Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Coping with Multiple Sclerosis Scale

Author(s):

Background: The Coping with Multiple Sclerosis Scale (CMSS) was developed to assess coping strategies specific to multiple sclerosis (MS). Despite its wide application in MS research, psychometric support for the CMSS remains limited to the initial factor analytic investigation by Pakenham in 2001.

Methods: The current investigation assessed the factor structure and construct validity of the CMSS. Participants with MS (N = 453) completed the CMSS, as well as measures of disability related to MS (Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale), quality of life (World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Scale), and anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale).

Results: The original factor structure reported by Pakenham was a poor fit to the data. An alternate seven-factor structure was identified using exploratory factor analysis. Although there were some similarities with the existing CMSS subscales, differences in factor content and item loadings were found. Relationships between the revised CMSS subscales and additional measures were assessed, and the findings were consistent with previous research.

Conclusions: Refinement of the CMSS is suggested, especially for subscales related to acceptance and avoidance strategies. Until further research is conducted on the revised CMSS, it is recommended that the original CMSS continue to be administered. Clinicians and researchers should be mindful of lack of support for the acceptance and avoidance subscales and should seek additional scales to assess these areas.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive health condition that affects physical, cognitive, and emotional aspects of a person's life.1 Emotional and psychological adjustment to MS can be especially difficult because of the diversity of symptoms, absence of a cure, limited availability of medical treatment, and uncertainty about the future effects of the disease on one's physical abilities.2–4 Psychological outcomes for individuals with MS have been found to be more closely related to controllable factors (ie, cognitive and behavioral factors) than to the unpredictable physical effects of the disease.5 As such, attention has been given to the assessment of strategies for coping with MS.

Pakenham6 developed the Coping with Multiple Sclerosis Scale (CMSS) to assess various strategies used to cope with MS illness–related stressors. Items were generated from semistructured interviews that asked participants with MS (N = 135; mean ± SD age, 48.66 ± 11.32 years; 78% female) about their coping strategies. Three health professionals reviewed the draft items for their relevance. Additional participants were recruited to complete a draft self-report questionnaire. Responses to the draft items (N = 414 participants; mean ± SD age, 48.06 ± 11.62 years; 76% female) were analyzed using a combination of principal components and principal axis factor analyses, which suggested seven subscales comprising 29 items assessing problem-solving, acceptance, avoidance, energy conservation, emotional release, physical assistance, and personal health control. Criterion validity of the CMSS was supported by its moderate correlations with subscales from the Ways of Coping Checklist7 as well as adjustment outcomes. The internal consistency of the CMSS subscales ranged from low to acceptable (Cronbach α = 0.56–0.70).6 The test-retest reliabilities of the CMSS over a 3-month interval ranged from 0.63 to 0.75, demonstrating high stability over the short term.8

Since its development, the CMSS has been used in a variety of different capacities. The CMSS subscales have been used as predictor variables in investigations aimed at identifying coping strategies associated with positive adjustment outcomes (eg, acceptance coping5 8) and to establish convergent validity for a newly developed acceptance coping measure.9 The CMSS has also been used as an outcome measure for evaluating the efficacy of a fatigue management group intervention for individuals with MS.10

Despite its wide application in MS research, psychometric support for the CMSS remains limited to the initial factor analytic investigation.6 Additional investigation of the psychometric properties of the CMSS is warranted. The current investigation used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to determine whether the factor model for the CMSS reported by Pakenham6 could be replicated. As noted later herein, when the factor structure and item loadings could not be confirmed, we reconsidered the factor structure and item loadings of the CMSS using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Because previous research has found differential associations of CMSS subscales and adjustment outcomes,6 8 criterion validity for the alternate factor structure for the CMSS was explored by assessing relationships between revised CMSS subscales and measures assessing disability related to MS, quality of life, and anxiety and depression.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited with the cooperation of various organizations, such as chapters of the MS Society of Canada and participating MS clinics in Canada; via online advertisements on MS-related websites; and through targeted advertisements on the social networking website Facebook. Using these methods, 730 people consented to participate in the research and began completion of background questions and measures via either an Internet (n = 683) or a paper-based (n = 47) survey. Two hundred seventy-seven cases were deleted from the data set: 192 because they were missing more than 20% of responses on three or more measures; 52 because they did not self-report a confirmed diagnosis of MS; and 33 because there was a duplicate IP address with identical birth date, sex, and province. The remaining 453 participants were self-selected adults (≥18 years old) who self-reported a confirmed diagnosis of MS.

These 453 participants ranged in age from 20 to 75 years, with a mean ± SD age of 43.69 ± 10.37 years. Most participants were white (n = 429, 94.7%), female (n = 365, 80.6%), married or in common law relationships (n = 264, 58.3%), and lived with their spouse exclusively (n = 173, 38.2%) or with their spouse and additional family members (n = 149, 32.9%). More than half of the participants had a college or technical certificate or a university degree (n = 235, 51.9%). Although many participants were working (part-time or full-time; n = 171, 37.7%), an equivalent number reported being unemployed due to MS (n = 181, 40.0%). More than a quarter of the participants were from Ontario (n = 127, 28.0%), and 41.7% of participants were from the prairie provinces (ie, Alberta, n = 92; Saskatchewan, n = 81; and Manitoba, n = 16).

At the time of survey completion, the mean ± SD number of years after MS diagnosis was 9.43 ± 8.39 years (range, 1–47 years). The mean ± SD time since the first appearance of symptoms was 15.06 ± 11.29 years (range, 1–60 years). A slight majority of the participants reported having relapsing-remitting MS (n = 273, 60.3%). Seventy participants (15.5%) had secondary progressive MS, 40 (8.8%) had primary progressive MS, 15 (3.3%) had progressive relapsing MS, 15 (3.3%) had benign MS, and 40 (8.8%) did not know their type of MS. Approximately half of the participants reported currently taking a disease-modifying therapy for MS (n = 232, 51.2%). Ethical approval was received from the research ethics boards of the University of Regina and the University of Saskatchewan.

Measures

Coping with Multiple Sclerosis Scale

The CMSS6 is presented in three parts. First, participants describe their main MS-related problem experienced in the past month. Second, participants rate how stressful the problem has been in the past month on a 7-point scale (from 1 = not at all stressful to 7 = extremely stressful). Third, participants respond to 29 questions assessing strategies for coping with MS-related problems using a 5-point scale (0 = does not apply/never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = very often). Subscales include problem-solving (five items; eg, “I focus on the here and now”), acceptance (five items; eg, “I accept the fact that it happened”), avoidance (four items; eg, “I keep pushing myself to get things done”), energy conservation (three items; eg, “I have a rest”), emotional release (three items; eg, “I let my feelings out”), physical assistance (five items; eg, “I ask for physical assistance”), and personal health control (four items; eg, “I seek alternative therapies such as . . .”).

29-Item Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale

The 29-item Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29)11 assesses the physical (20 items) and psychological (9 items) impact of MS. Using a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), participants rate the impact MS has had on various aspects of their day-to-day life during the past 2 weeks. Scores are summed on each factor and transformed to a 0 to 100 scale, with higher scores indicating greater physical and psychological difficulties related to MS. The MSIS-29 has demonstrated good internal consistency and convergent validity with other measures of health status.11 12

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)13 is a 14-item self-report instrument designed to assess anxiety (seven items) and depression (seven items) in populations with medical illnesses. Items were created to minimize illness-related content and are rated for agreement on a scale from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater agreement. Scores are summed for a total score on each scale ranging from 0 to 21. Scores of 8 or greater suggest clinical depression or anxiety.14 15 The HADS has been used extensively with individuals with varying chronic illnesses, including people with MS.16 17 The HADS has demonstrated good concurrent validity with other measures of depression and anxiety.14

World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Scale

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Scale (WHOQOL-BREF)18 19 is a 26-item short version of the WHOQOL-10020 and is used to assess quality of life domains, including physical (seven items), psychological (six items), social (three items), and environmental (eight items). Items are responded to on a 5-point Likert scale with descriptive endpoints differing for groups of questions (eg, from very dissatisfied to very satisfied or from not at all to completely). Two additional items query the respondents' perceptions about their overall quality of life and their overall health. The WHOQOL-BREF has demonstrated good internal consistency for the physical health, psychological, and environment scales but lower values for the social relationships scale, which is not unexpected given the small number of items for this subscale. The measure has demonstrated discriminant validity by its ability to differentiate between respondents who were sick versus well.20 We computed only the WHOQOL-BREF subscale (not domain) scores according to the manual, reversing items 3 and 4.

Data Analytic Plan

Skewness and kurtosis statistics were calculated for the study variables. Skewness values greater than 3 and kurtosis values greater than 10 were indicative of non-normality.21 Scores on all measures were examined for univariate outliers using the recommendation of standardized scores in excess of ±3.29 (P < .001, 2-tailed test), and outliers were replaced with scores that were 1 unit different (larger or smaller) than the next most extreme score.22 Confirmatory factor analysis was used to determine whether the seven-factor solution proposed by Pakenham6 for the CMSS could be replicated. Maximum likelihood estimation of the variance-covariance matrix was conducted using Amos version 18.0 statistical software (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL). As recommended by Hu and Bentler23 and Browne and Cudeck,24 multiple fit indices were evaluated to determine which factor structure was the best fit to the observed data. The following fit indices were examined: 1) χ2 (values should not be statistically significant, although that is almost always so given the sample size); 2) χ2 to degrees of freedom (:df) ratio (values should be <3.021); 3) comparative fit index (values should be >0.95 or >0.90 [more liberal criteria25]); 4) goodness-of-fit index (values should be >0.95 or >0.90 [more liberal criteria25]); 5) normed fit index (values should be >0.95 or >0.90 [more liberal criteria25]); 6) root mean residual square (values should be <0.05 or <0.08 [more liberal criteria21]); and 7) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; values should be <0.05 or <0.08 [more liberal criteria25]). As noted later herein, when the factor structure could not be confirmed, EFA was used to explore alternate solutions using principal axis factoring with promax (oblique) rotation as recommended by Costello and Osborne.26 Finally, the subscales were correlated with measures of adjustment.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

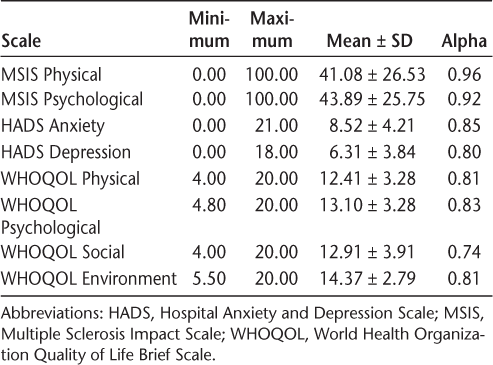

Scores of skewness and kurtosis from all measures fell within the reference range. Univariate outliers were identified and replaced with scores that were 1 unit different (larger or smaller) than the next most extreme score.22 The number of univariate outliers modified in this manner varied from one score to eight scores depending on the measure. The Cronbach alpha was calculated to assess the internal consistency of measures. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics for all the measures, excluding the CMSS.

Descriptive statistics for the study measures

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The CFA of the 29 items of the CMSS assigned to factors according to Pakenham6 resulted in a poor model fit: χ2 356 = 1099.534, P < .0001, χ2:df = 3.089, comparative fit index = 0.760, goodness-of-fit index = 0.855, normed fit index = 0.687, root mean residual square = 0.097, RMSEA = 0.068 (90% confidence interval = 0.063–0.073). Thus, only for the liberal criteria for RMSEA was the model acceptable. All the items loaded on their respective factors (P < .001) except for item 26 (“I control my emotions”). Four other items (items 14, 32, 34, and 36) accounted for negligible amounts (r 2 < 0.10) of the variance in their respective factors. The Cronbach alpha for the total scale was a respectable α = 0.79, but three items had quite small and negative-corrected item total correlations (ranging from −0.019 to −0.034). The mean interitem correlation for the 29 items was r = 0.116, with the largest correlation between any two items being r = 0.596.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

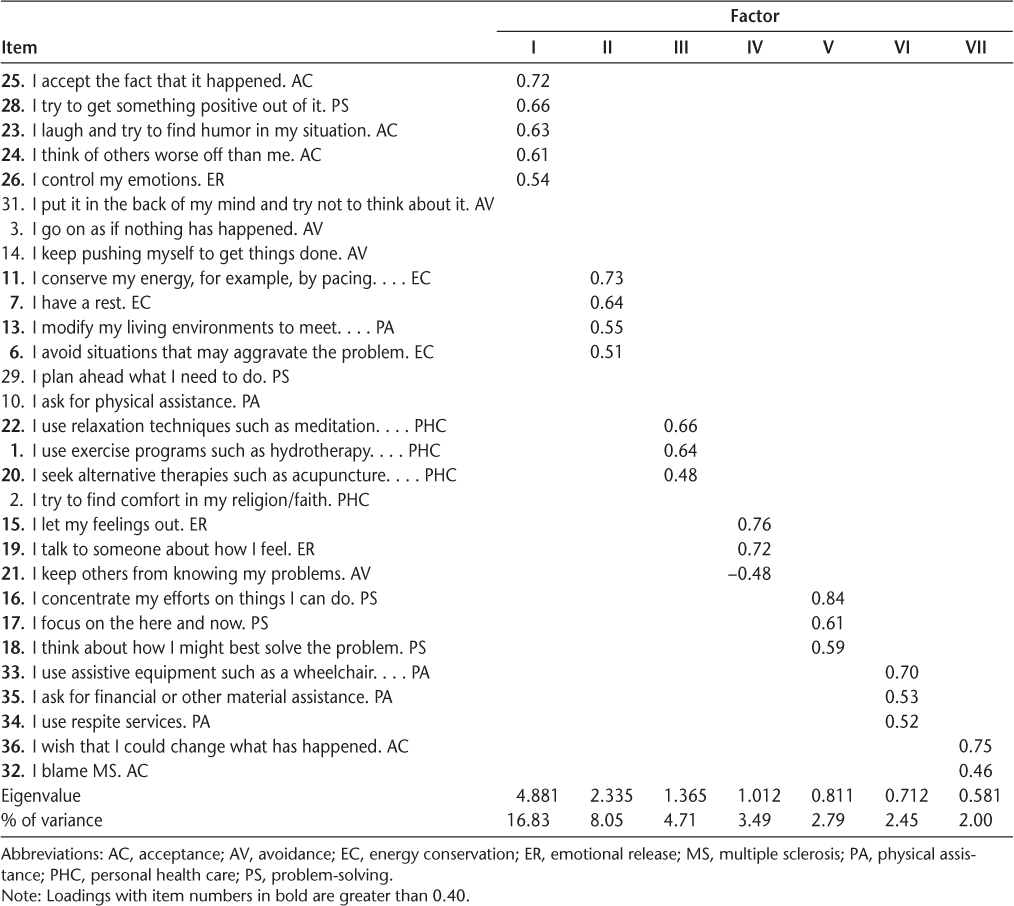

Having failed to produce a well-fitting CFA model for the CMSS that replicated the findings of Pakenham,6 we reverted to EFA. We did the EFA using principal axis factoring with promax (oblique) rotation.26 Eigenvalues ranged from 5.401 to 1.100. An eighth factor had an eigenvalue of 1.067. Nonetheless, we forced a seven-factor solution, although other factor solutions (eg, six and eight) were also considered. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.821, and the Barlett test of sphericity was significant (χ2 406 = 3428.697, P < .001). The seven factors after extraction accounted for 40.34% of the variance, with the first factor accounting for 16.83% of the variance, the second factor for 8.05%, the third factor for 4.71%, and the other factors for 4% or less. The cutoff value for an item loading on a factor was set at 0.40. There were no items that cross-loaded based on the 0.40 cutoff point.

Our EFA solution and how it compares with the solution presented by Pakenham6 is presented in Table 2. Working backward, some factors from Pakenham were retained, albeit with a smaller number of items: factor VII is Pakenham's acceptance factor, factor VI is his physical assistance factor, factor V is his problem-solving factor, and factor III is his personal health care factor. Factor IV retained its identity as Pakenham's emotional release factor, albeit with the addition of a negative loading item (item 21: “I keep others from knowing my problems”). The opposite of emotional release would be keeping others from knowing one's problems.

Exploratory factor analysis of the Coping with Multiple Sclerosis Scale

Factors I and II were not as easily interpreted. The highest loading items on factor II relate to energy conservation (ie, item 11: “I conserve my energy”; item 7: “I have a rest”; and item 6: “I avoid situations that may aggravate the problem”). In the midst of those items is item 13 (“I modify my living environments to meet my needs”). One could interpret that original physical assistance item as having modified one's environment to make life easier and, thus, conserve energy.

The highest loading item on factor I was item 25 (“I accept the fact that it happened”) (originally an acceptance item). Similarly, the third item (item 23: “I laugh and try to find humor in my situation”) and the fourth item (item 24: “I think of others worse off than me”) were also originally acceptance items. Conversely, the second highest loading item on factor I (item 28: “I try to get something positive out of it”) was a problem-solving item, and the fifth highest loading item on this factor was from the emotional release factor (item 26: “I control my emotions”). One could interpret both of those items as having elements of acceptance, so this factor might best be interpreted as acceptance. What is lost in the factor analysis is Pakenham's original avoidance factor; what is gained is not one but two acceptance factors. Furthermore, six items from Pakenham's original measure (items 2, 3, 10, 14, 29, and 31) did not load highly on any of the seven factors.

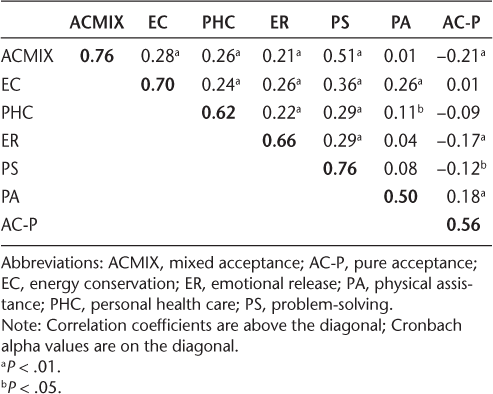

The correlations between the subscales from the revised 23-item CMSS (with the ≥0.40 cutoff point for items) are presented above the diagonal in Table 3. Note the substantial and negative correlation between the two acceptance subscales, mixed acceptance and pure acceptance. On the diagonal in Table 3, the internal consistency for each of the reconstituted factors of the revised 23-item CMSS is presented. Internal consistency ranged from a low of α = 0.50 for physical assistance to a high of α = 0.76 for mixed acceptance and problem-solving.

Correlations between subscales of the 23-item Coping with Multiple Sclerosis Scale

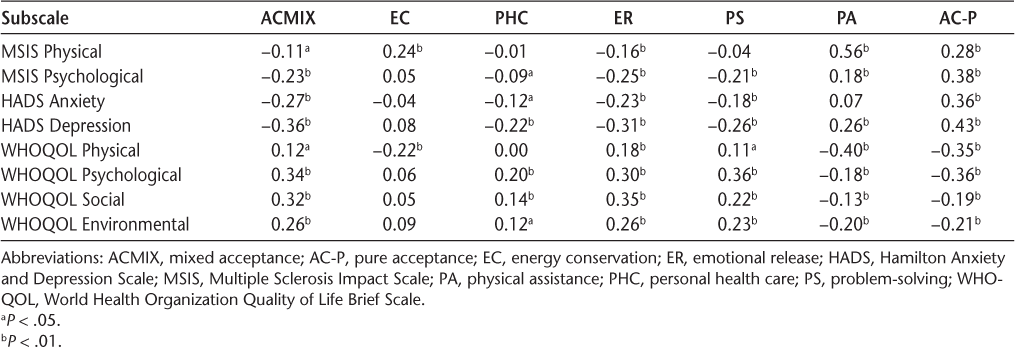

Correlations with Other Measures

Table 4 presents the correlations between the factors of the revised CMSS and the measures of adjustment. The mixed acceptance and pure acceptance factors were mirror images of each other, correlating with all measures of adjustment except for the mixed acceptance factor not correlating with MSIS physical. The emotional release and problem-solving factors were positively associated with the WHOQOL-BREF subscales and were negatively associated with the HADS and MSIS subscales. The physical assistance factor was positively associated with the MSIS subscales and the HADS Depression subscale and negatively associated with the WHOQOL-BREF subscales. The personal health care factor was negatively related to the HADS Depression subscale and positively related to the WHOQOL-BREF Psychological and Social subscales. Finally, the energy conservation factor was related to the MSIS Physical subscale positively and the WHOQOL-BREF Physical subscale negatively.

Correlations between subscales of the 23-item Coping with Multiple Sclerosis Scale and measures of adjustment to multiple sclerosis

Discussion

The primary purpose of this investigation was to assess the factor structure of the CMSS in a sample of individuals with MS. The seven-factor, 29-item solution proposed by Pakenham6 could not be replicated using CFA, as evidenced by poor model fit and several items that loaded negligibly or not at all on their respective factors. The EFAs partially supported an alternate seven-factor solution comprising 23 items. Subscale internal consistencies were within the range of values reported by Pakenham.6 Differences in factor content and item loadings between the original and the revised 23-item CMSS solution are discussed because they highlight the need for further refinement of the CMSS subscales.

Two acceptance factors emerged from the EFAs. The first acceptance factor consisted primarily of items from Pakenham's6 original acceptance factor. A single item from each of Pakenham's problem-solving and emotional release factors also loaded saliently on the first acceptance factor (“I try to get something positive out of it” and “I control my emotions,” respectively). Both items were interpreted as having elements of acceptance and were deemed appropriate additions to the acceptance factor. Nonetheless, ambiguity of item content could suggest the need for refinement or reconstruction of items. The second acceptance factor had only two items, both reverse worded, also from Pakenham's original acceptance factor (“I wish that I could change what has happened” and “I blame MS”). Existing evidence consistently demonstrates that scales with reverse-worded items are not represented well unidimensionally,27 28 possibly due to careless responding29 or inattention or confusion.30 Because abandonment of reverse-worded items is consistently recommended,31–33 we attempted to remove Pakenham's reverse-worded items from the analyses; however, results were uninterpretable. It is possible that reconstruction of the reverse-worded acceptance items may allow for a unidimensional scale of acceptance to reemerge. Nonetheless, further refinement of the acceptance scale of the CMSS is warranted.

The remaining five factors closely resembled Pakenham's6 original factors, with some minor differences: 1) the physical assistance, problem-solving, and personal health care factors had reduced numbers of items; 2) the emotional release factor gained a negative-loading item (“I keep others from knowing my problems”) (originally from Pakenham's avoidance factor), the content of which was interpreted as having negative-worded representation of emotional release; and 3) one retained factor (energy conservation) had an additional item (“I modify my living environments to meet . . .”) (from Pakenham's physical assistance factor), which was interpreted as a strategy to conserve energy. Future psychometric evaluation of the CMSS should include assessment of the stability of the items that have changed factors.

Another difference from the original CMSS factor structure6 was the loss of the original avoidance factor. Most of the avoidance items loaded less than 0.40 on the first acceptance factor and subsequently were removed from the solution. Avoidance is a common form of coping for patients with MS34 and is predictive of poor adjustment.8 It is unclear why the avoidance items did not load saliently in the present investigation. One possibility is that avoidance might be better conceptualized as lack of engagement in approach-based coping strategies than as a factor in itself. For example, patients with MS who regularly use avoidance strategies are less likely to use task-oriented strategies.34 Furthermore, quality of life outcomes are associated positively with task-oriented strategies and negatively with avoidance coping.34 Another possibility is that Pakenham's avoidance items did not effectively capture avoidant content. For example, items such as “I keep pushing myself to get things done” and “I go on as though nothing has happened” could potentially reflect denial rather than avoidance, which is one of the least used coping mechanisms among patients with MS.35 The avoidance items may also be focused too heavily on behavioral avoidance, whereas other forms of avoidance might be more relevant (eg, emotional avoidance). Such possibilities are speculative; nonetheless, future refinement of the avoidance construct in the CMSS is necessary.

It is important to consider whether differences in sample features might have contributed to differences in factor structure across studies. However, this sample shared many similarities with Pakenham's6 sample and exhibited few differences. In the present sample, the mean age was 44 years, 80.6% were female, 51.9% had completed at least some postsecondary education, and 40% reported being unemployed due to MS. The sample used to validate the CMSS6 was similar: the mean age was 48 years, the sample was 76% female, 41% had completed at least some postsecondary education, 30% were receiving a disability benefit, and an additional 14% were unemployed. The present sample reported that 15.06 years had elapsed since their first MS symptom and that 9.43 years had passed since diagnosis; Pakenham's sample reported 14.38 and 9.2 years, respectively. In terms of disease course, both samples had similar numbers of participants reporting relapsing-remitting (66% and 62%) and progressive (27.6% and 38%) forms of MS. Unlike Pakenham's sample, the present sample also had a small percentage of individuals who reported a benign MS disease course (3.3%) or did not know their disease course (8.8%). Given the similarity of this sample to Pakenham's sample, the lack of generalizability of the CMSS subscales is quite surprising.

The present investigation evaluated the validity of the revised CMSS subscales by assessing relationships of the subscales with outcome measures of MS-related disability, quality of life, anxiety, and depression. These findings were consistent with existing research.8 In general, acceptance, personal health care, emotional release, and problem-solving correlated positively with positive outcomes and negatively with negative outcomes. The personal assistance and reverse-worded acceptance factors demonstrated the exact opposite associations as the other subscales, correlating positively with negative outcomes and negatively with positive outcomes. The energy conservation factor was associated with MS-related physical disability only. Although energy conservation was unrelated to the other outcome measures, prospective research has found energy conservation to be predictive of increased benefit finding (personal growth) and positive affect at 3 months' follow-up.8

Although the present findings did not fully support the factor structure reported by Pakenham,6 it is important to emphasize that there were many similarities in the factor structures. In terms of overall content theme, six of the seven subscales aligned with those reported by Pakenham: acceptance, physical assistance, problem-solving, personal health care, emotional release, and energy conservation factors. Such findings should strengthen our confidence that these are distinct coping strategies used by individuals with MS that can be measured using the CMSS. This cannot be said for Pakenham's avoidance subscale, however. To be clear, substantial evidence indicates that avoidance is a distinct MS coping strategy with important consequences for adjustment.8 34 That being said, the avoidance items outlined in the original CMSS did not capture avoidance coping in this sample. We maintain that all the CMSS subscales require further refinement, but greatest emphasis should be given to creating and validating items that measure MS-related avoidance coping. At this time, given that further research on the CMSS subscales is needed, we recommend that clinicians continue to administer the full CMSS while maintaining an awareness that supplementary interview information and measures may be necessary to assess avoidance coping and validate the results of the other subscales.

This study has limitations that highlight important avenues for future research. First, participants in this study were self-selected individuals who self-identified as having MS. Replication using a sample of individuals with verified MS diagnoses would be helpful, although past research does suggest that there is a high degree of correspondence between self-reported diagnosis of MS and medically recorded or physician-reported diagnosis.36

Not included in these analyses were responses from a significant number of participants who had missing data. Individuals who volunteer to participate in research related to MS coping (and who follow through to completion) may be inherently less avoidant and may use more positive, active coping methods. Future studies examining the psychometric properties of the CMSS may capture an even wider range of responses by investigating the coping methods of patients with MS across specific sites (eg, MS management groups and general practices). Second, reflective of the composition of people diagnosed as having MS, the sample was predominantly female. Sex differences have been identified in terms of coping strategies used by patients with MS.37 Future investigations should test for differential item functioning of the CMSS to assess for potential sex-based biases. Third, there was substantial diversity in the length of time individuals reported having symptoms of MS. Examination of psychometric properties in different stages or types of MS may reveal underlying differences in how coping with MS changes across the disease course. And fourth, although the sample of 453 individuals with MS is substantial, it was insufficient to create a verification sample, so the results should be considered preliminary.

The present study assessed the factor structure of the CMSS in a sample of individuals with MS. The original solution6 could not be replicated using CFA. An alternate factor structure was partially supported by EFA. Refinement of the CMSS subscales is necessary, especially for the acceptance and avoidance scales. Psychometric properties of the CMSS may improve with refinement of ambiguous and reverse-worded items. In the meantime, it is recommended that the full CMSS be administered; however, clinicians and researchers would benefit from awareness of potential issues associated with the measure. Coping strategies are consistently emerging as one of the most powerful predictors of positive and negative adjustment outcomes.38 Nonetheless, scientific discovery is only as sound as the measures used to assess phenomena. As such, additional investigations into the psychometric properties of the CMSS are needed.

PracticePoints

The present study assessed the factor structure of the Coping with Multiple Sclerosis Scale (CMSS) in a sample of individuals with MS. The original solution could not be replicated using confirmatory factor analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis suggested that the CMSS likely requires refinement in terms of the scoring of the acceptance and avoidance strategies subscales.

It is recommended that the full CMSS be administered; however, clinicians and researchers would benefit from awareness of problems with the acceptance and avoidance subscales.

References

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–1517.

Crayton H, Heyman RA, Rossman HS. A multimodal approach to managing the symptoms of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63(suppl 5):S12–S18.

Lublin FD. Clinical features and diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2005;23:1–15.

Myhr KM. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;117(suppl 188):12–21.

Chalk HM. Mind over matter: cognitive-behavioral determinants of emotional distress in multiple sclerosis patients. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:556–566.

Pakenham KI. Coping with multiple sclerosis: development of a measure. Psychol Health Med. 2001;6:411–428.

Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The relationship between coping and emotion: implications for theory and research. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26:309–317.

Pakenham KI. Investigation of the coping antecedents to positive outcomes and distress in multiple sclerosis (MS). Psychol Health. 2006;21:633–649.

Pakenham KI, Fleming M. Relations between acceptance of multiple sclerosis and positive and negative adjustments. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1292–1309.

Sutherland JK, Cowan PA. Using special interest sessions to design and implement a fatigue management group for people with multiple sclerosis. Psychiatr Bull. 2005;29:388–391.

Hobart J, Lamping D, Fitzpatrick R, Riazi A, Thompson A. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): a new patient-based outcome measure. Brain. 2011;124:962–973.

Riazi A, Hobart JC, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, Thompson AJ. Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29): reliability and validity in hospital based samples. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:701–704.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370.

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77.

Honarmand K, Feinstein A. Validation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for use with multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2009;15:1518–1524.

Feinstein A, O'Connor P, Gray T, Feinstein K. The effects of anxiety on psychiatric morbidity in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 1999;5:323–326.

Kehler MD, Hadjistavropoulos HD. Is health anxiety a significant problem for individuals with multiple sclerosis? J Behav Med. 2009;32:150–161.

Skevington SM, Lofty M, O'Connell KA. The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial: a report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310.

WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–558.

WHOQOL Group. Development of the WHOQOL: rationale and current status. Int J Mental Health. 1994;23:24–56.

Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th ed. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Pearson; 2007.

Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6:1–55.

Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, eds. Testing Structural Equation Models. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1993:36–162.

Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010.

Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10. http://pareonline.net/pdf/v10n7.pdf.

Rodebaugh TL, Woods CM, Thissen DM, Heimberg RG, Chambless DL, Rapee RM. More information from fewer questions: the factor structure and item properties of the original and brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Psychol Assess. 2004;16:169–181.

Woods CM, Rodebaugh TL. Factor structures of the original and brief Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE and BFNE) scales: correction to an erroneous footnote. Psychol Assess. 2005;17:385–386.

Schmitt N, Stults D. Factors defined by negatively keyed items: the result of careless respondents? Appl Psychol Measure. 1985;9:367–373.

van Sonderen E, Sanderman R, Coyne JC. Ineffectiveness of reverse wording of questionnaire items: let's learn from cows in the rain. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68967.

Barnette JJ. Effects of stem and Likert response option reversals on survey internal consistency: if you feel the need, there is a better alternative to using those negatively worded stems. Educ Psychol Measure. 2000;6:361–370.

Sliter KA, Zickar MJ. An IRT examination of the psychometric functioning of negatively worded personality items. Educ Psychol Measure. 2014;74:214–226.

Woods CM. Careless responding to reverse-worded items: implications for confirmatory factor analysis. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2006;28:186–191.

Goretti B, Portaccio E, Zipoli V, et al. Coping strategies, psychological variables and their relationship with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2009;30:15–20.

Lode K, Larsen JP, Bru E, Klevan G, Myhr KM, Nylan H. Patient information and coping styles in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:792–799.

Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Vollmer T. Validation of the NARCOMS registry: diagnosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:770–775.

McCabe MP, McKern S, McDonald E. Coping and psychological adjustment among people with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:355–361.

Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. A review of psychological correlates of adjustment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:141–153.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Regional Partnership Program; and the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, University of Regina.