Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Influence of Occupational Therapy on Resilience in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis

This quasi-experimental pilot study examined the impact of multidisciplinary care, with a particular focus on occupational therapy (OT), on resilience in individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS). Individuals with a diagnosis of MS who were receiving multidisciplinary care including outpatient OT at an MS center were invited to participate. A total of 36 individuals agreed to enroll and were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire and the Resilience Scale (RS). After an 8-week period of multidisciplinary treatment, the 35 individuals who completed treatment were again asked to complete the RS. As a group they demonstrated statistically significant improvement in resilience. A cohort of participants unexpectedly did not follow through with OT but did follow through with their other referrals. These individuals completed the RS before and after the 8-week time period and became an ad hoc control group. The group receiving OT showed significant improvement in resilience, while the control group did not. This study shows that a multidisciplinary approach to care, especially when it includes OT, is effective in treating individuals with MS. Occupational therapy focuses on treating symptoms that specifically limit daily functioning and participation, and may be uniquely positioned to affect resilience. Because resilience plays an important role in functional recovery and maintenance, this study suggests that OT may be a critical component of MS care in developing characteristics that enhance resilience.

The term resilience, a complex construct, is generally defined as an individual's capacity for positive adaptation in response to stress or adversity.1–5 Examples of adversity include socioeconomic disadvantage, chronic illness, and catastrophic life events.6 Multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic, potentially disabling illness, is an example of stress or adversity in which a person must respond to the unpredictability of the disease course, symptomatology, and possible disability. The term resilience is sometimes confused with similar words such as motivation or self-regulation. An individual can be motivated or have self-regulation without having to face adversity. However, resilience specifically refers to the ability to positively adapt to adversity, such as a disease like MS. This study addresses resilience in adaptation to MS.

The concept of resilience has been examined in numerous populations, including those distinguished by age and by challenge.3 7 Resilience is influenced by various factors, such as internal personality constructs and external individual environments that determine adjustment to “at risk” circumstances.8 Because resilience can be measured only if an individual is exposed to adversity,9 previous researchers have suggested that individual resilience may be inherent and not subject to modification. Only recently has it been suggested that resilience may be learned.1

Researchers have proposed that resilience can be enhanced through provision of opportunities for promoting mastery and problem solving,10 and that those who are resilient tend to use adaptive coping strategies.11 The potential of improved resilience in advancing recovery and rehabilitation12—that is, diminishing functional signs and symptoms such as fatigue—is considerable. Comprehensive rehabilitation aimed at strengthening the factors that promote resilience will presumably improve an individual's ability to adapt to a set of conditions. Yet, little has been written that focuses on how environmental interventions that approximate real-life behaviors in context can be used to affect resilience. Therefore, this pilot study was designed to determine whether a standard course of occupational therapy (OT) coupled with other interventions in a variety of disciplines can influence resilience in individuals with MS.

Study Purpose

This pilot study was designed to address the following question: Can resilience in individuals with MS be influenced by standard multidisciplinary treatment approaches that include OT intervention aimed at enabling independent function and participation? The specific purpose of this study was to examine whether participation in a multidisciplinary treatment program provided by an MS center will affect resilience. A secondary purpose, which emerged as participants did or did not follow through with their referrals, was to see if those who participated in OT in addition to other modes of treatment had better resilience than those who did not participate in OT.

Methods

Research Design

This pilot study was set up using a quasi-experimental design, with pretest and posttest measures of resilience. All participants were patients at the MS center and were receiving the usual treatments provided by an MS multidisciplinary team. The multidisciplinary team is set up to facilitate both written and verbal communication among the professionals who serve each patient. The patient's physician makes the referrals for the services needed. While information regarding the patient's progress is shared, goal setting remains within the purview of each discipline. This is consistent with how multidisciplinary teams, in contrast to interprofessional and trans-disciplinary teams, are defined.13

All participants were referred to OT specialists as part of their treatment, as well as to specialists in physical therapy, psychology, and social work. In addition, they attended sessions with their neurologist and nurse.

Our respective university institutional review boards approved this study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Resilience Instruments

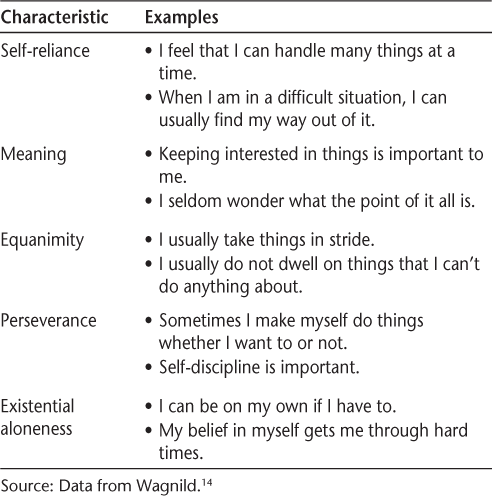

Built upon a construct that addresses one's ability to endure and persist despite hardship or challenge, the Resilience Scale (RS) was first developed in 1990 as a way to measure resilience in individuals who were able to adjust successfully after a major life event.5 It has since been applied to a variety of populations, from adolescents to the elderly, with diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds and conditions.7 14 The RS is a 25-item, self-report, 7-point Likert scale based on five characteristics of resilience that are related to “acceptance of self and life” and “personal competence”: self-reliance, meaning, equanimity, perseverance, and existential aloneness. 14 Table 1 provides examples from the RS that relate to each of these characteristics. Internal consistency for the RS was reported to be strong (r = 0.91, P < .001); concurrent validity was measured against assessments related to relevant constructs, such as life satisfaction, morale, depression, and health, with significant correlations at the P < .001 level.5 Although there is no “gold standard” for measures of resilience, the RS has been noted to be among the strongest instruments with construct validity, and is the most applicable to a variety of populations.15 It has also been used as a test-retest measure of resilience.16

Characteristics and examples of Resilience Scale statements

The 25 items of the RS reflect characteristics related to personal strengths, purposefulness of life, adaptability, willingness to persist, and individualism.14 Ratings on each of the items are tallied for a raw score that can range from 25 to 175. Scores of 120 or below represent low resilience; scores of 121 to 145 represent low-moderate resilience; scores of 146 to 160 represent moderately high resilience; and scores above 160 represent high resilience.14

Participant Selection

All patients who were referred for OT as part of their multidisciplinary treatment at a large, northeastern metropolitan MS center were invited to participate. The center provides multidisciplinary comprehensive care, rehabilitative services, and client-oriented programs to improve quality of life. Inclusion criteria for this study were a diagnosis of definitive or probable MS and ability to speak, write, and read English. Excluded from participating in the study was any patient with severe cognitive impairment, Axis I clinical disorders, or Axis II personality disorders; who was unwilling to follow or incapable of following the protocol procedures; or who had experienced a relapse within the past 30 days.

Thirty-six patients initially provided informed consent to participate in the study. All patients referred for OT were experiencing impairments in their daily functioning due to specific MS symptoms. Each of the 36 patients was expected to meet regularly with his or her physician and follow through with referrals to other disciplines including OT, physical therapy, nursing, social work, and psychology. Initial data from any individual who did not maintain his or her appointments with at least one member of the multidisciplinary team during the 8-week period would be eliminated from the study.

Intervention

All participants received the usual and customary multidisciplinary intervention provided at the MS center. Each patient's multidisciplinary treatment was tailored to meet the individual's specific needs. The primary treatment that all participants received during the 8-week study period was from their MS neurologists. All participants were referred for OT, which focused on adapting to symptoms that were interfering with functioning. All participants were also referred for services provided by the other members of the multidisciplinary team at the center, depending on their respective needs. These other services included physical therapy, which focused on gait and ambulation; nursing and neurologist visits, which focused on symptom management; social work sessions, which focused on housing and insurance difficulties; and psychology sessions, which focused on emotional issues.

Data Collection and Analysis

Participant involvement in the multidisciplinary treatment was ongoing, and all participants filled out questionnaires used for data collection. Data were collected at the time of the patient's initial OT evaluation and prior to the OT intervention using a demographic questionnaire developed for this study along with the RS.5 After 8 weeks, participants were asked to complete the RS again. Treating personnel of all disciplines had no knowledge of the pretest and posttest results of the RS. Scores on the RS were computed in order to monitor change in score. These scores were also categorized from low to high resilience in order to monitor change in resilience level.

After study completion, statistical calculations were performed using SPSS, version 18 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), in order to examine variables that may be associated with resilience and to determine changes in resilience over time. In addition to descriptive data, nonparametric calculations were used with nominal and ordinal data, and parametric calculations were used with interval data. Effect size, which measures the strength of the difference or association in groups and is a meaningful adjunct to tests of significance,17 was also calculated using appropriate Cohen's d formulas.18 The interpretation of effect size was based on the value of Cohen's d.17

Results

Participation in Multidisciplinary Treatment

Of the initial 36 participants who provided informed consent, only 1 did not follow through with any referrals or fill out the RS after 8 weeks. This participant was lost to follow-up and excluded from the sample. The results of this pilot study are based on the remaining sample of 35 people.

All participants in the study were initially seen by a neurologist specializing in MS, who then made the referrals to members of the multidisciplinary team. Most participants received one to two treatment sessions from each of the disciplines other than OT. The total number of sessions with these related disciplines averaged 7, with a range of 1 to 18.

Of the 35 participants, 26 individuals fully engaged in their OT program, participating in 10 to 12 scheduled sessions over the 8-week period. Nine individuals, after attending the first OT session, decided not to participate in OT because of scheduling difficulties (n = 4), transportation problems (n = 2), or reluctance to pursue treatment (n = 3). This self-selected group kept their appointments with other members of the treatment team and filled out the RS 8 weeks after their initial visit.

Demographic Data

Demographic information for all 35 participants was compiled, including data on age, number of years since diagnosis with MS, gender, race, income, and education (Table 2). Income was categorized both ordinally and by whether it was below or above the city's median income level.

Demographic information

Initial Measure of Resilience

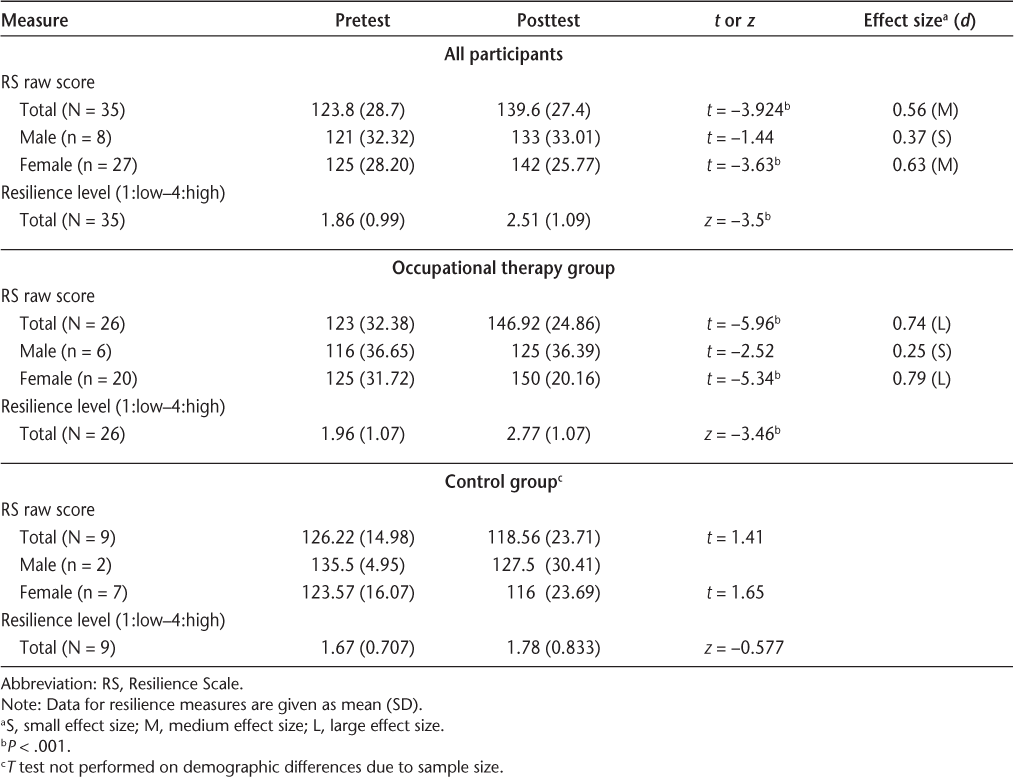

The resilience score and the resilience level were calculated using the procedure outlined in the RS manual.14 The average resilience score for the 35 participants at the beginning of the study fell in the low-moderate range (Table 3).

Change in measures of resilience from pretest to posttest

Differences in resilience scores based on demographic information were examined using the independent-samples t test and with equal variance assumed using Levene's Test for Equality of Variances. No statistically significant differences in resilience were found between men and women (t = −2.37, P = .746) or between those whose income was at or below the city's median income level and those with income above the median level (t = 1.65, P = .108). Spearman's rho showed a significant correlation of income level and raw score prior to treatment (r = 0.369, P < .05), with those with higher incomes showing more resilience. The effect size was small (d = 0.14). The correlation of income with resilience was not significant after treatment (r = 0.03, P = .874).

After 8 weeks of multidisciplinary treatment, resilience was measured again in all 35 participants (Table 3). Using the paired-samples t test, resilience significantly improved in raw score (N = 35, t = −3.924, P < .001) with a moderate effect size (d = 0.56). Resilience improved significantly for women over the 8-week period. While it also improved for men, the change was not significant.

OT Treatment and Control Groups

At the beginning of the study, nine participants elected not to participate in OT despite their referral based on need. They did continue with all other referrals and filled out the RS after the 8-week period of multidisciplinary treatment. Using the chi-square or Mann-Whitney test where appropriate, the self-selected sample that did not participate in OT showed no significant difference in demographic data compared with the OT treatment group. There was also no statistically significant difference between these two groups in the number of sessions they attended with their other health-care team members. For these reasons, the group of individuals who did not participate in OT can be considered a control group, although determined ad hoc. The OT treatment group (n = 26) and control group (n = 9) merit separate examination.

OT Treatment Group

Spearman's rho was calculated in order to determine whether any relationship existed between specific demographic data (such as income level, education level, and number of individuals in one's support system) as well as between demographic data and resilience measures in those who participated in OT for the 8 weeks. One significant correlation was found: one's level of resilience prior to treatment correlated with the number of people in one's support network (r = 0.427, P < .033, d = 0.65). This correlation was not significant after the 8 weeks of treatment.

The independent-samples t test was used to determine whether resilience differed based on characteristics such as gender, income level, and relationship status. Individuals who were married or partnered showed higher resilience on the initial RS test than those who were not married or partnered (t = −2.305, P < .05). This distinction in resilience was not found after the 8 weeks of treatment. When considering one's living arrangement without regard to marital status, those individuals who lived with a family member or friend/roommate had significantly higher resilience than those living alone. This result was found on both the initial RS test (t = −3.737, P = .001) and after the 8 weeks of treatment (t = −3.062, P = .05). There were no differences in resilience before or after treatment based on gender or income level.

For all participants who completed their OT treatment, the paired-samples t test showed statistically significant improvement in their RS scores (t = −5.96, P < .001) as compared with their scores when they first enrolled in the pilot study; Cohen's d showed a large effect size for this difference (d = 0.74). Resilience improved in both men and women. However, the men only trended toward significance (t = −2.52, P = .053), with a small effect size (d = 0.25), while the women improved significantly, with a large effect size (t = −5.34, P < .001, d = 0.79) (Table 3). The same finding resulted when using nonparametric statistics for level of resilience; that is, when resilience was categorized from low to high levels.

Control Group

Unlike in the OT treatment group, in the control group no relationship was found within any of the demographic data, nor did demographic data such as income correlate with any measure of resilience (r = 0.5, P = .17). Distinctions in resilience based on demographic characteristics such as gender, median income level, and social network could not be calculated owing to the limited number of participants.

Differences in pretest and posttest measures of resilience were examined using the t test. Although the average score on the RS for those in the control group decreased after the 8-week period, the difference was not significant (Table 3). When examining pretest and posttest resilience scores by gender, scores decreased for both males and females. Difference between pretest and posttest based on gender could not be analyzed with the t test for males, as the number was too small. For females, however, the difference was not significant.

Cross-Group Comparisons

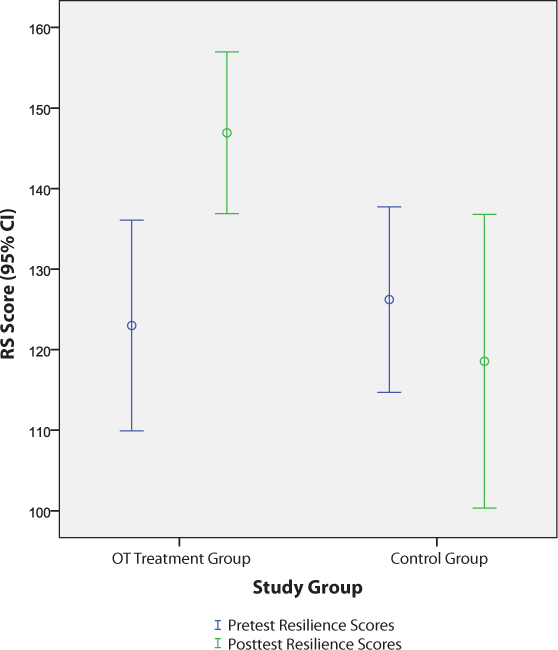

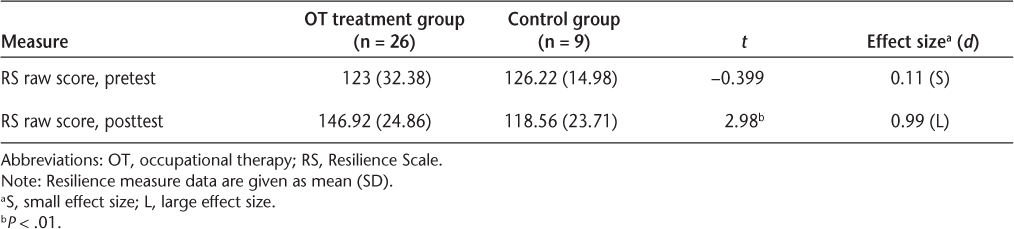

The average raw scores on the RS before and after the 8-week period for the OT treatment group and for the control group (with the confidence interval set at 95%) are shown in Figure 1. When comparing the initial RS scores for the OT treatment group and the control group, no significant difference was found (equal variance was not assumed, using Levene's Test for Equality of Variances). After the 8-week period, we found that the OT treatment group's resilience increased significantly, the control group's resilience decreased, and there was a significant difference between these outcome measures (equal variance was assumed using Levene's Test for Equality of Variances). The raw scores showed a significant difference (t = 2.98, P < .01), with a large effect size (d = 0.99) (Table 4).

Mean raw Resilience Scale scores (with 95% confidence intervals) before and after 8-week period for OT group and control group

Pretest and posttest resilience measures for OT treatment group vs. control group

Discussion

This pilot study suggests that resilience in individuals with MS can be enhanced by using a multidisciplinary, client-centered approach to treatment. Each patient was treated according to the specific MS symptoms that were interfering with his or her functioning and participation in meaningful activities. This is consistent with findings that individualized treatment focusing on problem solving, social support, and engagement in daily activities promotes resilience in the MS population.19 The comprehensive treatment approach should include attention to symptoms that affect community participation, such as fatigue, mobility, coping, and social and emotional issues.

Resilience may play a significant role in functional outcomes20 and affect participation.21 22 If one considers resilience from the perspective of attributes that promote adaptation, such as being able to rebound from adversity, reintegrate into one's regular routine, and maintain flexibility,2 the implications are apparent. As Ann Masten concluded: “Resilience does not come from rare and special qualities, but from the everyday magic of ordinary, normative human resources in the minds, brains, and bodies of [people], in their families and relationships, and in their communities.”9 (p235)

It has been documented that environmental factors such as poverty and factors related to social support are linked to resilience.23 In our study, we found that income level correlated with resilience prior to treatment and may have a general impact on resilience, as it may afford one the opportunity to access helpful resources. We also found that social factors such as support networks correlated with pretreatment scores of resilience in those individuals who participated in OT. As these were noted prior to treatment, it is possible that resources may have a mediating effect on resilience. Because these correlations were not significant after multidisciplinary treatment, factors related to financial or social resources may become less instrumental in enhancing resilience as a result of the improvement of one's personal abilities and capabilities. This does not, however, discount the important role that support systems may play in resilience.

The relationship of social factors to resilience in challenging situations has been noted in the literature.24 Indeed, loneliness and social isolation have been reported to be prevalent in the MS population.25 In our study, there was a relationship between social factors (ie, number of individuals in one's network and partnered/marital status) and resilience prior to OT treatment: the more limited one's social involvement, the less resilient one was. It has already been documented that social support relates to perceived health status in this population.26 Social networks, in the form of assistance or friendship, may allow for interaction that is both technically and emotionally helpful. Because social factors relate to community participation, their role in perceived ability to function and deal with challenges cannot be overstated. It is not surprising, therefore, that those with stronger social networks had higher resilience prior to treatment. A perhaps more compelling finding from our study is that after treatment there was no longer a difference in resilience based on social factors. Thus, the effect of intervention aimed at helping a person meet the challenges that arise from having a disability and enabling participation through community reintegration is considerable.

Some gender differences in resilience were found. Just over three-quarters of our entire study sample consisted of women. Women's resilience overall and in both the OT treatment group and the control group improved significantly. Men's resilience in these two cohorts also increased, but not significantly. The small sample size of men may account for the nonsignificance of the improvement. However, studies have identified the multiple roles women have and their opportunities to engage in social networks as being linked with resilience.27 Social factors also played an important role in our study, possibly accounting for women's improvement in resilience.

Resilience in the MS population may be specifically vulnerable to individual factors such as cognitive ability and fatigability. Cognitive dysfunction, for example, can have a significant impact on psychosocial variables such as job performance and overall quality of life.28 Both relate to challenges in daily activities, and both further limit social interaction. Resilience relates to adaptability, and adapting to challenges includes the ability to adopt alternative strategies. Adaptation is a function of cognition and of coping29 and plays a role in one's ability to maintain independence and participation.30 Even though our population did not have severe cognitive deficits, how one uses cognitive strategies may influence psychological adjustment and be more influential than health-related variables.31

These three areas—cognitive ability, fatigue, and social participation—along with a focus on how individuals with this disease can continue to participate in their meaningful activities and life roles are the focus of the OT component of the MS center's multidisciplinary services, and may account for the improvement in resilience found. The focus of the OT treatment is also consistent with those characteristics embedded in Wagnild's14 constructs of resilience described earlier.

There is limited evidence of the general effectiveness of OT in individuals with MS.32 While some studies suggest that interventions aimed at one's ability to complete activities, such as those related to daily living,33 or education-based programs aimed at energy conservation that can result in improved quality of life34 are effective, more evidence-based research is needed.

This study was initially designed as a pilot program to examine the impact of a multidisciplinary treatment approach on resilience. Although determining the specific effect of OT on resilience was not the initial intent of the study, the emergence of a control group provided an opportunity to compare resilience in two subgroups that were coincidentally matched on a number of important variables. The observation of differences in outcomes between the groups that did and did not participate in OT provided insight into the role that OT plays in fostering resilience.

The results indicated that resilience in individuals who received OT was significantly better than that in those who did not receive OT. Participants who received OT had a significant improvement in resilience scores from pretest to posttest, while most in the control cohort experienced a decrease in resilience after the 8-week period and remained at the low–low moderate level. The OT program specifically addressed community reintegration and socialization, functional performance in daily activities and life roles, coping strategies, patient education, and symptom management.

While some authors consider resilience to consist of traits that are inherent and stable over time,1 3 others support the notion that resilience is subject to modification.12 Our results support the latter concept that resilience can be developed. Distinguished from recovery, which implies a change in symptoms over time, resilience encompasses factors and/or skills that enable an individual to positively adapt in the face of adversity.35 Resilience, therefore, may result from one's emotional, physical, and social functioning that allows one to adapt to challenging situations in ways that permit participation and prepares one to deal with future challenges. Our pilot study supports the concept that resilience is pliable.

Limitations

This study was carried out in a center specifically designed to treat people with MS. Results from this study cannot be generalized to other MS populations, or to other populations treated by multidisciplinary teams that include occupational therapists. The results should be interpreted with the understanding that this was a pilot study with a limited sample size and consequently low statistical power.

Caution must be used when interpreting these results. Participants attended sessions with all members of their health-care team, but they had the greatest exposure to OT. It is not known how resilience would have been affected if participants had attended equal numbers of sessions with all health-care providers. Although the number of sessions received was based on the needs of each individual, the impact these modalities had on resilience is not fully understood. It is also not known if the improvement in resilience is related to the added attention these participants received. While members of both groups attended similar numbers of sessions with their non-OT health-care providers, because members of the OT treatment group also participated in OT, they spent significantly more hours overall with the health-care team.

This study's control group was determined ad hoc. Although this is acceptable, it would have been preferable to designate randomized OT treatment and control groups, for the groups to be matched in size, and for each group to have equal numbers of men and women.

Areas for Future Research

This pilot study raises additional questions that may be addressed through future research. The RS consists of 25 statements addressing different conceptual components of resilience. Exploring which components are most influential in this population is an area for future research. Additional areas for study include the relationship between resilience and quality of life; the specific impact of OT on resilience, using an experimental design; and the role of coping strategies embedded in an OT program and their effect on resilience. It would also be interesting to measure the durability of the improved resilience of the OT treatment group 6 months after discharge from OT.

Conclusion

The results of this pilot study suggest that multidisciplinary treatment teams, particularly with the inclusion of OT, can improve the resilience of MS patients. Programs that focus on improving functional performance in daily activities and life roles—especially when coping strategies, patient education, and symptom management are included—seem to be beneficial. In addition, community reintegration programs and socialization groups that promote developing support systems may also contribute to one's resilience. Enhanced resilience can have a beneficial impact on patients with MS, and if participation in OT leads to improved resilience, OT practitioners should be part of the multidisciplinary team caring for people with MS.

PracticePoints

Resilience, or the capacity for positive adaptation in response to stress or adversity, plays an important role in functional recovery and maintenance in people with MS.

A multidisciplinary approach to treatment can improve resilience in those with MS.

Occupational therapy may be an especially critical component of multidisciplinary treatment for people with MS in improving resilience.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joseph Herbert, Director of the MS Care Center at NYU Langone Medical Center, and the patients who participated in this study. Without their support the study could not have been completed.

References

Atkinson P, Martin C, Rankin J. Resilience revisited. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009; 16: 137–145.

Earvolino-Ramirez M. Resilience: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2007; 42: 73–82.

Jacelon C. The trait and process of resilience. J Adv Nurs. 1997; 25: 123–129.

Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity—protective factors and resistance to psychiatric-disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1985; 147: 598–611.

Wagnild G, Young HM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas. 1993; 1: 165–178.

Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000; 71: 543–562.

Wagnild G. A review of the Resilience Scale. J Nurs Meas. 2009; 17: 105–113.

Tusaie K, Dyer J. Resilience: a historical review of the construct. Holistic Nurs Pract. 2004; 18: 3–8.

Masten AS. Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001; 56: 227–238.

Greene R, Galambos C, Lee Y. Resilience theory: theoretical and professional conceptualizations. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2003; 8: 75–91.

Yi-Frazier JP, Smith R, Vitaliano P, et al. A person-focused analysis of resilience resources and coping in patients with diabetes. Stress Health. 2010; 26: 51–60.

White B, Driver S, Warren AM. Considering resilience in the rehabilitation of people with traumatic disabilities. Rehabil Psychol. 2008; 53: 9–17.

Jessup RL. Interdisciplinary versus multidisciplinary care teams: do we understand the difference? Aust Health Rev. 2007; 31: 330–331.

Wagnild G. The Resilience Scale: Users Guide for the US English Version of the Resilience Scale and the 14-Item Resilience Scale (RS-14). Worden, MT: The Resilience Center; 2009.

Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011; 9: 1–18.

Schachman K, Lee RK, Lederman RP. Baby boot camp: facilitating maternal role among military wives. Nurs Res. 2004; 53: 107–115.

Kotrlik J, Williams H. The incorporation of effect size in information technology, learning, and performance research. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal. 2003; 21: 1–7.

Carlson KD, Schmidt FL. Impact of experimental design on effect size: findings from the research literature on training. J Appl Psychol. 1999; 84: 851–862.

Mohan N. Examining the Nature of Resilience and Executive Functioning in People with Brain Injury and People with Multiple Sclerosis [dissertation]. Adelaide, Australia: Disability and Community Inclusion, School of Medicine, Flinders University; 2010.

Fine SB. Resilience and adaptability: who rises above adversity? Am J Occup Ther. 1991; 45: 493–503.

Law M. Distinguished scholar lecture: participation in the occupations of everyday life. Am J Occup Ther. 2002; 56: 640–649.

Lopez A. Posttraumatic stress disorder and occupational performance: building resilience and fostering occupational adaptation. Work. 2011; 38: 33–38.

Rutter M. Resilience: some conceptual considerations. J Adolesc Health. 1993; 14: 626–631.

Bonanno G, Mancini A. The human capacity to thrive in the face of potential trauma. Pediatrics. 2008; 121: 369–375.

Beal CC, Stuifbergen A. Loneliness in women with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Nurs. 2007; 32: 165–171.

Krokavcova M, van Dijk JP, Nagyova I, et al. Social support as a predictor of perceived health status in patients with multiple sclerosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2008; 73: 159–165.

Moen P, Dempster-McClain D, Williams RM Jr. Social integration and longevity: an event history analysis of women's roles and resilience. Am Sociol Rev. 1989; 54: 635–647.

Rao SM, Leo GJ, Ellington L, Nauertz T, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. II. Impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology. 1991; 41: 692–696.

Montel S, Bungener C. Coping and quality of life in one hundred and thirty five subjects with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 393–401.

Goretti B, Portaccio E, Zipoli V, et al. Coping strategies, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2009; 30: 15–20.

McCabe M, McKern S, McDonald E. Coping and psychological adjustment among people with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2004; 56: 355–361.

Steultjens EM, Dekker J, Bouter LM, Cardol M, Van de Nes JC, Van den Ende CH. Occupational therapy for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD003608.

Baker NA, Tickle-Degnen L. The effectiveness of physical, psychological, and functional interventions in treating clients with multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Am J Occup Ther. 2001; 55: 324–331.

Mathiowetz VFM, Matuska KM, Chen HY, Luo P. Randomized controlled trial of an energy conservation course for persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 592–601.

Bonanno G. Loss, trauma, and human resilience. Am Psychol. 2004; 59: 20–28.

Financial Disclosures: Ms. Kalina is employed at the center where the data were collected. Dr. Falk-Kessler and Ms. Miller have no conflicts of interest to disclose.