Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Multiple Sclerosis Wellness Shared Medical Appointment Model

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Shared medical appointments (SMAs) are group medical visits combining medical care and patient education. We examined the impact of a wellness-focused pilot SMA in a large multiple sclerosis (MS) clinic.

Methods:

We reviewed data on all patients who participated in the SMA from January 2016 through June 2019. The following data were collected 12 months pre/post SMA visits: demographics, body mass index, patient-reported outcomes, and health care utilization. Data were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Results:

Fifty adult patients (mean ± SD age, 50.1 ± 12.3 years) attended at least one MS wellness SMA. Most patients had private insurance (50%), and 26% had Medicaid coverage. The most common comorbidity was depression/anxiety (44%). Pre/post SMA outcomes showed a small but significant reduction in body mass index (30.2 ± 7.3 vs 28.8 ± 7.1, P = .03), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores decreased from 7.3 ± 5.5 to 5.1 ± 5.6 (P = .001). The number of emergency department visits decreased from 13 to two (P = .0005), whereas follow-up visits increased with an attendees' primary care provider from 19 to 41 (P < .001), physical therapist from 15 to 27 (P = .004), and psychologist from six to 19 (P = .003).

Conclusions:

This pilot MS wellness SMA was associated with improved physical and psychological outcomes. There was increased, lower-cost health care utilization with reduced acute, high-cost health care utilization, suggesting that SMAs may be a cost-effective and beneficial method in caring for patients with MS.

Shared medical appointments (SMAs) are medical encounters in which multiple patients who share a common illness are seen simultaneously by one or more health care providers. These encounters are medical visits with an examination as well as group support and education. In contrast to an educational seminar, SMAs include clinical interventions, such as symptom management, and medication changes that are tailored to the needs of the group as well as the individual patients. They also provide a longer appointment time frame and the opportunity to share in peer-to-peer education and support compared with traditional office visits. Shared medical appointments have been shown to improve access, disease management outcomes, and patient-centered care.1–4

Shared medical appointments are most commonly used in primary care settings, but they have been explored in other subspecialties, including some surgical practices.5 This model has been studied in a limited number of chronic neurologic conditions, including neuromuscular disorders,6 Parkinson disease,7 and neuropathic pain.8 These pilot studies yielded mixed results but suggested that these visits improve patient-reported outcomes and physician productivity.

Given the complex clinical and psychological manifestations of multiple sclerosis (MS), we initiated a pilot MS SMA program focusing on wellness. Specifically, we wanted to examine the impact of a wellness-focused SMA on clinical outcomes. Even with the development of highly efficacious disease-modifying therapies, there is a need for overall wellness and comorbidity management in MS. For example, comorbid conditions are known to affect the clinical course of MS, including delaying time to diagnosis and reducing health-related quality of life.9 This makes the investigation of modifiable factors, such as comorbidities, important. The secondary question was whether SMAs shifted care to lower-cost but effective outpatient health care visits with reduced acute health care utilization, including emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions.

Methods

Participants

This retrospective study collected data from a clinical registry that included all the patients who participated in at least one MS wellness SMA visit from January 2016 through June 2019. Established patients in our center (Cleveland Clinic Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research) were invited to the SMA during routine clinical practice. Patients also continued to follow up with their providers while also attending the monthly SMAs to discuss more individual aspects of their care, including potential treatment changes, review of radiographic results, and updates regarding their general health. Patients were eligible to participate in the SMA if they were older than 18 years, had clinically definite MS,10 and had cognitive ability to consent to and participate in the activity. Information on patients who were referred to the SMA yet did not attend a session were not available in the electronic medical record (Epic Systems Corp). The SMA registry and subsequent analysis were approved by the Cleveland Clinic institutional review board.

Clinical Follow-up and Outcome Measures

The electronic medical record and MS performance testing data11 were reviewed for demographic information, health insurance status, MS disease history, Patient-Determined Disease Steps scale score, Timed 25-Foot Walk test time, dominant-hand Nine-Hole Peg Test time, employment history, comorbidities, body mass index (BMI), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores, and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) scores.

Health Care Utilization

To measure health care utilization, the following medical visits were analyzed over a 1-year period before and after a patient attended their first SMA session: primary care provider (PCP), physical therapist, occupational therapist, psychologist, and ED and hospital admissions based on previously published guidelines.12,13 The costs of the SMAs and the disease-modifying therapies were excluded because these were part of routine care for most patients and not the focus of this project. We defined acute health care utilization as any ED visits or hospital admissions and lower-cost health care utilization as outpatient services focused on MS care. This classification was based on previous research suggesting that acute care services are not optimized for patients with MS14 and could delay necessary treatment while also increasing overall cost for patients and health care systems.15,16 Our goal was to determine whether we could shift care toward outpatient services. A comprehensive economic review of MS care was outside the scope of this project.

SMA Intervention

The SMAs consisted of 1.5-hour sessions conducted monthly. The visits were jointly led by a physician, registered nurse, and medical assistant who addressed topics on brain health and MS symptom management to a group of five to 15 patients and their partners/caregivers. Each SMA also had a predetermined, variable experiential wellness intervention, including but not limited to demonstration cooking, nutritional consult, guided imagery, exercise, or chair yoga. After the introduction, the wellness topics were discussed and necessary prescriptions, referrals, and clinical documentation (including a limited neurologic examination) were also completed during the visit. In general, we avoided changes or modification to disease-modifying therapy or individual review of radiographic information because this can be difficult in a group setting. A comprehensive review of SMA operations is beyond the scope of this study but can be found in previously published studies.17–19

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics are summarized descriptively using proportions, means, and medians. Pre/post SMA data were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.6.0 (https://www.rproject.org). The significance threshold was set at P < .05.

Results

Demographics

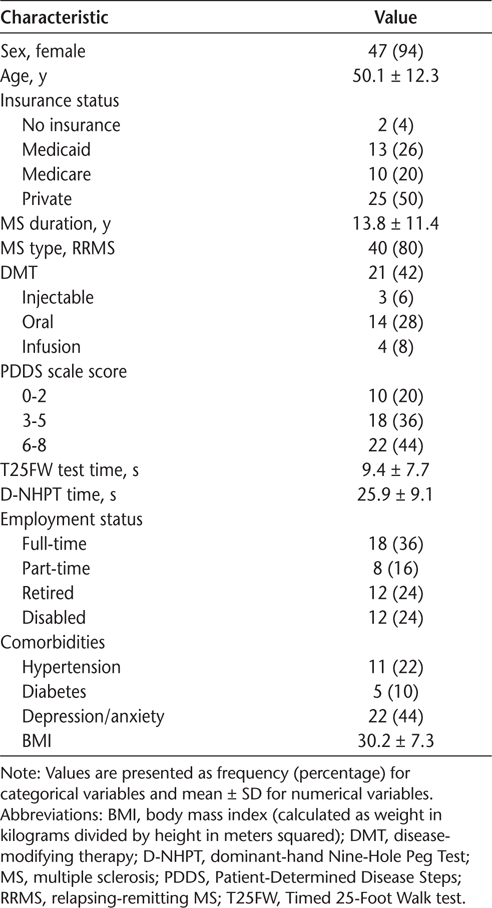

Fifty patients attended at least one SMA session, and 35 of them attended multiple sessions. All 50 patients had demographic and clinical information available for analysis (Table 1). The mean ± SD patient age was 50.1 ± 12.3 years, and most patients had relapsing-remitting MS. Approximately half of the patients were actively working (52%) and had private insurance (50%). Approximately a quarter were insured with Medicaid and 20% with Medicare. The mean MS disease duration was 13.8 ± 11.4 years, suggesting that there was a broad range of patients, including patients recently diagnosed as having MS. Depression and anxiety were the most common comorbidities, consistent with other MS cohorts.20

Demographic characteristics of the 50 study patients

Outcomes

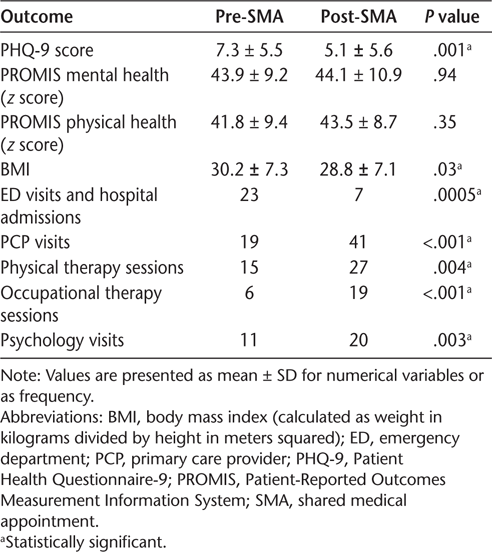

During the year after MS wellness SMA attendance, patients had improved mood, measured by mean ± SD PHQ-9 scores (7.3 ± 5.5 vs 5.1 ± 5.6, P = .001) with a trend toward improvement on the PROMIS mental (43.9 ± 9.2 vs 44.1 ± 10.9, P = .94) and physical (41.8 ± 9.4 vs 43.5 ± 8.7, P = .35) health scores, although those changes were not significant (Table 2). There was a reduction in mean ± SD BMI after SMA attendance (30.2 ± 7.3 vs 28.8 ± 7.1, P = .03).

Pre- and post-SMA outcomes

Heath Care Utilization

Attending an SMA decreased the number of treatment visits to acute care settings, including ED visits and hospital admissions (Table 2). A little more than a quarter of the present population (n = 13 [26%]) visited the ED in the year before the SMA, which was reduced to four patients (8%) in the year after the SMA. Most ED visits were for nonneurologic chief concerns (Figures S1 and S2, which are published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org). The most common neurologic chief concerns were sensory changes (67%), weakness (11%), and visual disturbance (11%). Among the nonneurologic chief concerns, gastrointestinal/genitourinary symptoms were the most common (17%), along with pain (15%) and febrile illnesses (12%). Outpatient visits to all provider types increased: PCPs, from 19 to 41 (P < .001); physical therapists, from 15 to 27 (P = .004); occupational therapists, from six to 19 (P < .001); and psychologists, from 11 to 20 (P = .003) (Table 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the use of an SMA in MS. In this pilot cohort, patients had improved psychological and physical outcomes even after attending a single SMA. In addition, SMA attendance shifted patient care from higher-cost, acute care settings to lower-cost, outpatient treatment environments. Based on these results, we posit that attending even a single MS wellness SMA has the potential to improve care for patients with MS.

The overall effectiveness of this MS wellness SMA could be attributed to the unique patient care approach. This multidisciplinary model focused on preventive health education and outpatient resources, complemented by the therapeutic benefit of group interactions. Evidence suggests that patients who actively participate in their care also better adhere to their treatment plans while reporting higher satisfaction with their providers.21 Shared medical appointments are specifically designed to encourage active participation, which is a likely component of their success. Note that the improved metrics could be related to the referrals generated from the SMA visits. For example, the improved PHQ-9 metrics may be related to the increased attendance with the behavioral medicine team. Overall, we are encouraged by the almost universal improvement in the metrics measured by this study, along with the utilization of MS-directed outpatient resources.

Shared medical appointments have been widely implemented in the primary care environment with varying success,4 whereas studies comparing the effectiveness of SMAs for patients with neurologic conditions are limited. Seesing et al6 showed improved patient-reported outcomes while improving the overall efficiency of their clinical workflow when implementing SMAs in a large neuromuscular department (n = 272). These results were also present even after attending just one SMA. When a similar protocol was implemented in a movement disorders clinic, there was no significant change in health outcomes, but the study population was relatively small (n = 30).7

Few studies have investigated health care utilization after SMA attendance. Select outcomes in diabetes22 and heart failure12 have been investigated, with reduced reliance on acute care treatment environments such as the ED being shown. Seesing et al6 also investigated health care utilization, and they showed no cost savings associated with their SMA but did show a significant reduction in the number of hospital admissions in the treatment group. Outcomes were investigated for only 6 months, so longer follow-up may have demonstrated more significant findings.

More attention has recently been placed on the high socioeconomic impact of MS.23,24 One strategy to combat the high economic burden of MS is to shift care away from acute care settings.25–27 Studies have shown that the initial diagnosis of MS might be delayed if patients initially present to an ED28 because services are not focused on MS care in that setting.14 One longitudinal study showed that in a 13-year period, the percentage of patients with MS admitted from the ED increased from 19.4% to 60.0%. The average cost per admission increased from $7965 in 1993 to $20,076 in 2006.15 The present SMA specifically highlighted the numerous outpatient services at our comprehensive MS center while encouraging regular appointments with PCPs. Consistent with previously published results, most visits to the ED were for nonneurologic chief concerns.16 This observation highlights the importance for patients to have established PCPs, which was routinely discussed in the SMAs in the present study. Although acute care management for MS is appropriate at times, proactive management through a partnership of patients, caregivers, and PCPs is vital for the long-term care of patients with MS.14,29

The present study and its findings are limited by inclusion of a small, relatively homogenous population. The retrospective analysis without a comparison group is another limiting factor. We attempted to identify individuals who were referred to the SMA program yet did not attend a session as a control group, but this information was not available in the electronic medical record. We also did not account for the variable wellness topics discussed in each session, which may have confounded the results. That being said, general health practices that are important in MS care are discussed in each session, limiting the variability among sessions.

We considered and analyzed specific encounters within our institution only, although it is fair to assume that most of the attendees lived locally and received most of their care within our large health system because SMAs are hosted monthly. The economic estimates were also limited in scope and did not include radiologic studies, pharmaceuticals, or other health care visits. The goal was to determine whether we could shift care toward services more oriented toward patients with MS rather than a comprehensive economic review of MS care. Also note that the Cleveland Clinic is a high-volume MS center with caregivers who are very familiar with MS. Therefore, some of the findings presented in this study may not be generalizable to other health systems. Finally, survey data related to the experience/satisfaction of the SMA, which would have complemented the present findings, were not incorporated into this study because we did not have consistent access to those data. Future longitudinal, prospective studies are needed to investigate whether SMAs can effectively deliver superior care to patients with neurologic disorders. In addition, further research is needed to optimize SMA use in patients with MS.

Shared medical appointments have been shown to be an effective treatment model for chronic conditions, but there is limited experience with their use in neurologic disorders. The present small pilot MS wellness SMA program has been shown to be a feasible and possibly low-cost care model for MS.

PRACTICE POINTS

Shared medical appointments (SMAs) are effective treatment models for chronic conditions, but there is limited evidence for their use in neurologic disorders.

This pilot SMA program for patients with MS demonstrated improved psychological and physical outcomes for patients even after attending a single SMA.

Attendance at SMAs shifted patient care from high-cost, acute care settings to outpatient treatment centers, suggesting that MS SMAs are a cost-effective method to improve care for patients with MS.

Financial Disclosures

Dr Cohen has received personal compensation for consulting from Adamas, Convelo, MedDay, Mylan, and the Population Council and serves as an Editor of Multiple Sclerosis Journal. Dr Udeh receives commercial research support from Teva. Dr Rensel serves on the advisory boards or panels of Serono and Biogen; serves as a consultant to Biogen, Teva, Genzyme, and Novartis; receives grants/research support from MedImmune, Novartis, Genentech, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and Genzyme; and serves on the speakers' bureaus of Novartis, Genzyme, Biogen, and the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Bronson DL, Maxwell RA. Shared medical appointments: increasing patient access without increasing physician hours. Cleve Clin J Med . 2004; 71: 369– 370, 372, 374 passim.

Clancy DE, Brown SB, Magruder KM, Huang P. Group visits in medically and economically disadvantaged patients with type 2 diabetes and their relationships to clinical outcomes. Top Health Inf Manage . 2003; 24: 8– 14.

Stults CD, McCuistion MH, Frosch DL, Hung DY, Cheng PH, Tai-Seale M. Shared medical appointments: a promising innovation to improve patient engagement and ease the primary care provider shortage. Popul Health Manag . 2016; 19: 11– 16.

Burke RE, O'Grady ET. Group visits hold great potential for improving diabetes care and outcomes, but best practices must be developed. Health Aff (Millwood) . 2012; 31: 103– 109.

Wong AL, Martin J, Wong MJ, Bezuhly M, Tang D. Shared medical appointments as a new model for carpal tunnel surgery consultation: a randomized clinical trial. Plast Surg (Oakv) . 2016; 24: 107– 111.

Seesing FM, Drost G, Groenewoud J, van der Wilt GJ, van Engelen BG. Shared medical appointments improve QOL in neuromuscular patients: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology . 2014; 83: 240– 246.

Dorsey ER, Deuel LM, Beck CA, et al. Group patient visits for Parkinson disease: a randomized feasibility trial. Neurology . 2011; 76: 1542– 1547.

Romanelli RJ, Dolginsky M, Byakina Y, Bronstein D, Wilson S. A shared medical appointment on the benefits and risks of opioids is associated with improved patient confidence in managing chronic pain. J Patient Exp . 2017; 4: 144– 151.

Briggs FBS, Thompson NR, Conway DS. Prognostic factors of disability in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord . 2019; 30: 9– 16.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol . 2011; 69: 292– 302.

Rudick RA, Miller D, Bethoux F, et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Performance Test (MSPT): an iPad-based disability assessment tool. J Vis Exp . June 30, 2014: e51318.

Lin A, Cavendish J, Boren D, Ofstad T, Seidensticker D. A pilot study: reports of benefits from a 6-month, multidisciplinary, shared medical appointment approach for heart failure patients. Mil Med . 2008; 173: 1210– 1213.

Scott JC, Conner DA, Venohr I, et al. Effectiveness of a group outpatient visit model for chronically ill older health maintenance organization members: a 2-year randomized trial of the cooperative health care clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc . 2004; 52: 1463– 1470.

Abboud H, Mente K, Seay M, et al. Triaging patients with multiple sclerosis in the emergency department: room for improvement. Int J MS Care . 2017; 19: 290– 296.

Lad SP, Chapman CH, Vaninetti M, Steinman L, Green A, Boakye M. Socioeconomic trends in hospitalization for multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology . 2010; 35: 93– 99.

Oynhausen S, Alcauskas M, Hannigan C, et al. Emergency medical care of multiple sclerosis patients: primary data from the Mount Sinai Resource Utilization in Multiple Sclerosis project. J Clin Neurol . 2014; 10: 216– 221.

Berger-Fiffy J. The “nuts and bolts” of implementing shared medical appointments: the Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates experience. J Ambul Care Manage . 2012; 35: 247– 256.

Kirsh SR, Aron DC, Johnson KD, et al. A realist review of shared medical appointments: how, for whom, and under what circumstances do they work? BMC Health Serv Res . 2017; 17: 113.

McCuistion MH, Stults CD, Dohan D, Frosch DL, Hung DY, Tai-Seale M. Overcoming challenges to adoption of shared medical appointments. Popul Health Manag . 2014; 17: 100– 105.

Marrie RA. Comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: implications for patient care. Nat Rev Neurol . 2017; 13: 375– 382.

Holman H, Lorig K. Patients as partners in managing chronic disease: partnership is a prerequisite for effective and efficient health care. BMJ . 2000; 320: 526– 527.

Clancy DE, Dismuke CE, Magruder KM, Simpson KN, Bradford D. Do diabetes group visits lead to lower medical care charges? Am J Manag Care . 2008; 14: 39– 44.

Sicras-Mainar A, Ruiz-Beato E, Navarro-Artieda R, Maurino J. Impact on healthcare resource utilization of multiple sclerosis in Spain. BMC Health Serv Res . 2017; 17: 854.

Adelman G, Rane SG, Villa KF. The cost burden of multiple sclerosis in the United States: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Econ . 2013; 16: 639– 647.

Naci H, Fleurence R, Birt J, Duhig A. Economic burden of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics . 2010; 28: 363– 379.

Fogarty E, Walsh C, McGuigan C, Tubridy N, Barry M. Direct and indirect economic consequences of multiple sclerosis in Ireland. Appl Health Econ Health Policy . 2014; 12: 635– 645.

Kobelt G, Berg J, Atherly D, Hadjimichael O. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study in the United States. Neurology . 2006; 66: 1696– 1702.

Farber R, Hannigan C, Alcauskas M, Krieger S. Emergency department visits before the diagnosis of MS. Mult Scler Relat Disord . 2014; 3: 350– 354.

Leary A, Quinn D, Bowen A. Impact of proactive case management by multiple sclerosis specialist nurses on use of unscheduled care and emergency presentation in multiple sclerosis: a case study. Int J MS Care . 2015; 17: 159– 163.