls or seizures. Five visits resulted in neurology admission (14.3%), whereas most admissions were to other services (77.1%). No corticosteroid treatments were given in this visit category.

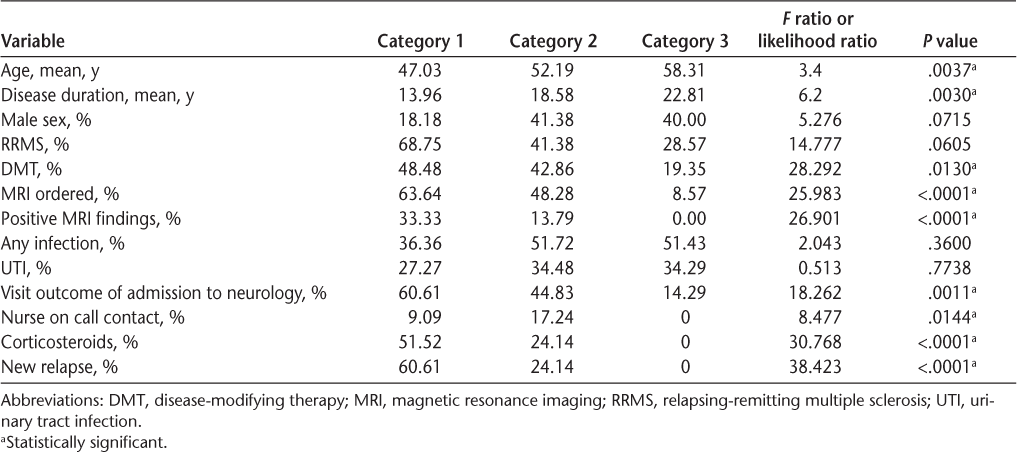

Statistical Analysis

Table 2 shows the results of analysis of variance among the three visit categories. Expectedly, the three categories had statistically significant between-group differences in age, disease duration, DMT use, nurse on call contact, MRI ordered, MRI positivity, corticosteroid treatment, ED visit outcome, and prevalence of new relapses. There was no statistically significant difference between groups in sex, MS type, presence of UTI, or presence of any infection.

Patient characteristics and visit outcomes by visit category

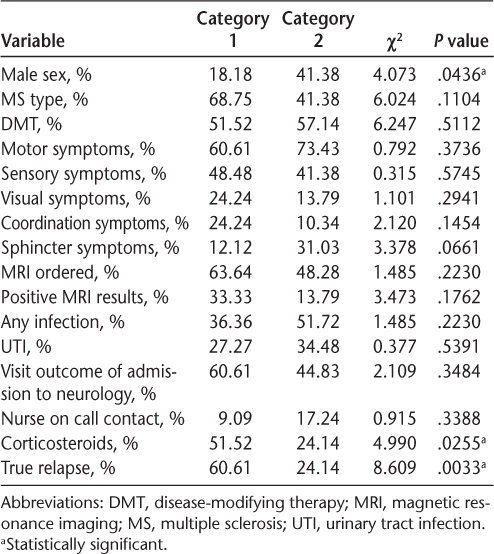

Table 3 shows the results of χ2 tests comparing categories 1 and 2 in relation to several categorical variables. As expected, category 1 visits were more likely to result from a true relapse compared with visits from category 2 visits (P = .0033) and, therefore, were more likely to be treated with corticosteroids (P = .025). Patients in category 1 were also more likely to be female compared with those in category 2 (P = .043). There was no statistically significant difference between the two categories in MS type, DMT use, presenting neurologic symptoms, number of MRIs ordered, presence of UTI, visit outcome, or use of nurse on call services before ED presentation. Category 1 visits had a higher percentage of positive MRI findings (33.3% of all category 1 visits and 52% of MRIs performed in this category) compared with category 2 (13.7% of all category 2 visits and 28% of MRIs performed in this category). However, the difference between the two groups in MRI positivity was not statistically significant.

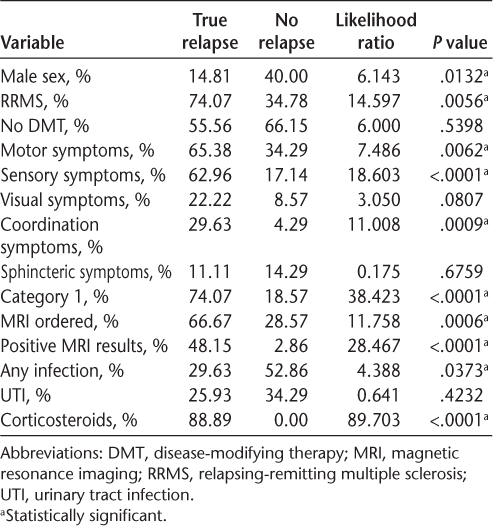

χ2 test comparing categories 1 and 2

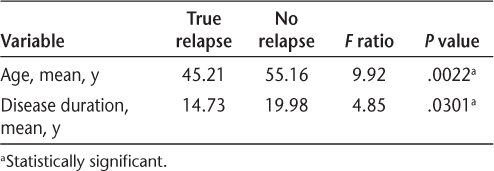

There were 27 visits in which a new relapse was determined (20 in category 1, seven in category 2, and zero in category 3) and 70 visits in which new relapse was excluded or not considered (13 in category 1, 22 in category 2, and 35 in category 3). Tables 4 and 5 show the results of t and χ2 tests, respectively, comparing visits in which a new MS relapse was determined (regardless of the visit category) with those in which new relapse was excluded (ED visits that were initially determined to be unrelated to MS were not included in this analysis). Visits with a new relapse were more likely to occur in younger patients with short disease duration, female patients, those with relapsing-remitting MS, and category 1 patients, especially those with new motor, sensory, or coordination deficits. They were more likely to undergo new MRI, to have positive findings on MRI, and to receive corticosteroids. They were less likely to have an associated infection. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in DMT use, visual or sphincteric presentation, and presence of UTI.

T test for continuous numerical variables by new relapse versus no relapse

χ2 Test for categorical variables by new relapse versus no relapse

Discussion

We studied ED visits of patients with MS over 1 year. We stratified ED visits based on the presenting symptoms into three categories: new neurologic, worsening of preexisting neurologic, and nonneurologic symptoms (categories 1, 2, and 3, respectively). The stratified categories differed significantly in the prevalence of new MS relapse, which was significantly more prevalent in patients in category 1.

When studying patients with new MS relapse as a group regardless of the visit category, they were more likely to be younger females with early relapsing-remitting disease. Indeed, they were more likely to belong to category 1, with new neurologic symptoms, especially motor, sensory, or coordination dysfunction, whereas visual and sphincteric symptoms were less specific for true relapse. The commonness of Uhthoff's phenomenon11 and UTIs in MS can probably explain why visual and sphincteric symptoms were less indicative of a true relapse.12 13 Although we expected sensory symptoms to also be less specific, the present data did not support this. The rates of DMT use and presence of UTIs were not different between visits with and without true relapses.

We found that more than one-third of patients presenting with new neurologic symptoms do not have a new MS relapse; rather, their new neurologic symptoms were attributed to a variety of other causes. Symptoms that are atypical for MS (seizures, painless vision loss, profound cognitive decline, etc.) should raise suspicion for alternative etiologies. Careful clinical examination of patients with MS presenting with atypical neurologic symptoms can reduce the number of unnecessary interventions (eg, vitreous hemorrhage on fundus examination, dermatologic manifestations of septic emboli).

In addition, a large number of patients presenting with new neurologic symptoms were found to have UTIs. Most of these patients presented with new sensory changes that were probably the result of previous asymptomatic relapses unmasked by UTIs. This possibility is supported by the absence of radiographic activity on MRI, the absence of other neurologic symptoms, and the improvement after antibiotic drug treatment seen in those patients. This reinforces the common practices of not treating pure sensory relapses in MS and checking urine in patients with new sensory symptoms even in the absence of urinary symptoms. However, it is important to note that visits with true relapse did not differ significantly from visits without true relapse in the prevalence of UTIs, and, therefore, a positive urinalysis finding in itself should not be considered a predictor of pseudorelapse, and each case should be evaluated individually.

The yield of obtaining a new MRI in patients with new neurologic symptoms was surprisingly low because only approximately 50% of MRIs ordered in this category showed evidence of radiographic disease activity. This underlines the importance of considering the patient's overall clinical findings before proceeding to MRI (eg, patients with new but mild sensory symptoms and positive urinalysis results should not undergo imaging). Note, however, that spinal MRI was not performed in every case, and, therefore, some radiologic activity may have been missed in this cohort. Moreover, most MRI studies were performed using a conventional 1.5-T magnet, which has low sensitivity to small and cortical lesions.

In category 2, patients who presented with worsening of preexisting neurologic symptoms had a significantly lower rate of true relapse with an expectedly low yield of new MRI compared with patients in category 1. Despite that, these categories did not differ in the number of MRIs ordered and the rate of neurology admissions; therefore, this group represents the highest need for quality improvement in ED triaging. Secondary causes should be presumed unless there is a quantifiable worsening in neurologic examination findings compared with previous documentations. A thorough search for secondary causes is crucial, and new neurologic diagnostic and therapeutic interventions should be kept to a minimum and for a few selected cases.

In category 3, patients with nonneurologic presentations were older, with longer disease duration and less use of DMTs. These visits were often handled appropriately without unnecessary interventions except for a small number of unnecessary neurology admissions.

It is important to note that the Cleveland Clinic is a high-volume center for patients with MS.14 The ED physicians and neurologists are well experienced with MS; therefore, the rates of unnecessary interventions presented in this study cannot be generalized to other centers. The true rates of unnecessary MRIs, corticosteroid treatments, and neurology admissions in the community may be substantially different from the numbers presented herein. This underlines the importance of establishing a unified triaging system for patients with MS in the ED because even in well-experienced high-volume centers, the rate of unnecessary interventions is still relatively high, at least in certain visit categories. In addition, there was a very low rate of telephone calls to the outpatient team or the nurse/resident on call before ED presentation in all visit categories. This highlights the importance of educating patients and providing them with easy accessibility to the treating team. Most patients who had no hospital needs and were, therefore, discharged from the ED could have been handled entirely over the telephone. The data captured in this study do not represent the patients who do call their outpatient team to report new symptoms/problems. Those patients, in our experience, rarely end up in the ED.

A well-implemented triaging system can reduce the cost of ED visits and subsequent hospital admissions significantly. In a study by Leary and colleagues,10 implementing a proactive case management system of patients with MS including general guidelines to the ED reduced hospital bed use by approximately 90%. Their study highlighted the strong effect of proper triaging of patients with MS on improving acute management. The role of MS nurse specialists in triaging patients seems to be pivotal in that process and should be used on a larger scale.15

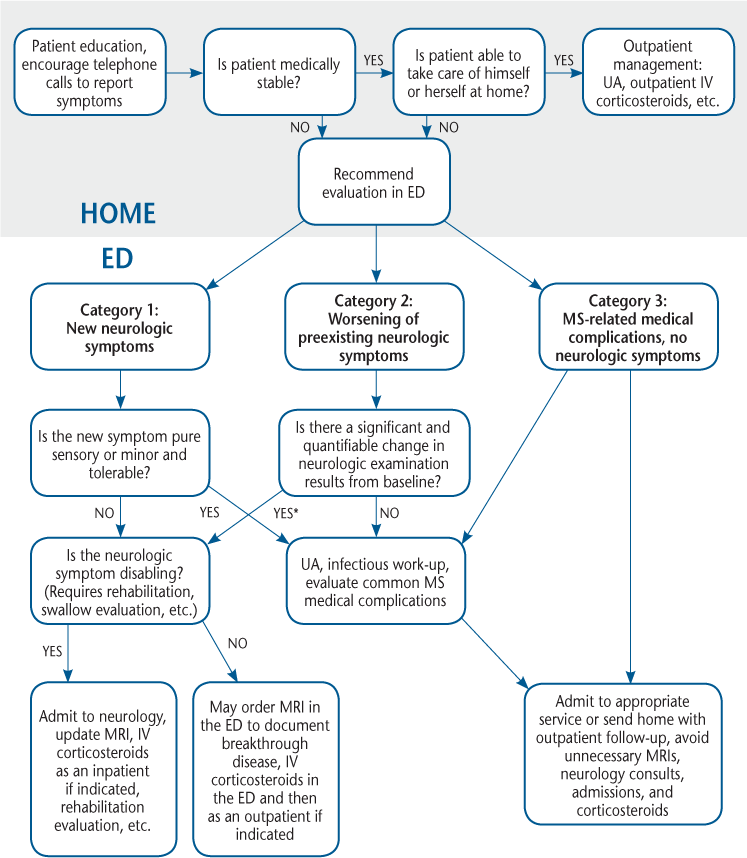

Areas for Improvement and Establishing a Triaging System

The following potential areas of improvement were identified for each group: for category 1 (new neurologic symptoms), there was a moderate number of unnecessary MRIs ordered; for category 2 (worsening neurologic symptoms), there was a significant number of unnecessary MRIs and neurology admissions; for category 3 (nonneurologic symptoms), there was a small number of unnecessary neurology admissions; and for all visit categories, there were few telephone calls made to the outpatient team before ED presentation. Based on these potential areas of improvement, we propose a simple triaging system for patients with MS at home and in the ED (Figure 1).

Algorithm for appropriate management of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) with new symptoms

Study Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the triaging system is based on patterns of mishandling patients in the ED, but it has not been tested for its utility or benefit. As a next step, we plan to gather post-implementation data to compare with the data presented herein to test whether the triaging system translates into practice improvement. Second, we did not analyze the actual cost of ED visits and subsequent hospital admissions. However, this study was meant to identify unnecessary interventions that can be eliminated when handling patients with MS in the ED and was not meant to be a comprehensive economic study. Studying the economic aspects of the ED triaging system is an important area for future research. Third, this study was based on medical record review, with its inherent documentation and reporting biases, which might have confounded the results.

Conclusion

A large number of unnecessary investigations and hospital admissions can be avoided in MS visits to the ED. A well-implemented triaging system for patients with MS in the ED based on symptom stratification has the potential for improving patient care and reducing unnecessary costs. This should be combined with efforts to reduce ED visits by encouraging telephone calls to the outpatient treatment team before ED presentation.

PracticePoints

Educating patients with MS and encouraging communication with the outpatient treatment team can reduce unnecessary visits to the emergency department (ED).

A triaging system based on symptom stratification may reduce unnecessary interventions and hospital admissions.

Patients presenting with new neurologic symptoms are more likely to have a new relapse than patients presenting with worsening of preexisting symptoms.

The prevalence of urinary tract infection (UTI) is the same in patients presenting with a new relapse and those without true relapse; therefore, the presence of UTI in itself should not determine the course of action taken in the ED.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Abboud receives honoraria from Genzyme Corp. Dr. Bermel receives fees as a paid consultant, speaker, or member of an advisory committee for Biogen Idec Inc, Genentech Inc, Genzyme Corp, Medscape, and Novartis International AG; and receives or has the right to receive royalty payments for inventions or discoveries commercialized through Biogen Idec Inc. Dr. Willis receives fees as a paid consultant, speaker, or member of an advisory committee for Biogen Idec Inc and Genzyme Corp. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Prescott JD, Factor S, Pill M, et al. Descriptive analysis of the direct medical costs of multiple sclerosis in 2004 using administrative claims in a large nationwide database. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13:44–52.

Maroney M, Hunter SF. Implications for multiple sclerosis in the era of the Affordable Care Act: a clinical overview. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(suppl 11):S220–S227.

Kobelt G, Berg J, Atherly D, Hadjimichael O. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study in the United States. Neurology. 2006;66:1696–1702.

Lad SP, Chapman CH, Vaninetti M, et al. Socioeconomic trends in hospitalization for multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;35:93–99.

Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA, Goldstein LB, Kulas ED. A comprehensive assessment of the cost of multiple sclerosis in the United States. Mult Scler. 1998;4:419–425.

Bourdette DN, Prochazka AV, Mitchell W, et al. Health care costs of veterans with multiple sclerosis: implications for the rehabilitation of MS. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:26–31.

O'Brien JA, Ward AJ, Patrick AR, Caro J. Cost of managing an episode of relapse in multiple sclerosis in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003;3:17.

Farber R, Hannigan C, Alcauskas M, Krieger S. Emergency department visits before the diagnosis of MS. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3:350–354.

Oynhausen S, Alcauskas M, Hannigan C, et al. Emergency medical care of multiple sclerosis patients: primary data from the Mount Sinai resource utilization in multiple sclerosis project. J Clin Neurol. 2014;10:216–221.

Leary A, Quinn D, Bowen A. Impact of proactive case management by multiple sclerosis specialist nurses on use of unscheduled care and emergency presentation in multiple sclerosis: a case study. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:159–163.

Perkin GD, Rose FC. Uhthoff's syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60:60–63.

Nikseresht A, Salehi H, Foroughi AA, Nazeri M. Association between urinary symptoms and urinary tract infection in patients with multiple sclerosis. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8:120–126.

Phé V, Pakzad M, Curtis C, et al. Urinary tract infections in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2016;22:855–861.

Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis. http://my.clevelandclinic.org/services/neurological_institute/mellen-center-multiple-sclerosis. Accessed March 30, 2016.

Quinn D, Bowen A, Leary A. The value of the multiple sclerosis specialist nurse with respect to prevention of unnecessary emergency admission. Mult Scler. 2014;20:1669–1670.