Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Testing of Journal Writing for Symptom Concordance in Adults with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Adults with multiple sclerosis (MS) experience many complex symptoms. However, research is lacking on the best method to record their symptom experience. The primary goal of this study was to test the feasibility of journal writing to capture the description of core symptoms experienced by adults with MS. A secondary goal was to collect self-report symptom data to assess concordance between the journal entries and MS-Related Symptom Checklist (MS-RS) scores.

Methods:

A preselected group of participants (n = 5) from the total sample of 16 participants with MS were asked to complete the revised MS-RS and Web-based journal writing for 20 minutes per day for 4 consecutive days over a 4-week period. Feasibility was evaluated by journal completion rates.

Results:

Most participants found journal writing acceptable as a method for writing about symptoms. Participants were able to write about symptoms that formed clusters: unpredictable physical alterations and unpredictable sensory and emotional changes. Likewise, participants reported frequent fatigue, difficulty sleeping, heat intolerance, and difficulty concentrating/cognitive problems from the revised MS-RS. Disconcordance between revised MS-RS data and journal entries included lack of disclosure of difficulty sleeping and “pins and needles” in the journals.

Conclusions:

Preliminary findings from this study provide the personal perspectives of core symptoms experienced by adults with MS. These results provide preliminary evidence of the feasibility of journal writing, along with self-report survey, to describe symptoms in adults with MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory, autoimmune, neurodegenerative disease. It is the most common neurologic cause of disability in young adults.1 The annual prevalence rate of being diagnosed as having MS in the United States is approximately 1 million.2 This prevalence rate is larger than previously reported in the literature.1,2 The most common symptoms of MS include fatigue,2–5 anxiety/depression,3–6 heat intolerance,4,7–9 visual disturbances, balance and walking difficulties,10–14 bladder/bowel sphincter dysfunction,9 and pain.5,11,14,15 Symptoms of MS are unpredictable and vary from person to person. Thus, it is important to capture the personal experience of core symptoms expressed in the words of adults with MS. Previous research has primarily focused on a single symptom (eg, fatigue) experienced by adults with MS.3,4,6 However, multiple symptoms of MS often occur concurrently.4,5,8,12,15 Two or more symptoms that are related to each other and occur together are defined as a symptom cluster.5,15 To date, reporting of symptom clusters in adults with MS has been a challenge due to the identified limitations of items on existing MS-focused symptom instruments (eg, not sensitive to the patient’s perceived experience). Thus, capturing data on the personal perspectives about symptoms experienced may address the challenge of understanding symptom clusters and provide evidence for symptom management care of adults with MS.15,16

Existing published evidence has shown that the experience of MS symptoms among adults can greatly vary14–17 and, therefore, may not be captured accurately among items listed on existing MS symptom assessment surveys.16,18 Due to the highly personalized experience of MS symptoms, use of a journal as a way to describe symptoms is a unique data collection method. Likewise, the use of qualitative daily journal writing has the potential to collect MS symptoms of concern more fully and to allow affected adults to categorize their symptoms in the order of importance. Symptom journals have been used to collect symptom information among adults with MS.16,19 Based on the literature,16,19,20 it is anticipated that journal writing can be used to glean qualitative descriptions of patients’ perceived symptoms. Rather than contrasting each individual’s report of their symptoms, an advantage may be to examine the concordance between symptom journals and self-report surveys. Although much research has assessed MS symptoms in adults using a variety of surveys, few studies have sought to examine the concordance of symptom journals and self-report surveys.

The primary objective of this pilot study was to test the feasibility of using Web-based journal writing in a subset of adults with MS to describe their symptoms of concern. A secondary goal was to collect self-report symptom data using the MS-Related Symptom Checklist (MS-RS) to compare with the qualitative journal data.

Methods

Sample and Setting

This study was approved by the institutional review board before data collection. A purposive sampling technique was used to construct a diverse sample to increase the likelihood of collecting a wide range of symptoms and the perspectives and related symptom experiences of adults with MS. Participants were recruited from a Midwestern metropolitan community.

We included individuals 1) diagnosed as having MS and having relapsing-remitting or secondary progressive MS, 2) aged 18 years or older, 3) with the ability to speak and understand English, and 4) with access to and having the ability to use a computer, the internet, and e-mail.14 We excluded adults with MS who could not follow the interview or consent directions or had a chart-recorded diagnosis of cognitive dysfunction.

Procedures

During the enrollment visit, adults with MS were 1) invited to review and sign an informed consent form, 2) asked to provide their demographic information and e-mail address, and 3) asked to share their symptom occurrence using the revised self-report MS-RS.21 An e-mail notification describing the study and instructions was sent through an automatic REDCap messaging system. This e-mail included a unique password-protected identifier.

Symptom Journals

Symptom-focused questions were adapted from symptom journals used in studies that focus on symptom assessment in adults with cancer or cancer survivors22,23 as well as from previous MS focus groups to develop writing prompts.14 Enrolled participants were instructed to reflect and write about their symptoms for a maximum of 20 minutes. The authors reviewed the questions and evaluated the writing prompts. Sample prompts included “we want you to tell us everything you can about your MS-related symptoms” and “among these symptoms, please also describe the most frequent symptom you have experienced” (Appendix S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org).

Each writing session engaged the participants to focus on writing about their symptoms for 20 minutes per day for 4 consecutive days over a 4-week period—for a total of 16 writing sessions. Participants were provided with an e-mail and telephone number for a specified research member in the event that they had any questions, concerns, or difficulties during their sessions. All the participants were encouraged to write their responses in a self-selected, private location. Also, they were assured that their responses would remain completely confidential.

Secondary Outcome Measure

Revisions to the MS-RS were derived from focus groups in the principal investigator’s (P.N.’s) work. The original MS-RS21 consists of 26 symptoms commonly experienced by adults with MS. The revised MS-RS consists of 43 symptom items. The MS-RS total score ranges from 0 to 180, with a high score indicating the presence of many symptoms. The scale has strong reliability and validity.14,21

Enrolled participants also provided specified demographic information (ie, age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education) and clinical information (ie, types of current medications for MS, time since MS diagnosis) at enrollment.

Analysis

The testing of Web-based journal writing as a data collection tool was assessed using journal completion rates. Journal completion rates were calculated by completion of each journal daily over a 4-week period. Completion was considered feasible if at least 75% of participants completed the journals.

Qualitative data from journals were analyzed using content analysis methods. After coding all the writing transcripts, two coders (the primary author [P.N.] and a research assistant [S.S.]) independently sorted all relevant coded symptom data.24 The coders verified the accuracy and trustworthiness of the analyzed data from the journal entries. All writing content from each participant was transcribed. Then, themes were defined based on symptom groupings of specific words and frequency of the symptoms used.

Data were downloaded from REDCap and stored in a password-protected computer in preparation for data analysis. REDCap is compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standards. SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp) was used to analyze the quantitative symptom measures. Demographic characteristics were categorized using mean and SD. The MS-RS score was calculated using symptom frequencies.

Results

The final sample included five participants with MS. Following is a summary of the participants’ demographic information: 1) age range of 34 to 57 years (mean = 48 years), 2) four were married and one was single, and 3) completed years of education ranged from 14 to 17 years. Most or all participants reported being 1) employed full-time (n = 5), 2) White/non-Hispanic race/ethnicity (n = 4), and 3) female (n = 5).

Feasibility

Of the five participants who completed the writing sessions, two completed 100% of the desired 16 online writing sessions. Two of the remaining participants completed 75% of the online writing sessions, and one completed 50% of the online writing sessions. None of the enrolled participants withdrew from the study or had any questions for the research team. However, one participant had to be reminded via e-mail each week to complete the online journal writing entries.

Core Symptoms That Formed in Clusters

Participants described symptoms in two named clusters: unpredictable physical alterations and unpredictable sensory and emotional changes. The names reflected the experience provided in the excerpts (Table 1). Some of the core symptoms are also included in the clusters sensory and emotional.

Comparison of core symptoms forming the two symptom clusters using excerpts

Secondary Outcome

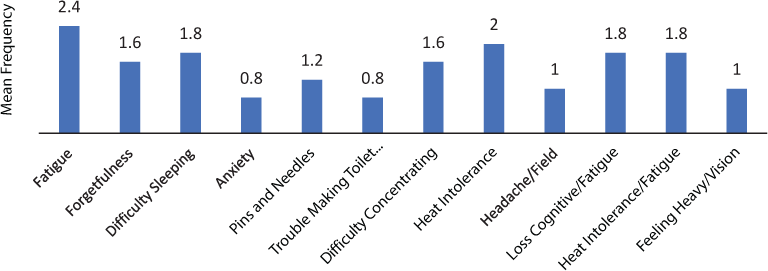

Of note, during journaling, participants reported similar symptoms (fatigue, weakness, and heat intolerance) to those on the MS-RS whereas other symptoms and the MS-RS were discordant. Specifically, core symptoms on the MS-RS were fatigue, difficulty sleeping, and heat intolerance (Figure 1).

Frequency of symptoms measured using revised MS-Related Symptom Checklist

Discussion

To our knowledge, this pilot study is the first to report the feasibility of Web-based journal writing to describe symptoms in adults with MS. Web-based journal writing about MS symptoms for 20 minutes a day over a 4-week period seemed to be feasible and has the potential to identify core symptoms that formed clusters experienced by adults with MS. The use of journal writing empowered adult participants with MS to record and share their current MS symptoms of concern. This method also provided preliminary evidence of the benefits of using this method in addition to symptom surveys to capture a more thorough assessment of currently experienced MS symptoms. For instance, a few differences were found between the participants’ journal writing about their symptoms and their MS-RS scores. Previous studies have found these types of differences between self-report and proxy,25–27 especially in terms of symptoms that adults with MS may not interpret as being MS-related. For example, adults with MS may not always recognize sleep difficulty as being MS-related, which was suggested by difficulty sleeping not being mentioned in the journal writing. The apparent disagreement between symptom reporting in the journals and the MS-RS could be due to the terminology used on the MS-RS or to the lack of recall due to the onetime administration at enrollment. The journal excerpts (Table 1) paint the picture of the personal experience of symptoms. Thus, future studies of the dynamics of using journal writing to glean the personal symptom experience are important.

When feasible and applicable, it may be useful to assess for all symptoms within a cluster, such as fatigue, depression/mood disturbances, weakness, and heat intolerance, during provider communications. The present results suggest that targeted writing could potentially be useful to obtain the personal symptom experience of adults with MS.14,28 In particular, journal writing incorporated with surveys may allow for more accurate description of MS symptoms. Journal writing may uncover distinct symptoms that may otherwise seem similar, such as anxiety or apathy versus depression; this may especially be useful if surveys are administered well after the experience of various symptoms. Future studies are needed using journal writing to capture symptoms that form clusters in a larger sample of adults with MS.

These findings should be interpreted with caution given the limitations of a feasibility study with a small subset of adults with MS. However, small samples are often used when testing feasibility and collecting pilot data.29 The present sample was homogenous in terms of sex, racial/ethnic background, educational background, and disability level/functional status; however, the results cannot be generalized to more diverse or more impaired groups of adults with MS. Inclusion of a wider variety of adults with MS (eg, MS subtypes) should be prioritized in future studies to determine whether integrating journal writing with self-report is useful.

Although adults with MS experience a gamut of symptoms (eg, tremor, cognitive), which might have hindered the completion of all journal entries, we believe it is more likely that the lower rate of completion for some participants was due to the demands of the journaling task (20 minutes a day for 4 weeks). It is not possible to know if, for example, a 50% completion rate provides enough information because too little is known about dose response30 related to journal writing. One possible solution would be to decrease the number of writing sessions in terms of both frequency and length. We also recommend that data collection procedures include the plan to have a research assistant call or text each participant to monitor and encourage the completion of journal writing activities, to identify potential barriers (eg, environmental distractions, home responsibilities, MS symptoms), and to address any questions. Studies are lacking regarding the impact of dose response or whether 100% completion results yield better outcomes. Studies have shown that adults with MS are able and willing to complete written journals despite such symptoms.19 Of note, the MS-RS was administered one time at enrollment, which, thus, may explain the differences in response. We emphasize the pilot nature of this study. Therefore, it is important to investigate barriers to journal completion (eg, length of time for completion, dose response, potential personal or environmental barriers) in future studies.

In conclusion, preliminary findings from this pilot study provide preliminary evidence of the personal perspectives of core symptoms experienced by adults with MS. These results also provide preliminary evidence that the use of journal writing is an effective strategy to capture the perspectives of adults with MS about their current symptoms and symptoms of concern that may be affecting their quality of life. Follow-up studies using journal writing could facilitate symptom assessment in adults with MS. We recommend investigators consider using journal writing as a qualitative method to collect individual perspectives about symptoms experienced by individuals with MS. Use of more than one data-collection method (self-report responses on measures and journaling) will increase the knowledge base of MS symptoms and symptom clusters and will help assist clinicians to provide quality care to patients with MS.

PRACTICE POINTS

Journal writing is a feasible method for adults with MS to describe their MS symptoms.

In this study, adults with MS were able to describe their core symptoms, forming clusters.

Future studies are warranted that include journal writing along with self-report surveys to describe symptoms.

Financial Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Dobson R, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis: a review. Eur J Neurol. 2019; 26: 27– 40.

Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, . The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019; 92: e1029– e1040.

Tabrizi FM, Radfar M. Fatigue, sleep quality, and disability in relation to quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015; 17: 268– 274.

Jones SMW, Salem R, Amtmann D. Somatic symptoms of depression and anxiety in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018; 20: 145– 152.

Zhang W, Becker H, Stuifbergen AK, Brown A. Predicting health promotion and quality of life with symptom clusters and social supports among older adults with multiple sclerosis. J Gerontol Nurs. 2017; 43: 27– 36.

Amtmann D, Askew RL, Kim J, . Pain affects depression through anxiety, fatigue, and sleep in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2015; 60: 81– 90.

Alschuler KN, Ehde DM, Jensen MP. Co-occurring depression and pain in multiple sclerosis. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2013; 24: 703– 715.

Newland P, Flick LH, Hong X, Thomas F. Symptom co-occurrences associated with smoking in individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2016; 18: 163– 168.

Roberg BL, Bruce JM. Reconsidering outdoor temperature and cognition in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2016; 22: 694– 697.

Norbye AD, Midgard R, Thrane G. Spasticity, gait, and balance in patients with multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Physiother Res Int. 2020; 25: e1799.

Łabuz-Roszak B, Niewiadomska E, Kubicka-Bączyk K, . Prevalence of pain in patients with multiple sclerosis and its association with anxiety, depressive symptoms and quality of life. Psychiatr Pol. 2019; 53: 475– 486.

Newland P, Salter A, Flach A, . Associations between self-reported symptoms and gait parameters using in-home sensors in individual with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Nurs. 2020; 45: 80– 87.

Kalron A. The correlation between symptomatic fatigue to definite measures of gait in people with multiple sclerosis. Gait Posture. 2016; 44: 178– 183.

Newland PK, Thomas FP, Riley M, Flick LH, Fearing A. The use of focus groups to characterize symptoms in individual with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012; 44: 351– 357.

Shahrbanian S, Duquette P, Kuspinar A, Mayo NE. Contribution of symptom clusters to multiple sclerosis consequences. Qual Life Res. 2015; 24: 617– 629.

Harrison AM, Bogosian A, Silber E, McCracken LM, Moss-Morris R. ‘It feels like someone is hammering my feet’: understanding pain and its management from the perspective of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015; 21: 466– 476.

Greiner P, Sawka A, Imison E. Patient and physician perspectives on MSdialog, an electronic PRO diary in multiple sclerosis. Patient. 2015; 8: 541– 550.

Kratz AL, Braley TJ, Foxen-Craft E, Scott E, Murphy JF III, Murphy SL. How do pain, fatigue, depressive, and cognitive symptoms relate to well-being and social and physical functioning in the daily lives of individuals with multiple sclerosis? Arch Phys Med Rehabil . 2017; 98: 2160– 2166.

Newland P, Lorenz RA, Smith JM, Dean E, Newland J, Cavazos P. The relationship among multiple sclerosis-related symptoms, sleep quality, and sleep hygiene behaviors. J Neurosci Nurs. 2019; 51: 37– 42.

Newland P, Lorenz R, Thomas F, Bordner M. Initial evaluation of an electronic sleep/symptom diary for adults with multiple sclerosis. MEDSURG Nurs. 2017; 26: 403– 409.

Gulick EE. Model confirmation of the MS-Related Symptom Checklist. Nurs Res. 1989; 38: 147– 153.

Lopez V, Copp G, Brunton L, Molassiotis A. Symptom experience in patients with gynecological cancers: the development of symptom clusters through patient narratives. J Support Oncol. 2011; 9: 64– 71.

Henry EA, Schlegel RJ, Talley AE, Molix LA, Bettencourt BA. The feasibility and effectiveness of expressive writing for rural and urban breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010; 37: 749– 757.

Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology . 2nd ed. SAGE Publications; 2004.

Li M, Harris I, Lu ZK. Differences in proxy-reported and patient-reported outcomes: assessing health and functional status among Medicare beneficiaries. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015; 15: 62.

Amara AW, Chahine L, Seedorff N, . Self-reported physical activity levels and clinical progression in early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019; 61: 118– 125.

Sonder JM, Balk LJ, Bosma LV, Polman CH, Uitdehaag BM. Do patient and proxy agree? long-term changes in multiple sclerosis physical impact and walking ability on patient-reported outcome scales. Mult Scler. 2014; 20: 1616– 1623.

Cerasoli B, Canevelli M, Vellucci L, Rossi PD, Bruno G, Cesari M. Adopting a diary to support an ecological assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019; 23: 614– 616.

Stone AA, Shiffman S, Schwartz JE, Broderick JE, Hufford MR. Patient compliance with paper and electronic diaries. Control Clin Trials. 2003; 24: 182– 199.

Smith B, Shatté A, Perlman A, Siers M, Lynch WD. Improvements in resilience, stress, and somatic symptoms following online resilience training: a dose-response effect. J Occup Environ Med. 2018; 60: 1– 5.