Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Exploring Adherence to First-Line and Second-Line Immunotherapies in Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Treatment adherence is fundamental in multiple sclerosis (MS) management. Adherence rates vary significantly between studies, ranging from 30% to almost 90%, depending on assessment method and medication type. This study aimed to identify patient-related categories associated with treatment modification or discontinuation in people with MS receiving either first- or second-line treatment.

Methods:

Semistructured interviews were performed with 23 people with MS: 11 receiving first-line treatment and 12 receiving second-line treatment. Medication history, experiences with previous medications, decision-making processes regarding immunotherapy, adherence behavior, and reasons for adherence/nonadherence were explored using open-ended questions. Qualitative content analysis was performed using a combined deductive-inductive approach in building a coding frame. Differences in coding frequencies were compared between the two groups and analyzed quantitatively. Cohen’s kappas of 0.76 for people with MS receiving first-line treatment and 0.64 for the second-line sample were achieved between the two coders.

Results:

One key reason for nonadherence reported by first-line–treated people with MS was burdensome side effects, and for adherence was belief in medication effectiveness. In people with MS receiving second-line treatment, lack of perceived medication effectiveness was a key category related to changes in or discontinuation of immunotherapy. Reasons for adherence were positive illness beliefs/perceptions and belief in highly active disease. Intentional nonadherence was a major issue for first-line treatment and less relevant for second-line treatment.

Conclusions:

These results indicate specific differences in factors mitigating adherence in people with MS receiving first- and second-line treatment.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammation of the central nervous system and is most prevalent in early and middle adulthood.1 There is no curative treatment available. Consequently, patients with MS only have the opportunity to either take no medication or select a treatment that aims to attenuate disease progression.2 If a first-line treatment fails, a second-line treatment is available with higher efficacy and possibly higher risk.

In recent years, the number of drug treatment options for MS has substantially grown. As in other chronic neurologic diseases, adherence can significantly affect treatment outcomes as well as costs.3 According to the World Health Organization,4(p17) adherence is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behaviour – taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider.” In people with MS, relapse or disease progression seems more prevalent in patients nonadherent to treatment.5 In addition, lower medication adherence is associated with increased health care resource utilization.6,7

A recent study reported high rates of adherence in people with MS of up to 90%,8 but several international studies are less optimistic and report adherence rates of no more than 60%.6,7,9 Data from a sample of German statutorily insured people with MS even found adherence rates of only 30% to 40% two years after initiating MS-modifying treatment.10 These latter studies also stress caution about the burden of nonadherence on the health care system. Thus, for clinical and economic reasons, it is important to identify factors that influence treatment adherence, which then may be addressed during the treatment process.11

Factors influencing treatment adherence across different diseases have been described in various studies.12 To systematically investigate these factors, Zwibel and colleagues13 performed a study in people with MS based on Prochaska’s transtheoretical model of change. They suggest a distinction between 1) patient-related factors, such as low self-efficacy, and 2) treatment-related factors, such as adverse effects. Factors influencing treatment have been identified for injectable treatments, but little is known for oral treatments and second-line therapies.5,14 Forgetting to inject, perceived lack of efficacy, fear of injections, and adverse effects, especially injection-site reactions, flu-like symptoms, and fatigue, are major reasons for nonadherence in studies about injectable treatments.5 Other studies additionally focus on interactional factors, such as the decision-making process or the physician-patient relationship.15 The provision of information is another potential factor that seems to be associated with treatment adherence.16

Differences between people with MS receiving first- and second-line treatment in disease activity and drug characteristics are also likely to influence adherence rates,17 but so far no study has explored first- and second-line treatment adherence characteristics. The aim of the present study was to investigate factors influencing treatment adherence and nonadherence in people with MS receiving either first- or second-line treatment.

Methods

Study Design

This exploratory qualitative study comprised face-to-face and telephone interviews with people with MS receiving either first- or second-line treatment. We aimed to include individuals who already had experiences with a change in medication, either having stopped or having switched to another treatment. The ethical review board of the Hamburg Chamber of Physicians approved the study.

Sample

The concept of purposeful sampling18 was used to identify people with MS. The inclusion criteria for people with MS receiving first-line treatment were 1) a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), 2) current treatment with teriflunomide or dimethyl fumarate, and 3) past therapy with a minimum of one other first-line treatment. The inclusion criteria for people with MS receiving second-line treatment were 1) a diagnosis of RRMS; 2) current treatment with natalizumab, alemtuzumab, or fingolimod; and 3) past therapy with a minimum of one other first- or second-line treatment. It was decided to focus on people receiving oral treatments in the first-line treatment group to have a homogenous sample with presumably injectable treatment experiences in the past and, thus, being able to reflect on adherence issues from their experiences with two drugs. Patients with language or cognitive impairment were not included, according to clinical judgment. People with MS were recruited through databases and mailing lists, as well as the newsletter of the MS outpatient clinic of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany and an announcement on the regional MS society’s website.

Data Collection

Informed consent was obtained from all people with MS before data collection. Interviews were conducted by one of three psychologists (B.U. and the research assistants K.L. and T.R.) face-to-face or via telephone at the MS outpatient clinic of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. The interviews were conducted using a semistructured interview guide (see Table S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org, for the abbreviated guide) based on previous adherence studies.12–15 The interviews lasted approximately 50 minutes and were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using inductive and deductive qualitative content analysis, following the method of Mayring.19 Analysis was based on units of coding as the smallest amount of words that could be interpreted in a meaningful way. T.R., K.L., and B.U. worked on the material as coders, defining coding units and ordering them into deductive, theory-based and inductive, data-driven categories. In a first step, T.R. and K.L. analyzed the interviews of people with MS receiving first-line treatment starting from five adherence theory–based main categories (Appendix S1, part A): 1) type of nonadherence (intentional and unintentional), 2) reasons for nonadherence (attitudes toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control), 3) handling of nonadherence (active or passive), 4) factors that could have had a positive influence on adherence, and 5) reasons for adherence (attitudes toward adherence behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control). In a second step, subcategories were defined based on adherence and decision-making theory, leading to 35 categories.

In a third step, category definitions, anchor examples illustrating the main categories, and coding rules were formulated. As a fourth step, transcripts were examined and coding units fitting the defined categories were extracted. After jointly categorizing 20% of the material, the researchers analyzed the remaining 80% of the material independently (fifth step). Next, T.R. and K.L. worked on reaching consensus concerning the categorization by discussing, adjusting, and refining the coding categories as well as the coding rules (sixth step). Finally, the coding frame was systematically structured (seventh step). After analyzing first-line interviews, 37 categories were defined, two of which were added to the deductive construct, while both coders independently concluded that these factors are not represented in the category frame.

After analysis of the first-line treated cohort, interviews with second-line–treated people were analyzed, and two independent coders (T.R. and B.U. as a new researcher) revised the category system again, leading to three new categories based on the consensus of both coders. The final category system consisted of 40 categories referring to 21 main categories (Appendix S1, part B). Cohen’s kappa was calculated as a measure for interrater reliability across all the main categories. The interrater reliability (T.R., K.L., B.U.) in the present study was satisfying (people with MS receiving first-line treatment: proportional agreement [T.R. and K.L.] = 73%, Cohen’s kappa = 0.76; people with MS receiving second-line treatment: proportional agreement [T.R. and B.U.]: 71%, Cohen’s kappa = 0.64).

Subsequently, a descriptive quantitative analysis was performed because the coding frequencies of categories and subcategories may give weight to its importance and meaning.19 For all the categories mentioned by all the respondents, coding units in the two subgroups referring to the respective category were counted. This procedure followed the premise that more frequently cited categories are also of higher significance for therapy adherence. Descriptive statistics were reported as either medians (ranges) or absolute numbers (percentages).

Results

Sample Characteristics

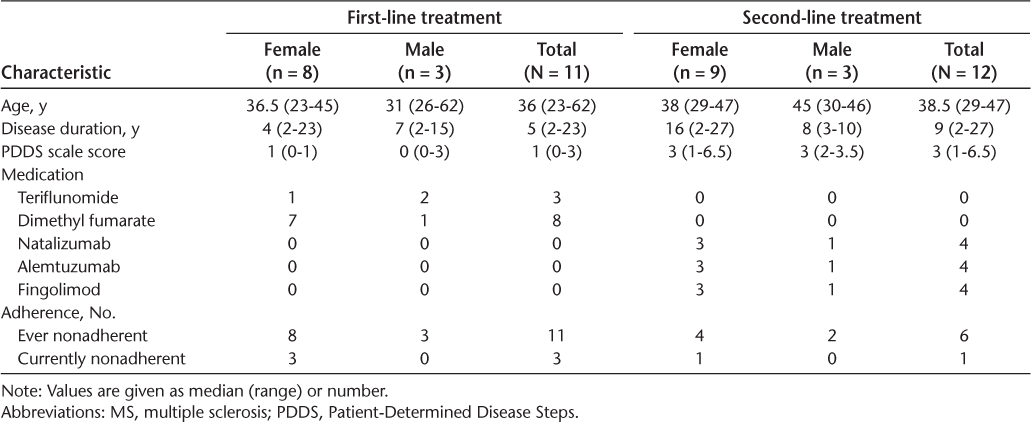

A total of 23 people with RRMS—11 receiving first-line treatment and 12 second-line treatment—with a wide range of ages (23–62 years) and disease durations (2–27 years) were included.

Table 1 gives an overview of the two groups regarding demographic and clinical data. Main categories as well as exemplary quotations are reported in the following sections for people with MS receiving either first- or second-line treatment.

Demographic and clinical data of the people with MS receiving either first- or second-line treatment

People with MS Receiving First-Line Treatment

Reasons for Adherence

Belief in medication effectiveness was one of the major factors reported by people with MS receiving first-line treatment, who not only reported that they generally believed in treatment effectiveness but also discovered worsening of symptoms, which confirmed the impression of the effectiveness: “I always had the belief that it is helpful” (participant with MS receiving first-line treatment 10 [1-L P10]). Another category that was referred to by several people with MS was belief in highly active disease. People with MS reported to be afraid of relapses or worsening of symptoms, which was the reason for continuing immunotherapy: “I’m afraid that the interval between relapses could become shorter or that symptoms increase in a way that I do not want to continue living with them” (1-L P9). Some participants reported ways of coping with medication adverse effects, which facilitated continuation of the treatment: “I found a way to cope with the side effects” (1-L P11). The absence of everyday life restrictions/absence of illness reminders was of additional importance: “It’s quite comfortable to take a pill twice a day; you can just integrate this into your daily routine and do not have to think about your disease intensively” (1-L P2).

Reasons for Nonadherence

Several participants reported burdensome side effects as a reason for nonadherence: “The side effects were just too strong” (1-L P5). Experienced burden of treatment management beyond side effects was also a relevant factor (category: restrictions in everyday life: “…you are quite inflexible when you have to take this medication” [1-L P5]). In some people with MS, nonadherence was found to be unintentional: “I think I just forgot it during this period once or twice in the morning” (1-L P1), whereas nonadherence that occurred intentionally was also present: “When I came home at 3 am I was already drunk and knew that I would have to throw up” (1-L P6). Psychological barriers or a low self-efficacy describes another important factor: “Due to my injection phobia, this was pure horror. Whenever I had to inject the medication; this bothered me most” (1-L P1). The interviews revealed that people with MS who did not have belief in the effectiveness of the medication were more likely to be nonadherent (category: lack of belief in effectiveness/burdensome side effects: “I took the medication for 2.5 years and still got more lesions” (1-L P6). In addition, the application type was another significant factor: “She explained everything to me and then it was quite clear to me that I’d rather take a pill than have an injection” (1-L P9). Experience of low disease activity leading to belief in a benign disease was another relevant factor: “I discontinued it, because I didn’t have symptoms for a long time” (1-L P11).

People with MS Receiving Second-Line Treatment

Reasons for Adherence

Comparable with results for people with MS receiving first-line treatment, belief in medication effectiveness was a major factor related to adherence: “I wanted to be sure that I’m protected” (participant with MS receiving second-line treatment 8 [2-L P8]). Responsibility for others was another aspect highlighted by several second-line–treated people with MS: “If the children wouldn’t have been there, I would have stopped fighting so hard” (2-L P4). No restrictions of daily life also had a positive effect on adherence: “For me it’s the nice thing with the medication, and I really have to stress that I prefer a fixed appointment with my neurologist every 2 or 3 months instead of having to inject myself every day” (2-L P6). Another aspect considered relevant was trust in physician: “My neurologist comforted me… and I have to admit that I really have trust in her” (2-L P3). Perceived behavioral control or self-efficacy belief was as well considered relevant: “I told myself, take a deep breath and get to it; you can make it” (2-L P9).

Reasons for Nonadherence

Lack of belief in medication effectiveness was reported as a major reason for nonadherence: “Obviously, there wasn’t much of improvement” (2-L P5). The issue of side effects was another important facet: “Yes, a very toxic agent. My body weight dropped to 42 kilos” (2-L P5). A category that was particularly reflected in the statements of second-line–treated people with MS was the negative attitude of the environment of the people with MS, including physicians: “Yes, Prof. … and I discussed about my medication and he advised me not to continue the use. It seemed that it didn‘t help” (2-L P10). Another factor, which was also highlighted in first-line–treated people with MS, was unintentional nonadherence: “Yes, it could be that I forgot to take it once in a while” (2-L P2).

Quantitative Analysis

The first two interviewed people with MS receiving first-line treatment were excluded from the quantitative analysis because they initially served to inductively generate categories. There were seven categories coded for all first-line and ten for all second-line participants. The quantitative analysis of the first-line interviews was based on a total of 803 coding units of reasons for nonadherence/adherence. Frequency distributions of main reasons for nonadherence across all respondents are displayed in Table S2. Burdensome side effects was the most assigned category (9.6% of all analyzed coding units) in people with MS receiving first-line treatment, constituting the main reason for nonadherence. However, even less often attributed categories, such as adequate decision-making process (4.73%), were contributed to by all nine people with MS receiving first-line treatment.

In the group of people with MS receiving second-line treatment, 1186 coding units were differentiated in the interviews. All 12 people with MS receiving second-line treatment reported a lack of belief in medication effectiveness (4.13% of all elements) and a negative attitude toward medication in the social environment (3.46%). The main reasons for adherence/nonadherence in second-line–treated people with MS are displayed in Table S3.

A comparison of mainly cited elements between people with MS receiving either first- or second-line treatment is displayed in Table S4. The distribution pattern differed between the two groups, indicating different reasons for adherence/nonadherence in the two groups. There were fewer codings referring to intentional nonadherence in people with MS receiving second-line treatment, who more frequently reported that belief in highly active disease affected their adherence. They also more often reported to be adequately supported concerning treatment implementation and more frequently felt supported by or responsible for others, such as family members. People with MS receiving second-line treatment more often had trust in their physicians and their advice. People with MS receiving first-line treatment reported burdensome adverse effects more often than did those receiving second-line treatments.

Discussion

The present study addressed reasons for adherence and nonadherence in people with MS receiving either first- or second-line treatment. It focused on potential differences between these two groups. In people with MS receiving first-line treatment, the main reasons for adherence/nonadherence referred to categories related to the treatment itself, such as adverse effects or attitudes toward effectiveness. This has also been described in other studies.20,21 The importance of adverse effects is also in line with a representative study performed by Devonshire and colleagues,22 who found medication-related reasons to be the second most common reason (32%) for nonadherence in people with MS, following “forgetting to administer the injection” (50%). Giovannoni and colleagues15 confirmed these factors in a systematic review and identified flu-like symptoms in interferon therapies as well as injection-site reactions as the most common adverse events influencing treatment adherence. In addition, the content of the treatment information and its provision in the decision-making process seemed to be of major importance for adherence behavior in the present study.

In people with MS with second-line treatment, belief in highly active disease and belief in drug efficacy seemed to be the most prominent factors in relation to adherence. Interestingly, adverse effects were considered less relevant. Overall, most of the people with MS receiving second-line treatment reported satisfaction with the decision-making process, even those who felt forced into treatment. Some respondents argued that they were overwhelmed by the diagnosis and not able to make decisions at all but were able to reevaluate the decision and change treatment after some time. Following physician advice at the initial stage of the treatment process might represent a coping strategy in people with MS who do not feel able to make adequate decisions after a recent diagnosis.

Many studies have demonstrated that a large percentage of people with MS prefer an autonomous or shared decision-making process.23,24 However, whereas people with MS receiving first-line treatment considered support during the decision-making process to be a high priority, trust in physicians seemed to be highly important in people with MS receiving second-line treatment. Patients focusing on physician recommendations at this stage of their disease might cope more effectively with the threat caused by the disease or by potential adverse effects.25 However, data indicate that natalizumab-treated patients differ in their risk perception and are willing to take higher risks than their physicians.26 This result is supported by the work of Kremer and colleagues27 showing that physicians, nurses, and people with MS agree with the relative importance of factors related to medication, except that patients rate safety significantly less important.

Moreover, in the present study people with MS with second-line treatment especially acknowledged the support of MS nurses as well as social networks. Therefore, the interaction of trust and autonomy in people with MS receiving second-line treatment requires further attention. In people with MS receiving first-line treatment, factors related to social interactions, such as perceived responsibility for others, were more often reported. It has been demonstrated previously that social support plays a major role in the treatment process of MS.28 However, the ability of the family, close relatives, or friends to provide such support largely depends on available resources. Thus, structural characteristics of the social environment have to be considered in the treatment process.

Differences in frequencies of cited elements indicated distinct profiles between the two groups. This supported the initial hypothesis that different categories have to be considered in assessing adherence of putative responders to treatment or at least historical nonresponders. In line with Bischoff and colleagues,20 the main reasons for nonadherence in people with MS receiving first-line treatment were burdensome adverse effects and lack of belief in medication effectiveness, whereas in the present study, people with MS receiving second-line treatment were more afraid of disease-related progression than of adverse effects. Being confronted with an active disease may outweigh the costs. Most people with MS receiving second-line treatment believed in substantial activity of their disease, and the main reason for nonadherence or discontinuation was a perceived lack of effectiveness. The belief in a sense of control through medication seemed to be more pronounced in first-line–treated people with MS. This observation points toward an important dilemma, ie, when patients hope that a new medication is more effective when experiencing breakthrough of the disease on first-line treatment while on the other hand their sense of control through medication might be lower. This might lead to nonadherence when disease activity persists.

Regarding limitations, this analysis did not study adherence to immunotherapies in general and was restricted to a comparison of two predefined groups. We chose participants who had changed treatment in the past to ensure their ability to compare different treatment experiences and, therefore, ensure enhanced reflection on treatment adherence and nonadherence. In the first-line treatment group we focused on people with oral treatments who had experiences with injectable medications in the past. Therefore, generalizability for first- and second-line–treated patients in general is limited because no persons with experience with only one drug were included. In addition, eight of 12 participants with second-line treatment received infusion-based treatments, which depend on regular encounters in MS centers. Intentional nonadherence is, therefore, rather unlikely. However, because this work intended to investigate an informative sample on a broad spectrum of putatively relevant aspects of adherence, we believe the approach to be justified. Frequency counting of statements to weigh categories might be biased depending on interviewers’ attitudes toward following up certain aspects in the interview. However, in an area with a multitude of aspects of adherence, this might help interviewers concentrate on key domains. That most of the participants were recruited from a university outpatient clinic further limits external validity. Finally, because the approach started from a theory-based set of categories, we might have missed categories not fitting the concept. However, although the interview guideline was theory-driven, the stepwise adaption of the categories was data-driven and led to 21 final categories. In addition, the approach of counting elements in qualitative research is a matter of debate and might induce bias because interviewer behavior may substantially influence how much a predefined category is discussed. However, if many dimensions are potentially relevant, as in the area of adherence, such an approach might help to disentangle most relevant factors and differences between the two groups.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate different patterns underlying adherence behavior in people with MS receiving either first- or second-line treatment undergoing immunotherapy. Findings emphasize that motivational factors for adherence behavior are diverse and not limited to drug-related factors such as adverse effects. Instead, psychological factors such as illness beliefs or factors concerning treatment decision making, as well as structural factors of the health care system, eg, implementation support, and the social environment, need to be considered when targeting improvement of adherence behavior in people with MS.

PRACTICE POINTS

Low treatment adherence in people with MS is associated not only with relapse or disease progression but also with an increase in subsequent health care costs.

The present research demonstrates that different factors are associated with treatment adherence in individuals receiving first-line treatment versus second-line treatment. Thus, the different patient groups require different approaches to overcome nonadherence.

Acknowledgments

The work of Theresa Rholoff and Kathrin Liethmann and their support during data collection and structuring are gratefully acknowledged.

References

Belbasis L, Bellou V, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP, Tzoulaki I. Environmental risk factors and multiple sclerosis: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Neurol. 2015; 14: 263– 273.

Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG. Disease modifying therapies for relapsing multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2016; 354: i3518.

Kobelt G, Thompson A, Berg J, Gannedahl M, Eriksson J, MSCOI Study Group, European Multiple Sclerosis Platform. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler. 2017; 23: 1123– 1136.

World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for Action . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

Menzin J, Caon C, Nichols C, White LA, Friedman M, Pill MW. Narrative review of the literature on adherence to disease-modifying therapies among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013; 19: S24– S40.

Gerber B, Cowling T, Chen G, Yeung M, Duquette P, Haddad P. The impact of treatment adherence on clinical and economic outcomes in multiple sclerosis: real world evidence from Alberta, Canada. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017; 18: 218– 224.

Burks J, Marshall TS, Ye X. Adherence to disease-modifying therapies and its impact on relapse, health resource utilization, and costs among patients with multiple sclerosis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2017; 9: 251– 260.

Haase R, Kullmann JS, Ziemssen T. Therapy satisfaction and adherence in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: the THEPA-MS survey. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016; 9: 250– 263.

Thach A, Chimah C, Makhinova T, Brown C. A review of methodologies used to assess adherence to disease modifying therapies among patients with multiple sclerosis. Value in Health. 2015; 18: 285.

Hansen K, Schüssel K, Kieble M, . Adherence to disease modifying drugs among patients with multiple sclerosis in Germany: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0133279.

Lizán L, Comellas M, Paz S, Poveda JL, Meletiche DM, Polanco C. Treatment adherence and other patient-reported outcomes as cost determinants in multiple sclerosis: a review of the literature. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014; 8: 1653– 1664.

White S, Clyne W, Mshelia C. An educational framework for managing and supporting medication adherence in Europe. Pharm Educ. 2013; 13: 118– 120.

Zwibel H, Pardo G, Smith S, Denney D, Oleen-Burkey M. A multicenter study of the predictors of adherence to self-injected glatiramer acetate for treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2011; 258: 402– 411.

McKay KA, Tremlett H, Patten SB, . CIHR Team in the Epidemiology and Impact of Comorbidity on Multiple Sclerosis (ECoMS). Determinants of non-adherence to disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: a cross-Canada prospective study. Mult Scler. 2017; 23: 588– 596.

Giovannoni G, Southam E, Waubant E. Systematic review of disease-modifying therapies to assess unmet needs in multiple sclerosis: tolerability and adherence. Mult Scler. 2012; 18: 932– 946.

Köpke S, Solari A, Khan F, Heesen C, Giordano A. Information provision for people with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 10: CD008757.

Halpern R, Agarwal S, Borton L, Oneacre K, Lopez-Bresnahan MV. Adherence and persistence among multiple sclerosis patients after one immunomodulatory treatment failure: retrospective claims analysis. Adv Ther. 2011; 28: 761– 765.

Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods . 4th ed. Sage Publications: 2015.

Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/39517. 2014. Accessed May 2018.

Bischoff C, Schreiber H, Bergmann A. Background information on multiple sclerosis patients stopping ongoing immunomodulatory treatment: a multicenter study in a community-based environment. J Neurol. 2012; 259: 2347– 2353.

Twork S, Nippert I, Scherer P, Haas J, Pöhlau D, Kugler J. Immunomodulating drugs in multiple sclerosis: compliance, satisfaction and adverse effects evaluation in a German multiple sclerosis population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007; 23: 1209– 1215.

Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R, . The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2011; 18: 69– 77.

Kasper J, Köpke S, Mühlhauser I, Nübling M, Heesen C. Informed shared decision making about immunotreatment for patients with multiple sclerosis (ISDIMS): a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Neurol. 2008; 15: 1345– 1352.

Cofield SS, Thomas N, Tyry T, Fox RJ, Salter A. Shared decision making and autonomy among US participants with multiple sclerosis in the NARCOMS Registry. Int J MS Care. 2017; 19: 303– 312.

Tur C. Fatigue management in multiple sclerosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016; 18: 26.

Kraemer J, Kleiter I, Meuth SG, . Risk-benefit assessment of natalizumab therapy in multiple sclerosis patients and their treating physicians. Mult Scler. 2017; 23: 1014– 1015.

Kremer IE, Evers SM, Jongen PJ, Hiligsmann M. Comparison of preferences of healthcare professionals and MS patients for attributes of disease-modifying drugs: a best-worst scaling. Health Expectations. 2018; 21: 171– 180.

Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM, Gliottoni RC. Physical activity and quality of life in multiple sclerosis: intermediary roles of disability, fatigue, mood, pain, self-efficacy and social support. Psychol Health Med. 2009; 14: 111– 124.