Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Multiple Sclerosis Adult Day Programs and Health-Related Quality of Life of Persons with Multiple Sclerosis and Informal Caregivers

Abstract

Background:

Multiple sclerosis adult day programs (MSADPs) offer life-enhancing services for individuals and informal caregivers affected by multiple sclerosis (MS), including medical care, rehabilitation therapies, nutrition therapy, cognitive training, tailored education, exercise programs, and social interaction. The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of MSADPs on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and health care utilization of persons with MS and HRQOL and well-being of informal caregivers.

Methods:

Using a quasi-experimental design, outcomes between baseline and 1-year follow-up in persons with MS and informal caregivers who used MSADP services and a comparison group of similar persons with MS and caregivers who did not use MSADP services were compared. For persons with MS, outcomes included standardized measures of physical and mental HRQOL and health care utilization. For caregivers, outcomes included physical and mental HRQOL and well-being. Changes in outcomes between baseline and follow-up were examined using propensity score–weighted difference-in-differences regression analysis.

Results:

For persons with MS, MSADP use had a significant positive effect on 12-Item Short Form Health Survey physical component scores, although the difference was not clinically meaningful. Use of MSADPs did not have effects on any other outcomes for persons with MS or caregivers.

Conclusions:

Use of MSADPs did not show a clinically meaningful effect on HRQOL for persons with MS or informal caregivers. The MSADPs do not seem to offer sustained benefits to persons with MS or caregivers, but the possibility of initial short-term benefits cannot be ruled out.

The early age at onset and the unpredictability of multiple sclerosis (MS) affect health-related quality of life (HRQOL) for individuals with MS and their caregivers.1–4 In addition to influencing HRQOL, the course and severity of MS symptoms also affect the frequency and type of health care utilization. Compared with a non-MS population, people with MS have significantly higher rates of hospitalizations and emergency department and outpatient visits,5 and 5% to 10% of people with MS need extended nursing home care.5 Informal caregivers, such as spouses, relatives, or friends, also frequently report poor mental and physical health outcomes and personal sacrifices relating to their caregiving responsibilities.6–10

Multiple sclerosis adult day programs (MSADPs) offer life-enhancing services for individuals and informal caregivers affected by MS. Services offered may include medical care, rehabilitation therapies, nutrition therapy, cognitive training, tailored education, exercise programs, and social interaction that allow those with MS to stay actively engaged in their communities. The MSADPs also provide case management to organize health care and monitor health issues with the intention of decreasing more costly health care utilization, such as emergency department visits and hospital admissions. The MSADPs conform to a wellness service delivery model. Wellness is “an active process through which people become aware of, and make choices toward, a more successful existence.”11 Wellness involves physical, emotional, social, intellectual, and spiritual dimensions (Figure 1) and includes activities that encourage personal empowerment and growth.12 The overall goal of MSADPs is to enable members to think positively about their health and achieve a balanced lifestyle despite having a chronic illness. There are two types of MSADPs that differ in duration of participation. Short-term MSADPs usually have durations of 10 to 12 weeks, whereas long-term MSADPs have participants who attend for many years.

Multiple sclerosis wellness model

Studies of the benefits of a multidimensional wellness approach to MS treatment have yielded mixed results. McGuire et al13 measured the impact of a 10-week MS psychoeducational wellness program on quality of life for participants. The authors reported improvements in depression, anxiety, mental health, perceived stress, and pain in the treatment group compared with a control group. Hart and colleagues14 designed a pilot program incorporating 12 weekly 5-hour educational sessions across each of the wellness model’s domains. They found depression, functional status, and fatigue improvements for participants. However, the findings are difficult to interpret due to the lack of a control group.

Other studies of wellness programs have shown no or mixed effects. Smith et al15 examined the effects of MSADPs on HRQOL and health care utilization in persons with MS receiving services at five MSADPs and a similar group of individuals recruited from the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry. Although participation had a significant positive effect on social support, all of the other effects were either not significant or favored the comparison group. Di Fabio et al16 found that participation in outpatient rehabilitation services at an MS Achievement Center was significantly associated with decreased symptom frequency and fatigue but not with functional status at 1-year follow-up compared with a wait-list control group.

Although no known studies have examined the effects of MSADPs on caregiver burden and quality of life, Guagenti-Tax and colleagues17 evaluated a comprehensive model of MS-specific long-term care that included a twice-monthly medical day care component along with semiannual workshops for persons with MS and family caregivers; monthly home visits with a social worker, nurse, or volunteer; and case management and liaison services. Data were collected over a 2-year period from the treatment group (30 patient-caregiver units) and the control group (29 patient-caregiver units). Caregivers of the control group (persons with MS randomized to standard care) reported significant decreases in perceived health and increased interference of physical health problems and caregiving responsibilities with social activities. Caregivers in the treatment group did not exhibit such significant declines on the same measures.

Wellness services such as those offered by MSADPs are among the least likely type of health care service to be covered by insurance companies.18 More research on the efficacy of MSADPs is warranted. The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of MSADP use on the HRQOL and health care utilization of persons with MS and on the HRQOL of informal caregivers. The study tests whether MSADPs offset the physical and mental declines, increased health care utilization, and increased caregiver burden that are expected to occur over time. The study extends the work of Smith et al15 to include a larger number of MSADPs and to examine the potential effects on informal caregivers.

Methods

Procedures

We recruited persons with MS and informal caregivers from ten MSADPs. The MSADP staff informed members of the study and distributed invitation letters and an informational brochure about the study. The letters provided a toll-free telephone number for members and informal caregivers to call to enroll in the study. All of the recruitment materials indicated that informal caregivers included family members, friends, and neighbors but not paid caregivers such as home health aides or personal care assistants.

The comparison group was recruited from the NARCOMS Registry and iConquerMS, a patient network for people with MS. The NARCOMS sent a letter to 1000 persons with MS inviting them and their informal caregivers to participate in the study. The NARCOMs comparison group was limited to persons with MS in the same states as the MSADPs and with Patient-Determined Disease Steps scale scores greater than 5. iConquerMS e-mailed members nationwide inviting them to enroll in the study. All of the comparison group recruitment materials included a toll-free number to call to enroll in the study and stipulated that individuals were ineligible if they were using MSADP services.

Data were collected from baseline and follow-up surveys of persons with MS and informal caregivers in the MSADP and comparison groups. The follow-up survey took place 12 months after the baseline survey. The surveys were conducted using computer-assisted telephone interviewing. Persons with MS and their informal caregivers were provided a $25 Target gift card to complete each survey. Each survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete. Procedures were approved by the Westat institutional review board and institutional review boards associated with each site.

Outcome Measures

This study collected the following outcome measures for persons with MS. Health-Related Quality of Life: The 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) is a subset of 12 items from the SF-36.19 The items were used to create two scores: the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS).20 Fatigue: The five-item Modified Fatigue Impact Scale is the abbreviated version of the Fatigue Impact Scale, which examines the extent to which fatigue has affected the respondent’s life in the past 4 weeks in terms of physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning.21,22 Pain: The six-item Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Pain Effect Scale, modified from the MOS Functioning and WellBeing Profile, assesses pain and unpleasant sensations and how they affect moods, walking, sleeping, working, recreation, and the ability to enjoy life in the past 4 weeks.23 Depression: The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 10 is a ten-item variant of the original 20-item scale.24,25 Social Support: The Emotional/Information Support subscale of the MOS Social Support Survey assesses access to a support system, including the availability of someone they can talk to and share problems with, they can receive information and good advice from, and who understands and can help them understand their situation.26 Complications of MS: Persons with MS also reported on physical falls, broken bones, urinary tract infections, bed sores, number of days in the hospital (inpatient), and number of emergency department visits.

The following outcome measures were collected for caregivers. Health-Related Quality of Life: The same SF-12 was used to survey caregivers. Role Overload: The role overload scale includes three items that measure the caregiver’s perceived experience of feeling overloaded or worn out. Role Captivity: Role captivity includes three items that focus on the perceived feeling of being trapped in the caregiver role.27 Affect: The Midlife Development in the United States Affect subscale includes anxiety (three items), depression (five items), anger (three items), and positive affect (nine items).28

Statistical Analysis

Propensity scores were used to address differences between the MSADP and comparison groups.29 Propensity scores were derived separately for persons with MS and informal caregivers using a logit model wherein the dependent variable was whether the person with MS (or informal caregiver) was in the MSADP group or the comparison group. Variables included in the propensity score models were those that may be related to MSADP use or the outcomes.30 After computation of propensity scores, the comparison groups for persons with MS and informal caregivers were weighted by the odds of the propensity scores.31 This gives higher weights to comparison group members whose propensity scores are more similar to those in the MSADP group. Balance was checked using a measure of the absolute standardized difference, on which values greater than 0.25 are considered imbalanced.32

Effects of MSADPs on persons with MS and informal caregivers were estimated using difference-in-differences (DiD) regression analysis. The DiD regression is a statistical technique that can control for unobserved confounders in observational data.33 The DiD regression models were weighted by the odds of the propensity score and also included as control variables all of the variables used to calculate propensity scores to address any residual confounding after weighting and to increase precision.

Results

A total of 220 persons with MS in the MSADP group and 330 persons with MS in the comparison group completed the baseline survey. On average, persons with MS in the MSADP group had been attending their MSADPs for 4.3 years at baseline. A total of 104 caregivers in the MSADP group and 149 caregivers in the comparison group completed the baseline survey. Because the study examined changes over time in the outcome measures, only persons with MS and caregivers who responded to both the baseline and follow-up surveys were included in the final analytic sample. Data were available on 199 persons with MS in the MSADP group (90% of those interviewed at baseline) and 301 persons with MS in the comparison group (91% of those interviewed at baseline). Of persons with MS in the MSADP group who did not participate, 18 were unresponsive, one refused, and two were deceased or sick. Of persons with MS in the comparison group who did not participate, eight were unresponsive, 17 refused, and four were deceased or sick. At follow-up, 95% of persons with MS were still attending their MSADP.

Data were available on 82 caregivers in the MSADP group (79% of those interviewed at baseline) and 125 caregivers in the comparison group (84% of those interviewed at baseline). Of caregivers in the MSADP group who did not participate, 19 were unresponsive, two refused, and one was deceased. Of caregivers in the comparison group who did not participate, 14 were unresponsive, four refused, and six were no longer caring for the person with MS.

Propensity score analysis imposes a common support requirement, which assumes that the distribution of propensity scores (and observed covariates) overlap sufficiently between the MSADP and comparison groups. Program effects that are estimated outside of the region of overlap are likely to be biased. The analysis was restricted to the region of common support using minimum and maximum criteria.34 We excluded 21 comparison group cases with propensity scores lower than the lowest propensity score in the MSADP group and 20 MSADP group cases with propensity scores higher than the highest propensity score in the comparison group. After propensity score weighting, all of the covariates were balanced (Table S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org).

Imposing common support requirements led to the deletion of six caregivers in the MSADP group and two in the comparison group. Propensity score weighting was effective in eliminating all of the differences between the two groups except for low income, which remained imbalanced in the weighted sample (Table S2).

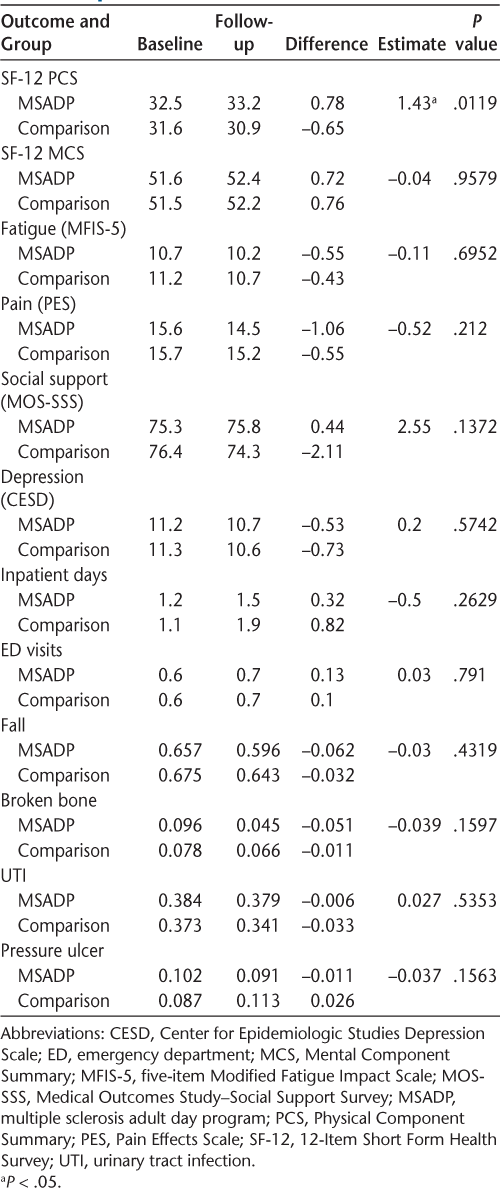

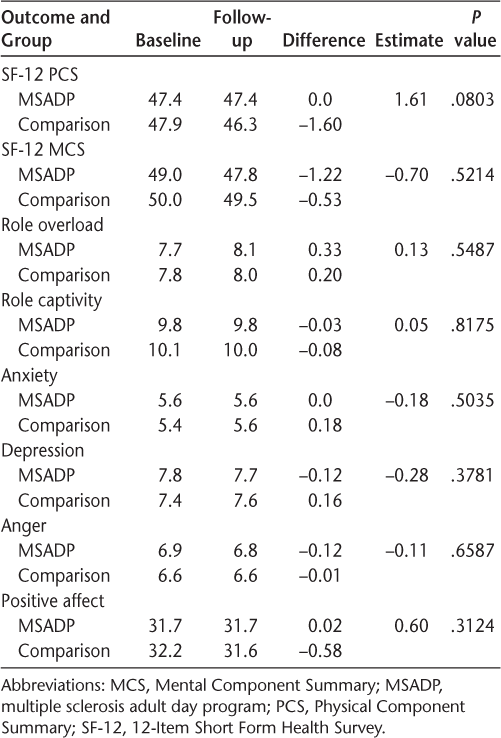

Use of MSADPs had a significant effect on SF-12 PCS scores (Table 1). The mean SF-12 PCS scores of the MSADP group increased, and those in the comparison group decreased from baseline to follow-up. However, this difference of 1.43 was below the threshold of 3 to 5 points that is generally considered clinically meaningful for SF-12 PCS scores.35–37 For persons with MS, there was little change in any of the other outcomes between baseline and follow-up in either the MSADP group or the comparison group. As such, there were no significant effects of the program on any of the other outcome measures. For caregivers, there was little change in the outcomes between baseline and follow-up in either the MSADP group or the comparison group (Table 2).

Regression-adjusted difference-in-differences estimates of MSADP use for persons with multiple sclerosis

Regression-adjusted difference-in-differences estimates of MSADP use for informal caregivers

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate whether MSADP participation delays declines in HRQOL of persons with MS and informal caregivers over 12 months. We found that relative to persons with MS in the comparison group, those in the MSADP group had similar trajectories of HRQOL over the 12-month follow-up period. Neither group had declines in HRQOL. The results were similar for informal caregivers; there was little change in HRQOL for either the MSADP group or the comparison group.

The findings from this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, most participants in the MSADP group were enrolled in their MSADPs before the start of the study. The study may have missed initial short-term effects of MSADP participation after a member enrolls. The MSADPs do not seem to offer sustained benefits, but the study cannot rule out the possibility of short-term benefits. Second, some persons with MS and caregivers in the comparison group were engaged in activities similar to those offered by MSADPs, which may have diluted the effects of MSADP use. Specifically, 44% of persons with MS in the comparison group participated in an exercise or social support program in the 12 months before baseline, and 12% of comparison group caregivers participated in individual counseling or caregiver support groups. Finally, the relatively short follow-up precluded examination of effects on long-term outcomes, such as the need for long-term care.

An ideal study would be a randomized trial in which interested persons with MS and informal caregivers were assigned to an MSADP group or a control group and followed up over a long period. Unfortunately, most MSADP members were attending for several years, and the number of new members is too small to make a randomized trial feasible. However, the findings from this study underscore the importance of continued research on wellness for persons with MS. Persons with MS are increasingly interested in wellness approaches rather than pharmacologic approaches to managing the symptoms of MS.38 Future research should focus on specific interventions for improving wellness, including diet, exercise, and emotional wellness. Well-designed randomized trials are needed. Effective interventions can be incorporated into wellness programs in a mix and intensity needed to have a positive effect. In this vein, the National MS Society recently established a working group to generate and promote wellness research.39 Future high-quality research on wellness can improve the health and well-being of people with MS and informal caregivers.

PRACTICE POINTS

The early age at onset and the unpredictability of the disease trajectory affect health-related quality of life for individuals with MS and their caregivers and create a unique set of circumstances for care management.

Specialized programs such as MS adult day programs (MSADPs) offer life-enhancing services for individuals and informal caregivers affected by MS that may include medical care, rehabilitation therapies, nutrition therapy, cognitive training, tailored education, exercise programs, and social interaction that allow those with MS to stay actively engaged in their communities.

The MSADPs do not seem to offer sustained benefits for persons with MS and informal caregivers compared with usual care, but the possibility of initial short-term benefits cannot be ruled out.

Financial Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Amtmann D, Bamer AM, Kim J, Chung H, Salem R. People with multiple sclerosis report significantly worse symptoms and health related quality of life than the US general population as measured by PROMIS and NeuroQoL outcome measures. Disabil Health J . 2018; 11: 99– 107.

Aronson KJ. Quality of life among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Neurology . 1997; 48: 74– 80.

Solari A, Ferrari G, Radice D. A longitudinal survey of self-assessed health trends in a community cohort of people with multiple sclerosis and their significant others. J Neurol Sci . 2006; 243: 13– 20.

Patti F, Amato MP, Battaglia MA, et al. Caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a multicentre Italian study. Mult Scler . 2007; 13: 412– 419.

Asche CV, Singer ME, Jhaveri M, Chung H, Miller A. All-cause health care utilization and costs associated with newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis in the United States. J Manag Care Pharm . 2010; 16: 703– 712.

Bayen E, Papeix C, Pradat-Diehl P, Lubetzki C, Joël ME. Patterns of objective and subjective burden of informal caregivers in multiple sclerosis. Behav Neurol . 2015; 2015: 1– 10.

Buchanan RJ, Huang C, Zheng Z. Factors affecting employment among informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care . 2013; 15: 203– 210.

Chipchase SY, Lincoln NB. Factors associated with carer strain in carers of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil . 2001; 23: 768– 776.

Figved N, Myhr KM, Larsen JP, Aarsland D. Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis: the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry . 2007; 78: 1097– 1102.

Sherman TE, Rapport LJ, Hanks RA, et al. Predictors of well-being among significant others of persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler . 2007; 13: 238– 249.

About wellness. National Wellness Institute website. http://www.nationalwellness.org/?page=AboutWellness.

Northrop DE, Frankel D. Serving Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis in Adult Day Programs: Guidelines and Recommendations . National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2010.

McGuire K, Stojanovic-Radic J, Strober L, Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Development and effectiveness of a psychoeducational wellness program for people with multiple sclerosis: description and outcomes. Int J MS Care . 2015; 17: 1– 8.

Hart DL, Memoli RI, Mason B, Werneke MW. Developing a wellness program for people with multiple sclerosis: description and initial results. Int J MS Care . 2011; 13: 154– 162.

Smith K, Trisolini M, Maier J, Kenyon A. Evaluation of the Effects of Multiple Sclerosis Adult Day Programs on Health Outcomes: Final Report. National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 2010.

Di Fabio RP, Soderberg J, Choi T, Hansen CR, Schapiro RT. Extended outpatient rehabilitation: its influence on symptom frequency, fatigue, and functional status for persons with progressive multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 1998; 79: 141– 146.

Guagenti-Tax EM, DiLorenzo TA, Tenteromano L, LaRocca NG, Smith CR. Impact of a comprehensive long-term care program on caregivers and persons with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care . 2000; 2: 23– 39.

Miller D. Health Needs, Utilization, and Cost Coverage in MS: A NARCOMS, NMSS, iConquerMS Survey. Poster presented at: 7th Joint European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS)–Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) Meeting, Paris, France, October 25–28, 2017.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SS. A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996; 34: 220– 233.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. 2nd ed. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995.

D’Souza E. Modified Fatigue Impact Scale–5-item Version (MFIS-5). Occup Med . 2016; 66: 256– 257.

Fisk J, Pontefract A, Ritvo P, Archibald C, Murray TJ. The impact of fatigue on patients with multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci . 1994; 21: 9– 14.

Ritvo P, Fischer J, Miller D, Andrews H, Paty D, LaRocca N. Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory: A User’s Manual. National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 1997.

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med . 1994; 10: 77– 84.

Zhang W, O’Brien N, Forrest J, et al. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 Item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One . 2012; 7: e40793.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991; 32: 705– 714.

Liu Y, Kim K, Zarit SH. Health trajectories of family caregivers: associations with care transitions and adult day service use. J Aging Health . 2015; 27: 686– 710.

Grossman MR, Gruenewald TL. Caregiving and perceived generativity: a positive and protective aspect of providing care? Clin Gerontol . 2017; 40: 435– 447.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika . 1983; 70: 41– 55.

Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Sturmer T. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol . 2006; 163: 1149– 1156.

Hirano K, Imbens GW, Ridder G. Efficient estimation of average treatment effects using the estimated propensity score. Econometrica . 2003; 71: 1161– 1189.

Stuart E. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and look forward. Stat Sci . 2010; 25: 1– 21.

Dimick JB, Ryan AM. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA . 2014; 312: 2401– 2402.

Caliendo M, Kopeinig S. Some Practical Guidance for the Implementation of Propensity Score Matching. Bonn, Germany: IZA; May 2005. Discussion Paper No. 1588.

Bjorner JB, Wallenstein GV, Martin MC, et al. Interpreting score differences in the SF-36 vitality scale: using clinical conditions and functional outcomes to define the minimally important difference. Curr Med Res Opin . 2007; 23: 731– 739.

Díaz-Arribas MJ, Fernández-Serrano M, Royuela A, et al. Minimal clinically important difference in quality of life for patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017; 42: 1908– 1916.

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA . 1989; 262: 907– 913.

Dunn M, Bhargava P, Kalb R. Your patients with multiple sclerosis have set wellness as a high priority—and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society is responding. US Neurol. 2015; 11: 80– 86.

Motl RW, Mowry EM, Ehde DM, et al. Wellness and multiple sclerosis: the National MS Society establishes a Wellness Research Working Group and research priorities. Mult Scler. 2018; 24: 262– 267.