Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Factors Associated with Postrelapse Rehabilitation Use in Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

Background:

Most people with multiple sclerosis (MS) have periodic and unpredictable relapses as part of their disease course. Relapses often affect functional abilities, resulting in diminished productivity and lower quality of life. Considering the effects, rehabilitation can play an important role in facilitating recovery; yet, the current literature suggests a lack of postrelapse rehabilitation services use. This study aims to document postrelapse rehabilitation services use and estimate the extent to which predisposing characteristics, perceived need, and enabling resources were associated with postrelapse rehabilitation services use in adults with MS.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study used convenience sampling, and data from 73 adults with MS who recently had a relapse in the United States and Canada were analyzed.

Results:

A total of 25 participants (34.2%) reported using postrelapse rehabilitation services. The regression model identified three variables associated with postrelapse rehabilitation services use: age (odds ratio [OR], 1.075), self-reported quality of life (considerably affected by the most recent relapse [OR, 5.717]), and presence of helpful health care providers (for obtaining postrelapse rehabilitation services [OR, 5.382]).

Conclusions:

Most participants experienced a range of symptoms or limitations because of their most recent relapse, affecting their daily activity and quality of life. However, only one-third of the participants reported using postrelapse rehabilitation services, which focused on the improvement of their physical health. Regression modeling revealed that three population characteristics of the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization were associated with postrelapse rehabilitation services use.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic progressive neurologic disease affecting more than two million individuals worldwide. Most people with MS have periodic and unpredictable relapses as part of their disease course.1 During the past 25 years, due to therapeutic advances, people with MS are reportedly having fewer relapses.2 Relapses, however, continue to have negative effects on people with MS who experience them.3 4 Consequences of relapses include reduced functional abilities and increased residual disabilities, resulting in diminished productivity (eg, ability to work and support the cost of living) and lower quality of life (QOL).5–7

Relapses are commonly treated with corticosteroids at the acute stage. Corticosteroids may lessen the acute inflammation, but they do not address the challenges of managing symptoms and disabilities magnified by relapses. Considering the consequences of relapses, rehabilitation can play an important role in facilitating recovery7 8; yet, the current literature suggests a lack of postrelapse rehabilitation services use in this population.3 7

The Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization9 is a widely used conceptual model that presents factors contributing to individuals' use of health services in a variety of disease populations. It suggests that health services use is determined by three characteristics: 1) predisposing characteristics, 2) perceived need, and 3) enabling resources.

The Andersen model has been applied to studies aimed at understanding factors associated with the use of various types of rehabilitation services,10–12 including MS. Beckerman et al13 applied the model to identify factors associated with the use of comprehensive health services among their Dutch patients with MS.

To our knowledge, there are no studies that applied the Andersen model to the context of postrelapse rehabilitation services use in people with MS. Identifying factors associated with the use of postrelapse rehabilitation services may prove useful to researchers and clinicians who work with people with MS to facilitate their relapse management and recovery process. Therefore, this study aimed to 1) document the use of rehabilitation services after relapse and 2) estimate the extent to which predisposing characteristics, perceived need, and enabling resources were associated with the use of rehabilitation services after relapse in adults with MS.

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional design and convenience sampling and engaged adults with MS in a telephone survey. The research ethics board (Queen's University) approved this study.

Recruitment, Sampling, and Procedure

We advertised this study in the research portals of the National MS Society and the MS Society of Canada and by collaborating with the midwestern and Ontario chapters of these MS societies, respectively. In addition, study invitation letters were mailed to potential participants who were residing in 1) the midwestern states in the United States through the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis and 2) the province of Ontario in Canada through a collaborating MS clinic.

In the advertisement and letter, interested individuals were asked to call the research office. Trained researchers (M.A., A.E., and L.D.) answered these calls, described the study, and responded to questions that these individuals had. When individuals were interested in participating, they underwent a brief screening procedure to confirm their eligibility.

To be eligible, an individual had to be 18 years or older, self-report a diagnosis of MS, and have a self-reported physician-confirmed relapse within 6 months (of their survey). The participants self-reported a physician-confirmed relapse by answering a simple question: Did your physician or neurologist tell you that you had a relapse in the past 6 months (yes or no)?

Measures and Data Analysis

Survey

The survey included questions about basic demographics (eg, age and sex), MS (eg, duration and Patient-Determined Disease Steps [PDDS] score14), MS relapse (eg, duration and self-reported impact), and postrelapse rehabilitation services use. The PDDS score is a patient-reported outcome of disability in MS (primarily based on ambulation). Its score ranges from 0 (normal) to 8 (bedridden).

Participants who did not use any postrelapse rehabilitation services were asked to answer a series of questions to identify their reasons. The survey development was informed by the findings of a previous study3 (which identified themes related to postrelapse management) and based on similar published work.15–19

Outcome

Postrelapse rehabilitation services use (yes or no) was the outcome of the regression model: “Did you use any rehabilitation services to manage the most recent relapse?” Based on the response, we classified participants as services users or nonusers for further analyses. A list of rehabilitation services for the survey included physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, psychologists, neuropsychologists, vocational therapists, physiatrists, kinesiologists, recreation therapists, nutritionists, assistive device specialists, and others (eg, chiropractors, acupuncturists, and massage therapists).

Indicators

Predisposing characteristics, perceived need, and enabling resources were the variables of interest in this study. Based on the Andersen model9 and the sample size, we selected six variables from the survey for the regression model.

First we selected age and sex (male or female) as predisposing characteristic variables. Second, we added self-reported level of disability (mild, moderate, or severe) and QOL (not affected, somewhat affected, or considerably affected) to the model as perceived need variables. We selected the two variables because 1) a previous study3 suggested that individuals' self-appraised capacity to perform desired daily activities influence how they determine their need for postrelapse care and 2) the present study collected no objective measures of symptoms or disabilities. Third, we added presence of insurance coverage for rehabilitation services (yes or no) and helpful health care providers (yes or no) as enabling resource variables. We selected the two variables because lack of insurance coverage is a known barrier to accessing health services.20

Regression Model

We conducted hierarchical multivariate logistic regression analysis. The model included three steps, each with two variables: step 1, predisposing characteristics (age and sex); step 2, perceived need (self-reported disability and QOL); and step 3, enabling resources (insurance coverage and presence of helpful health care providers). All the analyses were performed using available data and IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Participants

Of 119 individuals who contacted the research office, 27 (22.7%) were ineligible, mostly due to a lack of relapse in the past 6 months, and the remaining 92 (77.3%) completed the informed consent. Of these participants, three declined to proceed with the survey and two were unreachable, leaving a sample of 87 participants (73.1%) who completed the survey. This study analyzed the data obtained from a sample of 73 participants who responded to all seven questions necessary for the regression analysis.

The mean ± SD age of participants was 48.0 ± 10.7 years. Most participants were women (n = 64 [87.7%]) and were diagnosed with MS approximately a mean ± SD of 13.1 ± 9.1 years ago. The mean ± SD PDDS score was 3.3 ± 1.8, which suggests that, on average, the participants reported mild-to-moderate ambulatory disability.14 Approximately one-half of the participants (n = 36 [49.3%]) stated that their MS was stable or improving.

Participants completed the survey a mean ± SD of 94.6 ± 58.4 days after the occurrence of their relapse. At the time of the survey, most participants stated that their relapse had a noticeable effect on their daily life (n = 67 [91.8%]). They reported having problems with performing usual activities (n = 60 [82.2%]) and walking (n = 54 [74.0%]), being anxious or depressed (n = 45 [61.6%]), and experiencing pain or discomfort (n = 54 [74.0%]).

Postrelapse Rehabilitation Services: Users and Nonusers

Of 39 participants (53.4%) who sought immediate medical attention for their relapse, 25 (64.1%) received a consultation with their neurologist. Twenty-five participants (34.2%) reported using at least one rehabilitation service after relapse. The top three services used (ie, professionals seen) were physiotherapists (n = 19 [76.0%]), occupational therapists (n = 9 [36.0%]), and kinesiologists (n = 8 [32.0%]).

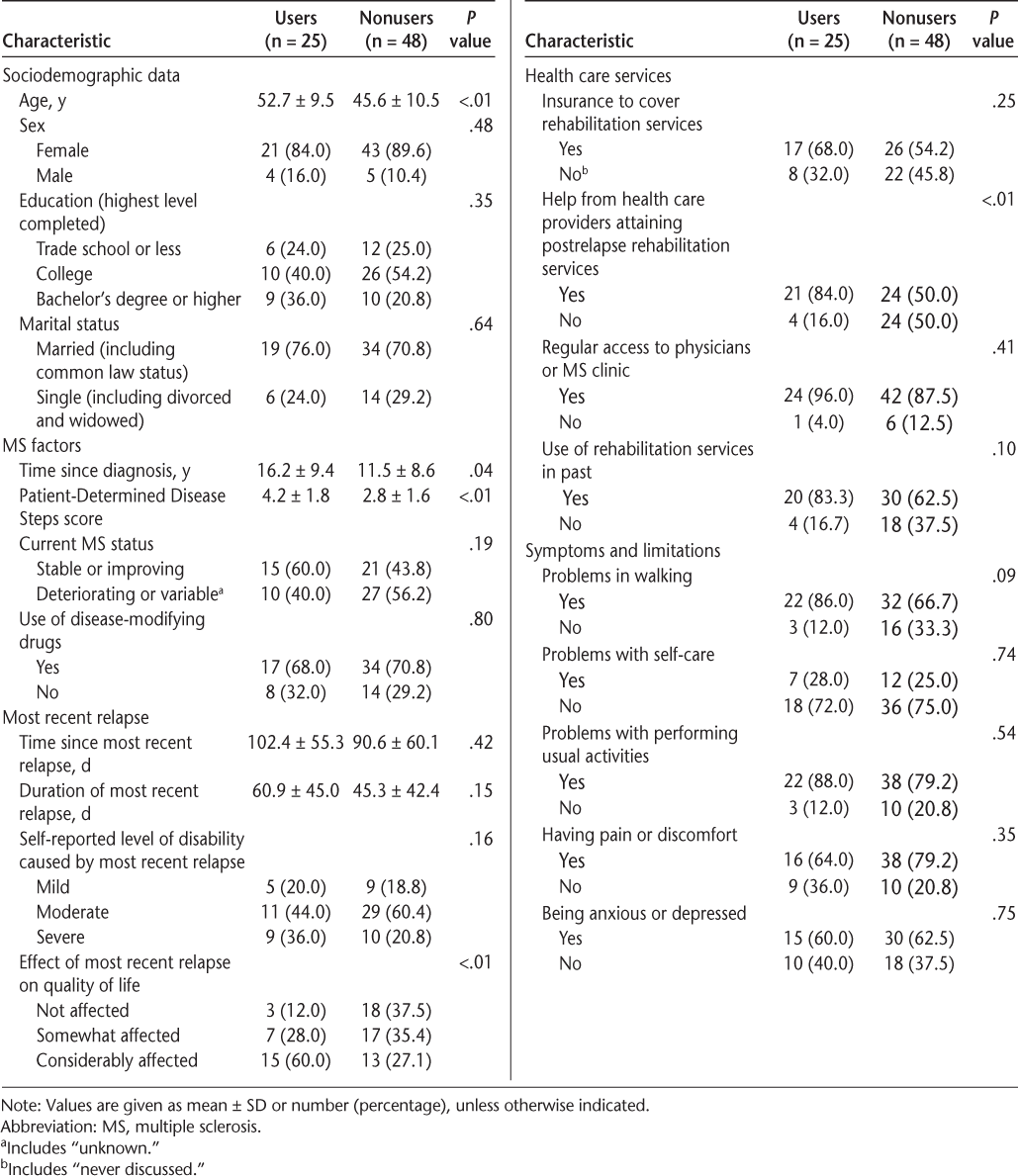

Participants who used no services (n = 48 [65.8%]) reported the following top three reasons for their decision: lack of recommendations from health care professionals (n = 29 [60.4%]), lack of information on how to or where to obtain the services (n = 23 [47.9%]), and lack of perceived necessity (n = 22 [45.8%]). In addition, 16 participants (33.3% of nonusers) stated that they did not know what rehabilitation services were. Table 1 presents characteristics of the 73 participants, arranged by their postrelapse rehabilitation services use status.

Characteristics of the 73 participants who recently had an MS relapse, grouped by postrelapse rehabilitation services use status

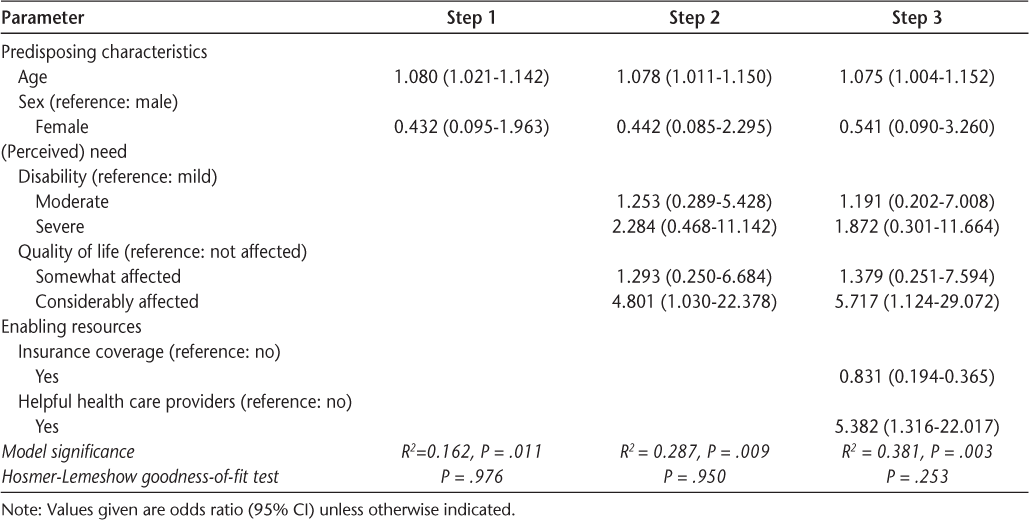

Regression Model of Postrelapse Rehabilitation Services Use

The regression model identified three variables (one from each population characteristic of the Andersen model9) associated with the use of postrelapse rehabilitation services: age (odds ratio [OR], 1.075; 95% CI, 1.004–1.152), self-reported QOL being considerably affected by the most recent relapse (OR, 5.717; 95% CI, 1.124–29.072), and presence of helpful health care providers (OR, 5.382; 95% CI, 1.316–22.017). In contrast, sex, self-reported level of disability, and presence of insurance coverage were not associated with use of the services.

The final model was significant (P = .003) and fit the data as shown by the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (P = .253). Table 2 summarizes the odds of being postrelapse rehabilitation services users from the regression analysis.

Regression model of postrelapse rehabilitation services use

Discussion

Therapeutic advances in treating MS have resulted in reduced rates of relapses and have slowed the progression of the disease.2 Many individuals with MS, however, still continue to experience periodic relapses,4 often leading to residual disabilities and decreased QOL.4–6 21 The existing literature is limited but suggests a lack of access to rehabilitation services for managing the consequences of relapses.3 22 This study documented the use of postrelapse rehabilitation services and estimated the extent to which predisposing characteristics, perceived need, and enabling resources were associated with postrelapse rehabilitation services use in MS.

Postrelapse Rehabilitation Services

Given the range of symptoms and limitations as well as the high prevalence of disabilities reported by the participants, we (as rehabilitation researchers) were expecting to identify the use of various types of rehabilitation services; yet, only one-third of the participants reported using rehabilitation services, most likely focusing on physical disabilities. A recent British study that surveyed 732 individuals with MS who had a relapse reported similar postrelapse rehabilitation services use rates from 3% for rehabilitation doctors to 38% for physiotherapists.22

The present survey identified three common reasons why participants (n = 48 [65.8%]) did not use any rehabilitation services after relapse: lack of recommendations from health care professionals, perceived necessity, and information on how to or where to obtain the services. We also learned that 33.3% of the participants (16 of 48 who used no rehabilitation services) did not know what rehabilitation services were. A recent Norwegian qualitative study reported 1) availability and suitability of information, 2) assumptions and expectations about rehabilitation, and 3) life situation as important factors influencing the use of MS rehabilitation services.23 Lack of knowledge and/or information about rehabilitation services (eg, what they are) can be a barrier for individuals with MS to attain appropriate health care services after relapse. A future study aimed at better understanding individuals with MS's knowledge or information on relapse management is warranted.

Postrelapse Rehabilitation Services Users

This was a pilot study with a small sample size. However, the regression analysis identified that all three population characteristics of the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization were associated with the use of rehabilitation services among adults with MS. Older individuals who reported their QOL being considerably affected by the most recent relapse with the presence of helpful health care providers were more likely to use rehabilitation services.

We must, however, interpret the results of this regression analysis carefully due to the wide 95% CIs. Most likely, the two wide 95% CIs are owing to response options with small frequencies, as well as the small sample size of the study (Table 1).24 A future study with a larger sample size is, thus, crucial to obtain more precise estimates and to confirm the current findings of this study.

In general, older populations are more likely to have more health conditions and a higher level of disability requiring medical attention. We were not surprised to learn that age (being older) was associated with the use of rehabilitation services. This finding may suggest a lack of postrelapse rehabilitation services use in younger individuals with MS, for reasons that have yet to be discussed in the literature. Multiple sclerosis is commonly diagnosed in young adults (aged 20–40 years) in North America, who often experience periodic relapses throughout their disease course. This finding may suggest the importance of a future study in young adults with MS to learn about their relapse management.

Perceived health and functional status are considered measures of “need” in the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization.9 Individuals who present the need for health care are more likely to use the services. In the present study, we considered self-reported QOL and level of disability as measures of perceived need for rehabilitation services. The regression analysis found that participants who self-reported their QOL being considerably affected by the most recent relapse were 5.7 times more likely to use rehabilitation services (compared with those who reported their QOL being unaffected by the relapse), whereas the level of self-reported disability (affected by the relapse) was not associated with the use of rehabilitation services. A previous study3 suggested that while determining an individual's need for postrelapse care, one's self-appraised capacity to perform desired activities in their daily life weighed in more than levels of limitations that they experienced. The finding of the present study supports the importance of understanding people with MS beyond their functional limitations (eg, lifestyle, occupation, and role).

Enabling resources (eg, insurance coverage, access to health care services, and extent and/or quality of social relationships) are the logical aspects of successfully obtaining health care services. Individuals who are adequately resourced are more likely to access health care services (compared with those who are inadequately resourced).

We were surprised to learn that having insurance was not associated with the use of rehabilitation services in the study participants. Lack of knowledge about rehabilitation services or understanding of insurance (coverage) may explain the finding. We were not surprised to find that participants who self-reported the presence of helpful health care providers were 5.4 times more likely to use rehabilitation services (compared with those who reported the absence of helpful health care providers). Health care providers' levels of knowledge of rehabilitation services may influence the likelihood of them recommending the services to their patients. Unfortunately, the present study collected no information on health care providers (eg, backgrounds, types, and settings) who worked with the participants during their relapse management or recovery period. This finding underlines a need for future studies to understand the relapse management from not only the patient's but also the health care provider's point of view.

Study Limitations

During the survey, the participants self-reported their health, MS and relapse status, and the use of rehabilitation services. We were unable to objectively measure functional limitations due to the relapse, confirm the exact date of the relapse occurrence (eg, neurologic examinations, performance-based tests), or validate the use of rehabilitation services (via medical records). These are the main limitations of the study. Future studies should collect data from clinics where they treat patients for their relapse to resolve the limitations.

We had no measures to screen and exclude the participants with cognitive impairment from the study. Furthermore, the participants completed their survey approximately 3 months after the occurrence of their self-reported relapse. These additional limitations might have affected participants' understanding of and responses to the survey questions.

Conclusion

Most participants in this study reported a range of symptoms and/or limitations due to their relapse, affecting their daily activity and QOL. However, only one-third of them used rehabilitation services after relapse. Although the sample size was small, the regression analysis revealed that all three population characteristics of the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization were associated with the use of rehabilitation services. Future longitudinal studies with a larger sample size are warranted to gain deeper understanding of the relapse management process at both a person and system level in the continuum of care, to support the findings of this study.

PRACTICE POINTS

This study documented postrelapse rehabilitation services that adults with MS used and factors associated with postrelapse rehabilitation services use.

Postrelapse rehabilitation services used by adults with MS focused on the improvement of physical health (such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and exercise therapy).

Postrelapse rehabilitation services use was associated with predisposing characteristics (age), perceived need (effect of relapse on quality of life), and enabling resources (presence of helpful health care providers) in this pilot study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the individuals who participated in the survey and all the organizations (National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, and Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers [CMSC]) and their personnel who assisted us in the recruitment process.

References

Zajicek J. The epidemiology of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254:1742.

Inusah S, Sormani MP, Cofield SS, et al. Assessing changes in relapse rates in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010;16:1414–1421.

Asano M, Hawken K, Turpin M, Eitzen A, Finlayson M. The lived experience of multiple sclerosis relapse: how adults with multiple sclerosis processed their relapse experience and evaluated their need for postrelapse care. Mult Scler Int. 2015;2015:351416.

Oleen-Burkey M, Castelli-Haley J, Lage MJ, Johnson KP. Burden of a multiple sclerosis relapse: the patient's perspective. Patient. 2012;5:57–69.

Lublin FD, Baier M, Cutter G. Effect of relapses on development of residual deficit in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2003;61:1528–1532.

Healy BC, Degano IR, Schreck A, et al. The impact of a recent relapse on patient-reported outcomes in subjects with multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1677–1684.

Asano M, Raszewski R, Finlayson M. Rehabilitation interventions for the management of multiple sclerosis relapse: a short scoping review. Int J MS Care. 2014;16:99–104.

Khan F, Amatya B. Rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:353–367.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10.

Johnson JE, Weinert C, Richardson JK. Rural residents' use of cardiac rehabilitation programs. Public Health Nurs. 1998;15:288–296.

Finlayson M, DalMonte J. Predicting the use of occupational therapy services among people with multiple sclerosis in Atlantic Canada. Can J Occup Ther. 2002;69:239–248.

Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Powe NR, Steinwachs DM, Eaton WW, Ford DE. Mental health service utilization by African Americans and whites: the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-Up. Med Care. 1999;37:1034–1045.

Beckerman H, van Zee IE, de Groot V, van den Bos GA, Lankhorst GJ, Dekker J. Utilization of health care by patients with multiple sclerosis is based on professional and patient-defined health needs. Mult Scler. 2008;14:1269–1279.

Hohol MJ, Orav EJ, Weiner HL. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a simple approach to evaluate disease progression. Neurology. 1995;45:251–255.

Finlayson M, Plow M, Cho C. Use of physical therapy services among middle-aged and older adults with multiple sclerosis. Phys Ther. 2010;90:1607–1618.

Plow M, Cho C, Finlayson M. Utilization of health promotion and wellness services among middle-aged and older adults with multiple sclerosis in the mid-west US. Health Promot Int. 2010;25:318–330.

Chipperfield JG, Havens B, Doig W. Method and description of the Aging in Manitoba Project: a 20-year longitudinal study. Can J Aging. 1997;16:606–625.

Kersten P, McLellan DL, Gross-Paju K, et al. A questionnaire assessment of unmet needs for rehabilitation services and resources for people with multiple sclerosis: results of a pilot survey in five European countries: Needs Task group of MARCH (Multiple Sclerosis and Rehabilitation, Care and Health Services Research in Europe). Clin Rehabil. 2000;14:42–49.

Kersten P, Low JT, Ashburn A, George SL, McLellan DL. The unmet needs of young people who have had a stroke: results of a national UK survey. Disabil Rehabil, 2002;24:860–866.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Access to health services. HealthyPeople.gov website. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Access-to-Health-Services. Accessed September 14, 2016.

Nickerson M, Cofield SS, Tyry T, Salter AR, Cutter GR, Marrie RA. Impact of multiple sclerosis relapse: the NARCOMS participant perspective. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4:234–240.

Hawton AJ, Green C. Multiple sclerosis: relapses, resource use, and costs. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17:875–884.

Helland CB, Holmøy T, Gulbrandsen P. Barriers and facilitators related to rehabilitation stays in multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:122–129.

Du Prel J-B, Hommel G, Röhrig B, Blettner M. Confidence interval or P-value? part 4 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. 2009;106:335–339.