Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Case Report: Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder as the First Manifestation of Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Abstract

Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a parasomnia characterized by brief recurrent episodes of loss of muscle atonia during rapid eye movement sleep, with enacted dreams that cause sleep disruption. Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have an increased risk compared with the general population to be affected by a sleep disturbance, including RBD. Patients affected, however, uncommonly can present RBD as the first clinical manifestation of MS without other neurologic deficits. These clinical presentations have usually been attributed to inflammatory lesions in the pedunculopontine nuclei, located in the dorsal pons. We present a case of RBD in a 38-year-old woman who was later diagnosed as having MS due to imaging findings and development of focal neurologic deficits. MS should be considered among the differential diagnoses in patients who present with symptoms of RBD, particularly if they are young and female.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease mediated by immune cells that promote demyelination, gliosis, and neuroaxonal degeneration in the brain and spinal cord and that ultimately may lead to a neurodegenerative process.1 2 Both genetic and environmental factors may trigger the immune dysregulation characteristic of this disease, but the exact cause remains unclear. Approximately 2.5 million individuals worldwide are affected by MS.1 Prevalence is highest in higher latitude countries (far from the equator), such as northern Europe, southern Australia, and the middle of North America.2 3 Multiple sclerosis is a principal cause of disability in young adults. Average age at disease onset is 30 years, and it affects more women than men (2:1).3 4 Clinical presentation and progression of the disease vary according to the affected location in the central nervous system.1 Common initial symptoms are fatigue, paresthesia, weakness, diplopia, vertigo, unilateral painful loss of vision, and ataxia. Among other symptoms reported, sleep disorders are a big concern. Herein we describe an atypical case of a woman presenting with a rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) as the initial manifestation of MS. Ethics approval was not required from the institutional review board because this is a case report. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this article.

Case Presentation

A 38-year-old woman presented to the neurology service with a 1-year history of frequent episodic movements during sleep. Her husband noted that during sleep the patient presents somniloquy and that from 2 to 4 am she has sudden strong movements in all her extremities, which have generated bodily harm to herself or to him. The patient is not conscious of these movements, but when her husband wakes her up she remembers exactly what she was dreaming. Dream content was usually scenes that generated terror, such as those from horror movies previously seen. She had consulted many physicians but had no specific diagnosis or treatment. She additionally noted that in the past 3 months she has had occasional paresthesia in her hands and feet and certain difficulties performing fine movements of her fingers, with no weakness. She denies having constipation or incontinency, speech disturbances, swallowing problems, and mood alterations.

She did not present any relevant medical history. She was taking oral contraceptives and denied taking any other medications. She denied smoking and did not present any relevant family history of disease. At neurologic examination she was alert and oriented, with no speech impairment. Her cranial nerves did not show any alterations. Results of motor and sensory examinations were normal in all four extremities. Coordination and gait were normal.

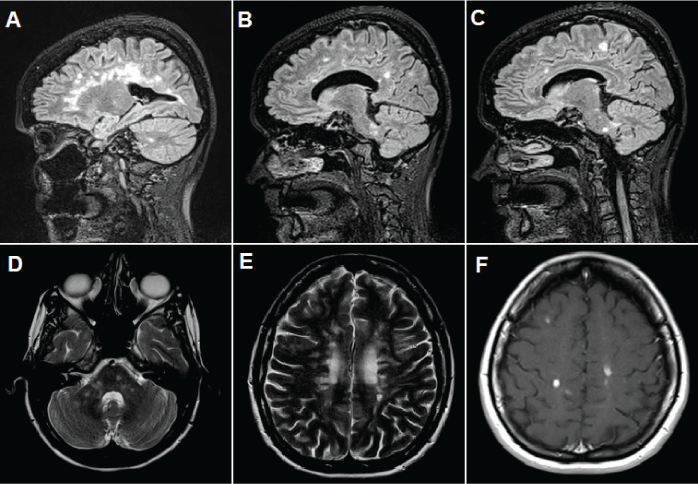

An RBD was considered, and a polysomnographic recording that was performed at another institution confirmed this diagnosis by showing electromyographic activity with excessive twitching observed in the tibialis anterior muscle and the flexor muscles of the hand in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. However, no reported movements were seen during REM sleep. Other sleep disorders, such as parasomnias and obstructive sleep apnea (her reported apnea-hypopnea index was 1.4 per hour of sleep), were ruled out. She had normal levels of thyrotropin and vitamin B12; results of antinuclear antibody, anti–double-stranded DNA, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1, and human immunodeficiency virus testing were negative. Brain magnetic resonance imaging was performed (Figure 1) and revealed multiple perpendicular demyelinating lesions in the corpus callosum and the periventricular and juxtacortical regions. There were also lesions in the pons, bilateral cerebellar peduncles, and hemispheres. There was contrast enhancement of punctiform lesions in the bilateral frontoparietal regions and right inferior cerebellar peduncle and some in the periventricular region.

Brain magnetic resonance images

A lumbar puncture was performed. Results of cerebral spinal fluid cytologic analysis were normal. There were positive oligoclonal bands with a type 2 pattern. The isoelectric focusing method showed more than five well-defined bands in the cerebral spinal fluid that were not present in paired serum.

An MS diagnosis was established, and, due to its active nature and the high lesion load of the disease, treatment with fingolimod, 0.5 mg/d, was initiated, with 0.5 mg of clonazepam at night for RBD.

At the 6-month follow-up visit, the patient noted that she had had a remission of her RBD symptoms. She had adhered to the fingolimod treatment but had suspended clonazepam use owing to daytime sleepiness. A follow-up brain magnetic resonance image revealed no significant change in the number of demyelinating lesions, and there were no lesions enhanced by contrast or with diffusion restriction that suggested disease activity. At 1-year clinical follow-up the patient has remained stable, with no relapses of MS or RBD.

Discussion

Sleep disturbances are far more common in patients with MS than in the general population; they greatly decrease the quality of life of these patients.5–8 The reported prevalence of sleep disturbances in patients with MS ranges from 24% to 61%5–15compared with 33.1% in the general population.9 In addition, women with MS seem to be more susceptible to sleep disorders than men with MS.9 Interestingly, poor sleep quality has been linked to a heightened risk of other comorbidities in patients with MS, such as pain, depression, fatigue, heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and an overall increase in mortality.2,6,9–11 In people who have chronic illnesses, sleep disorders may increase disease impact and are associated with lower work productivity, worse mental health, and higher use of health care services.9

Sleep disturbances comprise a wide variety of disorders, and it is essential to recognize the specific disorder because they can be treated. Sleep disorders reported in MS include insomnia (40%–54%), sleep-disordered breathing (14%–58.1%), restless legs syndrome (14%–57.5%), and RBD (0.38%–3.2%).5,10–12,16,17

Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder is a parasomnia characterized by recurrent episodes of loss of muscle atonia during REM sleep (mainly in the second half of the night), with enacted dreams (generally violent, action-filled, or unpleasant dreams) that cause sleep disruption, abnormal motor or verbal behavior, and occasional bodily harm to oneself or to a sleeping partner in response to the specific dream content.10–12,18,19 Complex behaviors have been noted (eg, talking, laughing, shouting, swearing, gesturing, punching, and kicking during sleep).18 If awakened shortly after the event, the individuals usually remember what they were dreaming about and what they were trying to do.18 Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder not associated with MS is quite different: age at onset usually is older than 50 years, and men are more likely to be affected than women, constituting 80% to 90% of cases.18

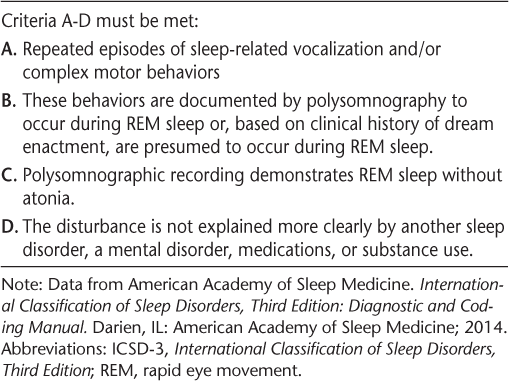

The etiology of RBD might be idiopathic,20 or RBD may develop secondary to an underlying neurologic disease.11,18,21 The idiopathic form (Table 1) of RBD has, however, been challenged because many authors have suggested that this may be a precursor syndrome of neurodegenerative disorders (often following a delay of decades).19 In well-characterized cohorts, 50% to 70% of individuals with idiopathic RBD eventually evolve toward a clearly established α-synucleinopathy (Parkinson disease, Lewy body dementia, multiple systems atrophy) during a 10- to 15-year period.18 19

Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder from the ICSD-3 20

Many other neurodegenerative disorders have been associated with the secondary form of RBD, such as olivopontocerebellar degeneration and multi-infarct dementia, among others.5,12,18 Interestingly, sleep is implicated in brain plasticity, a process impaired in these neurodegenerative diseases.9

Other causes of secondary RBD have been associated, such as genetic diseases (Machado-Joseph disease, Moebius syndrome, etc.), focal brainstem lesions (MS, tumor, stroke), nonfocal lesions (epilepsy, autism, limbic encephalitis, etc.), and substance induced (tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, mirtazapine, alcohol, caffeine).18

The diagnosis of RBD is usually made according to the patient's history (via precise description of events by a reliable eyewitness and corroboration of the dream content by the patient) and is confirmed via a polysomnographic recording.18 When abnormal behaviors of dream enactment do not happen overnight, polysomnography can still establish the diagnosis of lack of REM sleep atonia by showing increased REM sleep motor tone and/or increased phasic motor activity.19

The differential diagnosis of RBD includes nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, non-REM sleep parasomnias (sleepwalking and sleep terrors), and other REM parasomnias (such as sleep paralysis, nightmare disorder, and sleep-related hallucinations).18 Careful review of the patient's nocturnal episodes, ideally with the help of a sleeping partner, can aid in differentiating RBD from other sleep disorders.19

Physiologically, the usual suppression of motor activity during normal REM sleep results from multiple interacting nuclei and pathways that initiate in the brainstem. Important brainstem nuclei include REM-off nuclei (the ventral lateral portion of the periaqueductal gray matter and the lateral pontine tegmentum) and REM-on nuclei (precoeruleus and sublaterodorsal nucleus, locus coeruleus, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus, pedunculopontine nucleus, and raphe nucleus).19,22,23 The REM-on and REM-off distinction is based on higher activity during either REM sleep or non-REM sleep and waking.23

Most REM-on neurons synthesize glutamate and directly recruit inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid and glycine-containing spinal interneurons, causing active inhibition of muscle activity in REM sleep by suppressing α-motoneuron activity in the anterior horn of the spinal cord.18 23 An indirect pathway is also hypothesized, which suggests that the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus neurons project to the magnocellular reticular formation and from there to spinal interneurons via the ventrolateral reticulospinal tract.23 Lesions of the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus decrease activation of spinal interneurons, manifesting as a lack of muscle tone inhibition.18,22,24 Atonia during REM sleep is reinforced by reduced excitatory input of glutamatergic, noradrenergic, serotoninergic, dopaminergic, and hypocretinergic stimulation to the α-motoneurons.23 Interestingly, midbrain and forebrain structures have also been tied to this complex circuitry, including the substantia nigra, hypothalamus, thalamus, basal forebrain, and frontal cortex.22 23

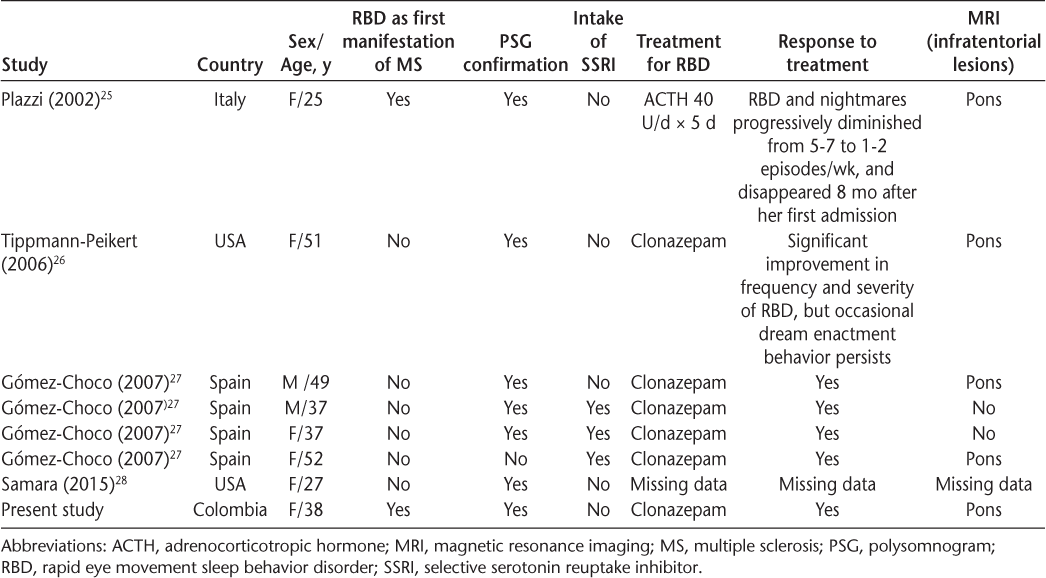

Previous case reports have described RBD symptoms in relation to acute MS attacks25–28 and, uncommonly, as the first clinical manifestation in patients with MS (Table 2). These clinical presentations have usually been attributed to lesions in the pedunculopontine nuclei, located in the dorsal pons (pontine tegmentum), that supply the locus coeruleus and reticular formation.5,10,11 This would explain the higher prevalence of RBD in patients with MS compared with the general population, because demyelinating lesions in the brainstem are frequent in patients MS.16

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with MS reported in the literature with diagnosis of RBD

The present patient had a dorsal pontine lesion that could explain the origin of RBD. The location of lesions associated with RBD in MS is, however, controversial, probably owing to the complex circuitry that controls this physiologic process. Gómez-Choco et al.16 reported that of three patients with confirmed RBD, only one had a pontine lesion.

Note that, generally, patients with MS do not consult a physician because of RBD and, when they do consult, RBD symptoms are frequently subtle and not disclosed to health care professionals; patients will also try to prevent sleep-related injury (eg, by sleeping on a floor in a room without furniture) years before seeking medical attention.16 19 Clinicians should, therefore, routinely ask about sleep disorders in patients with MS owing to their higher prevalence in such patients and the potential effect of sleep on overall disease impact.

It is necessary to administer the appropriate treatment to improve the sleep and quality of life of these patients.9 The initial goal in RBD therapy is to protect the patient and sleeping partner by adjusting the sleeping environment. Sleeping partners should sleep separately until the dream enactment behavior is under control; the bed should be distanced from a window, and all bedside objects that could cause injury (eg, night table, lamps, firearms) should be removed.19 In idiopathic RBD, the first-line symptomatic treatment is clonazepam and/or melatonin.19,21,23 The mechanism of action seems to be related to its ability to reduce phasic activity in REM sleep.18 A dose of 0.5 to 2 mg of clonazepam is usually effective.18 Melatonin should be given in doses of 6 to 15 mg nightly to reestablish normal REM atonia.19 29 Unfortunately, randomized controlled trials of pharmacologic treatments are unavailable.11 It is also necessary to control the inflammation cascade in RBD associated with an acute MS relapse with a course of corticosteroids or other immunomodulatory therapies to potentially expedite the patient's recovery.5 It should be clear, however, that corticosteroids are suggested only for acute relapses/inflammation' and not as a primary treatment for RBD symptoms in MS of longer or unclear duration. It is important to remember that antidepressant agents should be avoided/discontinued because they can either precipitate, aggravate, or unmask RBD.11

In conclusion, the presenting syndrome in patients with MS may be RBD, as in the patient described herein. This constitutes a clinical challenge for the neurologist. Multiple sclerosis should be considered among the differential diagnoses in patients who present with symptoms of RBD, especially if they are young and female.

PRACTICE POINTS

Symptoms of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder are frequently subtle and not disclosed to health care professionals.

MS should be considered among the differential diagnoses in patients who present with symptoms of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, particularly if they are young and female.

Clinicians should routinely ask about sleep disorders in patients with MS.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Helen Reina for her assistance in copyediting the manuscript.

References

Dendrou CA, Fugger L, Friese MA. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:545–558.

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–1517.

World Health Organization. Atlas: multiple sclerosis resources in the world 2008. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43968/1/9789241563758_eng.pdf. Accessed: April 2017.

Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:938–952.

Caminero A, Bartolomé M. Sleep disturbances in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2011;309:86–91.

Gamaldo CE, Shaikh AK, McArthur JC. The sleep-immunity relationship. Neurol Clin. 2012;30:1313–1343.

Merlino G, Fratticci L, Lenchig C, Picello M, et al. Prevalence of “poor sleep” among patients with multiple sclerosis: an independent predictor of mental and physical status. Sleep Med. 2009;10:26–34.

Neau J-P, Paquereau J, Auche V, et al. Sleep disorders and multiple sclerosis: a clinical and polysomnography study. Eur Neurol. 2012;68:8–15.

Bamer AM, Johnson KL, Amtmann D, Kraft GH. Prevalence of sleep problems in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008;14:1127–1130.

Barun B. Pathophysiological background and clinical characteristics of sleep disorders in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(suppl 1):82S–85S.

Brass SD, Duquette P, Proulx-Therrien J, Auerbach S. Sleep disorders in patients with multiple sclerosis. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:121–129.

Fleming WE, Pollak CP. Sleep disorders in multiple sclerosis. Semin Neurol. 2005;25:64–68.

Lobentanz IS, Asenbaum S, Vass K, et al. Factors influencing quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: disability, depressive mood, fatigue and sleep quality. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;110:6–13.

Chen J-H, Liu X-Q, Sun H-Y, Huang Y. Sleep disorders in multiple sclerosis in China: clinical, polysomnography study, and review of the literature. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2014;31:375–381.

Pokryszko-Dragan A, Bilńska M, Gruszka E, Biel Ł, Kamińska K, Konieczna K. Sleep disturbances in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2013;34:1291–1296.

Gómez-Choco MJ, Iranzo A, Blanco Y, Graus F, Santamaria J, Saiz A. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and REM sleep behavior disorder in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:805–808.

Marrie RA, Reider N, Cohen J, et al. A systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of sleep disorders and seizure disorders in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21:342–349.

Frenette E. REM sleep behavior disorder. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:593–614.

Howell MJ, Schenck CH. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and neurodegenerative disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:707–712.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

Lunde HMB, Bjorvatn B, Myhr K-M, Bø L. Clinical assessment and management of sleep disorders in multiple sclerosis: a literature review. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2013;196:24–30.

Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder: updated review of the core features, the REM sleep behavior disorder-neurodegenerative disease association, evolving concepts, controversies, and future directions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:15–54.

Peever J, Luppi P-H, Montplaisir J. Breakdown in REM sleep circuitry underlies REM sleep behavior disorder. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:279–288.

Boeve BF, Silber MH, Saper CB, et al. Pathophysiology of REM sleep behaviour disorder and relevance to neurodegenerative disease. Brain. 2007;130(pt 11):2770–2788.

Plazzi G, Montagna P. Remitting REM sleep behavior disorder as the initial sign of multiple sclerosis. Sleep Med. 2002;3:437–439.

Tippmann-Peikert M, Boeve BF, Keegan BM. REM sleep behavior disorder initiated by acute brainstem multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2006;66:1277–1279.

Gómez-Choco MJ, Iranzo A, Blanco Y, Graus F, Santamaria J, Saiz A. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and REM sleep behavior disorder in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:805–808.

Samara D, Karnib H, Kaplish N, Braley T. REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) in a multiple sclerosis patient. Sleep. 2015;38:A445.

Braley TJ, Chervin RD. A practical approach to the diagnosis and management of sleep disorders in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2015;8:294–310.