Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

A Systematic Review of Stress-Management Interventions for Multiple Sclerosis Patients

Author(s):

Background: The objective of this study was to identify stress-management interventions used for people with multiple sclerosis (MS) and systematically evaluate the efficacy of these interventions.

Methods: Several strategies were used to search for studies reported in articles published up to 2013.

Results: Our initial search retrieved 117 publications, of which 8 met our criteria for review. Of the eight studies, one provided Class I evidence, five provided Class III evidence, and two provided Class IV evidence for the efficacy of stress-management interventions according to the evidence classification established by the American Academy of Neurology. Most studies showed positive changes in outcomes assessed; however, the range of methodological quality among the published studies made it difficult to draw conclusions.

Conclusions: The promising findings for stress-management interventions highlight the need for future studies. Additional large, prospective, multicenter studies will help to define the role of stress-management interventions in the treatment and course of MS. Furthermore, including outcome measures based on biological and clinical markers of disease will prove useful in understanding potential underlying mechanisms.

Throughout the course of history, scientists have recognized the impact of stress on chronic illness. From the time multiple sclerosis (MS) was first identified, psychological factors such as stress were among the first symptoms associated with the disease. Jean Martin Charcot, who first identified MS in the 19th century, wrote that grief, vexation, and adverse events in one's social situation were closely related to its onset.1

In the 1930s, Hans Selye presented the initial concept of the stress response, which continues to guide our conceptualization today. Selye defined the stress response as “the nonspecific response of the body to any demand, whether it is caused by, or results in, pleasant or unpleasant conditions.”2 He also acknowledgedbiological and psychological bases for how the body responds to a given stressor.2 3 From a psychological perspective, Selye recognized that the stress response could be mobilized not only in response to a stressor, but also in anticipation of a stressor. Thus, our psychological state can also negatively affect physical disease processes.2

There is a growing body of literature examining stress-management interventions for people with MS, although there has not been a systematic review addressing these findings. Prior reviews have been conducted on the topic of stress and MS, but they are descriptive in nature: they summarize the literature on mechanisms linking stress to MS, but do not review intervention studies. Systematic reviews have been conducted on related interventions, such as self-management (eg, Plow et al.,4 Rae-Grant et al.5); however, none have focused solely on stress management. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to review and evaluate the efficacy of stress-management interventions for people with MS.

Methods

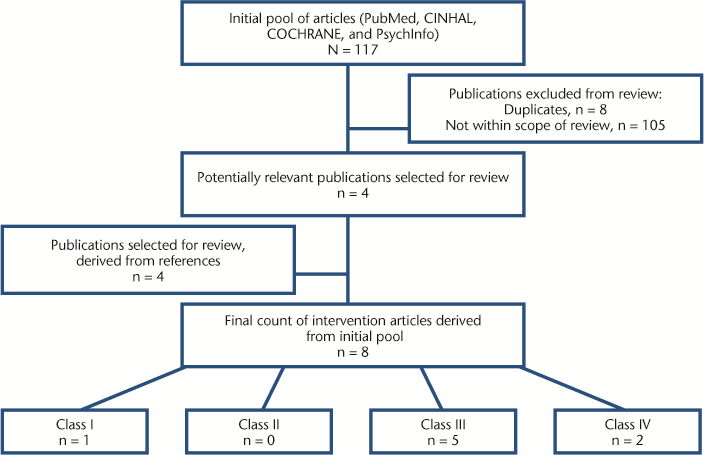

Searches were conducted in databases including PubMed, CINHAL (EBSCO Publishing, Glendale, CA), COCHRANE, and PsychInfo through February 2013 to identify articles that reported on stress-management interventions for people with MS. Stress-management interventions were defined as psychological techniques employed to support MS patients in reducing emotional or physiological responses resulting from stressful events (including stress related to the disease process). The headings “multiple sclerosis” and “stress, psychological” were used in addition to the following subheadings: “psychology,” “therapy,” and “prevention and control.” Articles included were published in peer-reviewed journals in the English language. Cited references to full-text articles were also reviewed to identify additional intervention studies. The following criteria had to be met for inclusion in the systematic review: a) the intervention included techniques to decrease stress or improve management thereof, and b) the study's sample consisted in part or entirely of individuals with MS. A diagram of the literature retrieval process and breakdown by classification is shown in Figure 1. Most of the articles in the initial pool of publications were reviews or case reports or did not meet our search criteria.

CONSORT diagram of the literature retrieval process and breakdown by classification

The articles were screened independently by the first and second authors (AKR, ABS). The last author (ARG) assisted in determining the final list of articles based on the inclusion criteria. Articles included in the review were classified according to the criteria of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Committees.6 The first and second authors (AKR, ABS) classified the articles independently, and a final set of ratings was adjudicated by the last author (ARG).

Results

Our search yielded a total of 117 publications. Four publications met the criteria for inclusion, and four full-text publications were derived from the references of the initial pool of articles. Thus, eight publications were included in the present review (Table 1).7–14 The majority of studies (n = 7) were uncontrolled, with subjective outcome measures.8–14 Only one study met AAN criteria for Class I,7 and the remainder met criteria for Class III (n = 5)8–12 and Class IV (n = 2).13 14

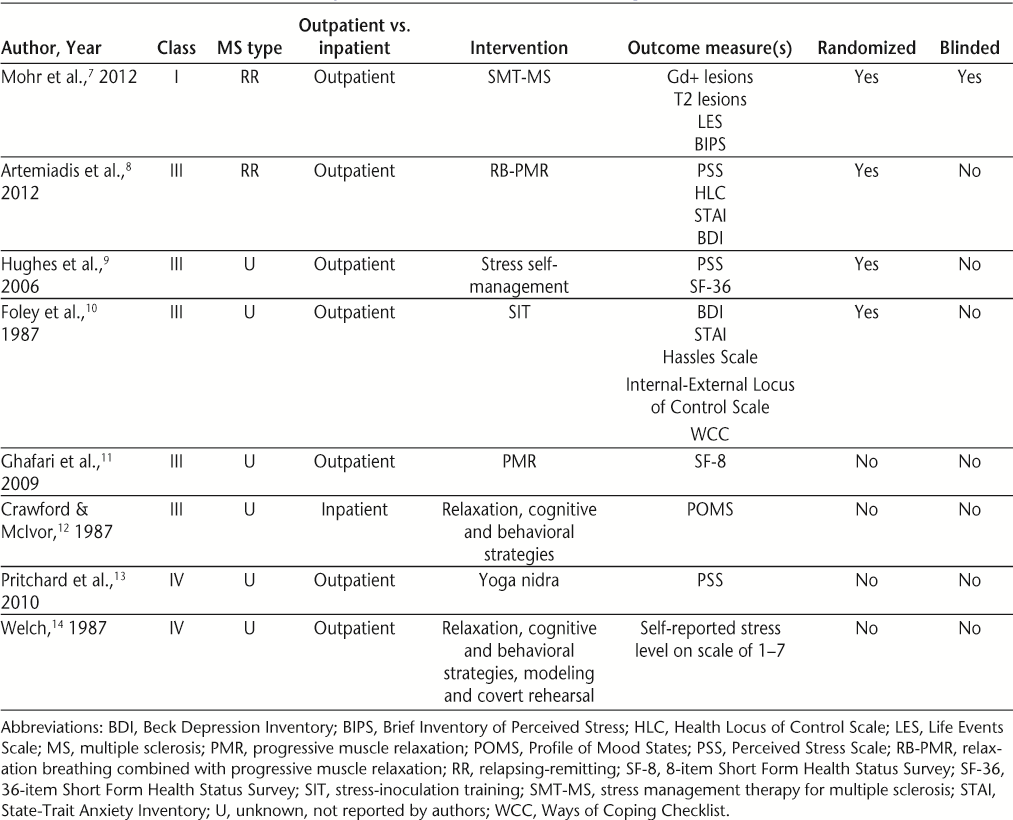

Studies of stress-management interventions for MS patients

Characteristics of Study Samples

Research samples ranged in size from 7 to 121 participants. The mean age of patients studied was approximately 41.4 years. Most studies included outpatients with MS, with the exception of one study that used an inpatient sample.12 Only two of the eight publications reported on the MS classification of their sample (ie, relapsing-remitting).7 8 There was great variability with respect to quantifying MS disability impairment, which ranged from description of mobility level14 to patient score on measures of disability9 or clinician rating of disability.7 8 10–12 One study did not report disability level of the sample.13

Interventions

Cognitive-behavioral techniques including self-monitoring of daily stress, cognitive restructuring, and problem-solving were reported in five of the eight publications meeting the inclusion criteria.7 9–12 The majority of studies included some form of relaxation training (frequently used with cognitive-behavioral strategies). The most common relaxation techniques were abdominal breathing and progressive muscle relaxation, although such strategies were used as the sole form of therapy in just two studies.8 11 One study used a meditation technique as the intervention.13 While many of the stress-management therapies in the included studies are similar, no two studies used the exact same intervention. The average length of intervention was 9.5 weeks (range, 5–24 weeks).

Outcomes Measured

A variety of measures were used to assess the efficacy of stress-management interventions in the included articles (Table 1). The most commonly employed tools assessed perceived levels of stress (n = 5), and consisted of validated, self-report questionnaires measuring the occurrence of negative stressful events or subjective perception of stress.7–10 13 One study utilized a 7-point stress rating scale that has not yet been validated.14

Outcome measures evaluating other psychological symptoms were also used in many of the studies. Quality of life was used as an outcome variable in two studies,9 11 but was used as the sole outcome measure in just one study.11 Additional measures in the included studies covered a variety of domains including depression,8–10 anxiety,8 10 locus of control,8 10 coping,10 disability status,10 and self-rating of MS symptom intensity.8 The study conducted by Mohr et al.7 was the only one that used a biological outcome measure as an endpoint.

Stress-Management Class I Evidence

The trial by Mohr and colleagues7 is the only study conducted to date providing Class I evidence that stress-management therapy affects the MS disease process. The authors performed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a manualized stress-management therapy program based on cognitive-behavioral therapy.15 The intervention took place over 24 weeks and consisted of 16 individual, face-to-face sessions lasting approximately 50 minutes each. One hundred twenty-one individuals with relapsing-remitting MS participated and were randomly assigned to the treatment group (n = 60) or a wait-list control group (n = 61). Compared with participants in the control group, treated participants developed fewer new gadolinium-enhancing (Gd+) and T2 brain lesions and remained free of Gd+ and T2 lesions up to 24 weeks. No significant differences between groups were found beyond 24 weeks.

This study provided Class I evidence owing to the following factors: The study was an RCT with an objective outcome assessment (ie, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] brain lesions). Clinical evaluators and technicians were blinded to treatment assignment. The primary outcome variable was specified (ie, cumulative number of Gd+ lesions during the active treatment period), there were clearly defined exclusion/inclusion criteria, the study accounted for dropouts, and it was noted that the lost-to-follow-up rate did not differ significantly across treatment groups.

Stress-Management Class III Evidence

Artemiadis et al.8 conducted an unblinded RCT of relaxation training for stress management in relapsing-remitting MS patients. Sixty-one patients were randomized to a control condition (n = 30) or an 8-week stress-management program (n = 31), administered via a guided audio CD of relaxation breathing and progressive muscle relaxation. Participants were instructed to use the audio CD at home twice per day. Differences in favor of the intervention group were found for perceived stress and depression symptoms at 8 weeks.

A relaxation-based stress-management protocol was also conducted by Ghafari et al.,11 who used a quasi-experimental design to evaluate the effects of progressive muscle relaxation on health-related quality of life. Sixty-six participants with MS (33 per group) were matched on variables of interest. Participants in the intervention arm performed progressive muscle relaxation at home using an instructional audio CD once per day. Quality of life scores (using the 8-item Short Form Health Status Survey; SF-8) improved significantly for individuals in the intervention group compared with the control group.

Hughes et al.9 undertook a 6-week group stress self-management intervention for women with disabilities including spinal cord injury, MS, and arthritis. Seventy-eight women were randomly assigned to a wait-list control group or the intervention, which consisted of psychoeducation on the topic of stress, time-management strategies, pain-management strategies, relaxation training, social support and relationship issues, and physical self-care. Group differences were found at the 3-month follow-up; women who participated in the intervention demonstrated significantly lower scores on measures of perceived stress and mental health aspects of quality of life (36-item Short Form Health Status Survey; SF-36).

Crawford and McIvor12 evaluated the efficacy of a stress-management intervention for hospitalized MS patients using a nonrandomized, unblinded design, although the authors reported that groups were equivalent on variables of interest including age, length of illness, and degree of disability. Patients in the intervention condition participated in a 13-week group program consisting of relaxation and cognitive-behavioral techniques aimed at stress management. Differences favoring the intervention group were found with regard to depression, anxiety, and vigor.

A similar intervention was conducted by Foley et al.,10 who combined cognitive-behavioral techniques and progressive muscle relaxation. The authors created a six-session treatment protocol adapted for patients with MS. A wait-list control comparison group was also included in the study. Individuals who participated in the intervention demonstrated significant improvements on measures of depression, anxiety, and distress compared with the control group.

Stress-Management Class IV Evidence

Welch14 conducted a 5-week nonrandomized, uncontrolled stress-management intervention for seven MS patients. Patients were drawn from a convenience sample of subjects already participating in an ongoing MS self-help group. The intervention consisted of a variety of techniques typical of stress-management programs including daily self-monitoring of stress levels, relaxation training, and cognitive restructuring. A unique aspect of the intervention included modeling and covert rehearsal, which entailed role-play of a stress-provoking event and successfully coping with accompanying emotional responses. The sole outcome consisted of a stress rating scale, which has not yet been validated, in which participants rated stress levels on a scale of 1 (little/no stress) to 7 (great stress). Overall, participants reported significantly decreased levels of stress following completion of the study compared with baseline.

Pritchard et al.13 described a yoga nidra meditation program for reducing perceived stress levels in MS and cancer patients. A total of 22 individuals (10 cancer patients and 12 MS patients) were recruited for the study, and one class was held for each group of patients. Classes met once per week for 6 weeks. Both groups demonstrated significant reductions in perceived levels of stress. There was no significant difference by group (MS vs. cancer).

Discussion

The range of interventions and outcome measures in the studies reviewed made it difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the efficacy of stress-management interventions for people with MS. Furthermore, methodological rigor as well as the quality of methodology varied significantly among the studies. Half of the studies were nonrandomized, and only one study was blinded. The majority of studies meeting Class III evidence were not blinded, and studies meeting Class IV evidence were not randomized or blinded. However, given the nature of psychological interventions, blinding and double-blinding are particularly challenging and at times unfeasible.

Objective assessment of MS disease activity has been underutilized in the studies conducted to date, likely because of the increased cost and personnel often required to obtain such measures. Outcome measures have been largely limited to patient report, as opposed to objective assessments including laboratory markers and/or clinical outcomes.

In addition, many of the trials have not followed patients over the long term. Such follow-up is needed to ascertain the impact of interventions over time, particularly in light of the Mohr et al.7 trial, which failed to show differences between the treatment and control groups with respect to new Gd+ and T2 brain lesions beyond 24 weeks. It is also important to know whether patients continue using the intervention skills beyond study participation and how this relates to the ability to maintain the gains observed during the intervention. Finally, despite the Class I rating assigned to the study conducted by Mohr and colleagues,7 additional confirmatory studies of MRI measures are likely warranted.

Future researchers may want to emulate a strong prospective stress-management intervention study that examined the effect of a cognitive-behavioral stress-management intervention on serum cortisol and relaxation during treatment for nonmetastatic breast cancer. In this study by Phillips et al.,16 the authors included 128 participants who were randomly assigned to either a 10-week cognitive-behavioral stress-management group or a 1-day psychoeducation seminar control group. Outcome measures included serum cortisol level and a relaxation measure. Participants receiving the stress-management intervention had significantly lower cortisol levels and improved perception of relaxation ability than those in the control group. A similar protocol could be developed that would include prospective, randomized, controlled methods to examine stress response as measured with biomarkers (eg, serum cortisol) in MS patients.

Conclusion

There is significant variation among the reviewed studies, primarily centering on type of stress-management interventions conducted, methodological rigor, and outcome measures assessed. Given these limitations, the results appear promising, as most studies demonstrated improvements in patient-reported outcome measures. Also important, the study that had the highest level of quality according to AAN criteria showed significant changes with respect to MRI brain lesions and patient report of stress via validated questionnaires.

Large, prospective, multicenter trials will help to further define the role of stress-management interventions in the treatment and course of MS. Additional research is also needed to establish a benefit of stress-management interventions beyond patient-reported outcomes, including biological and clinical measures.

PracticePoints

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is the most frequently used stress-management intervention in trials conducted to date.

Stress-management interventions may help people with MS reduce perceived stress, improve quality of life, reduce mental health comorbidities, and improve outcomes associated with the disease.

Including outcome measures based on biological and clinical markers of disease could prove useful in understanding potential underlying mechanisms of stress-management interventions for MS patients.

References

Charcot JM. Lectures on Diseases of the Nervous System. Sigerson G, trans. London: New Sydenham Society; 1877.

Selye H. The Stress of My Life. New York, NY: Van Nostrand; 1979.

Selye H. The general adaptation syndrome and the diseases of the adaptation. J Clin Endocrinol. 1946; 6: 117–231.

Plow MA, Finlayson M, Rezac M. A scoping review of self-management interventions for adults with multiple sclerosis. PM R. 2011; 3: 251–262.

Rae-Grant AD, Turner AP, Sloan A, Miller D, Hunziker J, Haselkorn JK. Self-management in neurological disorders: systematic review of the literature and potential interventions in multiple sclerosis care. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011; 48: 1087–1100.

Edlund W, Gronseth G, So Y, Franklin G. Clinical Practice Guideline Process Manual. St. Paul, MN: American Academy of Neurology; 2004.

Mohr DC, Lovera J, Brown T, et al. A randomized trial of stress management for the prevention of new brain lesions in MS. Neurology. 2012; 79: 412–419.

Artemiadis AK, Vervainioti AA, Alexopoulos EC, Rombos A, Anagnostouli MC, Darviri C. Stress management and multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2012; 27: 406–416.

Hughes RB, Robinson-Whelen S, Taylor HB, Hall JW. Stress self-management: an intervention for women with physical disabilities. Womens Health Issues. 2006; 16: 389–399.

Foley FW, Bedell JR, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC, Reznikoff M. Efficacy of stress-inoculation training in coping with multiple sclerosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987; 55: 919–922.

Ghafari S, Ahmadi F, Nabavi M, Anoshirvan K, Memarian R, Rafatbakhsh M. Effectiveness of applying progressive muscle relaxation technique on quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Nurs. 2009; 18: 2171–2179.

Crawford JD, McIvor GP. Stress management for multiple sclerosis patients. Psychol Rep. 1987; 61: 423–429.

Pritchard M, Elison-Bowers P, Birdsall B. Impact of integrative restoration (iRest) meditation on perceived stress levels in multiple sclerosis and cancer outpatients. Stress and Health. 2010; 26: 233–237.

Welch GJ. Social work intervention with a multiple sclerosis population. Br J Social Work. 1987; 17: 45–59.

Mohr DC. The Stress and Mood Management Program for Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis: Therapist Guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Phillips KM, Antoni MH, Lechner SC, et al. Stress management intervention reduces serum cortisol and increases relaxation during treatment for nonmetastatic breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 2008; 70: 1044–1049.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.