Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Effect of Health Care Providers’ Focused Discussion and Proactive Education About Relapse Management on Patient Reporting of Multiple Sclerosis Relapse

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Treatments for multiple sclerosis (MS) relapse include intravenous corticosteroids and repository corticotropin injection. Despite available treatment, in the Multiple Sclerosis in America 2017 survey, only 47% of patients reported always/often contacting their MS health care provider (HCP) during relapse. In this study, the Multiple Sclerosis in America 2017 survey participants who received intravenous corticosteroids or repository corticotropin injection for treatment of past relapses completed a follow-up survey to understand how patients characterize relapse severity and to explore predictors of patients contacting their HCP during a relapse.

Methods:

Patients were 18 years and older, diagnosed as having MS by an HCP, and currently using disease-modifying therapy. Patients completed an online survey assessing relapse characteristics and interactions with the HCP treating the patient’s MS. Regression analysis identified predictors of patients contacting their HCP during relapse.

Results:

Mean age of the 126 respondents was 49.2 years, 81.0% were female, and most (80.2%) had one or more relapses in the past 2 years. Patients estimated that 38.3% of their relapses were mild; 45.1%, moderate; and 16.6%, severe. Number and frequency of symptoms increased with relapse severity. Less than half (46.0%) reported they were extremely likely to contact their HCP during a relapse. The best predictors of being likely to contact the HCP during relapse were the HCP having previously discussed the importance of immediately communicating a relapse and patients’ willingness to accept the HCP’s recommendation for relapse treatment.

Conclusions:

Findings highlight the importance of HCPs’ advance discussions with patients with MS regarding relapse management to increase the likelihood patients will contact their HCP during relapse.

Relapses are a defining feature of multiple sclerosis (MS), occurring in approximately 90% of patients with MS and particularly in patients with relapsing-remitting MS.1,2 Relapses are characterized by exacerbations of neurologic disability lasting more than 1 day and for as long as a few months, followed by partial or complete remission.1–3 Studies have shown that relapses can leave behind worsening and permanent neurologic deficits.1,2,4,5 Relapses also cause substantial patient burden in terms of missed work and school, reduced income, and difficulty maintaining daily activities.6,7

Use of disease-modifying therapy (DMT) can reduce the occurrence of relapses in patients with MS, and reduction of relapses is a primary goal of ongoing therapy.2 However, DMT is not a treatment for relapses themselves. When relapses do occur, acute therapy can reduce their severity and duration.4,5 Severe relapses are typically treated with a high-dose course of intravenous (IV) corticosteroids or oral corticosteroids.3,8–10 Relapses are a manifestation of inflammation in the central nervous system,3 and IV corticosteroid treatment is thought to reduce this inflammation.3,8 Repository corticotropin injection (RCI; Acthar Gel, Mallinckrodt ARD LLC), a naturally sourced complex mixture of adrenocorticotropic hormone analogs and other pituitary peptides,11 is also approved to treat relapses and is often prescribed to patients who have not tolerated or experienced relief from previous treatments with IV corticosteroids or who have difficulty obtaining IV treatment.3,8 Both IV corticosteroids and RCI are effective for treatment of relapses.3,10,12 Plasmapheresis and IV immunoglobulin treatment may also be considered, although the safety and efficacy of these two treatment options for MS exacerbations have not been established by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,8

Despite the availability of effective treatment to shorten and reduce the severity of MS relapses, patients do not always communicate the occurrence of relapse symptoms to their health care providers (HCPs).2 Patients sometimes think that reporting a mild relapse is unnecessary, that their symptoms will not be taken seriously, or that there is nothing that their HCPs can do.6 In addition, some patients may feel that past treatment during relapses was not effective or caused unpleasant adverse effects.13

To better understand patients’ interactions with their HCPs in the context of MS relapse, Nazareth and colleagues14 used data from Health Union’s Multiple Sclerosis in America (MSIA) 2017 survey of 5311 adult patients with MS. Of all responding patients, 73% had had one or more relapses during the previous 2 years, with a median of two relapses during that period.14 Less than half (47%) of the patients reported always or often contacting their MS HCPs during a relapse. Patients’ most common reasons for not engaging their HCPs during a relapse were that the relapse was not severe enough (58%), that the HCP was unhelpful or had not told the patient to contact them during relapse (31%), and that relapse medications were not effective or well tolerated (26%).14 Patients who engaged more often with their HCPs during relapse were more likely to report that key topics were discussed during those interactions, including symptoms and severity of the relapse and treatments for relapse, than patients who engaged with their HCPs less often.14

In the present study, patients who participated in the original MSIA survey14 and had been treated with IV corticosteroids or RCI for relapse were recontacted and completed a follow-up survey. The objectives of this study were to understand how patients characterize different levels of relapse severity and to further explore factors involved in patients’ decisions to contact their MS HCPs during a relapse.

Methods

Study Design

The MSIA survey14 was created by Health Union, a company that cultivates online communities dedicated to supporting patients with specific health conditions, including MS. The original survey14 was conducted by Health Union during the first quarter of 2017 and was administered to patients with MS and their caregivers via multiple online sources, including MultipleSclerosis.net and Facebook. MultipleSclerosis.net is an established online health community of approximately 230,000 unique visitors from the United States and more than 110,000 Facebook followers (data from first quarter of 2017). The present follow-up survey was conducted from January 19, 2018, to February 26, 2018.

The follow-up survey and recruitment assets were submitted to the Pearl Institutional Review Board and received an exemption determination. An honorarium of $15 in the form of an e-gift card was offered to survey completers, and standard data privacy and confidentiality procedures were followed.

Patients

In MSIA 2017, patient respondents were required to be at least 18 years old; to have been diagnosed as having relapsing-remitting MS, primary progressive MS, or secondary progressive MS by an HCP; and to live in the United States.

Respondents from the original MSIA survey14 with previous use of IV corticosteroids or RCI for MS relapse were contacted again to take part in an online survey to assess patient decision-making processes during MS relapse episodes. Sufficient numbers of patients receiving each relapse treatment (intended numbers: 55–80 patients who had received IV corticosteroids and 55–80 who had received RCI) were included to facilitate treatment comparisons, which are not reported in this paper. If necessary, reminders were sent to respondents until the target number of patients (55–80) was achieved for each treatment cohort. Patients were required to be currently using DMT and to provide responses consistent with their responses in the original MSIA survey for age, sex, and time since diagnosis (within 3 years).

Measures

The original MSIA survey consisted of 124 patient-directed questions. The follow-up survey consisted of 55 patient-directed questions. This article reports findings from a subset of questions from the follow-up survey (Appendix S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org). Patients were queried for demographic information, frequency and severity of relapses, symptoms associated with relapses, use of medications, including DMT and treatment during past relapses, and interactions with the HCP who was treating the patient’s MS. The Patient-Determined Disease Steps15 scale level was included.

Statistical Methods

Responses were recoded to facilitate interpretation. Means were calculated for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Between-group differences were analyzed using a t test for continuous variables. For categorical variables, a Z test was used except for small sample sizes (n ≤ 5), when a Fisher exact test was conducted.

A logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify variables predicting a respondent being “extremely likely” to contact their HCP during a relapse. A list of candidate predictors was developed from the survey, including attitudes, reported behaviors, and demographics. From the initial list of candidate predictors, univariate analyses were used to identify variables with significant relationships to the outcome variable. Highly collinear variables were excluded. A multiple logistic regression model was fit using the variables retained from the univariate analyses and the collinearity analyses. The significance of the variables in the final model was confirmed via the Wald statistic. A predictive index was calculated for each predictor variable; this index was the correlation of the individual predictor with the prediction of the best-fitting model. A P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

A total of 1376 patients who completed the earlier MSIA survey14 and who reported that they were taking a DMT and had received IV corticosteroids or RCI for relapse were contacted. Of these patients, 407 (29.6%) responded to the survey invitation. Of the 407 patients who initially responded, 205 (50.4%) did not meet the inclusion criteria on further screening and 74 (18.2%) who had received IV corticosteroids were not included because sufficient sample size had been reached. Reminders were sent to patients who had received RCI 5 and 10 days after the original e-mail invitation in an effort to reach the intended number of RCI recipients (55–80 patients). Respondents were given at least 1 week to complete the survey after the second reminder was sent.

In total, 126 patients completed the follow-up survey. The mean age of respondents was 49.2 years, 81.0% were female, and 88.9% were White (Table S1), similar to patients in the original survey.14 More patients were receiving disability benefits (53.2%) than were employed, and virtually all (99.2%) had health insurance coverage.

Disease and Relapse Characteristics

Mean age at diagnosis was 36.3 years, and most patients (87.3%) were currently diagnosed as having relapsing-remitting MS (Table S2). Most patients (53.2%) reported moderate disability; 30.2% reported mild disability, and 16.7% reported severe disability. All patients were prescribed DMT, and 93.7% reported that they “almost always” take the therapy as prescribed.

Of all the patients, 80.2% reported that they had experienced one or more relapses in the past 2 years (Table S2), with a median of two relapses per year. Of 101 patients who had experienced a relapse in the past 2 years, most had experienced both mild and moderate relapses (Table S2). On average, patients estimated that 38.3% of their relapses were mild, 45.1% were moderate, and 16.6% were severe.

Patients reported more relapse symptoms as perceived relapse severity increased: a mean of 6.2 symptoms with mild relapse, 7.8 symptoms with moderate relapse, and 9.2 symptoms with severe relapse. Across all severities of relapse, fatigue and spasticity were the most common patient-reported symptoms associated with relapse (Table S3). Bladder problems were also common during mild relapses, walking difficulties with moderate-to-severe relapses, and vision problems with severe relapses (Table S3).

Patients reported more severe limitations associated with more severe relapses. For mild relapses, 4.7% of patients experienced severe and 3.1% experienced very severe limitation of lifestyle and activities. For severe relapses, 29.7% of patients experienced very severe and 37.8% experienced complete limitation. Regarding duration of relapses, patients reported that most (>75%) mild relapses lasted less than 1 month, most moderate relapses lasted 2 weeks to 3 months, and most severe relapses lasted 1 month or longer.

Most patients (92.9%) had received IV corticosteroids, most commonly methylprednisolone, during a relapse (Table S2). More than two-thirds (71.4%) had received oral corticosteroids, and approximately one-third (34.1%) had received RCI during a relapse, reflecting the study’s inclusion criteria. Patients may have received different agents (IV corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids, or RCI) during separate relapses. Also, they may have received more than one agent for a relapse that persisted despite treatment (eg, oral corticosteroids followed by IV corticosteroids) or when tapering off to oral corticosteroids after inpatient treatment with IV corticosteroids.

Patterns of Contacting HCPs During Relapse

For 97.6% of responding patients, their MS was being treated primarily by a neurologist. Most patients reported seeing their HCP for MS management twice a year (46.0%) or more than twice a year (47.6%).

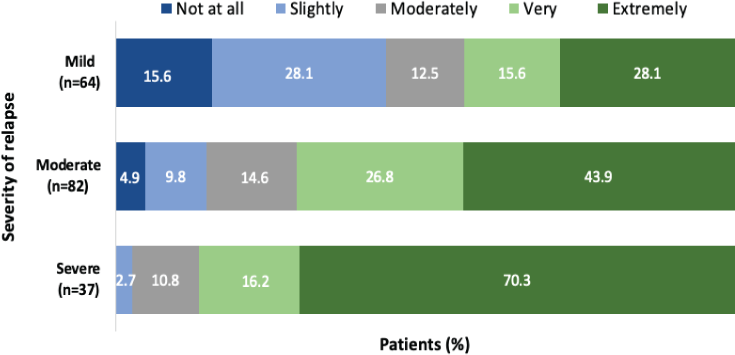

Of all the patients, 46.0% reported that they were “extremely likely” to contact their HCP during a relapse (Table S2). Patients were more likely to contact their HCP during severe or moderate relapses compared with mild relapses (Figure 1).

Likelihood of a patient contacting their MS health care provider during a relapse, by relapse severity (n = 101; some patients experienced relapses of more than one level of severity)

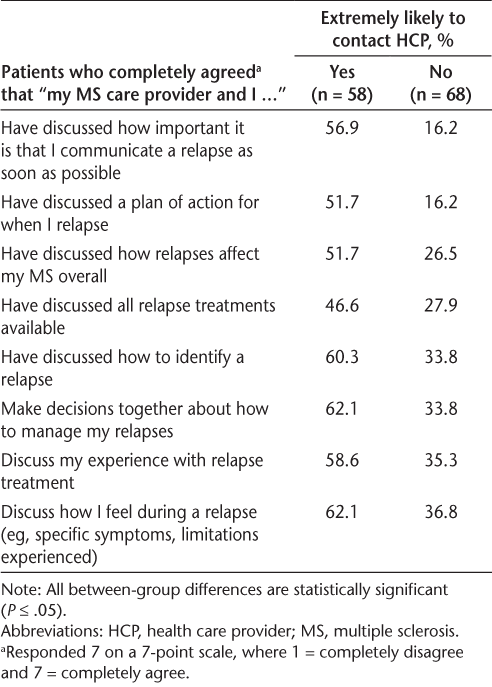

Patients who were extremely likely to contact their HCP during a relapse (n = 58) were significantly more likely than all other patients (n = 68) to report having had previous discussions with their HCP regarding relapse management (Table 1). For example, these patients were more likely to agree that their HCP had discussed the importance of early communication of relapse symptoms, how to proactively manage a relapse, and available relapse treatment options. Of patients who were extremely likely to contact their HCP during a relapse, 69.0% were extremely likely to accept their HCP’s recommendation for prescription medication or a procedure to treat their relapse compared with 42.6% of all other patients (P ≤ .05). More than half (56.9%) of patients who were extremely likely to contact their HCP had one relapse or less per year compared with 42.6% of those not extremely likely to contact their HCP (difference not statistically significant).

Likelihood of contacting HCP during a relapse based on previous communications with HCP about relapse management (N = 126)

In the logistic regression analysis (Table S4), two items best predicted a patient’s being extremely likely to contact their HCP during a relapse: reporting that they and their HCP had discussed the importance of communicating a relapse as soon as possible (predictive index, 0.82) and willingness to accept their HCP’s recommendation for medication or a procedure to treat their relapse (predictive index, 0.79). The final logistic regression model with these two predictors had an R2 of 0.139. Although not included in the final model, the other seven types of previous communication with HCPs about relapse management (Table 1) had predictive index values of 0.48 to 0.67. All other items tested, including measures of overall relationship with the HCP, frequency of appointments with the HCP, age, type of health insurance, and Patient-Determined Disease Steps scale level, had predictive index values of 0.40 or less (Table S4).

Patients who were not at all, slightly, or moderately likely to contact their HCP during a relapse (n = 39) most commonly stated the following reasons for not making contact: “My relapses are not severe enough” (46.2%), “I don’t really know if/when I should contact my doctor during a relapse” (33.3%), and “I haven’t found a treatment that works well to resolve my relapses” (17.9%).

Discussion

Factors that influence patients’ engagement with their HCPs during an MS relapse are not well understood. We found that patients were most likely to contact their MS HCP during a severe relapse and least likely during a mild relapse. In regression analysis, the HCP’s previous specific discussions with the patient about relapse management, along with the patient’s willingness to accept the HCP’s recommendation for relapse treatment, were the best predictors of the patient being likely to contact the HCP during relapse.

Similar to the earlier MSIA 2017 survey,14 less than half of the patients in this survey (46%) were extremely likely to contact their MS HCP during a relapse, and patients were more likely to contact them during severe relapses. In both studies, the quality of interaction between patient and HCP was a predictor of the patient contacting the HCP during a relapse. In the earlier MSIA study, compared with patients who were less likely to engage their HCP, patients who were more likely to contact their HCP more often reported that during the interaction at the time of relapse their HCP spoke with them about symptoms and severity of relapse as well as treatments for relapse and their effectiveness and also asked about the patient’s satisfaction with relapse treatment.14 In the present study, we found that previous conversations among patients and HCPs about management of relapses were the strongest predictors of whether a patient would contact their HCP during a relapse. The single most important predictor of a patient being likely to contact their HCP during a relapse was that the HCP had previously discussed the importance of communicating a relapse as soon as possible.

The present findings are consistent with previous studies in emphasizing the importance of a strong relationship, open dialogue, and shared decision making between patients with MS and their HCPs.16–19 The HCP’s patient education about early identification and reporting of relapses, along with interactive discussions about a plan of action and available treatment options, increased the likelihood of patient contact with the HCP and proactive disease management during a relapse. The HCP’s discussion of individual relapse experiences and differentiation of mild, moderate, and severe relapse symptoms also contributed to patient understanding of when to seek evaluation or treatment.

Underreporting of relapse experiences may, over time, erode the patient-HCP relationship, culminating in decreased patient satisfaction and poorer health outcomes. In contrast, patients’ willingness to contact their HCP during a relapse allows the HCP to assess the severity of the relapse and offer appropriate treatment options. Successful treatment of relapses may, in turn, enhance the patient-HCP relationship because patients are able to take better control of their disease management.5 Finally, in the overall scheme of care, HCP awareness of the occurrence, frequency, and severity of a patient’s relapses can inform decision making about ongoing DMT therapy.

In the absence of a clinical definition of relapse severity, this study also provides insight into the patient perspective on relapse severity and the symptoms patients associate with each level of severity (mild, moderate, or severe). Patients reported more symptoms associated with increasingly severe relapses. In particular, the self-reported incidence of walking difficulties, vision difficulties, and spasticity increased markedly with more severe relapses.

There were limitations to this study. As with any survey study, the study population is a convenience sample, and findings may not be generalizable to the full population of patients with MS. For example, almost 90% of the participants in this survey were White. The relatively small sample size in this study also limits the ability to generalize. The original intent of the survey was to compare patients treated with RCI and IV corticosteroids. Therefore, patients who had received only oral corticosteroids for treatment of relapses were not included. This may have resulted in the exclusion of a cohort of patients with mild-to-moderate flares managed on an outpatient basis. In addition, some patients who had received RCI got reminders of the survey invitation, whereas patients who had received IV corticosteroids did not get survey reminders. This may have affected the present findings if early versus late survey participants varied in their response patterns.

The validity of self-report measures is limited by recall bias and respondents’ incomplete awareness of their own motivations. In this study, respondents were subject to a relatively long recall period (2 years). Patients may not have accurately characterized their past relapses, including occurrence, severity, and symptoms. However, the relapse and treatment experiences (injection vs infusion) are likely to be more notable (and memorable) to patients compared with more standard or oral treatments, and, therefore, it is reasonable to expect fairly accurate recall of these episodes. Finally, most survey items were not previously validated, so interpretation of the findings relies on the face validity of these items.

In conclusion, this study highlights the association between HCPs’ advance discussions with patients with MS about relapse and patients’ subsequent likelihood of contacting their MS HCPs for appropriate relapse management. Further insights are needed into the behavior and assumptions of patients when they experience a relapse and how they can best engage their HCPs.

PRACTICE POINTS

In this survey, less than half of the patients with MS were extremely likely to contact their MS health care provider (HCP) during a relapse.

The best predictor of a patient contacting their HCP during a relapse was that the HCP had previously discussed with the patient how important it is that they communicate a relapse as soon as possible.

The findings highlight the importance of HCPs proactively communicating with patients who have MS about management of relapses.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Courtney Robertson of Health Union and Dr Bridget Bly for assistance with survey design and analysis. Editorial support for this article was provided by Lisa Baker, PhD, and Melissa L. Bogen, ELS, of the Global Outcomes Group.

References

Goodin DS, Reder AT, Bermel RA, . Relapses in multiple sclerosis: relationship to disability. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016; 6: 10– 20.

Kalincik T. Multiple sclerosis relapses: epidemiology, outcomes and management: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 2015; 44: 199– 214.

Treating multiple sclerosis relapses. Multiple Sclerosis Association of America. Published 2019. Accessed October 1, 2019. https://mymsaa.org/ms-information/treatments/relapses

Stoppe M, Busch M, Krizek L, Then Bergh F. Outcome of MS relapses in the era of disease-modifying therapy. BMC Neurol. 2017; 17: 151.

Berkovich R. Treatment of acute relapses in multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2013; 10: 97– 105.

Duddy M, Lee M, Pearson O, . The UK patient experience of relapse in multiple sclerosis treated with first disease modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014; 3: 450– 456.

Nickerson M, Cofield SS, Tyry T, Salter AR, Cutter GR, Marrie RA. Impact of multiple sclerosis relapse: the NARCOMS participant perspective. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015; 4: 234– 240.

Managing relapses. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Published 2019. Accessed October 1, 2019. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Treating-MS/Managing-Relapses

Nazareth T, Datar M, Yu TC. Treatment effectiveness for resolution of multiple sclerosis relapse in a US health plan population. Neurol Ther. 2019; 8: 383– 395.

Sellebjerg F, Barnes D, Filippini G, . EFNS guideline on treatment of multiple sclerosis relapses: report of an EFNS task force on treatment of multiple sclerosis relapses. Eur J Neurol. 2005; 12: 939– 946.

Acthar Gel. Package insert. Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals; 2019.

Costello J, Njue A, Lyall M, . Efficacy, safety, and quality-of-life of treatments for acute relapses of multiple sclerosis: results from a literature review of randomized controlled trials. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2019; 9: 55– 78.

Nickerson M, Marrie RA. The multiple sclerosis relapse experience: patient-reported outcomes from the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry. BMC Neurol. 2013; 13: 119.

Nazareth TA, Rava AR, Polyakov JL, . Relapse prevalence, symptoms, and health care engagement: patient insights from the Multiple Sclerosis in America 2017 survey. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018; 26: 219– 234.

Hohol MJ, Orav EJ, Weiner HL. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a simple approach to evaluate disease progression. Neurology. 1995; 45: 251– 255.

Lugaresi A, Ziemssen T, Oreja-Guevara C, Thomas D, Verdun E. Improving patient-physician dialog: commentary on the results of the MS Choices survey. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012; 6: 143– 152.

Riñon A, Buch M, Holley D, Verdun E. The MS Choices Survey: findings of a study assessing physician and patient perspectives on living with and managing multiple sclerosis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011; 5: 629– 643.

Tintoré M, Alexander M, Costello K, . The state of multiple sclerosis: current insight into the patient/health care provider relationship, treatment challenges, and satisfaction. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016; 11: 33– 45.

Schlegel V, Leray E. From medical prescription to patient compliance: a qualitative insight into the neurologist-patient relationship in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018; 20: 279– 286.