Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

CME/CNE Information

Activity Available Online:

To access the article, post-test, and evaluation online, go to http://www.cmscscholar.org.

Target Audience:

The target audience for this activity is physicians, physician assistants, nursing professionals, and other health-care providers involved in the management of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Learning Objectives:

1) Recognize common and potentially serious complications of hip and knee arthroplasty in patients with MS.

2) Identify potential benefits in terms of pain control and mobility that can be expected from hip and knee arthroplasty.

Accreditation Statement:

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and Delaware Media Group. CMSC is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Physician Credit

The CMSC designates this journal-based activity for a maximum of 0.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s) ™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Nurse Credit

The CMSC designates this enduring material for 0.5 contact hours (none in the area of pharmacology).

Disclosures:

Editor in Chief of the International Journal of MS Care (IJMSC), has served as Physician Planner for this activity. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.Francois Bethoux, MD,

has served as reviewer for this activity. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.Laurie Scudder, DNP, NP,

has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.Josef Maxwell Gutman, MD,

has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.Kelvin Kim, BA,

has received consulting fees from Smith & Nephew and Intelijoint that are unrelated to this work.Ran Schwarzkopf, MD, MSc,

served on the scientific advisory boards for Biogen and Genentech and received research support from the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Biogen, EMD Serono, Genzyme, and Novartis.Ilya Kister, MD,

One peer reviewer for the IJMSC has received consulting fees from Biogen, Sanofi Genzyme, Ibsen Pharmaceutical, and Teva and has done contracted research for Astellas, Merck, and Biogen. The other peer reviewer has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The staff at the IJMSC, CMSC, and Delaware Media Group who are in a position to influence content have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Note: Disclosures listed for authors are those applicable at the time of their work on this project and within the previous 12 months.

Method of Participation:

Release Date: October 1, 2018

Valid for Credit Through: October 1, 2019

In order to receive CME/CNE credit, participants must:

1) Review the continuing education information, including learning objectives and author disclosures.

2) Study the educational content.

3) Complete the post-test and evaluation, which are available at http://www.cmscscholar.org.

Statements of Credit are awarded upon successful completion of the post-test with a passing score of >70% and the evaluation.

There is no fee to participate in this activity.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use:

This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not approved by the FDA. CMSC and Delaware Media Group do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of CMSC or Delaware Media Group.

Disclaimer:

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any medications, diagnostic procedures, or treatments discussed in this publication should not be used by clinicians or other health-care professionals without first evaluating their patients' conditions, considering possible contraindications or risks, reviewing any applicable manufacturer's product information, and comparing any therapeutic approach with the recommendations of other authorities.

Abstract

Background:

Hip and knee replacements for osteoarthritis are established procedures for improving joint pain and function, yet their safety in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) is unknown. Patients with MS face unique surgical challenges due to underlying neurologic dysfunction. Current literature on arthroplasty in MS is limited to case reports focusing on adverse events.

Methods:

Of 40 identified patients who underwent hip or knee replacement, 30 had sufficient data for inclusion. We reviewed their medical records and recorded reasons for surgery, age at surgery, MS characteristics, surgical complications, and ambulatory aid status before and after surgery. We supplemented medical record review with questionnaires regarding preoperative and postoperative pain and satisfaction with surgical outcomes.

Results:

Median follow-up was 26 months. Complications of surgery were reported in ten patients (33%), mostly mild and self-limited, although four patients (13%) required repeated operation. Six patients (20%) reported improvements in ambulatory aid use compared with presurgery baseline, ten (33%) worsened, and 14 (47%) were unchanged. In 20 patients who completed the questionnaire, mean ± SD joint pain scores (on 0–10 scale) decreased from 8.6 ± 2.0 preoperatively to 2.9 ± 2.4 postoperatively (P < .001). Five patients (25%) were free of joint pain at last follow-up.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that pain reduction is a realistic outcome of total knee or hip arthroplasty in people with MS and that improved functional gait outcomes are possible in some patients. Prospective, multicenter, collaborative studies are needed to optimize selection and improve outcomes in people with MS considering arthroplasty.

Hip and knee replacements for osteoarthritis are well-established procedures that have been performed on more than 7 million people in the United States,1 yet their safety and effectiveness in persons with multiple sclerosis (MS) is unknown. Multiple sclerosis is a neurologic disorder that causes progressive disability and gait dysfunction. It is estimated that the proportion of people with MS who need an ambulatory aid such as a cane increases from 25% after 10 years from disease onset to 40% after 20 years and 50% after 30 years.2 Patients with MS are also prone to musculoskeletal comorbidity, with prevalence estimates ranging from 13.7% to 54.3%.3 Surgical selection in patients with MS who are considering arthroplasty is complicated by general debility, which may interfere with rehabilitation, and by spasticity, which may affect the longevity of the hip or knee prosthesis.4 Moreover, immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive medications for MS may impair healing and lead to higher infection rates.5 Thus, outcomes of arthroplasty in the general population cannot be extrapolated to persons with MS. At the same time, the need for joint replacement may be higher in people with MS than in the general population because people with MS, in addition to primary osteoarthritis, also develop secondary osteoarthritis and are prone to traumatic falls and avascular necrosis (AVN) due to corticosteroid use. Prevalence estimates of knee replacement in MS range from 1% to 1.5% and of hip replacement, from 0.5% to 1.5%.3

To our knowledge, a systematic review of outcomes of knee and hip replacements in persons with MS has not been performed. The literature is limited to case reports and case series that focus on adverse events,4–8 such as a series of four patients with MS with knee replacement, all of whom required repeated operation for aseptic failure or instability.5 These reports, although instructive, cannot be used to assess risks and benefits of these procedures in people with MS.

Given the knowledge gap, we set out to conduct a retrospective analysis of outcomes in all people with MS seen in our tertiary MS center who have undergone total hip or total knee replacement surgery after MS onset. The primary objective was to assess rates of common and potentially serious complications in patients with MS undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Secondary objectives included documenting changes in ambulatory aid use over time, pain levels, and patient satisfaction with surgery.

Methods

Study Cohort

After approval was received from the NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, we searched the electronic medical records (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) of patients seen at NYU MS Care Center (New York, NY) from January 1, 2012, through December 31, 2016, who had billing codes related to total hip or knee arthroplasty (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] codes 27447/27487 and 27139/27132/27134 or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10], codes Z96.650/1/2 and Z96.60). Medical records identified in this search were then analyzed individually by an MS specialist (J.M.G.) to ensure that the patients met the following inclusion criteria: age older than 18 years, onset of MS symptoms before total hip or knee arthroplasty, clinician-defined diagnosis of MS by a fellowship-trained neurologist based on 2010 McDonald criteria at the last follow-up, and gait status available before and after surgery.

Data Collection

For patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria, we recorded age, sex, MS duration, MS disease-modifying therapy at surgery, and indication for surgery (eg, osteoarthritis or AVN). Perioperative details—date and type of surgery, surgical complications, postoperative length of stay, and discharge disposition—were recorded from operative reports where available and were supplemented by clinic notes and surveys. In patients with more than one joint replacement, only the most recent joint was analyzed. Patients who were seen for routine clinical follow-up at the NYU MS Center during the study period, between January 1, 2017, and June 30, 2017, were invited to complete a structured questionnaire designed to corroborate medical record data and elicit additional information regarding patient perceptions of surgery. From medical record review, patient report, or both, we collected information on the use of ambulatory aids before and after surgery as a surrogate marker of gait function. Ambulatory aid status was stratified as no ambulatory assistance, unilateral gait aid (cane or walking stick), bilateral gait aid (crutches, forearm crutches, or walker), and nonambulatory (wheelchair or bedbound). We classified gait aid by the neurologist's documentation of the patient's habitual gait aid and aid used during the office examination. Questionnaires included the visual analogue scale numeric pain rating, level of satisfaction with surgery based on a 5-point Likert scale (very satisfied, satisfied, uncertain, unsatisfied, very unsatisfied), and whether the patient would recommend surgery to others in similar conditions.

Statistical Analysis

All the data were collected and stored in a deidentified manner using Excel spreadsheet software (Microsoft Corp, Richmond, WA). Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). All the patient variables were reported using descriptive statistics consisting of mean ± SD for continuous variables and absolute values and percentages for categorical variables. A two-tailed Student t test was used to compare means of continuous variables (eg, patient-reported outcome scores). Significance was defined by P < .05.

Results

Study Population and Demographics

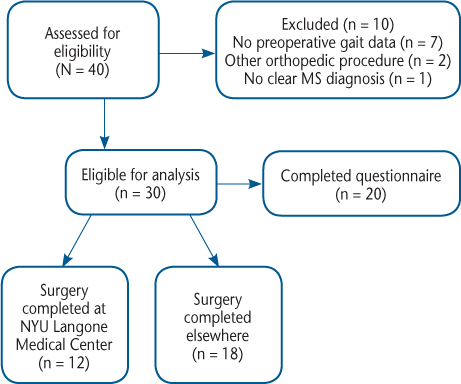

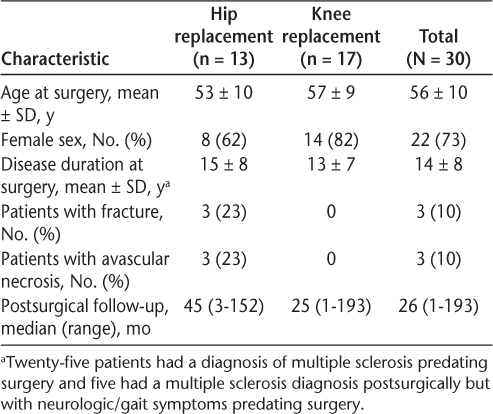

An initial search of the electronic medical record yielded 40 patients who were followed up at NYU MS Care Center and had an associated CPT or ICD-10 code for hip or knee replacement. Ten patients were excluded from further analysis: seven had no preoperative gait data, two had other orthopedic procedures (one with patellofemoral replacement and one with unicompartmental knee arthroplasty), and one did not have a definitive MS diagnosis. The final cohort consisted of 30 patients with MS, 20 of whom completed the questionnaire (Figure 1). Of the 30 patients, 25 had a known MS diagnosis before surgery and five had MS symptoms before surgery and diagnosis was confirmed after the procedure. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. Twelve patients underwent joint replacement surgeries at NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital, and their perioperative information (complications and discharge disposition) was gathered directly from their electronic medical records. For the remaining patients, perioperative history was collected from secondary sources (review of MS clinic notes and patient questionnaires).

Study flow diagram

Demographic information

Complications

Complications of surgery were reported for ten patients (33%); two patients had more than one complication. Perioperative complications were relatively minor and treatable: pneumonia in two patients, superficial wound infection in one, urinary tract infection in two, deep vein thrombosis in one, urinary retention in one, and anemia requiring transfusion in one. No MS relapses were recorded in the perioperative setting. There was no indication that spasticity worsened after surgery in any patient based on medical record review and patient surveys. Four patients (13%) required reoperation due to recurrent hip instability (n = 1), knee joint infection (n = 2), and aseptic knee joint loosening (n = 1), and three of these four patients recorded increased ambulatory aid use at last follow-up compared with before the initial joint replacement. Repeated operation occurred between 6 months and 4 years after the initial operation. Of patients with infectious complications, two were concurrently receiving natalizumab (wound infection, pneumonia); two, glatiramer acetate (pneumonia, joint infection); and three, no disease-modifying therapy for MS (two urinary tract infections, one joint infection).

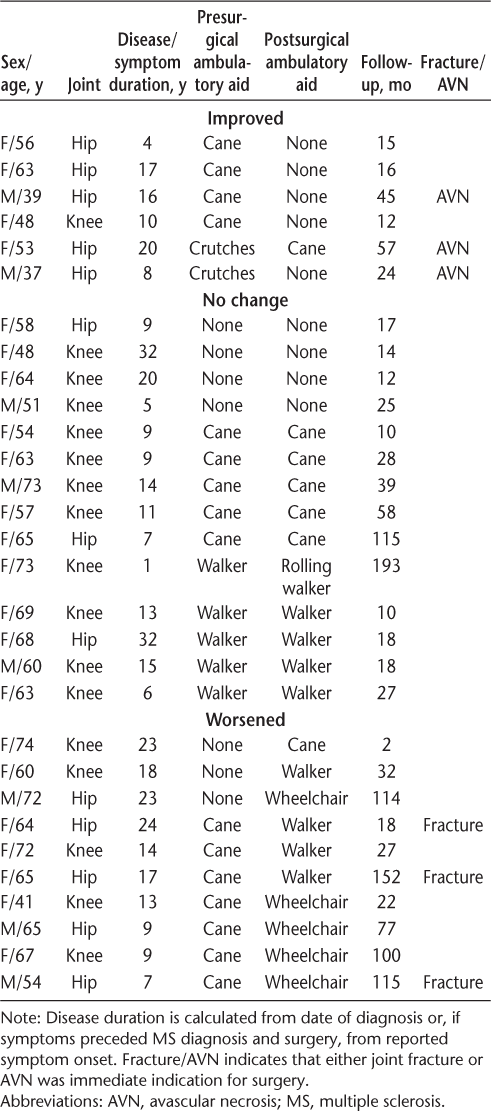

Ambulatory Aid Use

Use of ambulatory aids before surgery and at last follow-up for each of the 30 patients is shown in Table 2. Preoperatively, all 30 patients were ambulatory: seven without an assistive device, 16 with unilateral assistance, and seven with bilateral assistance. After median follow-up of 26 (range, 2–193) months, six patients (20%) had improved ambulatory aid status compared with before surgery (eg, from cane to no cane or from walker to cane), ten (33%) had worsened, and in 14 (47%) ambulatory aid status was unchanged. All three patients with hip replacement after AVN had improvement in use of assistance at last follow-up. Three patients with surgery after hip fracture needed increased ambulatory aid use at last follow-up.

Outcomes of total joint arthroplasty in 30 patients with MS by ambulatory aid use

Patient-Reported Outcomes

All 20 patients who completed the structured questionnaire reported joint pain preoperatively. Sixteen of them (80%) reported that surgery improved their joint pain, two (10%) found that the surgery did not help the pain (one with knee replacement and one with hip replacement), and two (10%) were unsure (both with knee replacement). Mean ± SD pain scores decreased from 8.6 ± 2.0 preoperatively to 2.9 ± 2.4 postoperatively (P < .001). Five patients (25%) were free of joint pain at the last follow-up (three with knee replacements and two with hip replacements).

When asked whether they would recommend surgery to others in similar conditions, 14 patients (70%) responded that they would recommend it, three (15%) would not recommend it, and three (15%) were unsure. Of the three patients who would not recommend surgery, two recorded no or uncertain improvement in pain. On a scale of satisfaction with surgery, 17 of 20 patients (85%) were satisfied or very satisfied with the surgery and three (15%) were very unsatisfied. No patients selected either the uncertain or the unsatisfied category. The three very unsatisfied patients were the same patients who would not recommend the surgery to others. Two of the very unsatisfied patients required repeated operation (see the Complications subsection); the third was a patient who reported no pain relief, had a urinary tract infection during surgery, and went from using no ambulatory device to using a wheelchair during follow-up.

Discussion

To make an informed decision about whether to proceed with total hip or knee arthroplasty, patients with MS need to know about their surgical risks and whether the surgery is likely to improve gait and joint pain. This case series provides some information that may be helpful to guide the decision. Complications, most of which were mild and self-limited, were recorded for 33% of patients, and four patients (13%) required a repeated operation due to joint instability, aseptic loosening, or periprosthetic infection. Three of four patients who underwent a second surgery had worse gait status at last follow-up compared with their preoperative status. The periprosthetic joint infection rate in the present patients (7%) seems to be relatively high compared with the 1% to 2% rate cited for the general total joint arthroplasty population.9 Neither of the two patients with periprosthetic infection was receiving immunosuppressive therapy at the time of surgery (one was taking glatiramer acetate and the other was off disease-modifying therapies). One complication that was potentially related to MS was urinary retention in one patient. No patients reported MS relapse perioperatively, which may be due to the relatively older age at the time of surgery, the mid-50s, when MS relapses are relatively uncommon.10

Most patients in the present series (80%) recorded the same or worse ambulatory aid status at the last postoperative follow-up compared with before surgery. These outcomes are not unexpected in patients with a progressive neurologic disorder. Interestingly, the three patients who underwent surgery for AVN all improved in their gait status after surgery, whereas the three patients who underwent surgery for hip fracture all worsened. The patients with AVN were younger than average relative to the cohort as a whole, and two of three patients with a hip fracture were older than average, which may have biased the outcomes for these two indications. Another possible caveat is that the patients who sustained hip fracture had impaired gait before fracture, and the postoperative gait aid status may be more of a reflection of their preoperative disability rather than surgery itself. Whether outcomes of hip/knee replacement in people with MS vary by indication is an important question that warrants a prospective study.

Joint pain outcomes after arthroplasty were encouraging: 25% of patients were free of joint pain at last follow-up, and 80% of patients reported improved pain postoperatively. Patients with pain improvement generally were satisfied or very satisfied with surgery, whereas patients without pain improvement were mostly very unsatisfied. An important limitation to these results is that pain levels preoperatively were assessed retrospectively and were, therefore, subject to recall bias.

Postoperative outcomes seen in the present patients with MS are similar to what has been reported in some other neurologic conditions. Patients with Parkinson disease who underwent hip replacement overwhelmingly had good-to-excellent pain relief, although approximately one-third experienced a complication and 8% required a repeated operation.11 In poliomyelitis, which, in contrast to MS, is a lower motor neuron disease, hip and knee replacement12,13 resulted in universal pain relief and was associated with a very low rate of hip dislocations. In stroke, an upper motor neuron disease that can cause spastic hemiparesis- or paraparesis-like MS, no difference in mortality rates after arthroplasty were observed in patients older than 50 years compared with control patients of the same age.14 Both stroke patients and elderly controls reported increased use of ambulatory aids after surgery, whereas patients with stroke had poorer ambulation at baseline.14 An important point of distinction between stroke and MS is that patients with MS usually receive immunomodulatory therapy. A study of Medicare claims found that patients with rheumatologic disease, who also use immunomodulatory medications, found a hazard ratio of 1.7 for periprosthetic joint infection, the highest of any of the comorbidities investigated.15

The strengths of this study include unbiased inclusion of all patients with MS with hip/knee replacement in our clinic; supplementation of clinical data from medical record review, with patient-reported outcomes obtained through structured questionnaire (in 66% of patients); and a relatively long follow-up (median, 26 months), which enabled us to assess both shorter- and longer-term outcomes. Limitations relate to the various biases attendant to observational studies, such as recall bias (eg, patients may not be able to accurately recall their ambulatory status before surgery), incomplete data on surgery and prosthesis (complete data were available only for the 40% of patients operated on at NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital), and selection bias (questionnaires were collected only for patients who were actively followed at the outpatient clinic). Patients who continue to be actively followed up in the clinic may differ from those who are lost to follow-up, although it is difficult to predict whether this difference might bias results in a more favorable direction (eg, if patients with better outcomes are more likely to follow up) or an unfavorable direction (eg, if patients with worse outcomes are more likely to seek further help from clinicians). We used mobility aid status as a surrogate marker of gait function because Expanded Disability Status Scale scores were not prospectively recorded for these patients. Finally, combining hip and knee surgeries for the purposes of analysis is a standard practice in the orthopedic literature, but it is possible that outcomes of the two procedures in patients with MS are not identical.

The present retrospective work involved a thorough search of medical records for all patients seen in a large academic center who had hip or knee arthroplasty after MS symptom onset. This series seems to be the largest to date to document complications and patient-reported outcomes in arthroplasty in patients with MS. These results suggest that pain reduction is a realistic outcome of a total knee or hip arthroplasty in people with MS and that improved functional gait outcomes are possible in a minority of patients. These benefits must be balanced against the risk of complications and the increased need for an assistive device in some patients. These results could inform the discussion between patients with MS contemplating arthroplasty and their treating neurologists and orthopedic surgeons. In the future, it would be of interest to compare short- and long-term outcomes in patients with MS who have a similar baseline risk of MS progression, disability level, and joint pathology. We advocate for prospective, multicenter, collaborative studies to optimize selection and improve outcomes in patients with MS who are considering total joint arthroplasty.

PRACTICE POINTS

Complications were seen in 33% of patients with MS undergoing total joint arthroplasty; these complications were generally mild and self-limited, but four patients (13%) required a repeated operation due to joint instability, aseptic loosening, or periprosthetic infection.

An overwhelming majority of patients with MS reported improved or no joint pain at last follow-up after arthroplasty, and 20% recorded improvements in ambulatory aid status.

Further studies are needed to optimize patient selection and operative techniques in patients with MS who are candidates for hip or knee replacement.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Schwarzkopf has received consulting fees from Smith & Nephew and Intelijoint that are unrelated to this work. Dr. Kister served on the scientific advisory boards for Biogen and Genentech and received research support from the Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, Biogen, EMD Serono, Genzyme, and Novartis. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1386–1397.

Kister I, Chamot E, Salter AR, Cutter GR, Bacon TE, Herbert J. Disability in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;80:1018–1024.

Marrie RA, Reider N, Stuve O, et al. The incidence and prevalence of comorbid gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, ocular, pulmonary, and renal disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2015;21:332–341.

Dawson-Bowling S, Tavakkolizadeh A, Cottam HL, Butler-Manuel PA. Multiple sclerosis and bilateral dislocations of total knee replacements: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;16:148–151.

Hughes KE, Nickel D, Gurney-Dunlop T, Knox KB. Total knee arthroplasty in multiple sclerosis. Arthroplasty Today. 2016;2:117–122.

Bron JL, Saouti R, De Gast A. Posterior knee dislocation after total knee arthroplasty in a patient with multiple sclerosis: a case report. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73:118–121.

Rao V, Targett JPG. Instability after total knee replacement with a mobile-bearing prosthesis in a patient with multiple sclerosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:731–732.

Shannon FJ, Cogley D, Glynn M. Total knee replacement in patients with multiple sclerosis. Knee. 2004;11:485–487.

Segreti J, Parvizi J, Berbari E, Ricks P, Berríos-Torres SI. Introduction to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection: Prosthetic Joint Arthroplasty Section. Surg Infect. 2017;18:394–400.

Tremlett H, Zhao Y, Joseph J, Devonshire V; UBCMS Clinic Neurologists. Relapses in multiple sclerosis are age- and time-dependent. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:1368–1374.

Weber M, Cabanela ME, Sim FH, Frassica FJ, Harmsen SW. Total hip replacement in patients with Parkinson's disease. Int Orthop. 2002;26:66–68.

Gan Z-WJ, Pang HN. Outcomes of total knee arthroplasty in patients with poliomyelitis. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:2508–2513.

Yoon B-H, Lee Y-K, Yoo JJ, Kim HJ, Koo K-H. Total hip arthroplasty performed in patients with residual poliomyelitis: does it work? Clin Orthop. 2014;472:933–940.

Nho J-H, Lee Y-K, Kim YS, Ha Y-C, Suh Y-S, Koo K-H. Mobility and one-year mortality of stroke patients after hip-fracture surgery. J Orthop Sci. 2014;19:756–761.

Bozic KJ, Lau E, Kurtz S, et al. Patient-related risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection and postoperative mortality following total hip arthroplasty in Medicare patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:794–800.