Practice Points

- Mississippians with multiple sclerosis (MS) reported a wide range of social determinants of health (SDOH), ranging up to 9 SDOH for a single person, including factors not discussed in clinic, such as exposure to crime and violence, clean water access, and community isolation.

- MS diagnosis was the time point when participants identified their SDOH as most salient, particularly among Black participants.

- Interventions such as patient-navigation programs, transportation vouchers, and expanding teleneurology access may address some of the SDOH reported in locations like Jackson, Mississippi.

There are multiple social determinants of health (SDOH) that may influence the experience of people with multiple sclerosis (MS), but these have been largely understudied.1,2 This is particularly true in populations that experience the highest number of SDOH. Mississippi is a southeastern US state with a population of 2.94 million people.2 The state ranks last or close to last in the US in terms of major disease and critical health outcomes.3 In 2023, 18.0% of Mississippi’s residents lived in poverty, 10.3% were without health coverage, 17.7% were disabled, 54.3% were employed, 0.2% of adults used public transit to go to work, and 25.5% held a bachelor’s degree or higher.4 Mississippi’s population is 58.7% White, 37.8% Black or African American, and 3.6% Hispanic.4,5 Life expectancy in Mississippi was recorded as the lowest in the country at 70.9 years, compared with the national average of 76.4 years in 2021.5 Jackson, the state’s capital and most populous city, exemplifies these challenges. The greater Jackson metropolitan area was home to 610,257 residents in 2023, accounting for approximately one-fifth of the state’s population.6 The city of Jackson has experienced a series of major drinking water system failures, including loss of water pressure and unsafe water warnings in 2021 and 2022, which led to federally declared emergencies and long-term intervention by the US Environmental Protection Agency.7

The situation for people with MS is likely shaped by these broader SDOH and by a shortage of MS subspecialists in the Jackson area.1,2 In other studies, adverse SDOH (eg, lower income, underinsurance, and neighborhood deprivation) are recognized to disproportionately impact Black, Hispanic, and Latinx individuals with MS, leading to delayed care and worse MS outcomes.8-10 There is a lack of qualitative research examining how SDOH are experienced by people with MS in Mississippi, one of the poorest US states, and more importantly, how these SDOH may intersect and be modified.

To address this gap, 2 focus groups of adults with MS living in the Jackson metropolitan area were convened by neurologists. Our aims were to catalog the SDOH perceived as most influential by people living with MS, identify when in the disease course those SDOH were most acutely felt, and generate

patient-informed hypotheses for future interventions and study. In doing so, we sought to understand the realities of people with MS in an environment with a high potential for SDOH burden using their own words.

Methods

The study was approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) Ethics Board and exempted from the institutional review board of the Mass General Brigham (MGB).

Inclusion criteria for participants were adults with a neurologist-confirmed diagnosis of MS, current residents of Mississippi, and willingness to discuss their SDOH. Many participants were seen at the UMMC and had their medical records reviewed for MS diagnosis confirmation by a study physician at the UMMC (V.A., M.A.W.). Those who were not seen at the UMMC had the diagnostic confirmation of MS by a study physician (V.A.). To enroll in the study, it was not required that the MS participant be actively seeing a neurologist.

Recruitment was via e-mail; word of mouth through National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) peer support groups in Jackson, Mississippi; and direct referrals from a local MS neurologist at the UMMC (M.A.W.). Email messages were sent to NMSS chapter leaders, who forwarded the message to their members. There were no formal presentations of the study or publicly posted advertisements. Interested people with MS were encouraged to leave their name with a study physician for future callback and/or sign up via an online participant-facing portal (https://rally.partners.org) for study recruitment, which was run by the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Sampling was consecutive on a first-come, first-served basis.

Participants completed written informed consent remotely via Adobe—forms were emailed, reviewed by phone, signed in REDCap, and stored on a secure UMMC server. The survey11 was previously used for MS and SDOH focus groups conducted in Massachusetts by the primary author (F.J.M.) and refined for use by Mississippian participants by our team. Participants received the electronic questionnaire, querying their SDOH, as detailed by the Healthy People 2030 initiative,12 as well as their clinical MS history. All SDOH and clinical variables were patient reported.

Two focus groups were conducted online in August 2023 by UMMC and MGB neurologists via Zoom video software; they lasted approximately 2.5 hours each. Thirteen people with MS agreed to participate, and 11 participated (group 1, n = 6; group 2, n = 5). The 2 participants who did not come were not reachable to provide an explanation.

The 2 groups were offered on different dates to accommodate different schedules. The time of 4:00 pm was chosen after asking participants for availability preferences on both dates. This was to avoid missing too much work or delaying commutes home too long. If a participant could not attend the first group and still expressed interest in participating, they were invited to the second group. The participants were not deliberately divided. There was an overall balance between the 2 groups in terms of SDOH and overall participant numbers. Participants were invited to attend the focus groups online via Zoom or in person at the UMMC, where a study physician was present. Although parking reimbursement and refreshments were offered, no one chose to come in person, citing the summertime heat or the burden of transportation. Participants were paid $160 (US dollars) for their time.

Farrah Mateen (from MGH) is a neurologist with a PhD in public health and has conducted similar focus groups in MS and SDOH in Massachusetts.11 She led both study sessions with comoderator neurology resident Violet Awori (UMMC) using a semistructured discussion guide covering the US Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2030 SDOH domains.12 The MGH team organized logistics, facilitated questions, and provided compensation for participants.

The concept of SDOH in general was briefly discussed, after asking the group if they were familiar with the concept and if they found it relevant to their MS. Prompt questions in both focus groups were as follows: (1) What are the SDOH that are relevant to your MS? (2) How do these SDOH affect you? and (3) What would you like to see in your community to address these SDOH? If the discussion diverted from SDOH, the topic was probed for relevance, and if unrelated, the discussion was prompted by one of the SDOH variables on the Healthy People 2030 list.

Audio recordings and contemporaneous handwritten notes by the moderators captured all dialogue. Participants were encouraged to share freely and clarify one another’s comments.

Handwritten notes and transcripts were analyzed via an inductive thematic approach, in which codes and themes are derived directly from participants’ language rather than devised at the outset of the study design.13,14 Authors Mateen and Awori independently coded for SDOH relevance, compared interpretations, and reconciled discrepancies to compile comprehensive themes. Theme salience reflected both frequency of mention and apparent consensus among participants. No natural language processing or other software was used. Reporting follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research 32-item checklist15 (Table S1).

Results

Participant Characteristics

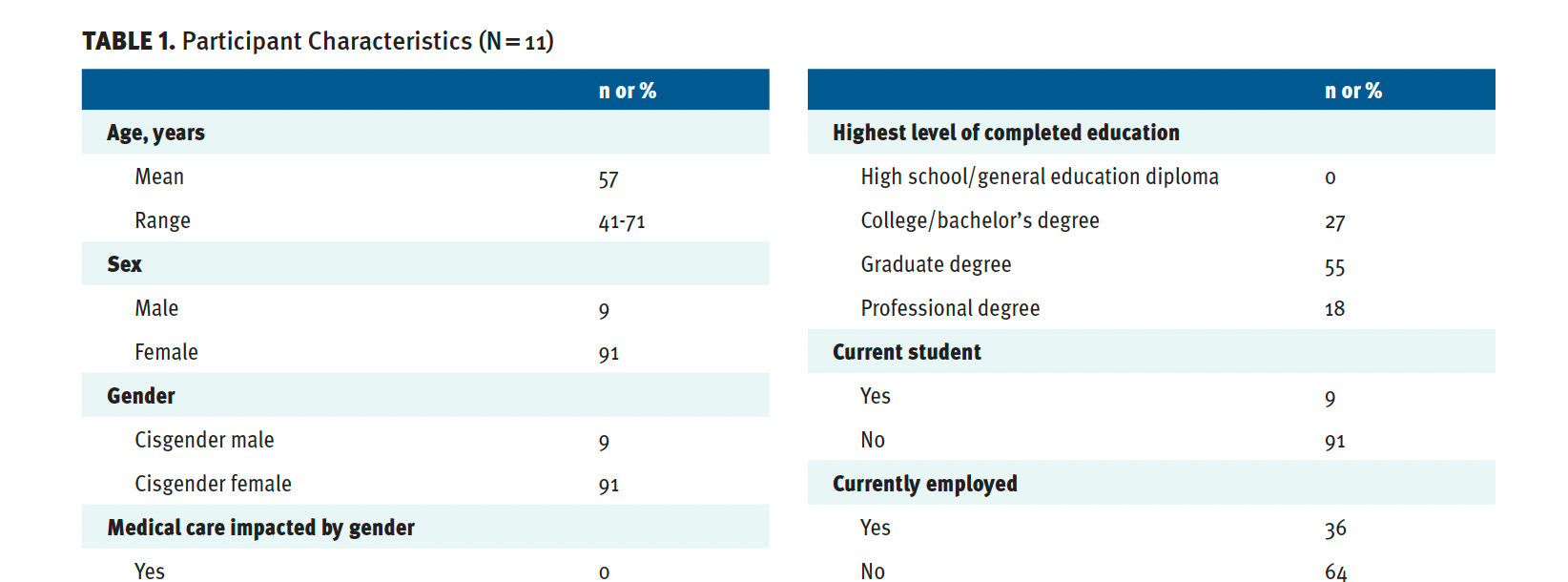

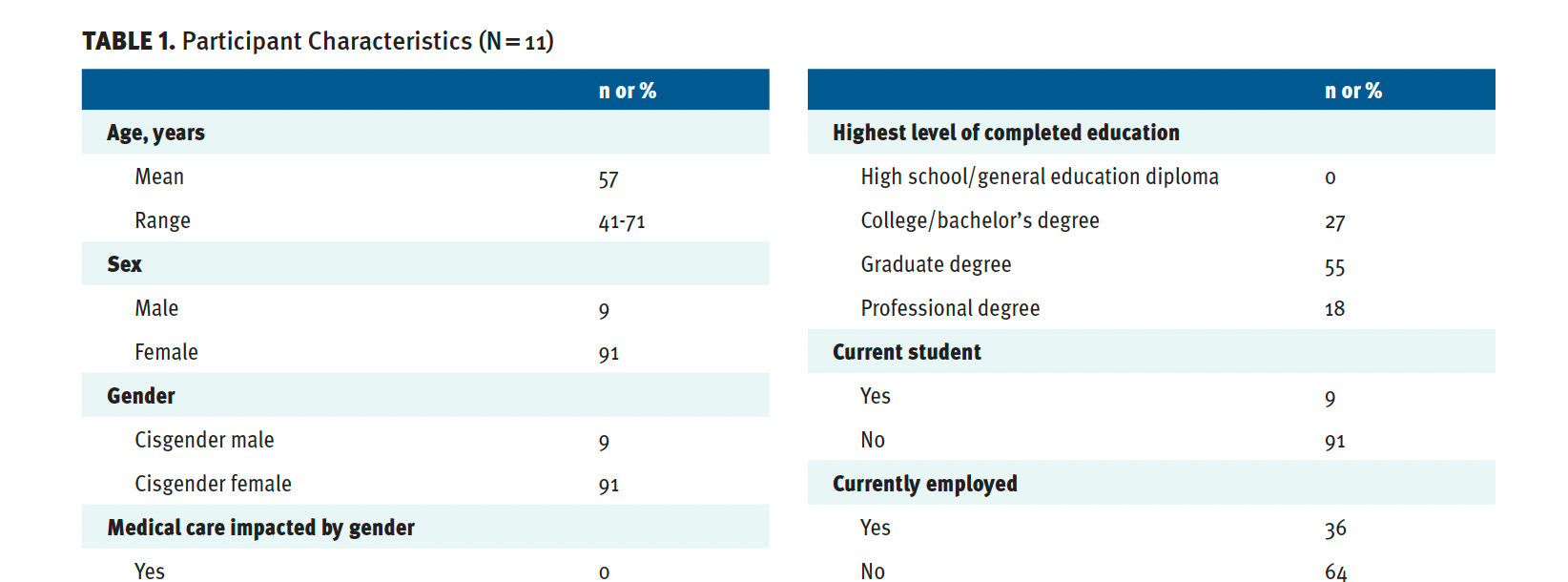

There were 11 participants; 9 (82%) had relapsing-remitting MS. Participants had a median of 6 (mean, 5) SDOH and were generally older (average age 57 years old) with an average MS disease duration of 17 years. Medication access was high, with 9 (82%) on a disease-modifying therapy (DMT). The group all had a bachelor’s degree or more education, was predominantly female (10 [92%] participants), and was mostly Black (64%) (Table 1). Participants scored high on having a history of personal or family member incarceration and perception of being treated with “less respect in a medical setting.” Job loss was reported by 36%. Housing insecurity was reported by 36%. Public health insurance was reported by 36%. Detailed participant responses related to the SDOH are presented in Table 1.

Participants recognized the effects of SDOH across the MS disease course but reported they were most relevant to the time of receiving an MS diagnosis. Additional relevance was noted in the contexts of access to ongoing neurologist’s care, access to a DMT, and access to MS research. Specific epochs in the MS experience and direct quotations related to MS diagnosis, ongoing care, and access to MS research are provided in Table 2.

All SDOH of relevance to participants, as ordered by the Healthy People initiative, were health care access and quality, education access and quality, social and community context, economic stability, and neighborhood and built environment. Within these, participants emphasized themes of race, education, occupation, transportation, disability services, crime and violence, water and food access, quality housing, and social isolation. Issues of lower salience were gender, income, ethnicity, and religious beliefs.

The 8 SDOH Emphasized by Participants

Race

Six participants believed that race was relevant to a delay in diagnosis and, at times, a misdiagnosis of MS. This mostly applied to Black participants. One said, “I was told, ‘It’s going to be a while to get you in.’ Me being a woman. Me being a Black had something to do with it.” Another added, “I had to make myself look bigger and stronger and louder to get what I need[ed].” Several participants expanded their experiences to their perceptions of Black individuals in the health care setting in general. “How many other Black people are told they are faking instead of sending them to a doctor who can figure it out?” They also emphasized historical injustices in the US, including, “As the Black community, we have been taught for years to keep our mouths shut” and “We were told for years to keep our mouths closed…taught not to tell our business.” Awareness in the African American/Black community was thought to be in need of strengthening overall, as stated by 2 participants: “I think a lot of African Americans don’t know about MS. I don’t think they realize the inflictions” and “I think people should be more informed in the Black community about MS. Before I had it, I didn’t know anything about it.”

Education

Three participants remarked that their educational levels were beyond a bachelor’s degree and helped them understand the MS diagnosis and treatment options; several felt the lack of high-quality schools in the state made them prone to vaccine-preventable diseases and fewer helpful health policies related to disability. One participant reported the need for more intervention in society, given the educational system in Mississippi: “The more disadvantaged you are, the better your education system should be. It inoculates us against fibs, misinformation, and BS.”

Water and Food

In Jackson, water security has been challenging. This was believed to pose a safety risk to MS patients on DMTs, due to water-borne infectious risk while being immunosuppressed, and also led to chronic stress, uncertainty, and negative mental health impacts. Four participants commented on the water quality. (1) “Continued water issues that we’ve had…. This affected whether or not we would have stress.” (2) “I go without water.” (3) “Water was out for about 3 weeks. I had a filter for my sink, on my shower also.” (4) “The water is bad. I just buy water.” Another participant linked her MS to the water supply: “How can you tell if you already have a condition if the water is making it worse?”

Three participants reported an unmet need to access fresh foods. One participant said, “It’s kind of hard to get organic food without paying an arm and a leg. And then, it doesn’t last long. It’s hard to find things you need.” As a solution, another participant proposed, “Funds [are needed] to pay for gardens in the community.”

Work and Occupation

MS had variable impacts on employment, with some participants retiring from their jobs for reasons unrelated to MS, some leaving a job due to MS and risk of opportunistic infections while on a DMT, some staying in a job to maintain insurance coverage for a DMT, some leaving due to decreased mobility and increased fatigue, some reducing their job demands to avoid job termination, and 3 never disclosing their MS diagnosis to their employers for fear of job termination. The heterogeneity of responses was notable on this SDOH, although most responses were negative. Two participants said, “MS lacks a lot of jobs I can perform and not lose my financial stability” and “If my employer finds out I need an assistive device, I will not be returning to work.” Others focused on the relationship between employment and health insurance: “My medication would not be covered without me working” and “DMTs have always been tied to your job. I have been without medication as a result. State insurance denied coverage of my medication. I got a flare.” Two participants left their jobs specifically because of MS. One said, “I lost my health insurance. I lost every friend I had over 20 years.” Another stated, “I had to leave my first career. There were ‘superbugs’ in the children’s hospital. It got to be too much.” One participant decided not to disclose her MS diagnosis to her employer, which resulted in no work accommodations: “I have not revealed I have MS to [my employer]. I took a lower position and shorter hours…to go to appointments and remove risks of being fired.” An outlying positive response was, “My first boss also had MS and helped me a lot.” Four participants wanted to work, but felt they could not. One said, “I would rather return to work. [We need] ways we can help companies understand how to keep people with MS employed.” Another said, “We need to advocate for organizations employing people with MS, working instead of forcing them to retire.”

Transportation and Disability Services

Participants reported that public transportation options were severely limited and did not cover the needs of people living in more rural areas. One woman said, “I cannot drive because of my MS. [This] exacerbates the social isolation and lack of access to everything: fresh food, recreation, social opportunities.” Another shared, “I would be everywhere if I didn’t have MS.”

Both focus groups reported that sidewalks are only sometimes present in Jackson. One participant reported having to engage in several years of litigation to obtain improved disability services in Jackson. He said, “I have been fussing and fighting for everything. I literally had to sue them in federal court…. Outside of Jackson, it didn’t catch on.” There were transportation limitations at one participant’s employer: “There was 1 elevator [at work]. I had to find the janitor to get the key…the stress of it.”

Three participants reported traveling out of state to get MS care (to Minnesota, Texas, and Florida). One participant noted, “I have a 6.5-hour drive [to get] Lemtrada.” Another said, “I spent a lot of money traveling back and forth” before discontinuing the DMT that required her to travel.

Crime, Violence, and Public Safety

Several participants reported a fear of gun violence and random violence, including robberies, vandalism, and assaults when at home, accessing medical care, and doing daily activities such as exercising or grocery shopping. There were multiple salient quotations from participants, and there was overall concordance on this determinant. (1) “I never carry a purse.” (2) “I keep my bus card and money and keys in different pockets.” (3) “I stay in the house.” (4) “I don’t go to the grocery store or go out after 5. I don’t go out or take a risk.” Specifically related to MS disability, participants said, (1) “Certain things I don’t, can’t, or don’t want to do anymore. I don’t go places because I can’t run anymore. I am in trouble because I fall.” (2) “MS has made a big difference in when I go out.” (3) “I am always looking around to see if someone is going to take advantage of me…. I watch where I go because I am slow.” One participant characterized crime as targeted at “people who are already vulnerable, who are sick, and too sick to fight them.”

Fear of crime and violence specifically affected access to neurological and general medical care: “[Can you] go safely to your doctor’s appointments? My coworkers have [had their] cars vandalized day or night, broken into, purses ripped off of them.” Another participant reported that if an appointment runs late, there are problems for her, “[At] 4:30, 5:00 pm, access [to the hospital parking lot] is cut off. They close the exits because of violence.”

People with MS also had general exposure to crime and violence. One woman reported, “My house was ransacked. They stole everything.” Another said, “I’ve been in my house 4 years. Someone got murdered across the street, another one. The kids are so disrespectful.” A third participant reported, “I’m waiting for the day to move…. The stress of it sometimes. It might be a gunshot in a panic. That can affect you. You wake up and hit the floor.” This was connected to “overall stress. Chronic stress does affect MS.” Violence also affected recreational and social gathering opportunities: “Holidays are just as bad. I found bullets in my yard.”

Neighborhood and Environment

Affordable housing options near grocery stores and public transport were considered very limited. One said, “We need more compact communities: sidewalks, buses, trains.” Another said, “I live in the country with no sidewalks.” A third reported, “I could have so much more freedom in Boston, more independence, and [I could] go and do more things, but I can never afford it.” A recurring theme among participants was summarized as “can’t get out of Jackson.” Specific to MS clinics, one woman shared a widely agreed-upon comment: “It’s more rural in Mississippi, so harder to get care.”

Most participants reside in flood-prone or climate-insecure areas. One reported, “I found a house, but it is in a flood zone. Is this the time when I am going to lose everything?” Several questioned environmental exposures in agricultural regions related to the onset of MS, such as growing up in cotton fields with pesticides. Said one, “I grew up in the Mississippi Delta, a low-income area.” Another relayed, “I think I have had several exposures that played into my disease. I also worked in the cotton fields for a summer and got sprayed.”

Social Isolation and Integration

Participants stated they are seen as physically slower, easily tired, and at risk of falls, making social integration less likely. Some reported feeling shunned from social events such as football games and family gatherings or stigmatized in public settings, such as church services, due to their fatigue and need for frequent breaks and assistance. One woman stated, “I fell in the middle of a Christmas parade. People stopped inviting me to different things.” Another said, “I lost all of my friends when I got sick, every one of them.” A third shared, “I was told, ‘We didn’t invite you to the cookout because we thought you would be tired.’”

The presence of MS community groups was considered beneficial. One participant claimed, “We are all friends [in the Central Mississippi MS support group]…. It helps to have a community of people that you can relate to.” Others emphasized close connections that were positive: “My friends understand. My kids understand,” and “My husband is really good at helping me.” Although religious groups were not prominently reported in these focus groups, one woman shared a positive impact: “When [I] got too hot in church, the pastor made me feel comfortable.”

Solutions

Multiple solutions were suggested by participants at the micro and macro levels of society. Participants suggested more education for their communities, physicians, and families, not just about MS, but also about disability. They noted that their diagnoses were made by people who were not neurologists, including a dentist, an occupational therapist, and friends. They found online resources helpful to combat a lack of access to early in-person expertise. Telemedicine across state lines was considered to be a viable solution but, at times, could feel isolating. From an employment perspective, participants proposed better job opportunities for people with MS, so they could remain financially stable as their disease evolved. Ideally, they suggested denser city structures to access food and clean water and maintain social lives. Public transportation and better accessibility for people with MS would be helpful to most participants. Many were loyal to their city and communities but desired better, broader educational systems as well. They believed they could contribute to research on DMTs and help answer epidemiological and etiological questions about what causes MS.

Discussion

Although limited in overall number, our participants with MS living in the Jackson metropolitan area of Mississippi identified multiple SDOH that are relevant to people with MS. The median number of SDOH per participant was high overall. These SDOH are contextualized by determinant to provide the lived experiences and voices of people with MS in a very geographically poor area in the US. Nonetheless, our participants were heterogeneous in the number of SDOH, including variations in income, sense of community, work, and access to MS care.

SDOH that are commonly recognized in Mississippi, such as limited public transit, intermittent water contamination, exposure to crime and violence, and rural residents’ isolation, were also noted among people with MS. At times, SDOH limited access to early MS diagnosis, specialty care, and MS research. The intersection of physical disabilities from MS with society was highlighted in terms of work and employment limitations, risk of exposure to violence, and limited access to fresh food. The intersection with mental health was prominent in terms of chronic stressors that occur with lower access to safe, affordable housing, communities, clean water, social support, and feeling believed. Higher educational achievement was thought to provide an advantage to people with MS, as it enabled them to learn about MS via independent research, separate from available health systems access. These findings align with a previous scoping review that identified themes across access to care and information, as well as practical barriers like financial strain, as recurrent themes among people with MS.16 Participant responses suggest that SDOH are not experienced as isolating barriers, but rather as mutually reinforcing pressures—compounding and shifting across the disease course in ways that shape not only access to MS care, but also one’s sense of agency and belonging in the health care system.

As of 2024, 1.11 million people in Mississippi—37.8% of the population—identify as Black/African American, a population that is recognized to have more SDOH and to be historically disadvantaged in the US.3 The impact of race as it may relate to all other SDOH deserves special mention, as Black participants with MS disproportionately reported a lack of community awareness of MS, disbelief of neurological symptoms that led to delayed diagnosis, and a general sense of not being taken as seriously by people in the medical system. A recent US focus group study concurs, finding that Black adults with MS have disparate care experiences compared with their White counterparts, more frequently citing barriers to affordable and accessible care, as well as racial discrimination.17 Similarly, a retrospective cohort study of 500 individuals with MS treated at a comprehensive center in Birmingham, Alabama—a setting that also reflects structural and regional challenges in the US South—found that Black patients had significantly higher odds of severe disability and requiring ambulatory assistance compared to their White counterparts, even after adjusting for demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic covariates.18 Together, these findings imply that in regions with high SDOH burden, race may further determine health care experiences and health outcomes, and they operate in more than 1 direction: as both an SDOH and as a compounding factor of other determinants.

One limitation of our study is a lack of objective disability metrics, which precluded correlating SDOH themes with disease severity. Additional limitations include our small sample size and overrepresentation of participants with higher education and higher income. People living with MS who are extremely underserved (eg, undiagnosed, outside of medical care) would represent a different group of patients than we have surveyed here. Our findings may not be generalizable to all people with MS in Mississippi, as many may be seen by clinicians who are not neurologists, be unaware of their diagnosis, be unable to access the internet, or elect not to participate in academic research. We provided payment for participation; however, some people may not have been able to leave work by late afternoon, when the groups were held. The choice of time of the focus groups was based on participants’ consensus. We may have missed specific eligible participants due to low literacy or mistrust of medical research. We had no Hispanic participants and did not recruit for the study with Spanish advertisements or to Spanish-speaking groups. This lack of participation may be expected given the low number of Hispanic residents in Mississippi (3.6%) and the small sample size of our study. We are unable to comment specifically on non-English speakers in the Jackson area in Mississippi.

Finally, the number of MS specialists in Mississippi is as low as is found in many lower-income countries and is not stable.19 Our efforts to identify more patients with MS were precluded by the out-migration of physicians from the state. Mississippi is an “MS specialist desert.”20 The number of MS specialists needed in any geography is not well defined, and the need is likely higher where there are more participants with many SDOH.

Conclusions

Our study results are meant to be formative for future studies on MS and SDOH. Given the scant literature on MS from Mississippi over recent decades and the risks of SDOH for people living with MS, we provide insights and patient perspectives on potentially modifiable nonmedical factors that could change a person’s MS disease experience.

To reach a wider group of people living with MS for future similar studies, primary care offices could be engaged. Additionally, meeting people in the community through advertisements on public transit (eg, buses), barber shops and salons, churches and other places of worship, grocery stores, casinos, pharmacies, recreation centers, and community kitchens could be considered. Successful recruitment and educational initiatives have been done in related diseases. For example, the Arkansas Minority Barber and Beauty Shop Health Initiative engaged more than 1800 people for cardiovascular disease screening in 14 counties over 3 years.21 Programs for cardiovascular disease screening and education have been successful in churches in Alabama.22 Some companies, such as Walmart, are developing services to advertise clinical research opportunities to underrepresented populations, particularly through their pharmaceutical care operations.23

Future work may combine qualitative inquiry with quantitative SDOH indices and disability scales. Given our findings, interventions such as patient-navigation programs, transportation vouchers, and expanding teleneurology access may address some but not all of the SDOH reported in areas like Mississippi.