Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Stopping Disease-Modifying Therapy in Nonrelapsing Multiple Sclerosis

Background: Current disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are of benefit only in people with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (RMS). Thus, safely stopping DMTs in people with secondary progressive MS may be possible.

Methods: Two groups of patients with MS were studied. Group A consisted of 77 patients with secondary progressive MS and no evidence of acute central nervous system inflammation for 2 to 20 years. These patients were advised to stop DMTs. Group B consisted of 17 individuals with RMS who stopped DMTs on their own. Both groups were evaluated at treatment cessation and for a minimum of 1 year thereafter. Multiple variables were assessed to determine those that predicted recurrent acute disease.

Results: Nine patients in group A (11.7%) and ten patients in group B (58.8%) had recurrent acute disease, almost always within 1 to 2 years of stopping treatment. The only variable of significance in group A distinguishing stable and relapsing patients was age (P = .0003), with relapsing patients being younger. Group B patients were younger and had significantly lower Expanded Disability Status Scale scores than group A, with no significant differences in age between relapsed and stable patients.

Conclusions: The DMTs can be stopped safely in older patients with MS (≥7 decades) with no evidence of acute disease for 2 years or longer, with an almost 90% probability of remaining free of acute recurrence. The high proportion of untreated patients with RMS experiencing recurrent acute disease is consistent with published data.

The introduction of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for multiple sclerosis (MS) in the 1990s dramatically changed the treatment paradigm for relapsing forms of MS (RMS). During the next several decades, the number of DMTs increased, but all were directed at RMS, and trials attempting to show benefit for progressive forms of disease had negative results.1 2

In most people with RMS, patterns of disease change over time. Acute inflammatory changes, manifested as new lesions on central nervous system (CNS) magnetic resonance images (MRIs) or as clinical relapses, decrease, with an associated decrease in acute inflammation pathologically.3 Thus, there may come a time when an individual's disease no longer requires medication to control acute inflammation. When that point is reached, stopping therapy with medications that are expensive and potentially toxic should be considered. Lonergan et al.4 addressed this concept, but no conclusions could be drawn regarding when to discontinue treatment. Several articles have demonstrated acute disease recurrence on stopping DMTs.5 6 Patients in these studies were younger (mean ages in the fifth decade), with only 1 year of treatment in the article by Wu et al.6 and only 1 year of no relapses in the article by Fox et al.5 Again, no data were presented as to when one could safely discontinue DMTs in individuals with nonrelapsing disease. To address this issue, we initiated this prospective study.

Methods

Patients

All the patients were under the care of the author, met the criteria for clinically definite MS,7 and initially had RMS. Details of this study were submitted to the institutional review board of North Memorial Medical Center (Robbinsdale, MN) for review. The board determined that no review was needed because the data in this study were obtained as part of the standard care of patients, all of whom had signed agreements to be cared for by the author.

Two groups of patients were studied. Group A consisted of 77 patients with previous RMS but no clinical or imaging evidence of acute CNS inflammation for 2 to 20 years. These patients were advised to stop DMTs. Group B consisted of 17 individuals with RMS, 16 of whom stopped DMTs on their own and one who stopped due to loss of insurance. Both groups underwent clinical and CNS imaging evaluations at treatment cessation and for a minimum of 1 year thereafter. Multiple variables were assessed to determine those that predicted recurrent acute disease.

Annual MRIs were obtained in 93% of the patients; repeated MRIs were not obtained in the remaining 7% due to the severity of a person's disability or unaffordable costs.

Criteria for Acute Disease Recurrence

The presence of acute disease recurrence required objective evidence of change, either on physical examinations, all performed by the author, or on contrast-enhanced CNS MRIs. Acute clinical relapses were defined as either the appearance of new neurologic symptoms compatible with MS or a worsening of previous symptoms, persisting for more than 24 hours, in the absence of fevers, infections, or other stressors (eg, sleep deprivation, medication adverse effects). Patients had complete neurologic examinations at those times and also had concurrent CNS MRIs. All the MRIs were performed using the same 1.5-T machine, with and without contrast, and were compared and read by the same group of neuroradiologists. In the absence of clinical changes, any new, expanding, or contrast-enhancing T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery lesions on MRIs were considered evidence of new, acute inflammatory disease. All patients with recurrent disease were offered the opportunity to restart DMT, and almost all did.

Statistical Analyses

Data were entered into a spreadsheet program (Microsoft Excel; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). Statistical analyses were performed by Dr. Gary Cutter (professor of biostatistics, University of Alabama, School of Public Health, Birmingham, AL) using the statistical software of the application. Differences between and within groups were calculated using the Wilcoxon two-sample test, the NPAR1WAY procedure (analysis of variance), and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Variables compared were age at time of change of DMT, time on DMT, time off DMT, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores of stable and worsened patients, and ages of stable versus worsened patients. Variations in DMTs used were not studied owing to their great variability, but none of the patients were receiving oral or intravenous DMTs.

Results

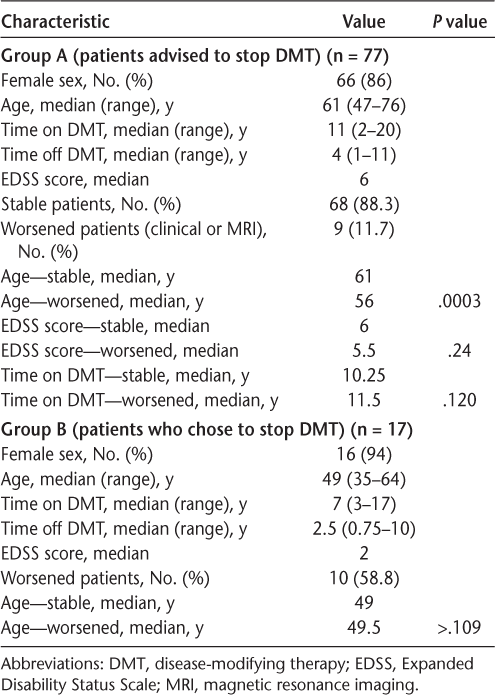

The results are summarized in Table 1. Nine patients in group A (11.7%) and ten patients in group B (58.8%) had recurrence of acute disease, almost always within 1 to 2 years of stopping treatment. Four of the nine patients in group A had a clinical change, in addition to the appearance of new lesions on CNS MRIs. The other five individuals were clinically stable or slowly progressive but had new lesions on their MRIs.

Results in study groups A and B

In group A, the only variable that differed significantly between stable patients and those with recurrent acute disease was age (the median age of stable patients was 61 years and of relapsing patients was 56 years; P = .0003) (Table 1). Differences in degrees of disability (EDSS scores) were not noted in worsened and stable populations (Table 1). The EDSS scores ranged from 1.5 to 8, with a median EDSS score in stable patients of 6 and in relapsing patients of 5.5 (P = .24).

Group B patients overall were younger than group A patients (median age of 49 years vs. 61 years; P < .0001). No significant differences were noted in the ages of stable and relapsing group B patients, but relapsing group B patients were significantly younger than relapsing group A patients (median age of 49.5 years vs. 56 years; P = .008) and had a significantly lower median EDSS score (2 vs. 5.5; P = .005).

Discussion

These findings suggest that older individuals, in their seventh or greater decades of life, with no clinical or MRI evidence of RMS for 2 years or more can safely stop DMT with an almost 90% chance of nonrecurrence of acute inflammation. Because choosing to stop DMT was voluntary, the previous interpretation is based on the assumption that patients advised to stop DMT but who chose to continue treatment would have responded in a similar manner to those agreeing to stop treatment. The validity of this assumption is not known.

Although there was a risk of acute disease recurrence in the group A population, the risk was small. When recurrence occurred, it did so within a relatively short time, usually within 1 to 2 years after treatment cessation. Of the 19 patients in groups A and B who experienced clinical or MRI relapses, only three (17%) experienced recurrent acute disease more than 2 years after stopping therapy (2.5, 3.5, and 7 years). The EDSS score at the time of treatment cessation did not predict subsequent disease quiescence (Table 1). Indeed, one younger patient, age 53 years, in group A with an EDSS score of 8 developed new brain lesions on MRI within 18 months of stopping DMT.

The present data are consistent with two recently published articles. The article by Rotstein et al.8 characterized a population of patients with RMS with no evidence of relapsing disease for varying periods. Although most patients had some evidence of disease recurrence, either clinically or on CNS MRIs, during the 7 years of study, those with no evidence of disease activity for 2 years or more had a predictive value of 78.3% of remaining free of subsequent disease progression, a value slightly lower than noted in the present study but supporting the concept that in older persons with long-term acute disease quiescence, DMT may not be needed. Paz Soldan et al.9 studied patients with varying forms of progressive MS, both primary progressive MS and secondary progressive MS, in terms of the effects of relapses on disease progression. Their data suggested that after 5 years on DMT, or after age 55 years, the risk of relapses declined sufficiently that treatment could be stopped.

Multiple studies have shown that in people with RMS, numbers of relapses diminish over time, as do MRI manifestations of acute CNS inflammation (reviewed in two studies10 11). Pathologic studies also demonstrated that acute inflammatory changes are almost absent in older patients with MS at autopsy.3 Although acute inflammatory changes in MS are due mainly to CNS infiltration by lymphocytes and activation of astrocytes,12 13 the pathologic changes characteristic of nonrelapsing MS involve chronic activation of macrophages and microglial cells, with progressive axonal degeneration, both components of immune system activation not addressed by any of the current DMTs. These data support the concept that there may be a time in the disease course of some individuals with initially relapsing disease when treatment with current DMTs can safely be stopped.

Potential Flaws and Biases of the Study

Because the decision to stop DMT was voluntary, not all patients advised to do so chose this option. Thus, the data reflect only a subpopulation of individuals with nonrelapsing MS. The criteria for choosing to continue DMT varied, but most consisted of either not wanting to assume the potential risks of having recurrent disease or wanting to continue to feel active and empowered in controlling their illness. It is not known whether patients choosing to stop DMT are inherently different in their responses to stopping treatment from those choosing to continue treatment. Should there be a difference, which the author feels is unlikely, the results would be biased.

These data may be of value in allowing health-care providers caring for individuals with MS to decide when to stop long-term DMTs in an older subpopulation of their stable, nonrelapsing patients. However, stopping DMT in younger patients, even those with long-term control of their disease with therapy, carries a high risk of acute disease recurrence.

PracticePoints

We observed low recurrence (11.7%) of acute disease activity after discontinuation of disease-modifying therapy (DMT) in patients in the seventh or greater decade of life with nonrelapsing secondary progressive MS with no evidence of acute central nervous system inflammation for 2 or more years preceding cessation of DMT. The median time off DMT was 4 years.

Close to 60% of patients with relapsing forms of MS who opted to stop DMT on their own experienced a recurrence of acute disease activity within 2 years off therapy.

These findings from an MS clinical center suggest that it may be safe to discontinue currently available DMTs indicated for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS in older patients who are free of acute central nervous system inflammation for at least 2 years, although monitoring for new acute disease recurrence is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Dr. Gary Cutter, professor of biostatistics at the School of Public Health, University of Alabama, Birmingham, for his assistance in performing statistical analyses of many of the data presented.

References

La Mantia L, Vacchi L, Di Pietrantonj C, et al. Interferon beta for secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD005181.

Mantia LL, Vacchi L, Rovaris M, et al. Interferon beta for secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013; 84:420–426.

Frischer JM, Bramow S, Dal-Bianco A, et al. The relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brains. Brain. 2009; 132:1175–1189.

Lonergan R, Kinsella K, Duggan M, Jordan S, Hutchinson M, Tubridy N. Discontinuing disease-modifying therapy in progressive multiple sclerosis: can we stop what we have started? Mult Scler. 2009; 15:1528–1531.

Fox RJ, Cree BA, De Seze J, et al. MS disease activity in RESTORE: a randomized 24-week natalizumab treatment interruption study. Neurology. 2014; 82:1491–1498.

Wu X, Dastidar P, Kuusisto H, Ukkonen M, Huhtala H, Elovaara I. Increased disability and MRI lesions after discontinuation of IFN-beta-1a in secondary progressive MS. Acta Neurol Scand. 2005; 112:242–247.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011; 69:292–302.

Rotstein DL, Healy BC, Malik MT, Chitnis T, Weiner HL. Evaluation of no evidence of disease activity in a 7-year longitudinal multiple sclerosis cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2015; 72:152–158.

Paz Soldan MM, Novotna M, Abou Zeid N, et al. Relapses and disability accumulation in progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015; 84:81–88.

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:1502–1517.

Hafler DA. Multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2004; 113:788–794.

Bar-Or A. The immunology of multiple sclerosis. Semin Neurol. 2008; 28:29–45.

Steinman L. Immunology of relapse and remission in multiple sclerosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014; 32:257–281.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Birnbaum has received honoraria for serving on advisory boards for Biogen, Teva Neurosciences, Merck Serono, Genzyme, and Accordis; has been a member of the speakers' bureau for Teva Neurosciences; and receives research support from Biogen, Genzyme, Hoffman-LaRoche, Biorasi, and Sun Pharmaceuticals.