Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Barriers and Facilitators Related to Breast Cancer Screening

Recent literature indicates that women with various types of chronic disabling conditions are less likely to participate in routine breast cancer screening than those without disabling conditions. The purpose of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators related to breast cancer screening among women with multiple sclerosis (MS). A total of 36 women with MS, whose mean age was 55 years, participated in a semistructured interview in a private setting. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The interview questions, informed by the Health Belief Model, addressed knowledge, experience, barriers, and facilitators related to breast cancer screening. Qualitative descriptive techniques were used to analyze the data. About 94% of the women in the sample were white, 67% were married, 47% had at least a bachelor's degree, and 31% were unemployed because of their disability. The results showed that 70% of these women had received annual mammograms and 50% had performed monthly breast self-examinations. Of the women who had not received mammograms, most (80%) had mobility limitations. Some of the women in this study described various environmental and intrapersonal barriers to breast cancer screening. Among these were barriers related to transportation, difficulty in positioning for the examination, health-care provider attitudes, not remembering, fear, discomfort, and “having enough to handle.” Facilitators included annual reminders and helpful health-care providers.

In 2009 there were approximately 192,000 new diagnoses of breast cancer and 47,000 deaths among women in the United States, making breast cancer one of the leading killers of American women.1 Evidence shows that early detection through breast cancer screening—including mammography, clinical breast examinations, and, to some degree, breast self-examination (BSE)—can effectively reduce the overall breast cancer mortality rate.1 2 When diagnosed early, the 5-year survival rate for breast cancer may be as high as 98%.1

As is the case for many vulnerable populations such as minority women and women of low socioeconomic status, the need for health promotion, including breast cancer screening, for women with chronic disabling conditions is often overlooked.3 4 Compared with other underserved populations, there has been relatively little research on breast cancer screening among women with disabling conditions.3 Research suggests that women with disabilities, especially older women (>65 years old) with multiple functional limitations, are less likely to engage in breast cancer screening as well as other health-promoting behaviors compared with women with no disabilities.5–7 This underuse of breast cancer screening may contribute to the higher rates of diagnosis of later-stage breast cancer, which translates to an increased mortality rate among women with disabilities.8 This disparity in breast cancer screening has particular implications for women with multiple sclerosis (MS), who may be at a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer.9

The multiple obstacles faced by women with chronic disabling conditions as they attempt to navigate an often cumbersome health-care system may contribute to the underuse of breast cancer screening among this group of women. Some of the barriers reported by these women include inadequate transportation, inaccessible breast centers, mammogram machines that fail to accommodate women with mobility impairments, and insensitive treatment by health-care providers (HCPs).10–12 Liu and Clark13 found that because of negative mammography experiences, women with disabilities were less likely to adhere to regularly scheduled screening than women without disabilities. It is imperative to understand the barriers faced by these women that contribute to this underuse of breast cancer screening. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to elucidate both the barriers and facilitators related to mammography and BSE experienced by women with MS.

Methods

This study used a qualitative descriptive design to summarize perceived barriers and facilitators related to breast cancer screening (mammography and BSE) among women with MS in their everyday language.14 Thus, this study provides basic descriptions in the words of the women themselves by presenting the facts with limited interpretation.14 This methodological approach is useful in providing HCPs with answers to questions regarding breast cancer screening among this population, whose needs are often ignored.

Data Collection

After institutional review board approval was obtained, theoretical nonprobability sampling was used to recruit women for the study. The recruitment process involved asking women participating in a longitudinal study of health promotion and quality of life of persons with MS if they were interested in participating in an interview regarding their experiences and attitudes about breast cancer screening (mammography and BSE). Before the interview, written consent was obtained from the women following an explanation of the study. A semistructured interview using primarily open-ended questions was conducted in a private setting. The interviews, lasting 10 to 45 minutes, included questions about knowledge, experience, and perceived barriers and facilitators related to breast cancer screening. To ensure accuracy, the interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Field notes primarily describing the tone and context of the interviews were documented after each interview. Field notes contribute to the audit trail, thereby enhancing trustworthiness.15

Data Analysis

Qualitative content analysis was used to analyze the interview data, following the method described by Lincoln and Guba.15 16 First, the audiotaped interview was transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy by the researcher. The text was then read repeatedly, line by line. Phrases and sentences that had distinct narrative meanings (meaning units) were highlighted, and codes were placed in the margins. These codes were condensed versions of the meaning units. The researcher then reviewed the codes with another researcher until consensus was reached. Upon mutual agreement of the researchers, the codes were grouped into clusters and then structured into categories and subcategories that summarized the women's perceptions of breast cancer screening barriers and facilitators, in their own words.14 The categories were derived individually for mammography and BSE, as the two types of screening procedures are unique and thus may have different barriers and facilitators.

Several steps were taken to ensure trustworthiness of the study. The transcribed interviews were reviewed by a second researcher who closely adhered to the methodology as described and developed an audit trail for reproducibility.

Findings

The purposive convenience sample included 36 women with MS who were participating in an ongoing longitudinal study of health-promotion beliefs and practices of people with MS living in the southwestern United States. The women ranged in age from 30 to 80 years (mean [SD] age, 55.03 [10.56] years). The criteria for breast cancer screening used for this study are based on the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommendations of yearly mammograms and clinical breast examinations starting at age 40, clinical breast examinations every 3 years for women aged 20 to 39, and regular BSE to identify changes in breast tissue.1 Because three of the women in this study were younger than 40 and therefore did not meet the minimum age requirement for a screening mammogram as recommended by the ACS,1 their responses were not used for the mammography analysis.

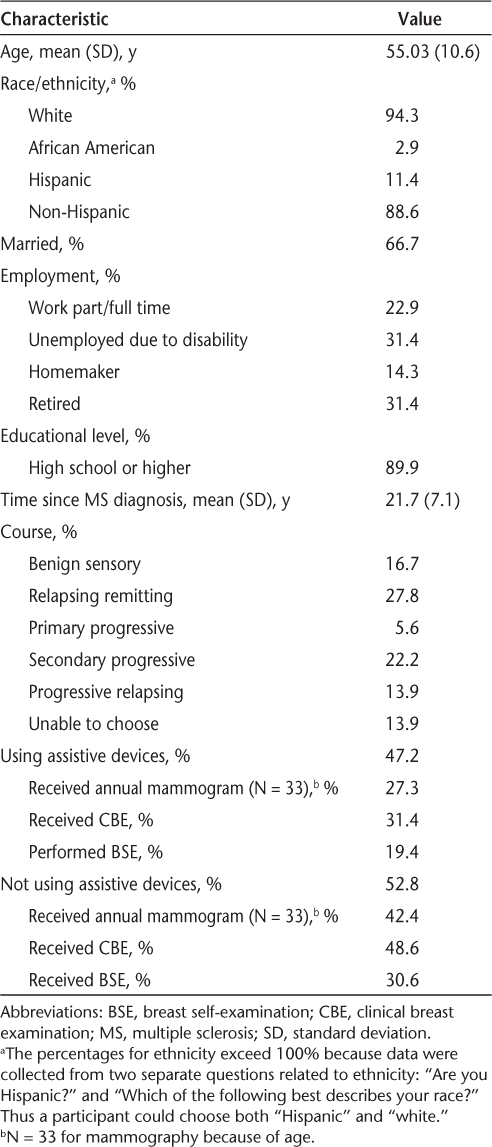

The majority of the women were white (94.3%) and married (66.7%); almost half (47.2%) had a bachelor's degree or higher. The average duration since diagnosis with MS was 21.7 years. Almost half (47.2%) of the women reported using some form of mobility assistance such as a cane, walker, wheelchair, or scooter. About 63% of the women were either unemployed due to their disability or retired (Table 1).

Characteristics of study participants (N = 36)

Most of the women in this study (69.7%) reported that they obtained routine annual mammograms, and 50% reported performing monthly BSE. However, only 53% of the women with mobility impairments received an annual mammogram. Notably, among the women who did not get annual mammograms, 80% had mobility impairments requiring an assistive device such as a wheelchair, cane, or rollator.

With respect to mammography, more than half (57%) of the women voiced concerns regarding at least one barrier to obtaining mammograms. Over one-third (36%) of the women reported difficulties with performing monthly BSE.

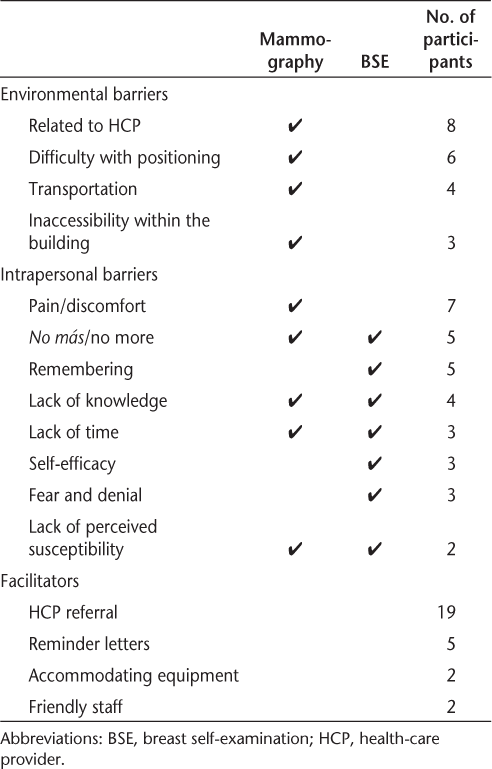

Two main categories related to mammography emerged from the categorical data analysis of the interviews: “environmental barriers” and “intrapersonal barriers.” Within the “environmental barriers” category for mammography, there were four subcategories: “inaccessibility within the building,” “difficulty with positioning,” “transportation,” and “related to health-care provider (HCP).” The “intrapersonal barriers” category emerged for both mammography and BSE, and many of the subcategories that emerged for mammography overlapped with BSE. These included “lack of time,” “lack of knowledge” (regarding insurance coverage for mammography and procedural knowledge for BSE), “lack of perceived susceptibility,” and “no más,” meaning “no more” (referring to the concept of having enough to deal with in terms of health challenges). The subcategory “pain/discomfort” was an intrapersonal barrier that applied only to mammography. Unique to BSE were the categories “remembering,” “self-efficacy,” and “fear and denial” (Table 2).

Barriers and facilitators related to mammography and BSE

Environmental Barriers

Environmental barriers are the external factors that negatively affect a woman's ability to gain access to and navigate within the health-care facility. These include obstacles stemming from the interaction between the woman and the health-care system. Most of the women in this study (70%) did not report experiencing any environmental barriers to mammography. However, of the 30% of the women who reported having difficulties in getting mammograms, over 60% of them used assistive devices because of their physical limitations.

Related to Health-Care Provider

Barriers related to HCPs include obstacles directly created by HCPs. One barrier, HCP attitudes, refers to the manner in which technicians and other HCPs treat women at health-care facilities, including breast centers and doctors' offices, a concern expressed by four of the women. Some of the women said that some technicians performing mammography were not sensitive or knowledgeable about their special needs. “You know they just don't know how to deal with, adapt to handicapped people. I mean they are so used to running a factory through, that they just see the cane and they say, ‘well for whatever reason she needs it, we're gonna handle as normal.’” Another woman who used a scooter reported being treated like a child and said that a technician was “rude,” commenting that she was not used to “dressing children” when she was asked to help the woman with dressing. As a result of this experience, the woman did not return for a mammogram for another 10 years.

Another obstacle to mammography screening is the lack of referral or recommendation for screening by an HCP. Although women do not need a physician's order for a screening mammogram, women are more likely to seek a mammogram if they have had an HCP referral or recommendation.3 All the women in this study who had obtained their annual mammograms had done so through physician referrals. However, some women reported that their physician failed to recommend mammography, and one woman did not have a physician to give her a recommendation.

Difficulty with Positioning

Many of the mammography machines require that women stand for the procedure, but women with MS are often unable to stand for the extended period of time necessary. Difficulty with positioning for the mammogram procedure was the most commonly reported environmental barrier. “It's difficult to stand up and hang onto the machine, which without my cane, I'm very insecure.” One woman reported that because of her inability to stand, “it was near impossible to do it.” Women using wheelchairs are especially affected by positioning hurdles; although some of the newer mammogram machines can be lowered to accommodate women in wheelchairs, in some instances they cannot be lowered sufficiently. This creates a particularly challenging situation for both the woman and the mammography technician. One participant stated, “I'm in a wheelchair and sometimes it's a little harder to sit up straight because it doesn't meet me exactly where I am.”

Transportation

Transportation barriers are obstacles related to getting to and from the mammogram facility. Some women voiced concerns about the inconvenience of getting to the mammogram facility. This inconvenience played a role in one woman's decision not to get a mammogram: “At this point, it's just, it's inconvenient to have to worry about how to get from point A to point B, especially if it's more than 15 steps.” Some of the transportation concerns were directly related to MS symptoms such as fatigue and visual impairment. One woman reported that MS was the source of her transportation problems, as she didn't feel confident in her ability to safely navigate the large metropolitan area in which she lived. “It's a barrier, cause getting there, my MS is a problem . . . transportation, I get tired. I try not to drive the freeways anymore because I don't feel my reaction time or my vision is well enough for me to drive this freeway.”

Inaccessibility Within the Building

Inaccessibility within the building refers to barriers related to the built environment of the mammography facility. Some cancer screening facilities are not easy to access, with heavy doors and small changing rooms. A few of the women in this study discussed having difficulty with accessibility in the changing rooms, where the lockers were not positioned within their reach, making it impossible to independently change their clothes for the mammogram. One woman said, “The actual room that they say ‘go on in and then put it in a locker’ is not even at my arm's length.” Another woman voiced her concern about accessing the building by stating that “it's physically difficult . . . it's an aggravation.”

Intrapersonal Barriers

Intrapersonal barriers are internal, individual factors that may prevent or reduce the likelihood of mammography and BSE. Unlike environmental obstacles, intrapersonal barriers are intrinsic to the person and therefore reflect the person's own perception of experiences. These types of barriers were applicable to both mammography and BSE. Only 33% of the women in this study indicated having obstacles in this category.

Pain/Discomfort

Experiencing pain or discomfort associated with mammography was the most commonly reported barrier to mammography (n = 7), including among those who obtained regular screening. Some of the women described mammograms as “cold,” “embarrassing,” “quite painful,” and even “harmful . . . and next door to excruciating.” One woman who used a wheelchair and experienced mammogram equipment that did not fully accommodate her needs said, “It's just uncomfortable with my chair to get close enough.” Another woman stated, “I hate it. It hurts.”

With regard to BSE, one woman was uncomfortable with the idea of performing BSE. She reported [with a grimacing face] that she “didn't like the idea of massaging my breast” and later said it was “embarrassing” to her, which is why she did not think about doing BSE.

No Más/No More

Several women in the study indicated that they had “enough to deal with” because of the multiple demands associated with managing their MS as well as their daily stressors, making the prospect of having to “handle” another chronic illness (breast cancer) unthinkable. This feeling can lead to avoidance of screening. This category, “no más,” or “no more,” can be viewed as a barrier to breast cancer screening. Five women reported the notion of no más related to both mammograms and BSE. The following quotes by women exemplify this concept: “I've decided that I have MS and that's enough. I don't need to have breast cancer. I shouldn't [with emphasis] have to deal with breast cancer too! I deal with MS!” “I like, I've got enough to deal with my, with my MS, like I don't want anything else to deal with. Let me do my own thing and just not have to worry about anything.” A 43-year-old working mother of four children expressed that she had not gone to have a mammogram because of the multiple stressors in her life. She said that having MS was a “big factor” in delaying her screening. During the interview, she discussed all the burdens she was experiencing raising children, working, and managing her challenges due to her functional decline. She said regarding mammography, “On the one hand I want to know. On the other hand, I don't want to know because I'm still not dealing with my MS.”

Remembering

Remembering to perform BSE can also be considered a barrier to screening. This was the most common intra-personal barrier related to BSE for these women, with five individuals reporting that this was an issue for them. Three women said they “just don't think about it,” and one said she had trouble “reminding” herself to do it: “It's not something that I guess I can remember to do, so I've never gotten into the habit of it. My mind leaves me and I forget things.”

Lack of Knowledge

Not knowing about health insurance coverage for mammography was a concern for a few of the women. A couple of the women reported that their Medicare insurance covered gynecologic exams only every other year and that “they limit (overall) the number of times that you can have it (mammography).” The fact that most insurance plans, including Medicare and Medic-aid, cover annual mammograms and that these women were unaware of this coverage makes this barrier a “lack of knowledge” barrier. With regard to BSE, a woman reported, “I really don't know exactly how to do it.” And another woman was not aware of when to do the BSE and stated, “I just go to the doctor once a year and hopefully that is enough.”

Lack of Time

Being too busy and having time constraints was a concern for some women with regard to both BSE and annual mammography screening. One woman reported that she had been working and “just didn't have time.” Another woman said concerning BSE, “I'm so busy with the kids and work and . . . like I have no time. It's just not one of the things on my list to do with all the other stuff that I'm doing.”

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to feeling capable of accomplishing a behavior,17 in this case BSE. Three of the women reported a lack of confidence in their ability to perform BSE: “My hands are mostly numb, so I don't know that I would be as good at it as I used to be.” One woman was concerned about “being able to have an educated fingertip to discern which is which [cancer vs. fibrocystic tissue].”

Fear and Denial

With regard to BSE, the women in this study expressed that fear and denial played a role in their non-participation. One woman said, “It's either forget about it, deny that I, well you know, you have this, I have this fear that if I check for it and I find something then my life is gonna change. But if I don't check, I don't find anything and nothing changes.”

Lack of Perceived Susceptibility

Two women did not perceive that they were at risk for developing breast cancer. One 80-year-old woman, unaware of the fact that she was at a higher risk for developing breast cancer because her sister had a history of ovarian cancer, stated that she “probably wouldn't get it” because she had “lived this long without cancer.” Another woman said she was not “motivated” to do BSE and stated, “I'm obviously not scared that I have breast cancer or afraid that I might develop breast cancer.”

Facilitators of Mammography

Facilitators are factors that enhance the likelihood that a woman will engage in breast cancer screening. Having an annual clinical breast examination can be considered a facilitator of mammography, as it increases the likelihood that the HCP will issue a referral to the woman. In this study, most of the women (29) had had an annual clinical breast examination by an HCP, and 19 had been referred for mammograms by these HCPs within the previous year. In addition, having mammogram equipment that can be lowered to accommodate women who are unable to stand may positively affect whether a woman will continue to adhere to a regular mammogram schedule. For example, two women in the study, both wheelchair users, reported no barriers in getting mammograms because the equipment accommodated their disability and the staff was supportive and helpful to them during the procedure. One woman who used a wheelchair reported being able to “stay in your wheelchair and they lower that thing and they twist it and turn it and all those kinds of stuff.” The same woman commented that “. . . they (the staff) were very friendly and told me what they were doing and why they were doing what and all that. So it was good.”

Annual reminders through letters, cards, or phone calls from breast centers and/or doctors' offices can improve the rate of mammography use.3 In this study, five women reported getting an annual reminder from their physician's office or the screening facility.

Discussion

This was a study of the perceived barriers and facilitators related to breast cancer screening from the perspective of 36 women with MS. A qualitative descriptive design was used to analyze data from the interviews to obtain a comprehensive summary of the barriers and facilitators in the everyday language of the women.14 Although most (70%) of the women in this study reported participating in breast cancer screening, some of the women expressed concerns about the obstacles they faced in the process. Barriers to obtaining mammograms were reported by a majority of the women with mobility impairments. Increasing participation in breast cancer screening among women with MS depends on removing those environmental and intrapersonal barriers.

The environmental barriers to mammography reported by the women in this study included transportation issues, inaccessibility within the facility, difficulty with positioning in the mammogram machine, and barriers related to HCPs, such as negative attitudes and a lack of referrals. These findings are consistent with the results of earlier research in which women with disabilities described obstacles to mammography screening.10–13

The intrapersonal barriers to screening expressed by the women included lack of time, lack of knowledge, lack of perceived susceptibility, pain or discomfort, and no más (having enough to deal with). Specific to BSE, women discussed having difficulty with remembering, self-efficacy, and fear and denial. There is a paucity of research on intrapersonal factors that influence breast cancer screening behavior specifically in this population. Previous research, however, by Becker and Stuifbergen18 suggests that fatigue is a major barrier to carrying out activities of daily living among women with MS. In this study only one woman reported fatigue to be an obstacle to screening. Although their findings are not specific to breast cancer screening, Stuifbergen et al.19 provide evidence that one of the variables predicting health-promoting behaviors among individuals with chronic disabling conditions such as MS is self-efficacy. Likewise, in studies on breast cancer screening among the general population as well as among racial/ethnic minority groups, self-efficacy and perceived susceptibility are predictive of BSE and mammography.4 20 The findings of this study regarding both self-efficacy and perceived susceptibility suggest a relationship between these variables and participation in screening, supporting earlier studies.

The intrapersonal barrier no más, or the concept of already having enough to deal with, reported by some of the women in this study has not been previously emphasized in published literature. Understandably, some women with MS cannot fathom having to deal with the demands of yet another illness such as breast cancer. The scenario of having two chronic illnesses simultaneously is complicated by the uncertainty that accompanies both MS and breast cancer. No más may be a barrier associated with negative coping strategies that is characterized by avoidance of the behavior, in this case breast cancer screening. Taylor et al.21 refer to this type of coping strategy as “disengaged,” which is a coping style that precipitates avoidant behavior. As with other barriers described by these women, the concept of no más highlights the need for health-care professionals to understand the stressors faced by women with chronic disabling conditions. The accumulation of such stressors can be an obstacle to many health-promoting behaviors, including breast cancer screening.

Although most of the women who did not obtain mammograms in the last year had mobility impairments and reported having barriers to mammography, 9 of the 17 women with mobility impairments reported having had a positive screening experience as a result of accommodating equipment and helpful technicians. In addition to these facilitators, women indicated that their breast centers and physicians' offices provided annual reminders (ie, cards, phone calls, letters). All of the women who received annual mammograms had been referred by their HCP and/or received annual reminders. These findings are consistent with prior research findings for the general population, showing that mammography adherence is strongly correlated with having a healthcare referral or annual reminders.3

Recently, there has been much discussion regarding the frequency, appropriate age, and usefulness of breast cancer screening (mammography and BSE). These controversial, emotionally charged changes in the guidelines have been a source of some public confusion. Given the higher risk for breast cancer in the MS population combined with the cumulative barriers these women face in obtaining screening, it seems particularly important for HCPs to educate these women about the benefits and risks related to mammography and BSE so that women can make informed choices.

The limitations of this study are related to the fact that the sample was chosen from a group of women participating in an ongoing longitudinal study on health promotion in people with MS. As such, they may be especially motivated with respect to health-promoting behaviors. Therefore, the findings may not be representative of the experiences of the general population of women with MS. In addition, this was a well-educated sample of women with MS; in the general population, higher education is related to a greater frequency of health promoting and screening behaviors. Thus, a broader sample of women with MS might report a lower frequency of mammography and greater barriers.

Despite the limitations, this study has provided valuable information for future studies in this area. Specifically, we have gained a clearer understanding of the barriers that influence breast cancer screening use among women with chronic disabling conditions such as MS. Furthermore, this information will be helpful for developing or modifying an instrument specific to women with disability that measures barriers to as well as benefits and facilitators of breast cancer screening. Future research could include quantitative studies using these targeted instruments to predict determinants of breast cancer screening behavior in this population. In addition, the concept of no más as a barrier to breast cancer screening and other health-promoting behaviors warrants further investigation, as this phenomenon may have important implications for HCPs caring for women with chronic disabling conditions such as MS.

Practice Points

Women with MS, especially those with mobility impairments, face environmental and intrapersonal barriers to breast cancer screening. Such women may be resistant to screening because they feel that they “already have enough to deal with” in managing their MS and doubt their ability to face a possible additional diagnosis of breast cancer.

Facilitators of breast cancer screening include annual reminders, referrals by health-care providers, and technicians who are knowledgeable about and sensitive to the needs of women with mobility impairments.

Health-care providers can be instrumental in reducing barriers to breast cancer screening by understanding the obstacles these women face and taking steps to minimize them.

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2009. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/MED/content/downloads/MED_1_1xCTF2. Accessed April 1, 2010.

Tabar L, Yen M, Vitek B, Chen H, Smith H, Duffy S. Mammography service screening and mortality in breast cancer patients: 20 year follow-up before and after introduction to screening. Lancet. 2003; 361: 1405–1410.

Schueler K, Chu P, Smith-Bindman R. Factors associated with mammography utilization: a systematic quantitative review of the literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008; 17: 1477–1498.

Champion VL, Monahan PO, Springston JK, . Measuring mammography and breast cancer beliefs in African American women. J Health Psychol. 2008; 13: 827–837.

Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Siebens H. Mobility impairments and use of screening and preventive services. Am J Public Health. 2000; 90: 955–961.

Chevarley FM, Thierry JM, Gill CJ, Ryerson AB, Nosek MA. Health preventive care and health care access among women with disabilities in the 1994–1995 National Health Interview Survey, Supplement on Disability. Womens Health Issues. 2006; 16: 297–312.

Wei W, Findley PA, Sambamoorthi U. Disability and receipt of clinical preventive services among women. Womens Health Issues. 2006; 16: 286–296.

Roetzheim R, Chirikos T. Breast cancer detection and outcomes in a disability beneficiary population. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2002; 13: 461–476.

Nielson N, Rostgaard K, Rasmussen S, . Cancer risk among patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J Cancer. 2006; 118: 979–984.

Becker H, Stuifbergen A, Tinkle M. Reproductive health care experiences of women with disabilities: a qualitative study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(12 suppl 5):S26–S33.

Smeltzer S, Sharts-Hopko N, Ott B, Zimmerman V, Duffin J. Perspectives of women with disabilities on reaching those who are hard to reach. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007; 39: 163–171.

Barr JK, Giannotti TE, Van Hoof TJ, Mongoven J, Curry M. Understanding barriers to participation in mammography by women with disabilities. Am J Health Promot. 2008; 22: 381–386.

Liu S, Clark M. Breast and cervical cancer screening practices among disabled women aged 40–75: does quality of experience matter? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17:1321–1329.

Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340.

Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985.

Graneheim U, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004; 24: 105–112.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982; 37: 122–147.

Becker H, Stuifbergen A. What makes it so hard? barriers to health promotion experienced by people with multiple sclerosis and polio. Fam Community Health. 2004; 27: 75–85.

Stuifbergen AK, Seraphine A, Roberts G. An explanatory model of health promotion and quality of life in chronic disabling conditions. Nurs Res. 2000; 49: 122–129.

Champion V, Menon U. Predicting mammography and breast self-examination in African American women. Cancer Nurs. 1997; 20: 315–322.

Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Aspinwall LG, Schneider SG, Rodriguez R, Herbert M. Optimism, coping, psychological distress, and high-risk sexual behavior among men at risk for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992; 63: 460–473.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by Grant R01NR003195-14S, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health.