Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Fatigue and Mood States in Nursing Home and Nonambulatory Home-Based Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

Background:

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressively disabling condition of the central nervous system. We sought to evaluate and compare mood states in patients with MS with increased disability residing in nursing homes and those receiving home-based care.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium to identify patients with MS using a Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 7.0 or greater. The nursing home group was compared with home-based care patients regarding self-reported levels of loneliness, pessimism, tension, panic, irritation, morbid thoughts, feelings of guilt, and fatigue using independent-samples t tests and χ2 tests. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to investigate risk-adjusted differences in mood states.

Results:

Ninety-four of 924 patients with EDSS scores of at least 7.0 lived in a nursing home (10.2%). Nursing home patients were less likely to use disease-modifying therapy and had higher mean EDSS scores compared with home-based patients. However, nursing home patients were less likely than home-based patients to report fatigue (odds ratio [OR] for no fatigue, 3.8; 95% CI, 2.1–7.2), feeling tense (OR for no tension, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1–2.7), and having feelings of pessimism (OR for no pessimism, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2–2.8).

Conclusions:

The nursing home patients with MS were less likely to report fatigue, pessimism, and tension than those receiving home-based care. Further studies should examine ways of facilitating a greater degree of autonomy and decision-making control in MS patients receiving home-based care.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, immune-mediated demyelinating condition of the central nervous system. It usually affects young adults with various symptoms ranging from visual and motor limitations and bowel and bladder incontinence to cognitive dysfunction and psychological problems, such as depression1 and anxiety disorders,2 among others. Despite the great advances in management of the disease in the past 2 decades, irreversible disability in patients with MS still represents an unmet challenge with no efficacious therapeutic interventions available.3 4 Unfortunately, 30% of patients have been shown to require home-based care, of which 80% is reportedly provided by unpaid or informal caregivers, mostly family members.5 Home-based care can include personal assistance (eg, toileting and bathing), homemaking, aid in mobility and leisure activities,1 or symptom management (eg, administering corticosteroid injections and changing catheters during an episode of acute exacerbation of symptoms to avoid hospital admission).6

The need for this level of care demonstrates the social, psychological, and physical impact that MS can have on not only patients but also their families.7 In addition, the uncertainty of disease progression in MS can have implications for caregivers and social services. A study demonstrated that caregivers of patients with MS had a substantially lower quality of life (QOL) compared with healthy individuals and that a weak but significant correlation was present between the QOL of patients with MS and their caregivers.8 Although factors responsible for future nursing home placement still need to be understood, studies have shown that caregiver strain is one of the factors that can affect future nursing home placement, in addition to increasing age and functional decline.1

The nursing home placement of patients with MS has its own social implications in terms of higher cost of care compared with typical (elderly) nursing home residents. It has been shown that patients with MS, although more cognitively intact, are placed in nursing homes at a younger age than other residents and are more physically disabled, as measured by activities of daily living.9 There are few published data to suggest how patients with MS at upper disability levels fare emotionally in either setting. In light of the caregiver stress associated with home-based care, the high cost of institutionalization, and concern about the well-being of patients with MS residing in nursing home settings, evaluating the mood states of patients with MS in both these groups is warranted. The present study focuses on comparing the clinical and psychological characteristics of patients with MS with increased disability residing in nursing homes versus other patients with MS with similar levels of disability who were receiving home-based care.

Methods

Participants

Participants were part of the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium (NYSMSC). The NYSMSC was established in 1996 and currently comprises 12 MS centers throughout New York State, making it one of the largest and longest-lasting MS databases in the country, as described elsewhere.10 Informed consent was obtained from all the patients for inclusion in the study in compliance with institutional review board policies for research with human subjects. Inclusion criteria included patients with a Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of at least 7.0 who were extracted from the database. We selected this threshold because an EDSS score of at least 7.0 represents the point at which a person is no longer able to ambulate more than 3 m, with or without bilateral assistance, and is primarily wheelchair-bound. The final sample included 924 nonambulatory patients for analysis.

Questionnaire

The NYSMSC questionnaire collects information pertaining to demographic data and self-reported assessments at the time of a clinical visit, usually with yearly updates. The questionnaire is composed of one section completed by the patient and a second section of clinical data completed by the examining physician. At study enrollment, patients were asked about their living arrangement. Based on those responses, participants were categorized into either the nursing home group (referring to patients residing in a nursing home) or the home-based care group (referring to patients residing at home, with or without outside care). Patients were not recruited for participation if they reported a change of living situation within the past 6 months.

Participants were asked to rate their level of 1) loneliness, 2) pessimism, 3) tension, 4) panic, 5) irritation, 6) morbid thoughts, and 7) feelings of guilt on a scale from 1 (“none”) to 5 (“extremely”) by using the validated LIFEware system software (Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, Buffalo, NY).11 Furthermore, level of fatigue was measured on a scale from 1 (“no limitation”) to 7 (“severe limitation”). This questionnaire is completed at the time of the clinical visit corresponding to their last data available in the database. After careful examination of the data, a cutoff point was determined for the mood state variables to compare levels 1 and 2 (least affected) with levels 3 to 5 (most affected). Fatigue was categorized into three levels (no difficulties, some/moderate difficulties, moderate/severe difficulties) due to data distribution. Clinical data, such as MS type, exacerbation history, EDSS score, and information regarding disease-modifying therapy (DMT), were obtained from the physician evaluation.

Statistical Analyses

All the data were analyzed using a software program (IBM SPSS for Windows, version 21.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Demographic characteristics were compared between participants living in a nursing home to those living in a home-based care setting, using independent-samples t tests and χ2 tests. Variables that were significantly different between groups were considered potential confounders in subsequent analyses. Logistic regression analyses were used to investigate differences in mood states while adjusting for EDSS score, age at enrollment, marital status, sex, and DMT use.

Results

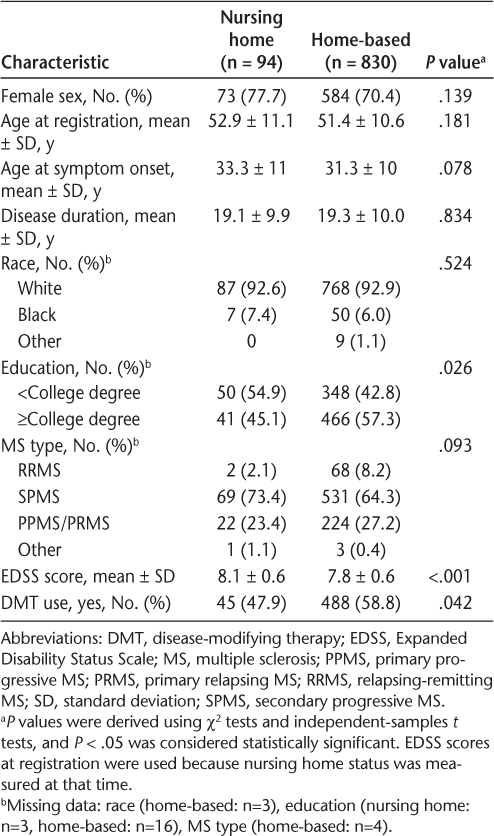

Of the 924 participants, 94 (10.2%) lived in a nursing home and 830 (89.8%) lived in a home-based care setting. There were no significant differences in sex, race, age at MS onset, or MS type between the groups (Table 1). There was a significant difference in educational levels (P = .026): nursing home patients were more likely to report less than a college level of education (54.9%) compared with patients receiving home-based care (42.8%, P = .026). The nursing home patients were also less likely to use a DMT compared with home-based patients (47.9% vs. 58.8%, P = .042). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in mean (SD) EDSS scores between the two groups (8.1 [0.6] for nursing home residents, 7.8 [0.6] for home-based patients, P < .001). These results are presented in Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of study participants

Another difference between the groups was the percentage of divorce. It has been reported that the divorce rate is higher in nursing home residents with MS versus other nursing home residents (22% vs. 9%).9 We found that the rate of divorce was higher in nursing home residents compared with patients receiving home-based care (41.8% vs. 21.5%, P < .001) in the present sample. Therefore, because divorce could also be a potential contributing factor (and, therefore, a confounder) toward feelings of pessimism and tension, we adjusted for marital status between the two groups and found that marital status did not significantly contribute to the model.

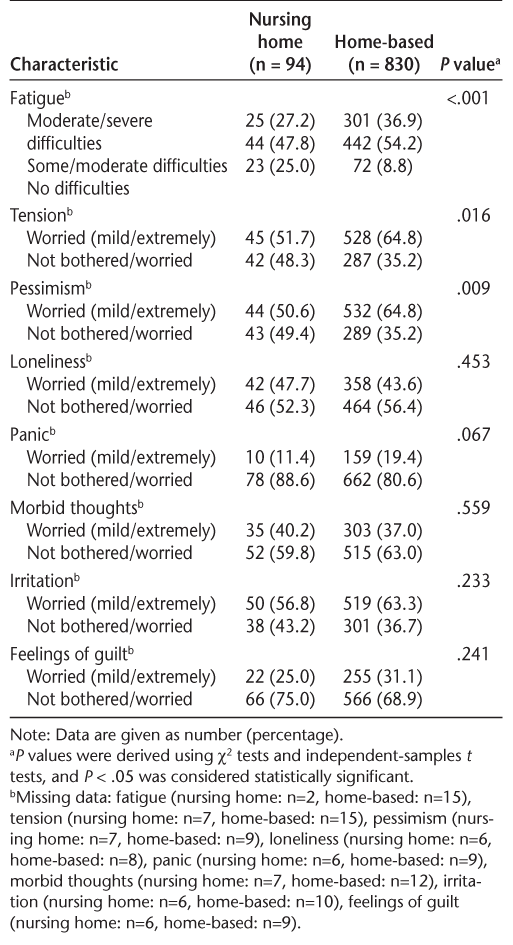

Nursing home patients reported moderate/severe levels of fatigue in 27.2% of the cases; this was significantly higher in patients receiving home-based care (36.9%, P < .001). Furthermore, just 51.7% of patients in the nursing home group reported feeling tense compared with 64.8% of patients receiving home-based care (P = .016). Similarly, 50.6% of patients in the nursing home group reported feelings of pessimism compared with 64.8% of patients in the home-based group (P = .009). There were no significant differences between the nursing home and home-based care groups for any of the other mood state variables, such as loneliness, feelings of panic, morbid thoughts, irritation, and feelings of guilt. These results are presented in Table 2.

Psychological characteristics of nursing home versus home-based care participants

Additional logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the association between living arrangement status and the significant LIFEware variables while adjusting for EDSS score, age, marital status, sex, and DMT use. Reporting a lack of pessimism (odds ratio [OR], 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1–2.8), a lack of tension (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.0–2.5), and no fatigue (OR, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.9–7.1) all remained significantly associated with living arrangement status in a nursing home in logistic regression analyses (Table 3). We stratified by EDSS score to examine the results for potential effect modification. When stratified by EDSS score (7.0–8.0 vs. >8.0), the results remained unchanged and statistically significant with respect to fatigue. For tension and pessimism, the results remained significant for those with an EDSS score of 7.0 to 8.0, which represented most of the sample (55 in nursing home group and 641 in home-based group).

Logistic regression results for association of fatigue, tension, and pessimism with being a nursing home resident

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, nursing home residents were found to be less likely to report fatigue, tension, and pessimism compared with patients receiving home-based care; no differences were found among other psychosocial or emotional characteristics. These results remained significant after adjusting for confounders. Furthermore, EDSS scores were higher and DMT use was lower for nursing home residents compared with patients receiving home-based care.

The present findings of lower prevalence of fatigue, pessimism, and tension experienced by nursing home residents, despite higher EDSS scores, might be indicative of their mental health, particularly because these symptoms can be caused, in part, by psychological problems such as depression and anxiety. The higher anxiety displayed by individuals with MS in the home-based care setting might reflect their fear about transitioning to nursing home care. However, the present results also provide evidence to support the finding that patients with MS benefit from skilled nursing services such as psychological counseling and physical and occupational therapies, which are more easily accessible in a nursing facility.9 12 Rehabilitation services, when available to nursing home residents with MS, as well as autonomy and decision-making control, when given to patients with MS despite their physical dependence, can have a strong influence on their QOL in a nursing home setting.13 14 Although we did not assess QOL or use of available rehabilitation services and, therefore, cannot come to any definitive conclusions, we suggest that this may also be part of the reason why we observed improved mood states in nursing home participants. In addition, psychological adjustment to MS has been linked strongly to a feeling of self-efficacy, which, in turn, is linked to self-esteem, depression, and self-worth.15 16 It is, therefore, possible that the care of a multidisciplinary team in a nursing facility gives patients with MS the mental satisfaction to be better equipped, which, in turn, may reduce tension and pessimism, as is reflected in this analysis.

Although there was a statistically significant difference in EDSS scores between nursing home patients and patients receiving home-based care, the actual clinical difference in disability between these groups is very low. It is possible that the lower level of fatigue reported by nursing home residents with MS reflects that these patients have to do less for themselves than patients receiving home-based care, despite being at similar disability levels. Unfortunately, we were limited in that we could not identify the reason for transitioning to nursing home care. However, because participants were not included if they reported a recent change in living status, we believe that it is unlikely that the reason behind transitioning to nursing home care would have biased the results in favor of nursing home residency. We did find that a significantly larger percentage of the participants in nursing home settings were divorced compared with those who remained in a home-based care setting. Although adjustment for this factor did not significantly alter the results, it may be that this factor contributes to determining which patients remain at home and which enter nursing homes.

Noyes et al.6 showed that although the cost for a skilled nursing facility is high, the staff-to-resident ratio is also high, leading to appropriate individualized care given to patients with MS and possibly resulting in a positive effect physically and psychologically. Interestingly, a study comparing daily costs incurred by skilled nursing facilities showed that there were no significant variations in daily cost for facilities with a greater proportion of patients with MS among their residents compared with those with fewer patients with MS.12 However, evidence suggests that most nursing home directors were unaware of the guidelines developed by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society to aid in the care of nursing home residents with MS.17 More specifically, these guidelines suggest that, at minimum, rehabilitation professionals should be available to residents with MS to “maximize independence, mobility, and quality of life.”18 It is conceivable, therefore, that an increase in awareness of these guidelines could further improve the quality of care that patients with MS residing in nursing homes receive.

Patients with MS receiving home-based care represent a complex situation. Associations have been documented between depression in older patients with MS and mental health–related QOL in their caregivers.7 Thus, higher levels of tension and pessimism in the present home-based care group, some of which is conceivably related to the fear of being moved to a nursing home away from their family,19 can translate to greater burden on their caregivers. Only 19.2% of people with a home-based living arrangement in the present sample lived alone; the rest lived with family, friends, or someone else who could potentially act as a caregiver or assist in daily tasks. A recent study showed high objective caregiver burden in informal caregivers, who spend approximately 6.5 hours per day caring for patients with MS. Objective and subjective burdens were positively correlated with higher EDSS scores.20

It has been documented in the literature that informal caregiving for patients with MS by family can be emotionally burdensome to caregivers.8 21 22 This may, in turn, influence changes in the patient's functioning.23 Caregiver depression has been significantly correlated with patients' emotional and physical health.23 Therefore, we speculate that the decrease in tension and pessimism observed in our nursing home group compared with the home-based group may, at least in part, result from not feeling as if they are a burden to family members. Thus, techniques to reduce caregiver stress would be of great utility. A recent study indicated that caregivers' emotional burden, engagement in health-promoting activities, and seeking help from the care-receiver's (ie, the MS patient's) health provider regarding self-care activities is associated with caregiver stress management.24 Furthermore, a clinical trial showed that a group psychoeducation program resulted in a significant reduction in family caregivers' burden immediately, as well as a month later, compared with the control group.25 Therefore, development and provision of such programs could prove to be beneficial to caregivers and, in turn, can also positively affect the quality of care provided by them. Ultimately, we hypothesize that it is likely that the burden of caregiving by informal caregivers, such as family and friends, affects the emotional status of the person with MS receiving home-based care and that more programs are needed to support caregivers in the home. Similarly, persons with MS who have had to transition to nursing home care often do quite well, and we speculate that they are likely to benefit from specialized rehabilitation services that can be provided to them.

Although the NYSMSC contains records of approximately 10,000 patients, a limitation of this study is the significantly lower number of nursing home residents compared with patients receiving home-based care. However, the proportion of patients residing in nursing home in the present study is similar to proportions reported in the literature.1 Although it is possible that there were limited visits of nursing home patients to the centers, generally we did not identify this as a concern. In our experience, difficulties with transportation are more often seen in disabled patients receiving home-based care. Therefore, to ensure that unequal sample sizes were not biasing the present results, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using a random sample of 94 individuals in the home-based group to equal the sample size in the nursing home group. There were no differences in the results; nursing home residents still reported less pessimism, tension, and fatigue than patients receiving home-based care in the smaller sample. We were unable to provide the exact duration the patient was in the nursing home, but patients were not recruited for participation if they reported a recent change in their living arrangement status (within the past 6 months).

Conclusion

This study showed that nursing home residents were less likely to report fatigue, pessimism, and tension compared with those receiving home-based care. Further studies should examine methods to facilitate a greater degree of autonomy and decision-making control in patients with MS receiving home-based care. Finally, efforts should be made to increase awareness of available guidelines designed for nursing homes to help in the care of residents with MS.

PracticePoints

Patients with MS residing in nursing homes report less fatigue, tension, and pessimism than patients with MS of similar disability levels residing at home with caregivers.

Practicing MS clinicians should emphasize to patients at appropriate disability levels that psychological counseling and the benefits of physical and occupational therapy are often more easily accessible in nursing facilities, and, for some, this may be an appropriate and desired option.

Future research should focus on stress-management interventions, or highlight those already readily accessible, for caregivers and home-based care patients with MS to reduce stress and increase autonomy and quality of life for both.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the investigators of the NYSMSC: Bianca Weinstock-Guttman, Robert Zivadinov, Channa Kolb, State University of New York–University at Buffalo and Jacobs Neurological Institute, Buffalo, NY; Andrew Goodman, Jessica F. Robb, University of Rochester, NY; Burk Jubelt, State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY; Allen Gerber, Albany Medical College, NY; Ilya Kister, Lauren Krupp, Lana Zhovtis Ryerson, New York University Langone Medical Center, NY; Patricia K. Coyle, Stony Brook University Medical Center, NY; Allan Perel, MS Comprehensive Care Center of Staten Island, Staten Island University Hospital, NY; Malcolm Gottesman, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY; Michael Lenihan, Adirondack Neurology, Glen Falls, NY; Keith Edwards, Lore Garten, MS Center of Northeastern NY, Latham, NY; and Mary Ann Picone, Holy Name MS Comprehensive Care Center, Teaneck, NJ.

References

Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Huang C, Zhu L. Caregiver perceptions associated with risk of nursing home admission for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Health J. 2010;3:117–124.

Ozcan ME, Ince B, Karadeli HH, Asil T. Multiple sclerosis presents with psychotic symptoms and coexists with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2014;2014:383108.

Khan F, Pallant J, Brand C. Caregiver strain and factors associated with caregiver self-efficacy and quality of life in a community cohort with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1241–1250.

Weinshenker BG, Bass B, Rice GP, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study, 2: predictive value of the early clinical course. Brain. 1989;112(pt 6):1419–1428.

Hillman L. Caregiving in multiple sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2013;24:619–627.

Noyes K, Bajorska A, Wasserman EB, Weinstock-Guttman B, Mukamel D. Transitions between SNF and home-based care in patients with multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;34:531–540.

Buhse M. Assessment of caregiver burden in families of persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;40:25–31.

Patti F, Amato MP, Battaglia MA, et al. Caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a multicentre Italian study. Mult Scler. 2007;13:412–419.

Buchanan RJ, Wang S, Ju H. Analyses of the minimum data set: comparisons of nursing home residents with multiple sclerosis to other nursing home residents. Mult Scler. 2002;8:512–522.

Jacobs LD, Wende KE, Brownscheidle CM, et al. A profile of multiple sclerosis: the New York State Multiple Sclerosis Consortium. Mult Scler. 1999;5:369–376.

Granger, CV. The LIFEwareSM System. J Rehabil Outcomes Meas. 1999;3:63–69.

Noyes K, Bajorska A, Weinstock-Guttman B, Mukamel DB. Is there extra cost of institutional care for MS patients? Mult Scler Int. 2013;2013:713627.

Mitchell AJ, Benito-Leon J, Gonzalez JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:556–566.

Riazi A, Bradshaw S, Playford E. Quality of life in the care home: a qualitative study of the perspectives of residents with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:2095–2102.

Barnwell AM, Kavanagh DJ. Prediction of psychological adjustment to multiple sclerosis. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:411–418.

Shnek ZM, Foley FW, LaRocca NG, et al. Helplessness, self-efficacy, cognitive distortions, and depression in multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:287–294.

Buchanan RJ, Seibert AL, Crudden A, Minden S. Assessments of nursing home guidelines for quality of care provided to residents with multiple sclerosis. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2013;12:237–255.

Northrop DE, Frankel D, eds. Nursing Home Care of Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis: Guidelines and Recommendations for Quality Care. New York, NY: National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2010.

Finlayson M. Concerns about the future among older adults with multiple sclerosis. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58:54–63.

Bayen E, Papeix C, Pradat-Diehl P, Lubetzki C, Joel ME. Patterns of objective and subjective burden of informal caregivers in multiple sclerosis. Behav Neurol. 2015;2015:648415.

Uccelli MM. The impact of multiple sclerosis on family members: a review of the literature. Neurdegener Dis Manag. 2014;4:177–185.

Pooyania S, Lobchuk M, Chernomas W, Marrie R. Examining the relationship between family caregivers' emotional states and ability to empathize with patients with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Int J MS Care. 2016;18:122–128.

Pozzilli C, Palmisano L, Mainero C, et al. Relationship between emotional distress in caregivers and health status in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10:442–446.

Penwell-Waines L, Goodworth MC, Casillas RS, Rahn R, Stepleman L. Perceptions of caregiver distress, health behaviors, and provider health-promoting communication and their relationship to stress management in MS caregivers. Health Commun. 2016;31:478–484.

Pahlavanzadeh S, Dalvi-Isfahani F, Alimohammadi N, Chitsaz A. The effect of group psycho-education program on the burden of family caregivers with multiple sclerosis patients in Isfahan in 2013–2014. Iran J Nurs Midwif Res. 2015;20:420–425.