Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Using Objective and Subjective Measures of Cognition to Predict Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Abilities in Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

Cognitive impairment, difficulty performing basic activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental ADLs (IADLs), depression, and fatigue are common among individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS). Some associations between these symptoms are known; however, many of their relationships remain unclear. This study investigated the contributions of subjective and objective cognition, depressive symptom severity, and fatigue on ADLs and IADLs.

METHODS:

Participants (N = 217) were individuals with MS from a comprehensive MS center, participating in a larger study characterizing upper extremity function in MS. Outcome measures of ADL and IADL abilities were the Functional Status Index-Assistance (FSI-A) and Functional Status Index-Difficulty (FSI-D) and the Test D’évaluation Des Membres Supérieurs de Personnes Âgées (TEMPA). Predictors were objective cognition (Symbol Digit Modalities Test; SDMT), subjective cognition (Performance Scales©-Cognition; PS-C), depressive symptom severity (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CES-D-10), and fatigue (Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; MFIS-5). Correlations were conducted, followed by hierarchal linear regressions. The SDMT and PS-C were entered into separate models.

RESULTS:

After controlling for demographics, the SDMT significantly predicted the TEMPA and FSI-A, while the PS-C predicted only the FSI-D. The CES-D-10 predicted the FSI-D even after accounting for PS-C and SDMT, while the MFIS-5 only predicted the FSI-D when the SDMT was included. Neither the CES-D-10 nor MFIS-5 significantly predicted the FSI-A or TEMPA.

CONCLUSIONS:

The way an individual with MS perceived their symptoms significantly contributed to their reported difficulty with functional tasks, while only their objective cognitive functioning predicted ADL and IADL performance and the level of assistance they would require.

Many individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) struggle with basic activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental ADLs (IADLs), which are essential to independent living.1 One contributing factor is their cognitive functioning. In addition to being the most common deficit in MS,2 slowed processing speed has been associated with difficulty in performing IADLs3,4 and reduced participation in social, household, and productive (ie, employment and educational) activities.5,6 However, the relationship between objective assessment of IADLs and self-reported cognition among individuals with MS has yet to be explored. While self-reported cognition has not been found to be associated with objective cognitive impairment,7 there is evidence to suggest that self-reported cognition is related to perceived functional ability.1 For instance, individuals with MS who provide more negative self-assessments of their cognitive function tend to perceive more IADL deficits.1 In addition to cognition, fatigue and depression can contribute to self-reported IADL disabilities. Research has shown that fatigue can lead to worsened general health perception, increased depressive symptoms, and decreased physical function, which leads to more self-reported dysfunction in conducting daily activities for individuals with MS.8 In addition, depressive symptom severity is negatively associated with participation in outdoor and leisure activities.6

Improving the understanding of how different constructs of cognition, depression, and fatigue are related to objective and subjective measurements of ADL and IADL abilities may help to inform assessment needs when individuals with MS present with functional difficulties. For example, if a patient reports needing more assistance to complete their daily tasks, this may prompt an objective assessment of their processing speed or further investigation into their fatigue symptoms as part of their workup. As such, this study examines the contributions of subjective and objective cognitive functioning, depressive symptom severity, and fatigue on different measurements of ADL and IADL abilities among individuals with MS. Our hypothesis is that processing speed will be predictive of task completion time, while self-reported cognitive functioning will have a greater influence on perceived functional abilities. Furthermore, the levels of depression and fatigue reported by individuals with MS will contribute to subjective, but not objective, measurement of ADL and IADL abilities.

METHODS

Participants

This study utilized data from a larger study that created the MS Characterization of the Upper Extremity (MS-CUE) database using a random sample of individuals with MS.9 The study procedures were approved by the Trinity Health Of New England Institutional Review Board. Participants were receiving routine care at the Joyce D. and Andrew J. Mandell Center for Comprehensive Multiple Sclerosis Care and Neuroscience Research (Mandell Center), a comprehensive MS center in Hartford, Connecticut. Individuals were eligible if they had a clinical diagnosis of MS; a score of 22 or greater on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), spoke English, and were 18 years of age or older. Those who were unwilling or unable to complete assessments, had acute upper limb injuries or other comorbidities that currently and directly influenced either their upper limb or hand function, and/or had a relapse less than 2 months prior to enrollment were excluded. From the 267 individuals in the dataset, 217 were selected for inclusion in the current study based on completion of the 4 predictor measures and 3 outcome measures, as described below.

Measures

Demographic and Disease-Related Characteristics

The demographic and disease-related variables collected and examined as possible covariates included age, level of education (≤ 12 years or > 12 years), employment status (employed or unemployed), disability (measured using the Patient-Determined Disease Steps; PDDS),7,10-12 disease duration (in years), ethnicity, and race. Visual impairment was examined bilaterally; level of impairment (mild to none or moderate to severe)13 was determined using the Snellen chart due to its potential to act as a confounder in assessments of ADL and IADL abilities in individuals with MS.3 Pain severity over the past month (Visual Analog Scale-Pain; VAS-P)14 was also included, as pain fluctuations can contribute to levels of physical and social function.15

Outcome Measures

The Test D’évaluation Des Membres Supérieurs de Personnes Âgées (TEMPA) is a standardized upper extremity (UE) function assessment, consisting of 9 timed and rated tasks. The 5 bilateral tasks are to open a jar and take a spoonful of coffee, to unlock a lock and open a pill container, to write on an envelope and stick on a stamp, to tie a scarf, and to shuffle and deal playing cards. The 4 unilateral tasks are to pick up and move a jar, to pick up a pitcher and pour water into a glass, to handle coins, and to pick up and move small objects.16,17 In the current study, the total time taken to complete all 9 TEMPA tasks (in seconds) was used as an objective measure of ADL and IADL ability.

The Functional Status Index (FSI) is an 18-item self-report questionnaire that assesses 5 general categories of ADLs and IADLs: mobility, personal care, home chores, hand activities, and social/role activities. Each item is rated on a 4- to 5-point scale for amount of assistance required (FSI-A), level of difficulty (FSI-D), and amount of pain experienced (FSI-P) while performing that activity. For this study, only the average scores of the FSI-A and FSI-D were included as the subjective measures of ADL and IADL ability. Higher scores indicate more assistance needed or more difficulty when performing the activity.18 For the FSI-A, the participant rates the level of assistance they recall needing, on average, over the past 7 days; for the FSI-D, the participant rates the level of difficulty they experienced when performing these same activities. If a participant did not complete an activity during this time frame, it is omitted in both sections.18 The internal consistency (a) was 0.94 for the FSI-A and 0.87 for the FSI-A in the current sample.

Predictor Measures

The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) is an objective and valid measure of information processing speed, in which the participant matches the corresponding number to a series of symbols.19 The number of correct answers given in 90 seconds are totaled and then transformed into z-scores using published normative data, with lower z-scores indicating greater impairment.19 Because the original study's goal was to characterize the contribution of UE dysfunction in the overall functioning of individuals with MS, the majority of participants (97.2%) completed the written version of the SDMT. Participants who could not complete the handwritten test due to tremor, weakness, or any other symptoms that might prevent it (2.8%) were instead given the oral version to complete.

The Performance Scales© 1993 DeltaQuest (TXu000743629) is a self-report measure for MS-associated disability that assesses an individual's mobility, bowel/bladder function, fatigue, sensory deficits, vision, cognition, spasticity, and hand function.20,21 The cognitive item (PS-C) was the current study's measure of self-reported cognitive functioning, in which the participant rated the severity of their cognitive difficulties within the past month on a scale of 0 (normal cognition) to 5 (total cognitive disability). The PS-C has been shown to correlate with other subjective measures of cognition such as the Perceived Deficits Questionnaire.7

The 5-item version of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS-5) was used to evaluate self-reported fatigue.22 A valid measure of fatigue in MS, the MFIS-5 measures the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial impact of fatigue over the past 4 weeks.22 For each item, the participant rates their agreement on a scale of 0 (never) to 4 (almost always), with the final score being the sum of all 5 items. In the current sample, the MFIS-5 had an internal consistency of 0.91.

Depressive symptom severity was assessed with the 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10), which has been validated in MS.23 The participant rates how often they experienced a symptom within the past week, ranging from less than 1 day to 5 to 7 days. The total CES-D-10 scores ranged from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating increased severity of depressive symptoms.24 The CES-D-10 had an internal consistency of 0.85 in the current sample.

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate analyses were conducted to assess whether the selected demographic, disease-related, cognitive, depressive symptom severity, and fatigue measures were associated with ADL and IADL ability. Spearman correlations were used for ordinal and interval variables, while Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for categorical variables, as the outcome variances were non-normally distributed. Only variables significant in the bivariate analyses (P < .05) were included in the multivariate analyses. Hierarchical ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regressions were then conducted, with covariates in the first step, cognition in the second step, depressive symptom severity in the third step, and fatigue in the final step. The SDMT and PS-C, with 0 (normal cognition) as the reference for the latter variable, were entered into separate models in order to investigate their individual contributions to ADL and IADL ability. Homoscedasticity and linearity were assessed visually with scatterplots, while multicollinearity, independence of errors, and normal distribution of the residuals were evaluated with variance inflation factor and tolerance statistics, a Durbin-Watson test, and a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of the residuals, respectively. With the exception of the FSI-A model with the SDMT, the regressions were bootstrapped using 1000 samples due to non-normal residuals,25 with adjusted P values reported. All other assumptions were met, and the models were good fits for the data. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp).

RESULTS

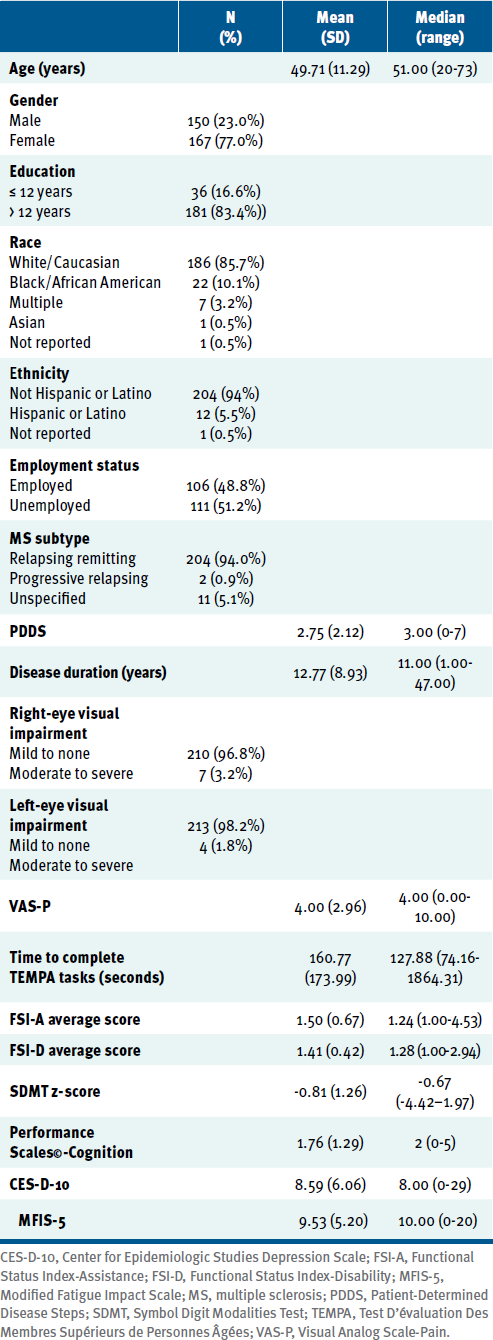

Participants (TABLE 1) were predominantly White (85.7%) and women (77.0%), with more than 12 years of education (83.4%). The median score on the PDDS was 3, which represents gait disability. On average, participants had a z-score of -0.81 ± 1.26 on the SDMT and a median rating of 2 on the PS-C, representing mild cognitive disability. Participants had a median score of 8.00 on the CES-D-10 and 10.00 on the MFIS-5. Their median performances on the TEMPA, FSI-A, and FSI-D were 127.88 seconds, 1.24 (ie, between being independent and using devices), and 1.28 (ie, between none and mild difficulty), respectively.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants (N = 217)

TEMPA

The TEMPA was significantly related to age (ρ = .43, P < .001), employment (U = 9533.00, P < .001), disability (ρ = .63, P < .001), disease duration (ρ = .28, P < .001), pain severity (ρ = .18, P = .009), and right-eye visual impairment (U = 1084.00, P = .033).

After controlling for these significant demographics, the SDMT was a significant predictor (ρ = –0.26, P = .045; TABLE S1), accounting for 5% of the model's variance. After adding the CES-D-10 in Step 3 and the MFIS-5 in Step 4, both of which were insignificant, the SDMT remained a significant predictor of the time taken to complete the TEMPA (ρ = –0.27, P = .050). Overall, the model accounted for 25% of the TEMPA's variance.

The PS-C was not included in the regression analyses because it was not significantly associated with the TEMPA (ρ = .12, P = .091).

FSI-A

The FSI-A was significantly related to age (ρ = .36, P < .001), employment (U = 9726.00, P < .001), disability (ρ = .80, P < .001), disease duration (ρ = .26,P < .001), pain severity (ρ = .33, P < .001), and right-eye visual impairment (U = 1168.50, P = .007).

After controlling for the significant demographics, the SDMT was also a significant predictor ρ = -0.17, P < .001; TABLE S2), accounting for 2% of the model's variance. It remained a significant contributor even after the addition of the CES-D-10 in Step 3 and MFIS-5 in Step 4 (ρ = -0.17, P < .001). Neither the CES-D-10 nor the MFIS-5 was significant in this model. Overall, the model accounted for 64% of the FSI-A's variance.

The PS-C was not a significant predictor of the FSI-A (TABLE S3),nor were the CES-D-10 or MFIS-5 when added to the model. The overall model accounted for 63% of the FSI-A's variance.

FSI-D

The FSI-D was significantly associated with age (ρ = .28, P < .001), employment (U = 8687.00, P < .001), disability (ρ = .68, P < .001), disease duration (ρ = .20, P = .003), pain severity (ρ = .43, P < .001), and ethnicity (U = 1645.00, P = .045).

The SDMT was not a significant predictor of the FSI-D (TABLE S4). However, the CES-D-10 was significant (ρ = 0.02, P = .001) and accounted for 5% of the model's variance. The CES-D-10 remained significant (ρ = 0.01, P = .025) with the inclusion of the MFIS-5 in Step 4, the latter of which was also significant (ρ = 0.02, P = .019), accounting for 2% of the variance. Overall, the model accounted for 52% of the FSI-D's variance.

On the other hand, the PS-C was a significant predictor of the FSI-D after controlling for demographics (TABLE S5), specifically mild cognitive disability (rating of “2”; ρ = 0.13, P = .010), moderate cognitive disability (rating of “3”; ρ = 0.15, P = .016), and severe cognitive disability (rating of “4”; ρ = 0.28, P = .002), accounting for 7% of the model's variance. Severe cognitive disability on the PS-C remained a significant contributor even after the addition of the CES-D-10 in Step 3 and the MFIS-5 in Step 4 (ρ = 0.18, P = .029). The CES-D-10, but not the MFIS-5, was significant in this model (ρ = 0.16, P = .043), accounting for 2% of the variance. The overall model accounted for 54% of the FSI-D's variance.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the contributions of subjective (PS-C) and objective (SDMT) cognitive functioning, depressive symptom severity (CES-D-10), and fatigue (MFIS-5) on measurements of ADL and IADL ability (TEMPA, FSI-A, FSI-D) among individuals with MS. As hypothesized, processing speed was a significant predictor of ADL and IADL completion time even after considering factors such as disability; neither depressive symptom severity nor fatigue significantly contributed to the model. This is consistent with previous findings that individuals with MS do not make additional errors on functional tasks, but, rather, that their performance deficits are due to processing speed deficits.3,4

While it was hypothesized that self-reported cognitive functioning would have a greater influence on perceived functional abilities, and that the levels of depression and fatigue felt by individuals with MS would contribute to subjective but not objective ADL and IADL abilities, divergence between the predictors of the FSI-A and FSI-D was unexpected. Consistent with the initial hypothesis, processing speed was not a predictor of perceived difficulty with ADLs and IADLs. However, it was a significant predictor of participants’ reported level of assistance. Furthermore, neither depressive symptom severity nor fatigue contributed to the amount of assistance participants reported that they needed to complete their ADLs and IADLs. While both the FSI-A and FSI-D are subjective measures of ADL and IADL abilities, these findings suggest that there may be different underlying phenomena contributing to the perceptions of individuals with MS. A future qualitative study may help elucidate how the cognitive function of an individual with MS plays a role in the amount of difficulty and assistance needed for ADL and IADL completion.

The observed relationships with the FSI-D are consistent with the hypothesis that perceived cognitive deficits would be related to the reported level of difficulty performing ADLs and IADLs, with depressive symptom severity and fatigue contributing to this perception. Even after accounting for depressive symptom severity and fatigue, having subjective severe cognitive disability (ie, endorsing constant problems with cognitive functioning) was a significant factor in the model. This may suggest that individuals with MS who report high levels of interference in their everyday lives due to cognitive problems are perceiving greater difficulties in completing their daily functional tasks, even when considering the contributions from their level of depression and fatigue.

In addition to improving the understanding of how cognition, depression, and fatigue contribute to different objective and subjective measures of ADL and IADL ability, these findings may help inform patient and provider conversations about what is at the root of their functional complaints. For instance, if an individual with MS reports that they are taking longer or they need greater assistance with daily tasks, evaluating their cognitive functioning with a brief and valid measure (eg, the SDMT) may reveal whether slowed processing speed is contributing to their ADL and IADL problems. In addition to educating the patient about how slowed processing speed can affect different areas of daily function, the findings from the brief cognitive assessment may prompt a referral for services, such as cognitive remediation.26 Similarly, assessing self-reported cognition, depressive symptom severity, and fatigue impact may be warranted if an individual endorses difficulty with their ADLs and IADLs, but they do not exhibit objective cognitive deficits. In addition to providing patients with greater insight into how their symptoms may be contributing to their daily functional difficulties, this may prompt referrals for pharmacological and nonpharmacological management (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy).27,28

When interpreting the results of the current study, a few limitations need to be considered. First, more than 97% of participants completed the written version of the SDMT. Because past studies suggest that UE motor deficits may cause slower writing times and thus lower scores,29 this may have artificially deflated the SDMT scores. In addition, as per the protocol of the original study, participants who could not complete the written SDMT due to tremor or weakness were allowed to complete the oral version. Therefore, those with intermediate disability, enough to deflate their scores but not enough to merit oral administration, would have been the most affected. Second, objective cognitive functioning was limited to performance on the SDMT. Although processing speed has been shown to be a significant contributing factor to IADL difficulties,3,4 other cognitive domains are associated with functional difficulties, including executive functioning and memory.3 Third, objective ADL and IADL assessments (ie, the TEMPA) may be misleading, given that the activities individuals with MS are capable of performing in a clinical setting may not align with their performances at home, where different factors are involved.30 In future studies, other factors associated with participation, such as self-efficacy and the importance of the activity,31 should be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

These results highlight that even after considering factors such as disability, an individual's perception of their MS symptoms (subjective cognitive functioning, depressive symptom severity, and fatigue) significantly contributes to their reported level of difficulty with ADLs and IADLs; objective cognitive functioning (processing speed) predicted completion time and level of assistance needed for these tasks. These findings elucidate the importance of cognition, depression, and fatigue on different aspects of functional ability and may help inform discussions between patients and providers about how the constellation of MS symptoms contributes to daily functioning, including possible referrals for interventions to help address these problems.

PRACTICE POINTS

Processing speed performance, but not self-reported symptoms, significantly contributes to quantitative time and subjective level of assistance that individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) need to complete functional tasks.

Subjective cognitive difficulties, depressive symptom severity, and fatigue were predictive of the amount of subjective difficulty that individuals with MS reported having with daily tasks.

Assessments of cognition, depression, and fatigue should be considered when individuals with MS endorse issues with their everyday activities, which may prompt referrals to address these problems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

The Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) is provided for use by the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry (https://www.narcoms.org/pdds). Permission was granted by Carolyn Schwartz, ScD, to publish data using the Performance Scales©-Cognition. The authors wish to thank Kayla Olson for her contribution to recruitment and data collection; Matthew Farr, Lindsay Neto, Carolyn St. Andre, and Nancy Rodriguez-Ocasio for their support and help in establishing reliability and training; the clinical team for their support of clinical research; and Mount Sinai Rehabilitation Hospital and the Mandell Center for Multiple Sclerosis for providing facilities and staff support for the study.

References

Fong MW, Lee E-J, Sheppard-Jones K, Bishop M. Home functioning profiles in people with multiple sclerosis and their relation to disease characteristics and psychosocial functioning. Work. 2015;52(4):767-776. doi:10.3233/WOR-152204

Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(12):1139-1151. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70259-X

Kalmar JH, Gaudino EA, Moore NB, Halper J, DeLuca J. The relationship between cognitive deficits and everyday functional activities in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology. 2008;22(4):442-449. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.442

Goverover Y, Genova HM, Hillary FG, DeLuca J. The relationship between neuropsychological measures and the Timed Instrumental Activities of Daily Living task in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13(5):636-644. doi:10.1177/1352458506072984

Cattaneo D, Lamers I, Bertoni R, Feys P, Jonsdottir J. Participation restriction in people with multiple sclerosis: prevalence and correlations with cognitive, walking, balance, and upper limb impairments. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(7):1308-1315. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2017.02.015

Ben Ari E, Johansson S, Ytterberg C, Bergström J, von Koch L. How are cognitive impairment, fatigue and signs of depression related to participation in daily life among persons with multiple sclerosis? Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(23):2012-2018. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.887797

Marrie RA, Goldman M. Validity of performance scales for disability assessment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13(9):1176-1182. doi:10.1177/1352458507078388

Bouchard V, Duquette P, Mayo NE. Path to illness intrusiveness: what symptoms affect the life of people living with multiple sclerosis? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(7):1357-1365. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2017.03.012

Pisa M, Ruiz JA, DeLuca GC, et al. Quantification of upper limb dysfunction in the activities of the daily living in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;63:103917. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2022.103917

Hohol M, Orav E, Weiner H. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a simple approach to evaluate disease progression. Neurology. 1995;45(2):251-255. doi:10.1212/wnl.45.2.251

Hohol M, Orav E, Weiner H. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study comparing disease steps and EDSS to evaluate disease progression. Mult Scler. 1999;5(5):349-354. doi:10.1177/135245859900500508

Learmonth YC, Motl RW, Sandroff BM, Pula JH, Cadavid D. Validation of Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) scale scores in persons with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:37. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-13-37

Dandona L, Dandona R. Revision of visual impairment definitions in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases. BMC Med. 2006;4:7 doi:10.1186/1741-7015-4-7

Downie WW, Leatham PA, Rhind VM, Wright V, Branco JA, Anderson JA. Studies with pain rating scales. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978;37(4):378-381. doi:10.1136/ard.37.4.378

Kratz AL, Braley TJ, Foxen-Craft E, Scott E, Murphy JF III, Murphy SL. How do pain, fatigue, depressive, and cognitive symptoms relate to well-being and social and physical functioning in the daily lives of individuals with multiple sclerosis? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(11):2160-2166. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2017.07.004

Feys P, Duportail M, Kos D, Van Aschand P, Ketelaer P. Validity of the TEMPA for the measurement of upper limb function in multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(2):166-173. doi:10.1191/0269215502cr471oa

Desrosiers J, Hébert R, Bravo G, Dutil É. Upper extremity performance test for the elderly (TEMPA): normative data and correlates with sensorimotor parameters. Test D’évaluation Des Membres Supérieurs de Personnes Âgées. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(12):1125-1129. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80120-0

Jette AM. Functional Status Index: reliability of a chronic disease evaluation instrument. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1980;61(9):395-401.

Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test: Manual. Western Psychological Services; 1982.

Schwartz CE, Vollmer T, Lee H. Reliability and validity of two self-report measures of impairment and disability for MS. North American Research Consortium on Multiple Sclerosis Outcomes Study Group. Neurology. 1999;52(1):63-70. doi:10.1212/wnl.52.1.63

Schwartz CE, Powell VE. The Performance Scales disability measure for multiple sclerosis: use and sensitivity to clinically important differences. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):47. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0614-z

Ritvo P, Fischer J, Miller D, Andrews H, Paty D, LaRocca N. Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory: A user's manual. National MS Society; 2015.

Amtmann D, Kim J, Chung H, et al. Comparing CESD-10, PHQ-9, and PROMIS depression instruments in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59(2):220-229. doi:10.1037/a0035919

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77-84.

Pek J, Wong O, Wong A. How to address non-normality: a taxonomy of approaches, reviewed, and illustrated. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2104. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02104

Gromisch ES, Fiszdon JM, Kurtz MM. The effects of cognitive-focused interventions on cognition and psychological well-being in persons with multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020;30(4):767-786. doi:10.1080/09602011.2018.1491408

van den Akker LE, Beckerman H, Collette EH, Eijssen IC, Dekker J, de Groot V. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2016;90:33-42. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.09.002

Hind D, Cotter J, Thake A, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of depression in people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:5. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-14-5

Benedict RH, DeLuca J, Phillips G, et al. Validity of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test as a cognition performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23(5):721-733. doi:10.1177/1352458517690821

Jette AM, Tao W, Haley SM. Blending activity and participation sub-domains of the ICF. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(22):1742-1750. doi:10.1080/09638280601164790

Yorkston KM, Kuehn CM, Johnson KL, Ehde DM, Jensen MP, Amtmann D. Measuring participation in people living with multiple sclerosis: a comparison of self-reported frequency, importance and self-efficacy. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(2):88-97. doi:10.1080/09638280701191891

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: The study was supported by a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG 4815A2/2).

PRIOR PRESENTATION: The data were presented as a poster at the Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; May 28-June 1, 2019; Seattle, WA.