Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Assessing Four Quality Indicators for Multiple Sclerosis Management Through Patient-Reported Data

Author(s):

Background: Although hundreds of quality indicators (QIs) have been developed for various chronic conditions, QIs specific to multiple sclerosis (MS) care have only recently been developed. We sought to examine the extent to which the self-reported care of individuals with MS meets four recently developed MS QIs related to treatment of depression, spasticity, and fatigue and timely initiation of disease-modifying agents (DMAs) for relapsing MS.

Methods: Using the Sonya Slifka Study data, we examined the proportion of the MS population meeting four QIs (based on patient-reported data) in a sample of individuals with MS in 2007–2009. For the three diagnoses, meeting the QI was defined as receiving appropriate medication or seeing a provider for treatment of the diagnosis; for timely initiation, it was defined as receiving a DMA within 3 months of a relapsing MS diagnosis. We also examined differences in characteristics between respondents who met the QI versus those who did not.

Results: Approximately two-thirds of people with MS in this sample, per the predefined criteria, met the QIs for treatment of depression, management of spasticity, and DMA initiation within 3 months of a relapsing diagnosis, and approximately one-fifth met the QI for management of fatigue. There were some significant differences in characteristics between respondents who met the QIs and those who did not.

Conclusions: This study examined a subset of MS QIs based on patient-reported data. Additional data sources are needed to fully assess compliance with MS QIs.

Hundreds of quality measures and quality indicators (QIs) have been developed for various chronic conditions to assess and track health-care quality.1 2 Quality of care is often measured in terms of processes or outcomes, and there has been a call for more patient-reported outcomes in health care. A key purpose of measuring quality of care is to measure the current level of quality provided, based on the current evidence, and to ultimately improve practice and positively affect patient outcomes. Although there has been much attention paid to quality measurement in some settings (eg, hospitals), specialties (eg, internal medicine), and certain conditions (eg, diabetes), there has been little focus on measuring quality in neurology and multiple sclerosis (MS), until recently.3 4 In particular, Cheng et al.4 published a comprehensive set of QIs of MS care that was developed using a consensus process with experts in the field. Although MS care, similar to other health-care delivery, has long been informed by established guidelines, these MS QIs represent the first step toward providing a systematic approach to measure quality, comparable with that done for other conditions. Measuring the quality of MS care presents an opportunity to systematically determine whether, in fact, evidence-based care is being provided to individuals with MS. There are several challenges to effectively measuring the often complex nature of health-care decisions and the care provided, yet the importance of attempting to measure quality remains. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has attempted to operationalize and report results from these newly developed MS QIs.

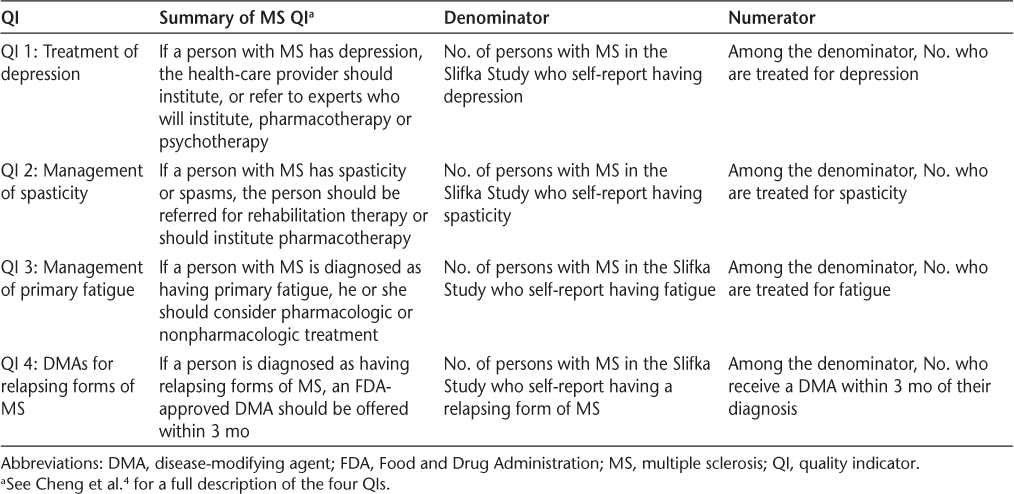

This study aims to expand our understanding of the extent to which the self-reported care of individuals with MS meets a subset of four MS QIs. Table 1 provides a summary of the four quality measures as well as a brief explanation of each measure's numerator and denominator. These concepts are discussed in greater detail herein.

Summary of the four QIs examined

Materials and Methods

For a sample of individuals with MS in 2007–2009, we examined the proportion who met four of the MS QIs developed by Cheng et al.4: three QIs focus on the management of MS symptoms—depression, spasticity, and fatigue—and one QI measures the initiation of a disease-modifying agent (DMA) in individuals with a relapsing MS diagnosis. These four QIs were selected because of their focus on medication management and the feasibility of measuring them with the available secondary data.

Data Source

For this study, we used the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study (Slifka Study). Since 2000, the Slifka Study has collected epidemiologic, clinical, and health services utilization and cost data by computer-assisted telephone interviews. A detailed description of the Slifka Study is provided elsewhere.5

Sample

The Slifka Study is a longitudinal study comprising two distinct cohorts. For this study, we used interviews with respondents from cohort 2, who were recruited in 2007 (n = 2478). The sample was constructed by drawing a probability sample from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society's mailing list (mailing list respondents), and then augmenting the sample by recruiting additional respondents who were recently diagnosed, African American or Hispanic race, or 18 to 24 years old (outreach respondents).

For each QI, we identified a “denominator” group (ie, the group with the diagnosis) and a “numerator” or “treated” group (ie, the group that met the QI). The analytic approaches for the three symptom management QIs were similar and are, therefore, described together. Because the analytic approach for the fourth QI on DMA use in relapsing MS diagnoses differed from that of the symptom management QIs, it is described separately.

Defining the Sample for the Symptom Management QIs (QIs 1–3)

To examine the QIs related to the management of depression, spasticity, and fatigue, we used the cohort 2 Slifka Study 2009 interview. This sample included 1527 individuals (1149 mailing list respondents and 378 outreach respondents). To construct the denominator group, we identified respondents who reported the symptom of interest (ie, depression, spasticity, or fatigue) or who reported the symptom of interest as the reason for a visit to a physician's office or medical facility (eg, emergency department) since their last interview (20 months on average). Thus, we categorized a respondent as having a “diagnosis” if he or she either reported currently experiencing the symptom or reported the symptom as the reason for health-care utilization.

Among the respondents assigned to the denominators for each of the three QIs, the treated group was defined as respondents who reported taking a medication. For the depression and spasticity QIs, respondents were also included in the treated group if they reported seeing a provider for their symptom. Unfortunately, we were unable to operationalize all aspects of the QIs because some data were unavailable; see the discussion of limitations later herein for further details. A licensed pharmacist (SS) compiled the list of medications to manage each of the symptoms based on commonly used medications for MS symptom management.6 The list of medications was reviewed for accuracy and completeness by a practicing MS specialist nurse. The list of medications used to manage each symptom is provided in Supplementary Table 1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org.

Defining the Sample for DMA Initiation Among Relapsing Forms of MS (QI 4)

We used the cohort 2 Slifka Study baseline interview (conducted in 2007–2008) to examine the QI related to initiation of a DMA in people with a relapsing MS diagnosis (ie, relapsing-remitting MS or progressive relapsing MS). This sample consisted of 2478 individuals (1848 mailing list respondents and 630 outreach respondents). Although this QI was first published in 2010, the American Academy of Neurology published guidelines for initiation of DMAs in patients with relapsing MS in 2002.7 The assumption was that adoption of the American Academy of Neurology guidelines could take up to a year to become common practice. As a result, we further restricted the sample of relapsing MS respondents to those who were diagnosed as having relapsing MS on January 1, 2003, or later. This resulted in 797 cohort 2 respondents with a relapsing MS diagnosis since 2003 (denominator group).

Among these respondents, we then identified the percentage who reported receiving any of the following DMAs within 3 months of their diagnosis: interferon beta-1a (Avonex; Biogen Idec, Cambridge, MA; and Rebif; EMD Serono, Inc, Rockland, MA), interferon beta-1b (Betaseron; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Montville, NJ), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, North Wales, PA), mitoxantrone (Novantrone; EMD Serono, Inc, Rockland, MA), and natalizumab (Tysabri; Biogen Idec Inc [Cambridge, MA] and Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc [South San Francisco, CA]). This indicates the percentage of respondents who met the QI (ie, the treated group).

Weighting

As described previously herein, the Slifka Study is a random sample of people with MS with oversampling of specific subgroups. Among the cohort 2 oversampled respondents, most were newly diagnosed; newly diagnosed patients composed 68.7% of the cohort 2 oversampled respondents at the baseline interview in 2007–2008 and a similar percentage in the 2009 interview. In addition, the newly diagnosed patients compose approximately 17% of all Slifka Study respondents for each of the two interviews. This proportion is greater than typically seen in the general US MS population. To represent the population of patients with MS in the United States, we applied poststratification8 to the Slifka Study sample. The poststratification weighting method is described in detail elsewhere.9

Analysis

For each QI, we report the percentage of the diagnosed MS population that met each of the QIs examined (ie, the percentage of the denominator group that was treated). We used the χ2 test for categorical variables and the t test for continuous variables to examine the differences in characteristics between respondents who met the QI versus those who did not. We used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) for data analysis. We report weighted results unless otherwise noted. This study was exempt from institutional review board review because we used secondary data.

Results

Sample Characteristics

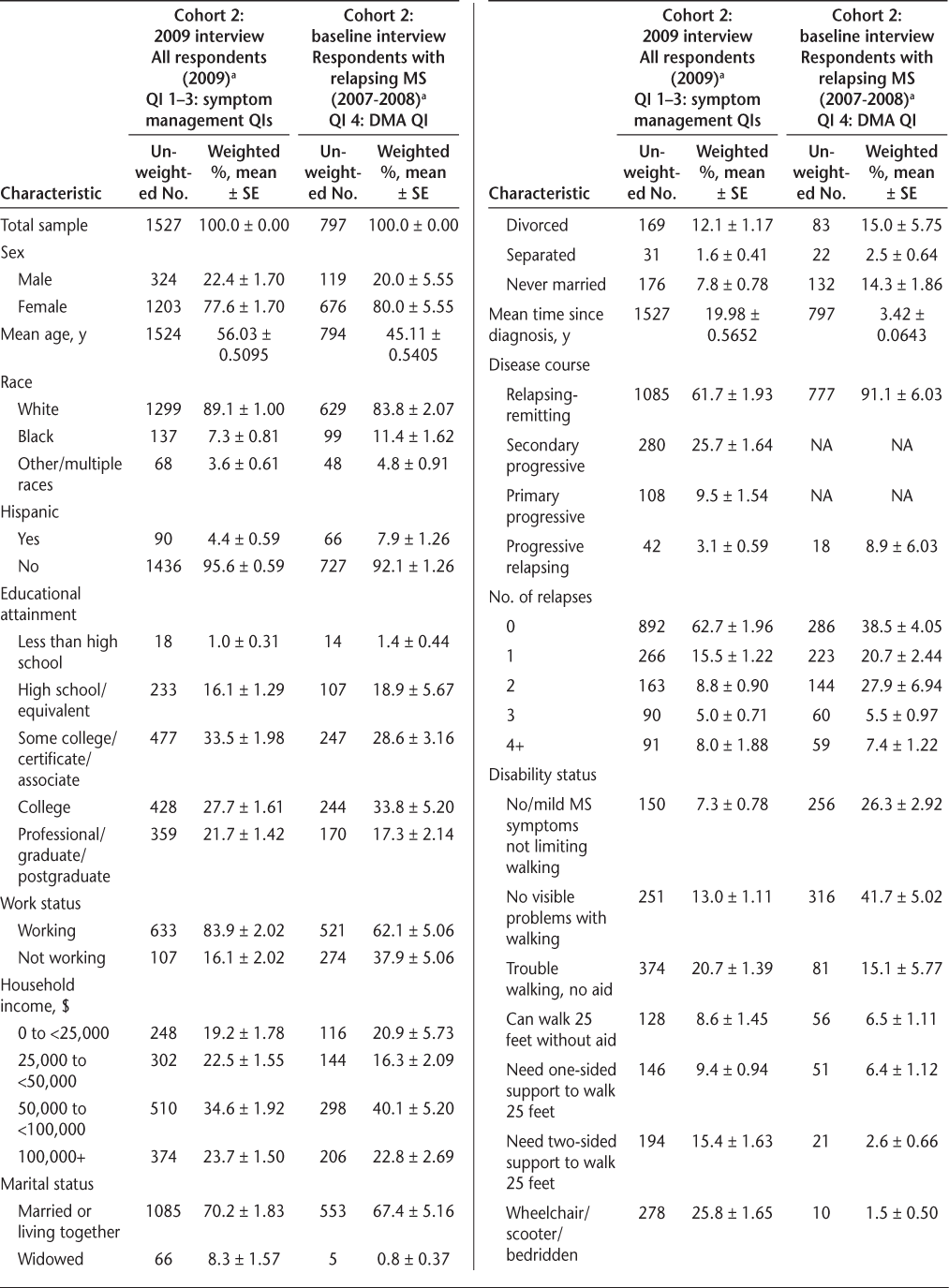

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics on the respondent characteristics of Slifka Study cohort 2 respondents used in the QI analyses. A subsample of the respondents from the cohort 2 baseline interview (ie, those with relapsing MS) was used for the DMA QI (QI 4). By design, this subsample—presented in the last two columns of Table 2—was more recently diagnosed, younger, and had only respondents with relapsing forms of MS compared with the entire cohort 2 2009 sample, shown in the first two columns of Table 2.

Characteristics of the Slifka Study cohort 2 respondents used in the QI analyses

Characteristics of the Slifka Study cohort 2 respondents used in the QI analyses (Continued)

QI Analysis Results

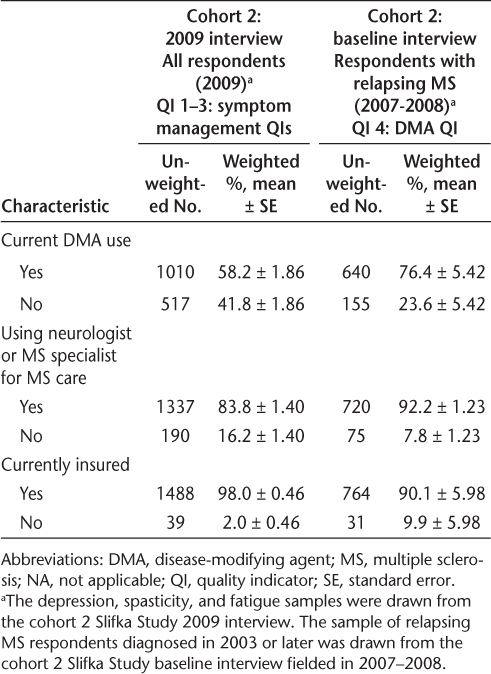

Table 3 presents the proportion of the diagnosed MS population that met each of the QIs (ie, the percentage of the denominator group that was treated) and describes the significant differences between the respondents who did not meet the QI and those who did.

Summary of QI findings

QI 1: Treatment of Depression

Among respondents who were diagnosed as having depression, two-thirds (66%, n = 344) met the QI (ie, received treatment for depression). Most of those received a medication (97%, n = 333; not shown), and approximately a third (30%, n = 103; not shown) received mental health services. As discussed previously herein, respondents could report multiple treatments. However, most of the treated respondents received only medication (70%, n = 241; not shown). Among depressed respondents with MS, those who were treated for depression were more likely to be of white and non-Hispanic race/ethnicity and have more severe disability compared with those who were untreated for depression.

QI 2: Management of Spasticity

Among respondents who were diagnosed as having spasticity, nearly two-thirds (66%, n = 614) met the QI (ie, received treatment for spasticity). Among those who received any treatment, 78% (n = 479; not shown) received a medication and 59% (n = 360; not shown) received rehabilitation services. Approximately a third (37%, n = 225; not shown) of the treated spasticity respondents received both rehabilitation services and medication, 41% (n = 254; not shown) were treated only with medication, and the remaining 22% (n = 135; not shown) received only rehabilitation services. Among respondents diagnosed as having spasticity, those who were treated were more likely to have higher educational attainment, fewer relapses, and more severe disability compared with those who were untreated for spasticity (Table 3).

QI 3: Management of Primary Fatigue

Unlike the other two diagnoses, a much smaller percentage of respondents diagnosed as having fatigue met the QI—just 23% (n = 272) of respondents diagnosed as having fatigue received a medication to manage their fatigue. Respondents diagnosed as having and treated for fatigue were more likely to be recently diagnosed, have a nonrelapsing MS diagnosis, be currently taking a DMA, have more severe disability, and be seeing a neurologist or MS specialist for their MS care compared with those who were untreated for fatigue (Table 3).

QI 4: DMAs for Relapsing Forms of MS

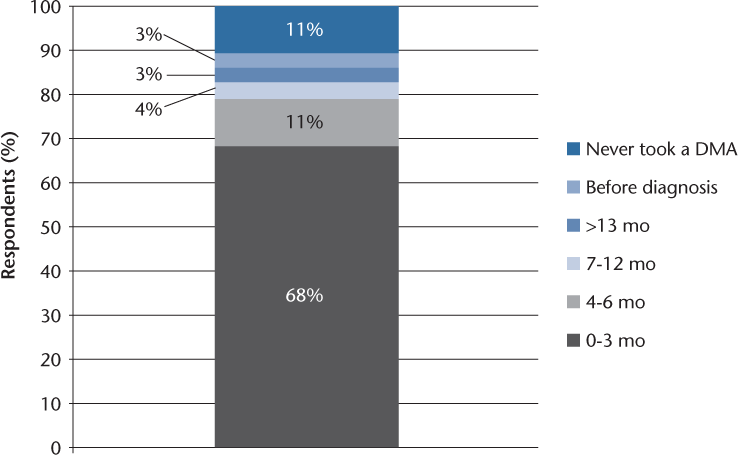

Among respondents diagnosed as having a relapsing form of MS since 2003, more than two-thirds (68%, n = 543) met the QI (ie, received a DMA within 3 months of their diagnosis). Respondents who met the QI were more likely to have higher educational attainment and income, be currently working and insured, be currently taking a DMA, be married, and be less severely disabled compared with those with a relapsing MS diagnosis since 2003 and not receiving a DMA within 3 months (Table 3).

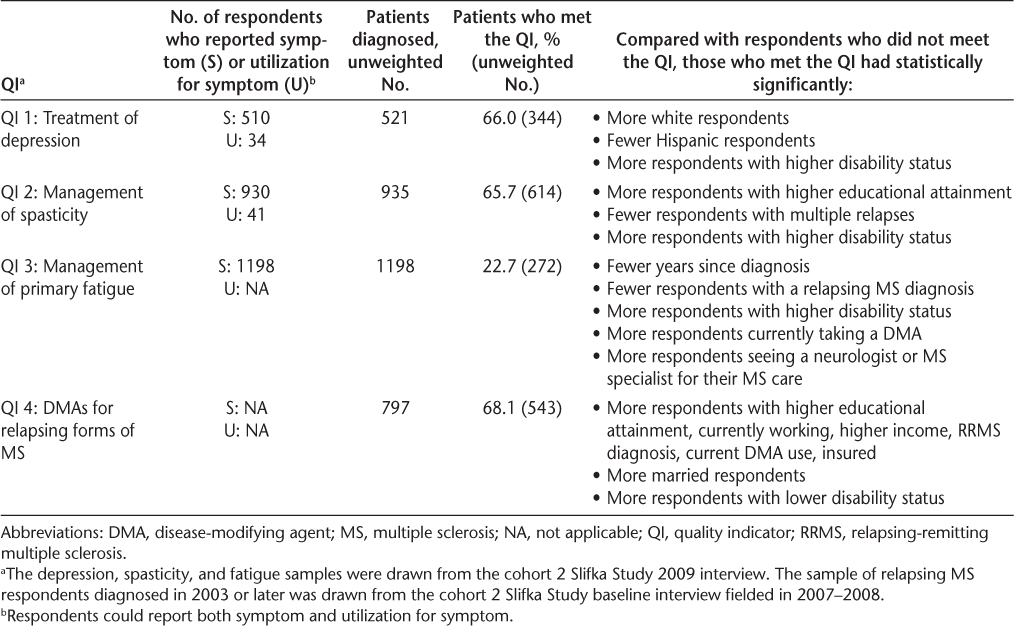

Among all people with a relapsing MS diagnosis since 2003, only 11% never received a DMA (top of stacked bar chart in Figure 1). Although the QI is for respondents to be offered a DMA within 3 months of diagnosis, we observed that 79% of respondents received a DMA within 6 months and 83% within 1 year. Interestingly, 3% reported receiving a DMA before their relapsing diagnosis. That is, in summary, most patients in the untreated group also received a DMA, but not necessarily within the 3 months as suggested by the clinical guidelines.

Time to disease-modifying agent (DMA) use in individuals with a relapsing multiple sclerosis diagnosis since 2003

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the extent to which individuals with MS meet any of the recently developed MS QIs. These findings, based solely on self-report data, could be used as a comparison for future studies using various other data sources. The results for three of the QIs—treatment of depression, management of spasticity, and DMA use within 3 months of a relapsing diagnosis—were fairly high, with more than 65% of respondents for each group meeting the respective QI. In contrast, a relatively low percentage of respondents diagnosed as having fatigue were found to be treated: 23%.

For the three QIs related to fatigue, depression, and spasticity, respondents who met the QI had a statistically significantly higher level of disability compared with respondents who did not meet the QI (for QI 4, this trend is reversed; see Table 3). There may be several potential explanations for why respondents with greater disability were more likely to receive treatment for their condition. For example, their symptoms are likely to be more severe, and they may be more visibly struggling to function, which could make the provider more inclined to offer symptomatic treatment, or the respondent may be more likely to bring up the symptom during the visit. They may also rely on a family or friend as a caregiver who is more actively involved in their care, whereas someone with less (but still some) disability may not perceive the need for a family or friend as a caregiver or to self-advocate for their own treatments. We also note that although the MS population is highly insured,9 for QI 4 (DMA use within 3 months of a relapsing diagnosis), we found that those who met the QI were significantly more likely to be insured than those who did not meet the QI.

Comparing these findings with previously published research, we found that the estimate of fatigue in people with MS is consistent with other researchers' estimates (eg, Braley and Chervin10 report 75%; we estimate 78.5%), but our estimate of symptomatic treatment for fatigue was lower (Hadjimichael et al.11 report 47.2% and 26.9% for respondents using and not using a DMA, respectively; we estimate 22.7% regardless of DMA use). Our estimate of the percentage of people with MS who have depression is also lower than other researchers' findings (Crawford and Webster12 report a 47%–54% prevalence of depression in the MS population compared with our estimate of 34.1%), whereas our estimate for the percentage of people with MS treated for depression is higher: Marrie et al.13 report depression treatment rates of 55.9% or 59.5% (depending on which instrument is used to define depression) compared with our estimate of 66.0%. Our estimate of people with MS with spasticity is also lower than that reported by Rizzo et al.14—84% compared with our estimate of 61.2%—although our treatment estimate for spasticity of 66% is comparable with theirs: 48% to 78%, varying by level of spasticity.

There are several potential reasons why our estimates may differ from those of other researchers. First, the other studies had different underlying patient populations. For example, Crawford and Webster's depression estimates were based on patients from a single MS comprehensive center in the Midwest, and Rizzo et al. used the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) patient registry.12 14 For symptomatic treatment rates, the difference may be due to how treatment is defined (eg, Hadjimichael et al.'s11 findings on pharmacologic treatment for fatigue included fluoxetine, an antidepressant, whereas ours did not).

As with other measurement efforts, measuring the quality of MS care based on the evidence and using existing data is challenging. For example, when assessing the fatigue QI, we were able to measure only medications as a treatment, of which there are relatively few. There are several nonpharmacologic treatments for fatigue that we were unable to measure because they are not collected by the Slifka Study. In addition, these QIs do not capture whether a patient previously tried a medication for fatigue or spasticity, for example, and found that the medication was ineffective or experienced adverse effects and thus discontinued the medication. Furthermore, QI 4 states that a DMA should be “offered,” yet we do not have data on the clinician-patient encounter, and, thus, we cannot ascertain whether treatment was offered early but delayed for various reasons. Therefore, our result for QI 4 is likely an underestimate of the actual number of patients offered a DMA within the first 3 months.

Although we used respondents' self-reports of receiving rehabilitation services as part of the definition of being treated for spasticity, the Slifka Study does not capture the reasons for receiving rehabilitation therapy. Therefore, our estimate for QI 2 may be an overestimate. That said, less than a fifth of the spasticity treated group reported receiving only rehabilitation therapies (n = 113), so it is not likely to be a large overestimate.

More broadly, we operationalized these QIs using the Sonya Slifka Study data, which provides robust, although imperfect, data on self-reported health-care utilization (eg, physician visits, psychotherapy, and rehabilitation). Self-reported data are susceptible to misunderstanding on the part of the interviewer and respondent, inconsistent findings compared with provider assessment, and recall bias. In addition, the Slifka Study does not collect data on symptom severity and perceived impact, which can greatly influence treatment decisions. We also did not have data on the indication for the medications, so we may be overestimating the percentage of patients who met the QI, for example, if a medication was prescribed for a different indication or symptom (eg, tricyclic antidepressants being prescribed for neuropathic pain in MS). Finally, we do not know whether this sample is representative of the MS population in the United States. In the absence of a probability-based sample, we used poststratification to approximate selection probabilities. Although it is imperfect (eg, time since diagnosis and age are not perfectly correlated), we view this as a practical approach to account for the Slifka Study's known oversampling design.

Despite the caveats discussed herein, this study provides an example of how data from a large patient cohort can be used to assess care quality in the MS population for a small subset of QIs. This analysis demonstrates that data from other sources are needed to fully assess quality of care. There are still many opportunities to improve the measurement of quality in MS care, including further operationalizing the QIs4 and testing them using data from claims or electronic health records, or developing more patient-reported outcomes in MS care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nicholas G. LaRocca, PhD, project officer, for his contributions throughout the project. June Halper, MSN, ANP, reviewed the drug lists used to operationalize QIs, helped determine which demographic variables were important to examine, reviewed study results, and provided input on the appropriateness of the study claims and implications.

PracticePoints

Quality indicators (QIs) for MS management were recently published, giving an opportunity to assess how important aspects of comprehensive care of MS are addressed in routine practice.

These study results—based on patient-reported data—provide preliminary insight into the fulfillment of QIs for MS management. However, additional data sources are needed to fully assess compliance with QIs.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Quality Indicators: introduction. http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov. Accessed May 15, 2014.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/browse/by-topic.aspx. Accessed May 15, 2014.

Douglas VC, Josephson SA. A proposed roadmap for inpatient neurology quality indicators. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1:8–15.

Cheng EM, Crandall CJ, Bever CT Jr, et al. Quality indicators for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010;16:970–980.

Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Perloffp J, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12:24–38.

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Treating MS: managing symptoms. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/Treating-MS/Medications#section-2. Accessed May 15, 2014.

Goodin DS, Frohman EM, Garmany GP Jr, et al. Disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Neurology. 2002;58:169–178.

Little RJ. Post-stratification: a modeler's perspective. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88:1001–1012.

Pozniak A, Hadden L, Rhodes W, Minden S. Change in perceived health insurance coverage among people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2014;16:132–139.

Braley TJ, Chervin RD. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment. Sleep. 2010;33:1061–1067.

Hadjimichael O, Vollmer T, Oleen-Burkey M; North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis. Fatigue characteristics in multiple sclerosis: the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:100.

Crawford P, Webster NJ. Assessment of depression in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2009;11:167–173.

Marrie RA, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Vollmer T. Validation of NARCOMS Depression Scale. Int J MS Care. 2008;10:81–84.

Rizzo MA, Hadjimichael OC, Preiningerova J, Vollmer TL. Prevalence and treatment of spasticity reported by multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2004;10:589–595.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Ms. Halper, who provided guidance on the manuscript, serves as a consultant to Biogen Idec on a research project.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) research contract No. HC0135. Ms. Halper received funding from Abt Associates for her consultation through NMSS research contract No. HC0135. The Slifka Study, from which these data were drawn, was also funded by the NMSS. Abt Associates, a for-profit organization, was contracted and paid by the NMSS for work on the Slifka Study. All the coauthors received a salary for previous work on the Slifka Study.