Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Multiple Sclerosis at Home Access (MAHA)

Abstract

Background:

Caring for individuals with progressive, disabling forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) presents ongoing, complex challenges in health care delivery, especially access to care. Although mobility limitations represent a major hurdle to accessing comprehensive and coordinated care, fragmentation in current models of health care delivery magnify the problem. Importantly, individuals with disabling forms of MS are exceedingly likely to develop preventable secondary complications and to incur significant suffering and increased health care utilization and costs.

Methods:

A house call program, Multiple Sclerosis at Home Access (MAHA), was implemented. The program was designed to provide comprehensive services and prevent common complications. Key aspects included monthly house calls, continuity among providers, and a multidisciplinary team led by a comprehensivist, a provider bridging subspecialty and primary care. A total of 21 adult patients (Expanded Disability Status Scale score ≥7.5) completed 1 full year of the program.

Results:

During the 2-year preevaluation and postevaluation period, half of the hospital admissions were related to secondary and generally preventable complications. Aside from a single outlying individual important to the evaluation, in the year after program implementation, decreases were found in number of individuals hospitalized, hospitalizations/skilled facility admissions, and hospital days; the total number of overall emergency department (ED) visits decreased; and ED-only visits increased (ie, ED visits without hospital admission). Patient satisfaction reports and quality indicators were positive. Fifty percent of patients participated in supplementary televisits.

Conclusions:

This program evaluation suggests that a house call–based practice is a viable solution for improving care delivery for patients with advanced MS and disability.

Despite advances in treating relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), many individuals have, or will enter, a progressive phase of disease. A 2006 study highlighted substantial-to-profound disability in more than one-third of individuals with MS and indicated that 36% of individuals with MS were using assistive walking devices.1 A recent estimate of the overall prevalence of MS in the United States totaled more than 1 million individuals, more than twice that of previous reports,2 in part suggesting an increasing number of aging individuals likely with progressive forms of MS.

Although specific problems and disease progression vary, most individuals with progressive, disabling forms of MS have limitations in mobility, upper body movement, coordination, bladder and bowel function, vision, speech, swallowing, and respiratory musculature. More than half have physical pain.3 Cognitive dysfunction and depressive mood disorders are prevalent. With increasing disability, patient-reported health-related quality of life decreases.4 The emotional toll of progressive MS is evident in a strategic National MS Society white paper report. Individuals reported feeling “disconnected,” “underserved,” “isolated,” and “forgotten.” Still, most desired to remain at home when possible, acknowledging the overwhelming impact of the disease on their family.5 Consequently, family members are likely to experience caregiver burden, mood disorders, and strain on their health.6 The progressive phase of MS clearly meets the criteria of a complex specialty illness, as outlined by the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model,7 and suggests the need for new models of care delivery.

The dynamic, highly complex, and disabling phase of progressive MS presents extensive challenges in essentially all aspects of health care delivery, especially access to care. Although limitations in mobility represent a major hurdle to accessing comprehensive and coordinated health care,8 fragmentation in current models of health care delivery, along with societal limitations such as lack of accessible transportation, magnify the problem. Individuals with progressive forms of MS and disability are exceedingly likely to develop generally preventable complications and comorbidities, along with significantly increased health care utilization and costs.9 In addition, there is an impetus to avoid hospitalizations in neurologically disabled individuals, as cited in a report finding that nearly 40% experienced adverse events related to hospitalization.10

A recent review detailed deficiencies in all phases of access to MS care for those with disability.11 Before clinic visits, patients with MS reported difficulties with insurance, referrals, and making appointments, along with repeated reports of lack of and/or inadequate transportation services. During clinic visits, patients reported poor accessibility, including inadequate handicap parking at provider offices, lack of and/or inadequate equipment at examinations, insufficient time with providers, providers' inadequate MS education, poor communication, and lack of general care. Postvisit issues included difficulty connecting with referrals and lack of follow-up. Given these documented obstacles, an alternative model of care addressing existing deficiencies is expected to improve accessibility to health care, overall satisfaction, and outcomes for homebound individuals living with MS.

In spring 2014, to address the important obstacles and limitations in health care delivery for individuals with advanced MS, we implemented a home-based, patient-centered, comprehensive house call program: Multiple Sclerosis at Home Access (MAHA). This program was designed to provide a full range of services for patients and their caregivers in their homes and communities. This report represents an initial evaluation of the MAHA initiative, including measures of selected clinical quality outcomes, processes, results, and collection of ongoing information.

Methods

The MAHA Program

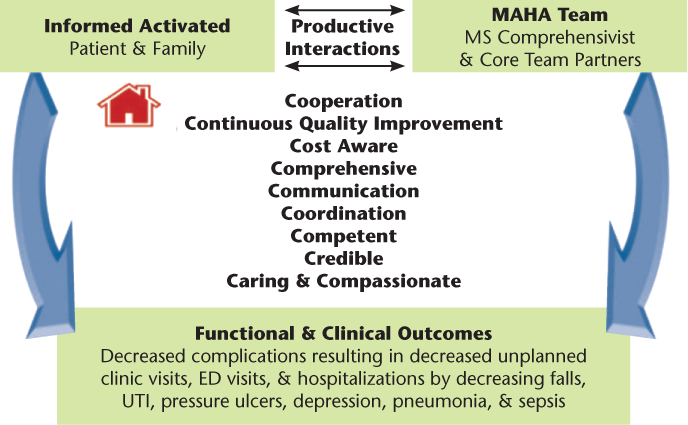

The conceptual framework and fundamental principles specified for the house call program MAHA were adapted and further modified12 from Wagner's chronic care model (the six parts of which are community [resources and policies], health system [organization of health care], self-management support, delivery system, decision support, and clinical information systems)13 and the PCMH model.7 The structure, process, and guiding concepts of MAHA were developed in a simple, understandable manner such that all team members had insight into the development and implementation of overall plans of care. In doing so, we developed a prototype for an innovative and practical model focused on high-quality, comprehensive, patient-centered care with the goal of preventing common complications. The guiding principles of the MAHA care process feature ten central elements, or “the 10 C's” (Figure 1). By operationalizing and implementing these elements, productive interactions and positive outcomes were expected.

Conceptual framework

The MAHA house call program derived its name from its city of origin, Omaha, Nebraska. This region was first settled by the Maha Native American tribe, and maha means “against the wind, against the current.” This word and meaning seemed to capture the struggles of patients with MS and their families trying to access comprehensive quality care.

The objectives of the MAHA program were to coordinate and deliver comprehensive medical care in the home, improve patient satisfaction, and prevent or treat common complications related to immobility, with an expected resultant decrease in preventable/avoidable health care utilization. The MAHA model was designed to focus on transforming health care for patients with severe disability in their homes and communities. The future, long-term goals of the program were to improve quality of life, promote wellness, increase independence, and promote community reintegration.

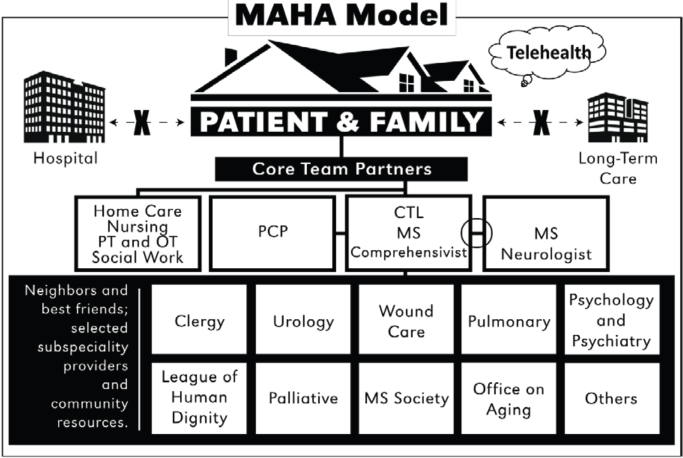

The structure of the MAHA program (Figure 2) included multidisciplinary core team partners, composed of care providers who maintained ongoing hands-on care and frequent home visits, with the intent of fostering trusting relationships between patients, families, and providers. Core team partners included a house call provider, a nurse practitioner (NP), a medical assistant, personal caregivers (including family), and, generally, a skilled home health care team that included nursing and physical/occupational therapists. A unique expanded role of the house call provider, termed the MS comprehensivist, was also developed. This individual was a provider with prescriptive privileges, subspecialty training in MS, and primary care experience managing patients with chronic illness. The comprehensivist served as an integrator, implementing the co-management concept in the PCMH model and bridging primary and subspecialty care, and functioned as the care team leader.

Multiple Sclerosis at Home Access (MAHA) model

Because most patients with MS required skilled nursing and physical therapy, a preferred home health care agency willing to commit to specialized education, competency, and continuity was identified and offered to patients. However, ultimately, patients or insurers determined the agency. Best friends were trusted community specialists who demonstrated competence, interest, and concern for individuals with disability, and included urologists, ophthalmologists, dentists, pulmonologists, mental health professionals, and wound specialists. Neighbors were community entities that assisted with necessary resources and support, such as the League of Human Dignity, the Office on Aging, Paralyzed Veterans of America, the Multiple Sclerosis Foundation, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Patients were referred to the program by neurologists, primary care physicians (PCPs), or self-referral. Patients living within a 60-mile radius of the MS Clinic at Nebraska Medicine in Omaha were offered the program, with the ongoing option to return to traditional clinic care. Program eligibility included a diagnosis of MS or neuromyelitis optica, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)14 scores of 7.5 or greater, and significant difficulty leaving their homes, thus meeting the criteria for homebound status. Patients with preexisting complications (eg, decubitus/pressure ulcers) were accepted. The PCPs were contacted and agreed to the co-management structure.

House calls were performed by the NP and medical assistant at least monthly for the first 6 months. Home care team members made visits at least twice weekly, and as needed, and skilled needs continued (ie, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and nursing). If the agreed-on goals of care were reached, house call visits decreased to every other month and were supplemented with secured televisits as appropriate. Monthly house calls continued for those with active care issues. When patients reached agreed-on goals of care (ie, had knowledge and resources to prevent common complications), had reliable transportation, and had less difficulty getting to clinic appointments, patients were graduated from the program and resumed traditional clinic care.

The initial visit(s) included a comprehensive assessment, including complete medical/social history, medication management, activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental ADLs, MS functional systems and EDSS, and review of durable medical/assistive home safety devices. Mutually identified goals of the program, including staying in their home versus a facility and for preventing common complications and other unique patient goals, were identified, confirmed, and reviewed at subsequent visits. Each house call generally lasted 1 to 2.5 hours and was billed based on face-to-face time. In addition to the NP's role in prescribing medication, developing treatment protocols, and evaluating medical equipment needs, much time was spent on point-of-service activities generally consisting of coordination, education, counseling, and communication of the plan of care, thus supporting the productive interaction and integration of services essential to the model.

To facilitate communication, weekly care plan oversight conferences were held among the core team partners, including home health care service providers (eg, physical therapists and nurses), personal assistance providers, and the medical assistant. Visit summaries, including the plan of care, were sent to patient and family, PCP, MS neurologist, and core team partners.

Documentation of clinical outcomes (ie, continuous quality improvement), referred to as the report card, was completed weekly. Information on falls, infections, skin breakdown, unplanned clinic/emergency department (ED) visits, and hospitalizations was monitored, recorded, and analyzed; care plans were modified accordingly. Practice guidelines and educational material identified to direct care included information from Paralyzed Veterans of America, the Kessler Foundation, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. If guidelines were proving ineffective, the patient's PCP or specialty MS neurologist provided advice on alternative care directions. Educational material provided for patients, family, and personal care assistants included information on spinal cord injury, targeting prevention of common complications of those with advanced disability.

Because this initiative was a clinical demonstration project as part of clinical care and quality improvement, and not considered human subjects research, institutional review board review was waived.

Clinical Outcome Measures

Based on evidence that a substantial portion of health care utilization by individuals with significant disability was likely due to preventable complications, data on ED visits, inpatient stays, admissions to skilled nursing facilities, lengths of stay (LOSs), and discharge diagnoses were collected 1 year before and 1 year after program initiation. Discharge diagnoses were categorized under preventable conditions (eg, infections, falls and injury, pressure/decubitus ulcer), relapses, and other. Selected quality process indicators, including pneumovax vaccinations, annual flu shots, advanced directives, and assignment of medical power of attorney, were collected from medical records and review of charts (our facility and others) and were confirmed with patients and family members.

Evaluation of Patient Satisfaction

To assess patient satisfaction with the program, an eight-item, unidimensional, self-administered survey with no identifying information was used. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (maximal).15 Additional open-format items were included. Surveys were given during the house call visit 3 to 6 months after entering the program.

Statistical Analysis

Due to the limited number of individuals enrolled, the program's intent, and the level of inquiry (ie, iterative and program evaluation), we used nonparametric descriptive statistics and qualitative reporting.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

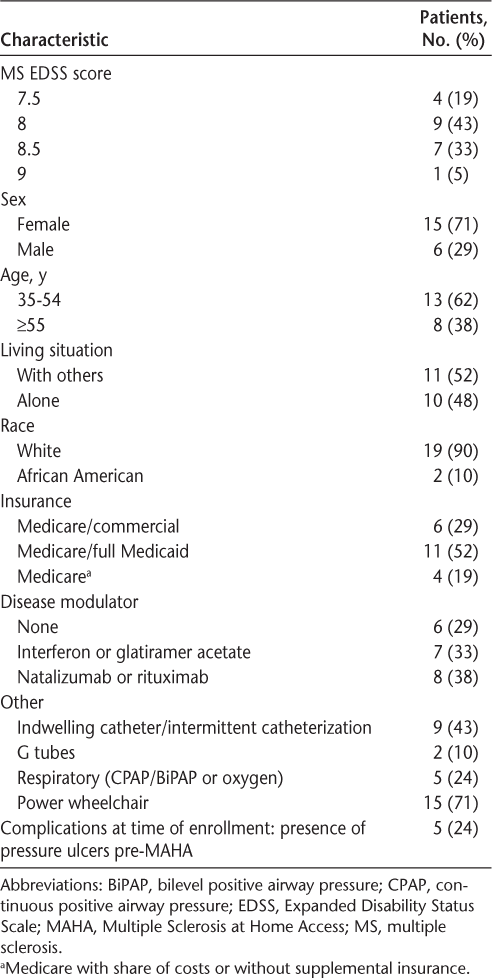

The MAHA program began in February 2014; as of January 2017, 28 patients living in the community were enrolled, and 21 completed at least 1 year of the program. Of the 28 enrolled, seven patients did not complete the full year due to placement in a long-term care facility (n = 1), inability to comply with program requirements (n = 2), discharge from the program (eg, no longer met eligibility requirements of homebound) (n = 1), and death (n = 3). Table 1 provides the baseline characteristics of the 21 patients enrolled in the program for at least 1 year. Fifteen patients (71%) were women, 13 patients (62%) were younger than 55 years, and nearly half lived alone. All the participants were enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, or both, and 11 (52%) were Medicare/full Medicaid waiver eligible, with income equal to or below the federal poverty level. More than two-thirds of the participants used power mobility wheelchairs associated with upper extremity dysfunction. Seven patients either had swallow dysfunction and used a gastric tube or needed respiratory support (continuous positive airway pressure/bilevel positive airway pressure). On enrollment in the program, five patients had varying stages and sizes of pressure/decubitus ulcers.

Baseline characteristics of 21 patients enrolled in MAHA program for at least 1 year

During the combined pre- and post-MAHA 2-year period, one-half of all hospitalizations and 116 hospital days were related to potentially preventable complications of immobility and disability (ie, urinary tract or respiratory tract infections, falls, or pressure/decubitus ulcers) (Table 2). Decubitus ulcers and respiratory tract infections accounted for the largest number of hospital days: 62 and 36, respectively.

Hospitalizations and LOS per discharge diagnosis

When evaluating pre- and post-MAHA outcomes with respect to urinary and respiratory tract infections, the number of patients, number of admissions, and hospital LOS improved post-MAHA. However, pressure ulcer admissions to the hospital increased, largely because one patient had three admissions for this decubitus/pressure ulcer diagnosis, with a combined total hospital LOS of 48 days; this individual was considered an outlier as defined by medical care organizations.16 One additional patient was electively admitted overnight for a skin grafting procedure. Importantly, both individuals had pressure ulcers on admission to the program. Table 3 provides summary statistics for ED visits (with and without resultant hospital admission), along with data for hospitalizations, and skilled nursing facility stays for the 12 months pre- and post-MAHA enrollment. Data are presented with and without the outlier.

Summary statistics for ED visits, hospitalizations, and skilled nursing facility stays

Ten of the 21 patients were admitted to the hospital at least once during the year before program initiation compared with eight individuals the year after program initiation. The number of patients with two or more admissions to the hospital also decreased from four pre-MAHA to two post-MAHA. The number of patients admitted through the ED (without hospitalization) increased from two pre-MAHA to five post-MAHA. Total hospital admissions decreased from 14 pre-MAHA to 11 post-MAHA. Omitting utilization of data for the single outlying individual, who had three admissions (through the ED) for a preexisting pressure/decubitus ulcer, hospital admissions decreased from 14 pre-MAHA to 8 post-MAHA. With the outlying individual included, total hospital LOS increased from 80 days pre-MAHA to 85 days post-MAHA; excluding outlier data, a decrease from 80 to 37 days was seen in hospital LOS. The number of skilled nursing facility admissions also decreased during the post-MAHA period compared with the previous year, from 12 to 6 with the outlying individual included and from 12 to 4 with the outlier data excluded. Without the outlier data (n = 20), decreases in total skilled nursing facility admissions and days reached or nearly reached significance (P = .09 and .02, respectively). In addition, the proportion of patients with at least one skilled nursing facility admission was significantly less during the 12-month period after MAHA implementation (45% vs 15%; P = .03).

Selected process quality indicators, including vaccination rates, documentation of advanced directives, and medical power of attorney, improved during the post-MAHA period. Seven patients had been vaccinated for pneumonia before program initiation and 17 after program initiation, with 81% of patients vaccinated for pneumonia with either 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine or 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, comparing favorably with a statewide average of 62.7%. During the 2015–2016 influenza season, all 21 patients enrolled in the program were offered the influenza vaccine: four (19%) refused and 17 (81%) accepted, comparing favorably with the national vaccination rate of 63.4% for Medicare beneficiaries. Before program initiation, only 7 patients (33%) had documented medical power of attorney and advanced directives compared with 14 (67%) after implementation.

A total of 16 satisfaction surveys were returned by the 21 patients; the eight-item questionnaire, with a total score of 32 being the highest possible satisfaction, revealed a mean score of 30. Comments about the program generally reflected benefits, for example, “The program was very helpful for me” and “It was a Godsend.”

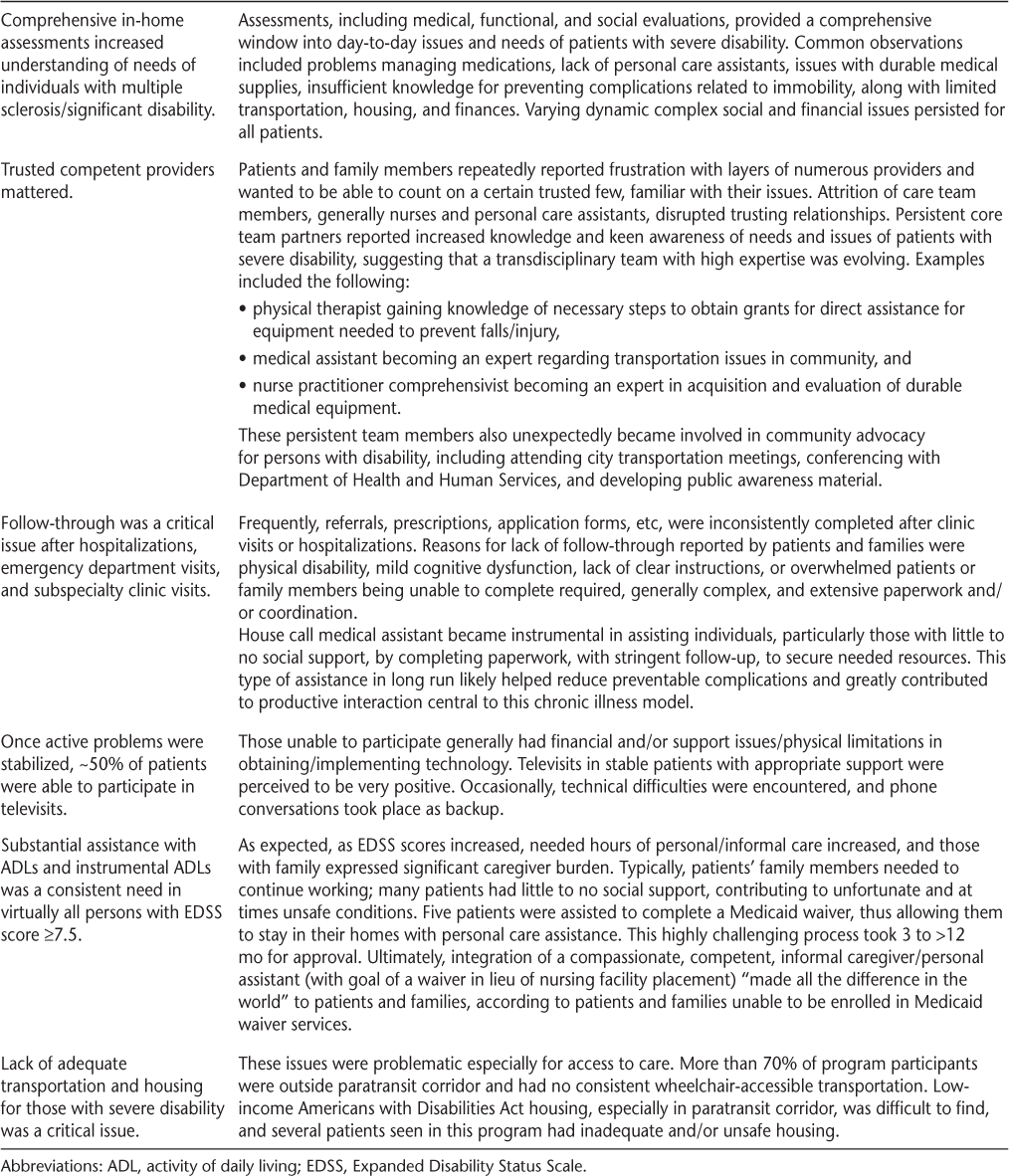

Lessons Learned

Table 4 includes common themes, lessons learned, and insights that emerged over the first year of operation, identified by patients, family members, and providers. Key findings included benefits of assessments in homes, importance of clinical expertise and continuity of care, close follow-up, need for greater assistance with ADLs, benefits of supplemental televisits, and greater awareness of societal limitations for the disabled, including transportation and housing.

Lessons learned

Discussion

The dynamic, complex, and disabling phase of progressive MS presents extensive challenges in essentially all aspects of health care delivery, especially care access. We developed and implemented a comprehensive house call program (ie, MAHA) to coordinate and deliver care for homebound individuals with MS and severe disability (EDSS score ≥7.5). This home-based program was designed to immediately address care delivery needs for those with MS in the program area.

Participant characteristics were similar to those identified in large studies of homebound elderly and included predominantly female, poorer health, and low income17; importantly, most participants were younger than 55 years and had significantly greater functional limitations. Moreover, half of the patients lived alone and were dual Medicare/Medicaid waiver eligible, suggesting near or at the poverty level. Most individuals struggled with transportation and many had difficulties with the availability of low-income Americans with Disabilities Act housing, consistent with national reports.18

The present evaluation found that during the combined pre- and post-MAHA implementation period, 50% of hospital admissions were due to potentially preventable complications, including infections, pressure/decubitus ulcers, and falls. These secondary complications were consistent with those reported in spinal cord injury–related disorders19 and MS.20 The number of hospitalizations for infections and falls with injury decreased in the post-MAHA period, thus meeting the program objective of reducing preventable common complications. However, it is important to note that one patient had a pressure/decubitus ulcer on program entry and three subsequent hospital admissions, with an LOS of 48 days along with skilled nursing facility days.

In the total cohort (n = 21), almost all targeted health care utilization metrics improved during the post-MAHA period, with the exception of ED visits only and hospital LOS. Although the improvements were not statistically significant given the sample size, results suggested that the number of skilled nursing facility admissions and LOS substantially improved during the post-MAHA period. As described previously herein, one patient with pressure ulcer was identified as an outlier because this patient's values for hospital days and skilled nursing facility days greatly influenced the mean values for those variables.

From the inception of the program, we welcomed those with present complications to avoid “cherry-picking,” or what would be exclusion criteria in traditional research designs. Severe pressure/decubitus ulcers with complications are expected in patients with advanced disability; obviously, prevention is paramount, but problems such as these should be anticipated, appropriately reported, analyzed, and addressed when developing programs for high-risk populations. Patients with spinal cord injury are the highest-risk population for pressure ulcers, with incidence rates from 25% to 66%.21

The number of ED visits only (without hospitalization) increased in the post-MAHA implementation period. A possible explanation for this is that ED providers may have been less likely to admit a patient to the hospital when a home care team was in place, as evidenced by the lower hospital admission rate. In addition, the “first calls” for patients were generally a home health care agency, and the call frequently was taken by nurses who were unfamiliar with the patient or possibly lacking expertise in MS. Further data are needed, but these results suggest that an expanded-hours urgent care clinic or urgent house calls should be included in the model.

The present cohort of generally younger individuals with advanced disability and MS (EDDS score ≥7.5) clearly meets the definition of “nursing home level of care.” All 21 patients wanted to remain in their homes versus live in a skilled nursing facility. Unlike relatively “fixed” spinal cord disability, a significant proportion of these patients had active inflammatory MS as evidenced by relapse and/or additional gadolinium-enhancing or new T2 lesions on magnetic resonance imaging, adding dynamic complexity to care requiring specialty management.

Home-based care models have been described and studied as alternatives to traditional outpatient clinic visits in high-risk, high-need patients. One of the first house call programs was established in 1967 for homebound children and is cited as the first PCMH. Current models of the PCMH are now applied to include broader ambulatory-based patient populations. Value-based Medicare reimbursement is linked to elements of the PCMH, including patient centeredness, emergency medical response, accessible medical records, and coordination of care. Recent reviews of PCMHs vary greatly, however significant opportunities in coordination of care serving high-risk, high-need patient populations have been identified.22 Reviews have also noted an added advantage of formally studying groups of high-need patients, documenting an improved power to detect effects, thus decreasing the number of patients needed and the likelihood of missing important beneficial effects of the application.23 Notably, cohorts of individuals with MS and significant disability likely present opportunities for MS and primary care providers to apply medical home concepts.

The literature reports only one randomized study of a medical home care model specific for MS. Pozzilli et al24 demonstrated a significant difference favoring home-based care, with improved quality-of-life measures and reduced costs by decreasing hospitalizations. A further nonrandomized study, also implemented in Europe, included provider house calls to patients with greater levels of disability; results demonstrated improved satisfaction and decreased health care utilization.25 Frequently cited large-scale successful in-home care programs generally serving frail elderly individuals include Medicare demonstration projects and have shown a variety of benefits. The Independence at Home demonstration projects used primary care house call providers and showed significant reductions in cost.26 Additional programs with intermittent use of house calls serving the elderly who require assistance with two or more ADLs include the Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) and Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE), which have also demonstrated benefit in caring for patients with high need levels.27 28 Because of the success of PACE, more diverse populations are being considered, including younger cohorts with disability.29 The Veterans Administration Home Based Primary Care has also demonstrated benefit in home care provided to veterans with complex chronic diseases not effectively managed by traditional clinic visits.30

Caring for patients with MS with advanced disability is exceedingly complex. Regarding the PCMH model, co-management, with close communication, collaboration, an MS specialist, and primary care providers, as in the present model, is likely a necessary approach. In our experience, palliative care models can be applied in the context of this complex, disabling disease. However, unique to this cohort is a younger age with significant disability, thus requiring a mindset that these individuals can still live relatively long and quality lives with quality care. In addition, as discussed in the Lessons Learned section, patients preferred a limited number of providers, with high expertise and productive visits.

Once medical conditions were stabilized, and safety and social issues were addressed, televisits were well received by our patients; however, only 50% of patients were able to use them. In addition to technological and financial limitations, a further barrier from a fee-for-service perspective is that televisits are not reimbursable but nonetheless seem valuable. Benefits of telemedicine are documented in other chronic neurologic illnesses, finding added advantages of saving patients significant time and expense,31 and preferred by patients compared with face-to-face visits with increased consistency in keeping appointments.32

Unique to the home-based MAHA program was the provider role of the MS comprehensivist, an advanced practice provider/NP with prescriptive privileges. This licensure was essential for expediting care elements, including prescriptions, medical equipment, and referrals. Approximately one-fourth of patients continued taking high-risk immunosuppressants to treat active inflammatory MS, and the NP, in partnership with the MS neurologist, followed up patients closely. The NP was readily accessible to home health agencies to provide care direction and facilitate timely treatments.

Nurse practitioners have been central providers in successful larger home-based care trials. In light of data showing an increased prevalence of MS in the United States, the shortage of general and subspecialty MS neurologists, as well as cost-benefit considerations, an advanced practice provider is both practical and beneficial for this initiative. Timely interventions likely contribute to preventing complications. Additional benefits of using NPs for this role are their familiarity with general systems theory and whole-care perspectives.

Limitations

The generalizability of this program is limited but possible in practices with greater volumes of disabled patients in a geographically condensed area. Likewise, a similar team composition may not be available in some locations. House calls by physicians/advanced practice providers are billable under Medicare provided specific requirements are documented, including homebound status. The MAHA program is presently financially sustainable or revenue/cost neutral in a fee-for-service structure. Generally, all the program participants were insured by Medicare or dual Medicare/Medicaid. Likely in the future, most patients with MS and advanced disability will fall under managed Medicare or Medicaid groups. Mature accountable care organizations with a focus on value-based structures may be better positioned to deliver this type of care. Sophisticated accountable care organizations may also have a supportive infrastructure, ie, designated home health care agencies, durable medical vendors, access to pharmacies, and integrated health information systems. Moreover, the application of all-inclusive care models with direct payment to providers and community partners, with appropriate revenue distribution, may be a better option for this type of service delivery for underserved, generally low-income, vulnerable, high-need populations. Because most studies have concentrated on cost reduction in decreased hospitalizations, more information on program costs is needed.

The initiative's intent was reliable program evaluation, including assessment of quality processes and outcomes. Obvious limitations included the absence of a control group and randomization, selection bias, and a low number of participants. However, an advantage to this type of quality-based iterative initiative is that it can provide immediate humanitarian benefit to high-need patients and in-depth knowledge acquisition and understanding, contributing to health care delivery services and program management.

Conclusion

Based on published studies, this seems to be the first report describing a house call program specifically designed for persons with disabling MS in the United States. In addition, we introduced the MS comprehensivist as a provider hybrid role, bridging subspecialty and primary care.

Results suggest that a comprehensive, hands-on, tightly integrated, community house call practice is a viable solution to improve care for patients with MS and severe disability and at high risk for complications. House call models specifically for those with significant disability and limited access to care likely will improve overall quality of care and contribute to practice, education, and health care delivery for all MS care. Changes in policy allowing advanced practice providers greater practice authority could be one solution for improved care for disabled individuals with highly complex chronic care needs. Importantly, at the current time, house calls provide a humanitarian role for serving patients with significant disability with no or poor access to care.

PRACTICE POINTS

Individuals with progressive MS and significant disability have complex, dynamic, and chronic health care needs. New care delivery models are needed to provide quality care, increase satisfaction, and improve outcomes, as well as prevent common secondary complications associated with this disability.

Comprehensive house calls by experienced providers with productive interactions at each visit improve the quality of needs assessments, allow additional time for complex coordination, and promote mutually developed holistic plans of care. In light of data showing an increased prevalence of MS in the United States, the shortage of general and subspecialty MS neurologists, as well as cost-benefit considerations, an advanced practice provider is both practical and beneficial for this initiative.

Programs for high-risk, high-need patients generally do not fit well in traditional fee-for-service, volume-based practices; mature, value-based organizations likely better serve the program goals. Caution is required, and thoughtful patient-focused conversations about the complex processes and appropriate expected outcomes should proceed with organizations interested in serving this high-risk, vulnerable group of individuals.

Acknowledgments

We primarily acknowledge those whom we served—individuals with MS and severe disability—who were unique, talented, tenacious, and often fiercely independent. The challenges for these individuals and their families were initially underestimated by our team; the lessons learned from them will undoubtedly help improve care for others with MS. We also thank the MS Foundation for their generous funding and salary support. We thank Melody A. Montgomery for her professional editing. We also note that practice guidelines identified to direct care included guidance from Paralyzed Veterans of America, the Kessler Foundation, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

References

Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Perloffp J, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12:24–38.

Wallin MT. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the United States: a population-based healthcare database approach. ECTRIMS Online Library. October 26, 2017. Abstract P344.

Foley PL, Vesterinen HM, Laird BJ, et al. Prevalence and natural history of pain in adults with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2013;154:632–642.

Naci H, Fleurence R, Birt J, Duhig A. The impact of increasing neurological disability of multiple sclerosis on health utilities: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Econ. 2010;13:78–89.

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Strategic Response White Paper 2011–2015. New York, NY: National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2016.

Arnett PA. Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1041.

American College of Physicians. The Patient-Centered Medical Home Neighbor: The Interface of the Patient-Centered Home with Specialty/Subspecialty Practices. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2010. Policy paper.

Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Hoaglin DC. Access to health care for people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:547–558.

Jones E, Pike J, Marshall T, Ye X. Quantifying the relationship between increased disability and health care resource utilization, quality of life, work productivity, health care costs in patients with multiple sclerosis in the US. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:294-016-1532-1.

Sauro KM, Quan H, Sikdar KC, Faris P, Jette N. Hospital safety among neurologic patients: a population-based cohort study of adverse events. Neurology. 2017;89:284–290.

Chiu C, Bishop M, Pionke JJ, Strauser D, Santens RL. Barriers in the accessibility and continuity of health-care services in people with multiple sclerosis: a literature review. Int J MS Care. 2017;19:313–321.

Young L, Healey K, Charlton M, Schmid K, Zabad R, Wester R. A home-based comprehensive care model in patients with multiple sclerosis: a study pre-protocol. F1000Res. 2015;4:872.

Wagner EH. Chronic disease care. BMJ. 2004;328:177–178.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452.

Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann. 1979;2:197–207.

Outlier: definition from The Free Dictionary by Farlex. https://Medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/outlier. Accessed January 3, 2018.

Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1180–1186.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, Health and Medicine Division, et al. Developing Affordable and Accessible Community-Based Housing for Vulnerable Adults: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017.

Sezer N, Akkus S, Ugurlu FG. Chronic complications of spinal cord injury. World J Orthop. 2015;6:24–33.

Wijnands JM, Kingwell E, Zhu F, et al. Infection-related health care utilization among people with and without multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23:1506–1516.

Russo CA, Steiner C, Spector W. Hospitalizations related to pressure ulcers among adults 18 years and older, 2006: statistical brief #64. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006.

Institute of Medicine, Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine; Yong PL, Saunders RS, Olsen LA(eds). The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes. Workshop Series Summary. 3, Inefficiently Delivered Services. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301:603–618.

Pozzilli C, Brunetti M, Amicosante AM, et al. Home based management in multiple sclerosis: results of a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:250–255.

Makepeace RW, Barnes MP, Semlyen JK, Stevenson J. The establishment of a community multiple sclerosis team. Int J Rehabil Res. 2001;24:137–141.

Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:2623–2633.

Eng C, Pedulla J, Eleazer GP, McCann R, Fox N. Program of all-inclusive care for the elderly (PACE): an innovative model of integrated geriatric care and financing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:223–232.

Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, Stump TE, Arling GW. Cost analysis of the geriatric resources for assessment and care of elders care management intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1420–1426.

PACE pilots: a new era for individuals with disabilities. National PACE Association website. https://www.npaonline.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/Spread%20and%20Scale%20Growth%20Strategies%20for%20PACE.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2019.

Beales JL, Edes T. Veteran's affairs home based primary care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:149–154, viii–ix.

Beck CA, Beran DB, Biglan KM, et al. National randomized controlled trial of virtual house calls for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2017;89:1152–1161.

Schreiber SS. Teleneurology for veterans in a major metropolitan area. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24:698–701.