Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Symptomatic Management of Multiple Sclerosis–Associated Tremor Among Participants in the NARCOMS Registry

Background: Tremor affects 25% to 58% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) and is associated with poor prognosis and increased disability. MS-related tremor is difficult to treat, and data regarding patient-reported characterization and response to treatment are limited. We describe the symptomatic treatment of tremor in 508 enrollees in the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry who self-reported tremor.

Methods: From 777 surveys sent to NARCOMS participants who indicated mild or greater tremor using the Tremor and Coordination Scale, we compiled data regarding disability, tremor severity, symptomatic medication use, and reported response to medications.

Results: Symptomatic medications reported to reduce tremor were used by 238 respondents (46.9%). Symptomatic medication use was associated with increased rates of unemployment and disability, and many other characteristics were similar between groups. Symptomatic drug use was more likely in participants reporting moderate (53.9%) or severe (51.3%) tremor than in those with mild (36.6%) or totally disabling (35.0%) tremor. This disparity held true across multiple tremor severity scores. The most commonly used drug classes were anticonvulsants (50.8%) and benzodiazepines (46.2%), with gabapentin and clonazepam used most often in their respective classes.

Conclusions: Tremor in MS remains poorly treated; less than half of the participants reported benefit from symptomatic medications. Patients with moderate-to-severe tremor are more likely to report tremor benefit than are those with mild or disabling tremor. γ-Aminobutyric acid–active medications were most commonly reported as beneficial.

Despite years of treatment advances in immunomodulation, patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) continue to grapple daily with multiple disabling symptoms. Many of these symptoms directly affect patients' functional status and quality of life. The approval in recent years of drugs designed to lessen the impact of MS symptoms, such as dalfampridine for gait impairment1 and dextromethorphan/quinidine for pseudobulbar affect,2 have improved quality of life for some patients. However, for most MS symptoms, treatment is accomplished using drugs in an off-label manner, with varying degrees of success. Tremor associated with cerebellar ataxia is among the more difficult MS symptoms to treat.

An estimated 25%3 to 58%4 of patients with MS experience tremor, and moderate-to-severe tremor may occur in up to 15% of patients.5 Owing to its common involvement of the upper extremities and its effects on gait and balance, the presence of tremor confers a higher rate of neurologic impairment relative to other MS symptoms.4 MS tremor often involves components of cerebellar intention tremor and postural tremor, and it is often associated with speech dysarthria as well. It may present with features of a rubral or Holme's tremor from midbrain lesions that can have profoundly disabling velocity and amplitude. Indeed, others have reported that the presence of any MS tremor increases the likelihood of early retirement or unemployment, and at an earlier age compared with other patients with MS.3

Despite the functional limitations caused by MS tremor, relatively few studies have described the effects of medication on reducing tremor severity. Most drugs studied for their ability to lessen the effect of tremor have shown either negative results (eg, cannabis6 7 and propranolol8) or possible benefit that was not replicated (eg, levetiracetam9 10 and ondansetron11 12) or were poorly tolerated (isoniazid13–16). However, negative studies do not preclude the possibility that available drugs may provide a measure of relief from tremor symptoms for some patients.

In this report, we describe the results of a survey conducted using the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) patient registry, which includes more than 37,000 North Americans living with MS. As part of the survey, we asked respondents who self-identified as having tremor to report whether they experienced tremor reduction from symptomatic medications. In addition, we report which symptomatic medications were most often credited with reducing symptom severity. In light of previously published data, we expected to find that symptomatic medications offered modest reported benefit and that patients with more severe tremor would be more likely to report symptomatic medication use and benefit.

Materials and Methods

Respondents with tremor and ataxia were identified by their responses on the Tremor and Coordination Scale (TACS)17 on NARCOMS semiannual update surveys. The TACS is a tremor severity scale in MS that was previously validated against the cerebellar Functional System Score in the Expanded Disability Status Scale and the Nine-Hole Peg Test in an article by Marrie et al.17 On the TACS, respondents describe their symptoms based on a scale from 0 to 5 (0 represents absent tremor; 1, minimal tremor that does not cause functional impairment; 2, mild tremor; 3, moderate tremor; 4, severe tremor; and 5, totally disabling tremor). By definition, any score of 2 or greater indicates at least some functional impact by tremor or incoordination. For this study, only individuals indicating mild or greater tremor were invited to complete a supplemental survey. This approach limited the study population to those with functionally relevant tremor.

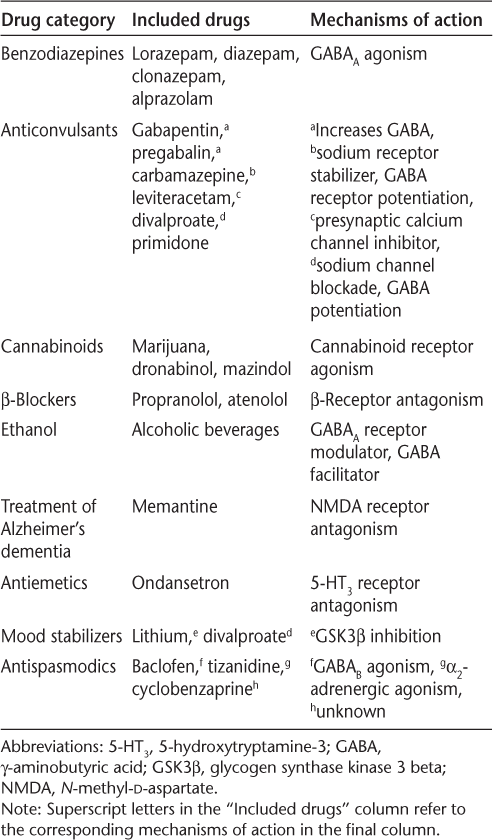

To assess the impact of tremor on daily function and quality of life, we designed a supplemental survey for NARCOMS registrants that included questions about symptomatic treatment of tremor with a range of commonly used medications (Table 1). Conversely, the survey also asked respondents to identify medications they were taking that worsened their tremor or coordination. The medication lists for both types of question were identical, and respondents were given a write-in option for treatments not included in the list. Write-in medications not included on the survey list were incorporated into the data set. Respondents could also indicate whether they had undergone surgical interventions (such as stereotactic brain surgery) to treat their tremor. Survey respondents were also asked to complete a series of scales assessing tremor severity, including the TACS, a visual analogue scale of tremor severity, and Archimedes' spirals, which were scored by blinded raters according to an established rating system.18

Categories of symptomatic medications used to reduce tremor severity

With University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board approval, we mailed surveys in March 2012 to 777 NARCOMS registrants who had indicated current use of an MS disease-modifying drug (DMD) and tremor of mild or greater severity on the TACS from a previous semiannual update. Current use of an MS DMD was required owing to a separate research question we were addressing in the survey, namely, whether certain DMDs are associated with tremor regression.19 Completed surveys were returned to NARCOMS and were compiled into a de-identified data set for analysis. Additional data, including demographic characteristics, a generic quality of life measure (the 12-item Short Form Health Status Survey [SF-12]), and Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS)20 scores, were extracted from NARCOMS semiannual surveys and included in the final data set. The PDDS is an ordinal patient-reported scale that is analogous to and correlates with the Expanded Disability Status Scale.

The survey results were used to perform a series of cross-sectional comparisons. In the first comparison, respondents who reported a symptomatic benefit from medications were compared with those who did not. Subsequently, users and nonusers were stratified and compared by tremor severity. Finally, for respondents who reported using symptomatic medications, the drug categories, drug names, and number of drugs taken per individual were compiled.

Owing to the cross-sectional nature of these data and the variation in disease duration and disability in this cohort, we used the Patient-Derived MS Severity Score (P-MSSS)21 to assign an overall MS disease severity score to each respondent. The P-MSSS adjusts disability (using the PDDS) for disease duration, allowing for cross-sectional comparisons of disease severity as opposed to current disability.

Statistical analysis was completed using JMP software, version 11.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Descriptive characteristics for both groups are reported as frequencies, means, and medians for nominal, continuous, and ordinal data, respectively. Differences between the groups were compared using χ2 tests for categorical data, t tests for continuous data, and Wilcoxon tests for ordinal data. Adjusted analyses were performed using a standard least-squares analysis.

Results

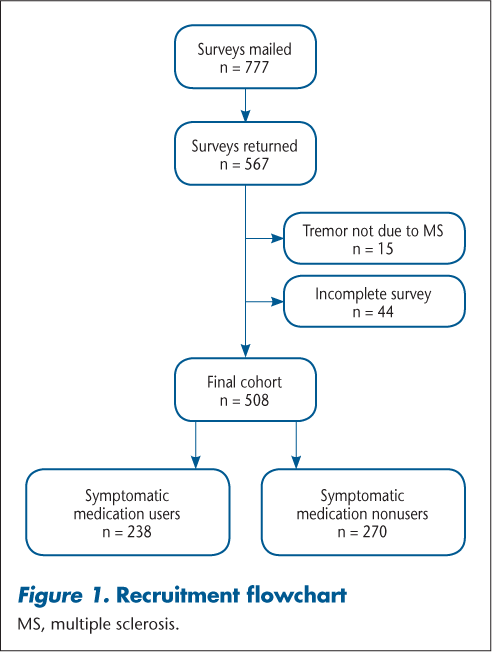

Surveys were returned by 567 participants, of which 508 were ultimately included in the analysis (Figure 1). Respondents were divided into two groups based on their “yes” or “no” response to the question: “Do you currently take any of the following medications to help with your tremor?” referring to the drugs listed in Table 1. Approximately half of the cohort (46.9%) reported taking a medication to reduce the severity of their tremor. Only 12 participants (2.4%) underwent surgical intervention to lessen their tremor severity: 7 taking symptomatic medications and 5 not taking symptomatic treatments. Twenty respondents (3.9%) reported taking a medication that worsened their tremor, 11 of whom also reported a symptomatic benefit from a different medication.

Recruitment flowchart

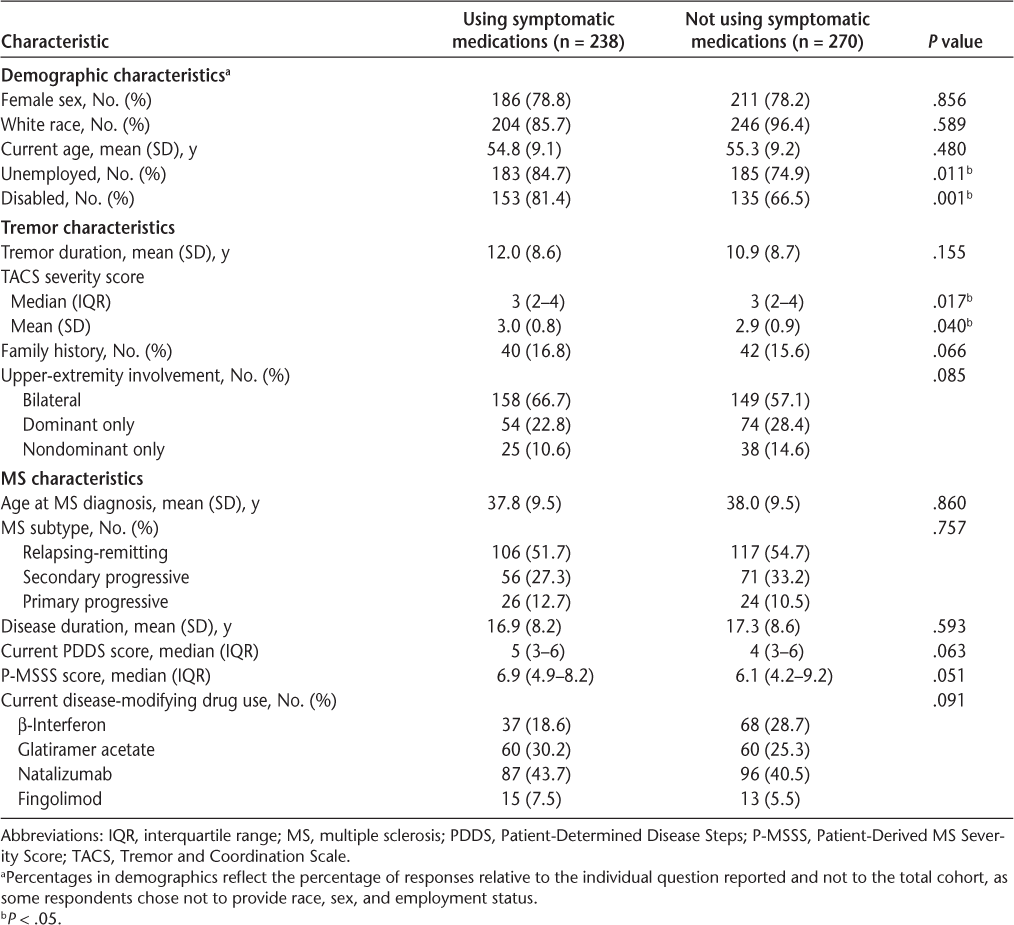

Demographic and Disease Characteristics

Comparing users and nonusers of symptomatic medications, the groups differed in a few key categories (Table 2). Users of symptomatic medications were significantly more likely to be unemployed or to report disability from work, but on other demographic variables, no differences were noted between the groups. With respect to tremor characteristics, a Wilcoxon test of tremor severity as measured by the TACS showed a significant difference between the groups; however, the magnitude of difference was small enough that the medians and interquartile ranges were the same for both groups. A test of the mean TACS score revealed a slight increase in TACS scores in the group using symptomatic medication, but with a mean between-group difference of only 0.1 points.

Tremor cohort characteristics

We also compared the MS characteristics between groups and found no significant differences in age at diagnosis, disease duration, MS subtype, or use of particular DMDs. Although there was a trend toward symptomatic medication users having more severe MS, as measured by both the PDDS and the P-MSSS scores, neither was significantly different from the scores of nonusers.

Tremor and MS Severity

Despite the paucity of distinguishing characteristics between users and nonusers of symptomatic medication, two points led us to consider in greater detail the relationship between tremor severity and symptomatic medication use: first, the higher rates of disability and unemployment in users of symptomatic therapy and, second, the consistency of a trend toward greater MS and tremor severity in medication users.

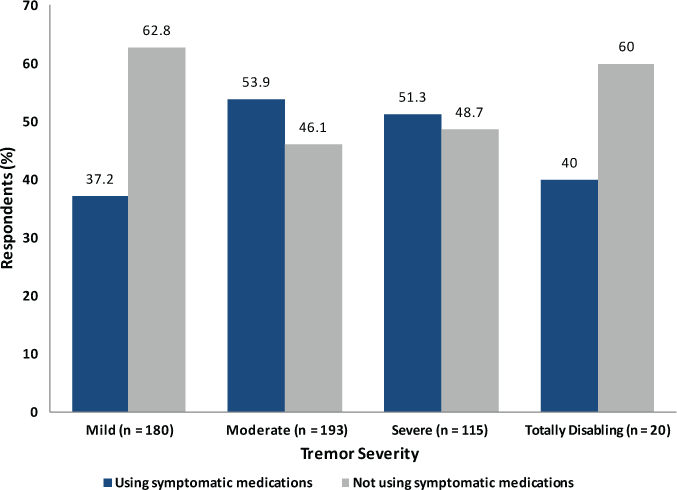

We first compared symptomatic medication use after stratifying by tremor severity as defined by TACS scores (Figure 2). In this comparison, we found that respondents with moderate (53.9%) or severe (51.3%) tremor were somewhat more likely than not to use symptomatic medications, whereas those with mild (37.2%) or totally disabling (40.0%) tremor were much less likely to use symptomatic medication. Thus, use of symptomatic medication was not evenly distributed across groups defined by tremor severity.

Symptomatic medication use by Tremor and Coordination Scale severity

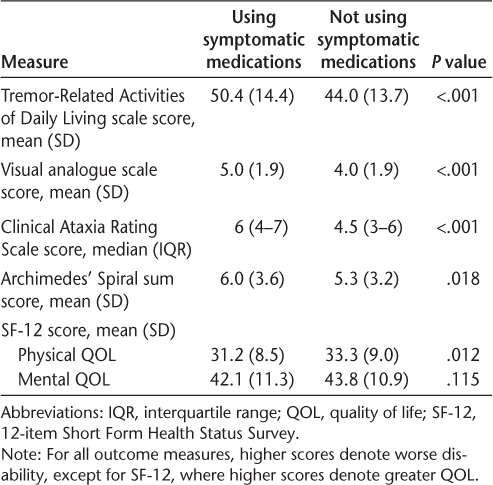

We next compared symptomatic medication use across a range of additional tremor severity measures, including the Tremor-Related Activities of Daily Living scale,22 which is based on a wide range of common daily activities; the Clinical Ataxia Rating Scale21; a visual analogue scale; and Archimedes' spirals,21 which were scored by blinded raters according to a published rating system. Unadjusted comparisons of symptomatic medication use by these measures are shown in Table 3. Tremor severity was worse in users of symptomatic medication across all these scales as well as the more generic overall physical quality of life measure using the SF-12. In contrast, a measure of mental quality of life using the SF-12 did not correlate with symptomatic medication use. After adjusting for TACS scores, the differences between the groups remained statistically significant, except for the physical quality of life measure (P = .079).

Use of symptomatic medications in relation to tremor severity and quality of life

Medications Used for Symptomatic Relief of Tremor

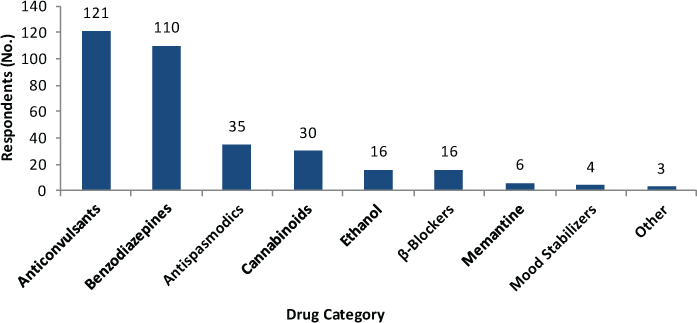

We next tabulated the medications (Table 1) identified by respondents as providing symptomatic relief from their tremor. Figure 3 illustrates the number of respondents reporting symptomatic benefit from each listed class of medication. Although most respondents (n = 154 of 238, 64.7%) used only one medication, 56 (23.5%) used two drugs and 28 (11.8%) used three or more drugs. The drug categories used most often to lessen tremor symptoms were anticonvulsants (50.8% of symptomatic medication users) and benzodiazepines (46.2%), with modest numbers of respondents also indicating benefit from antispasmodics (14.7%) and cannabinoids (12.6%).

Number of respondents using at least one medication reporting improved tremor by drug category

Among users of benzodiazepines, clonazepam was the most commonly reported beneficial drug (46% of benzodiazepine users), and among users of anticonvulsants, gabapentin was the most commonly cited drug (72% of users). Following gabapentin, only pregabalin was used in more than 10% of instances. Levetiracetam, which has been reported to be beneficial in at least one small trial of MS-associated tremor, was reported to be beneficial by only 2% of those using anticonvulsant medications. Among the antispasmodics, baclofen (68%) was the most commonly cited drug, and tizanidine (29%) and cyclobenzaprine (3%) were used less often.

Of those who used multiple drugs, most combined drugs from different therapeutic classes, although nine respondents reported using two anticonvulsants, and nine reported using two different benzodiazepines.

Of note, drugs commonly regarded as effective for suppressing essential tremor, such as primidone, β-blockers, and ethanol, were seldom cited as helpful in this cohort. In essential tremor, primidone and alcohol reduce tremor severity in as much as 72%23 and 74%24 of patients, respectively. In this cohort, only two respondents reported benefit from primidone, and 16 reported a benefit from ethanol.

Discussion

With a response rate of 73% and a total cohort of 567 in this cross-sectional study, the data presented are those of one of the largest cohorts published concerning tremor in MS. Although several clinical trials have reported the effects of individual drugs on MS-associated tremor, descriptive accounts of how MS tremor is approached in common clinical practice are lacking. A recently published study looked at the prevalence and characteristics of tremor in this population but did not discuss symptomatic management of tremor.25 The present study provides a cross-sectional account of how MS tremor is commonly managed in clinical practice, and we report which treatments patients view as beneficial.

Before discussing the medications of possible therapeutic benefit, we must acknowledge that these results reinforce the widespread impression that medical treatments for MS tremor are neither widely used nor perceived as especially beneficial. This treatment-refractive phenomenon likely stems from the fact that MS tremor is often related to components of cerebellar ataxia, spasticity, and other comorbidities. Although it is not surprising that patients with mild tremor are less likely to take symptomatic medications than patients with more severe tremor, it is perhaps noteworthy that of patients with moderate or severe tremor, only approximately half report deriving any benefit from tremor-suppressing medication. Among the small fraction of the cohort with totally disabling tremor, only a third of respondents took symptomatic medications, again implying a large unmet need for symptomatic treatments. Factors that could possibly explain this observation would be that patients with severe tremor are less likely to be offered treatment, are more refractive to treatment, experience intolerable adverse effects at increasing doses, or have abandoned using symptomatic treatments because of intolerance or lack of efficacy.

A second conclusion suggested by these data is that drugs that act on γ-aminobutyric acid receptors, or that increase γ-aminobutyric acid activity in the brain, constitute the preferred treatment approach for patients receiving symptomatic treatment. Unclear, however, is the mechanism by which these drugs may benefit those who are taking them. Because the drugs used by patients to lessen tremor are not indicated for that purpose, and because these same drugs are widely used to treat MS symptoms other than tremor, it is possible that the drugs' effects on tremor are indirect. For example, benzodiazepines are widely used as anxiolytics and to a lesser degree as antispasmodics. Thus, if anxiety worsens MS tremor, and if anxiety responds to benzodiazepines, using a drug such as clonazepam to reduce anxiety may also reduce the severity of tremor. In addition, note that drugs commonly used to treat essential tremor were infrequently used by this MS population, implying that they are less effective or underprescribed in this population. Primidone, β-blockers, and alcohol were among the least cited beneficial medications for treating MS-related tremor, an observation that, to our knowledge, has not been reported in the published literature. Lack of reported benefit from primidone is unexpected, considering recently published literature in MS tremor showing a clear benefit of primidone,26 and may show that prescribing patterns do not reflect the recent publications associated with MS tremor.

Note that these data were collected via a retrospective, patient-reported questionnaire and have substantial limitations. Data such as these are subject to recall bias and to the variation in treatment approaches of neurologists and other providers. Also, these results cannot account for the many nonpharmacologic factors that may influence tremor severity over time. The higher rates of medication use in disabled and unemployed participants, even with similar tremor severity, may hint at the importance of these nonpharmacologic factors. Furthermore, this survey relied on respondent impression to determine whether their medications were beneficial, and this study was not equipped to verify the accuracy of respondents' answers or to quantify the degree of improvement in each individual's tremor.

In addition, because this was a cross-sectional study, we cannot draw conclusions about effects of medications on tremor severity. We contend that those with more severe disease who are unable to work are more likely to seek relief through medications and that the benefit derived from those medications is insufficient to alleviate the functional limitations caused by the tremor and ataxia.

Last, the design of this study did not include outcomes that independently measure levels of stress or anxiety, which, in light of the high use rates of benzodiazepines and other central nervous system depressants, such as cannabinoids, might have been informative in suggesting whether alleviation of anxiety alone may have an independent effect on reducing tremor severity.

In conclusion, despite the design limitations of this study, these results clearly support the notion that tremor results in significant functional impairment in MS, that symptomatic medications for tremor are infrequently used and often inadequate, and that better treatment options for patients with MS constitutes an unmet need. Perhaps more optimistically, these results suggest that treatments that alleviate other symptoms common to MS, such as anxiety, spasticity, and pain, may also provide an avenue to better understanding and treating this most disabling and difficult-to-treat symptom.

PracticePoints

MS-related tremor confers substantial disability and continues to be a difficult symptom to treat.

Patients with moderate-to-severe tremor are more likely to report benefit from symptomatic medications than are those with mild or disabling tremor.

Medications that act on γ-aminobutyric acid pathways may be beneficial in treating MS-related tremor.

References

Goodman AD, Brown TR, Krupp LB, et al. Sustained-release oral fampridine in multiple sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:732–738.

Panitch HS, Thisted RA, Smith RA, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine for pseudobulbar affect in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:780–787.

Pittock S, McClelland R, Mayr W, et al. Prevalence of tremor in multiple sclerosis and associated disability in the Olmsted County population. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1482–1485.

Alusi SH, Worthington J, Glickman S, et al. A study of tremor in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2001;124:720–730.

Koch M, Mostert J, Heersema D, et al. Tremor in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254:133–145.

Zajicek J, Fox P, Sanders H, et al. Cannabinoids for treatment of spasticity and other symptoms related to multiple sclerosis (CAMS study): multicentre randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:1517–1526.

Fox P, Bain PG, Glickman S, Carroll C, Zajicek J. The effect of cannabis on tremor in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62:1105–1109.

Koller WC. Pharmacologic trials in the treatment of cerebellar tremor. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:280–281.

Striano P, Coppola A, Vacca G, et al. Levetiracetam for cerebellar tremor in multiple sclerosis: an open-label pilot tolerability and efficacy study. J Neurol. 2006;253:762–766.

Feys P, D'Hooghe MB, Nagels G, Helsen WF. The effect of levetiracetam on tremor severity and functionality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2009;15:371–378.

Rice GP, Lesaux J, Vandervoort P, Macewan L, Ebers GC. Ondansetron, a 5-HT3 antagonist, improves cerebellar tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:282–284.

Gbadamosi J, Buhmann C, Moench A, Heesen C. Failure of ondansetron in treating cerebellar tremor in MS patients: an open label pilot study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;104:308–311.

Morrow J, McDowell H, Ritchie C, Patterson V. Isoniazid and action tremor in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48:282–283.

Bozek CB, Kastrukoff LF, Wright JM, Perry TL, Larsen TA. A controlled trial of isoniazid therapy for action tremor in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 1987;234:36–39.

Hallett M, Lindsey JW, Adelstein BD, Riley PO. Controlled trial of isoniazid therapy for severe postural cerebellar tremor in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1985;35:1374–1377.

Duquette P, Pleines J, du Souich P. Isoniazid for tremor in multiple sclerosis: a controlled trial. Neurology. 1985;35:1772–1775.

Marrie RA, Goldman M. Validation of the NARCOMS Registry: Tremor and Coordination Scale. Int J MS Care. 2011;13:114–120.

Bain PG, Mally J, Gresty M, Findley LJ. Assessing the impact of essential tremor on upper limb function. J Neurology. 1993;241:54–61.

Rinker JR II, Salter AR, Cutter GR. Improvement of multiple sclerosis-associated tremor as a treatment effect of natalizumab. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3:505–512.

Learmonth YC, Motl RW, Sandroff BM, et al. Validation of patient determined disease steps (PDDS) scale scores in persons with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurology. 2013;13:37.

Kister I, Chamot E, Salter AR, et al. Disability in multiple sclerosis: a reference for patients and clinicians. Neurology. 2013;80:1018–1024.

Bain PG, Findley LJ. Assessing Tremor Severity. London, UK: Smith-Gordon and Co 1993:5–24.

Lou JS, Jankovic J. Essential tremor: clinical correlates in 350 patients. Neurology. 1991;41:234–238.

Koller WC, Busenbark K, Miner K; Essential Tremor Study Group. The relationship of essential tremor to other movement disorders: report on 678 patients. Ann Neurology. 1994;35:717–723.

Rinker JR II, Salter AR, Walker H, Amara A, Meador W, Cutter GR. Prevalence and characteristics of tremor in the NARCOMS multiple sclerosis registry: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006714.

Naderi F, Javadi SA, Motamedi M, Sahraian MA. The efficacy of primidone in reducing severe cerebellar tremors in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2012;35:224–226.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: The NARCOMS Registry is supported, in part, by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers and its Foundation. The survey was funded by Biogen Idec.