Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Relational Satisfaction of Spousal/Partner Informal Caregivers of People with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Relational satisfaction of spousal/partner informal caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis (MS) is important for continued care and support. Previous studies have examined relational satisfaction in terms of well-being and quality of life of informal caregivers. Based on the Rusbult investment model, we directly studied the relational satisfaction of spousal/partner informal caregivers of individuals with MS. In doing so, we investigated possible effects that commitment to relationship, caregiving burden, and prorelational behavioral tendencies might have on relational satisfaction.

Methods:

Nine hundred nine adult spousal/partner informal caregivers of people with MS completed measures of relational satisfaction (Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale), commitment to relationship (15-item commitment measure), caregiving burden (Zarit Burden Interview), and prorelational behavioral tendencies (adapted Prosocial Tendencies Measure). Participants also provided demographic information (age, sex, duration and type of relationship [spouse, partner]).

Results:

Structural equation modeling highlighted commitment to the relationship as the strongest predictor of relational satisfaction. Caregiving burden was found to affect relational satisfaction directly and through commitment to relationship. Prorelational behavioral tendencies were found to affect less relational satisfaction.

Conclusions:

Commitment to relationship, namely, intent to persist, had the highest positive effect on satisfaction. Caregiving burden was found to have a two-way negative relationship to commitment to relationship. These findings suggest that specialists should enhance the intent-to-persist aspect of commitment because it seems to have an alleviating effect regarding caregiving burden (which itself negatively affects relational satisfaction).

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a common progressive neurologic disorder that is most likely to develop in young adults (men and women aged 20–40 years) and has an unpredictable course over time.1 2 Previous research has well documented the psychological consequences that people with MS undergo. Specifically, MS can have a considerable effect on the individual’s sense of self,3 a renewed sense of loss every time the individual experiences a new loss of function,4 problems with isolation, and a high prevalence of mood disorders (eg, depression, anxiety, fear, and anger).5 More important, people with MS tend to bring this psychological burden into the relationship with their spouse/partner, who, in many cases, is their informal caregiver.6 Thus, caregivers of individuals with MS should find a balance between these two roles. Also, they should cope with the serious changes that MS brings to their lives, to their relationship with their spouse/partner with MS, and to themselves. Research on this matter has mainly studied the well-being and quality of life of the informal caregivers of persons with MS, pointing out that spousal/partner caregivers are distressed, exhausted from the daily care and psychosocial support they give to their spouses/partners, and depressed, with a tendency to complain about the restraints in their social life and professional activity due to their increased caregiving duties.7 They also feel emotionally neglected and disappointed in their sexual life and regarding communication with their spouse/partner.8 Nevertheless, people with MS may need psychological support, and relative data indicate a positive relationship between the level of support provided by the spousal/partner informal caregiver and MS progression.9 At the same time, relational satisfaction is imperative for the spousal/partner informal caregiver to continue offering his or her services both physically and psychologically.10

According to the investment model, commitment to relationship is the element that keeps couples together, preserves the relationship, and protects relational satisfaction.11 Commitment refers to the sense of allegiance that a person develops toward the objects of his or her dependence and comprises three components: 1) intention to persist, 2) psychological attachment, and 3) long-term orientation. In studies regarding the general population, commitment has been found to be one of the strongest predictors of relational satisfaction and a key factor in transforming dependence from personal to relational, which, in turn, shifts costs and rewards appraisal from self to dyadic interest.12 Partners focus on common goals and common interests and receive satisfaction through the accomplishment of goals that, although they seem to serve the self-interest of one, are perceived as enhancing the interest of the relationship.13 The investment model of commitment extends this rationale by proposing that—apart from commitment—relational satisfaction in long-term relationships is associated with the performance of prorelational behaviors.14 The notion of prorelational behavior is a theoretical concept implying that, as in the case of prosocial behavior, a person benefits by someone else’s actions even if these actions may have a cost for the benefactor. In the case of prorelational behavior, a partner’s behavior might be seen as beneficial only for the other, while it would benefit the relationship by enhancing the dyadic interest. Note that only a few studies (eg, Collins et al,15 Neff and Karney16) have examined prorelational behavior, and they did so in terms of sensitivity and responsiveness to the partner’s needs.

Carlo and Randall17 empirically studied prosocial behavioral tendencies in adolescents and young adults and suggested a typology as follows: Altruism, selfless helping behavior that people tend to perform in cases in which their first priority is concern for the welfare of someone else, a behavior that sometimes incurs some kind of cost for the benefactor. Compliant, a tendency to help others not spontaneously but only when someone is asking or seeking help from a particular person. Emotional, helping others under emotionally evocative circumstances. Public, a tendency to help only in the presence of others in order for the helper to become appraised and respected by other people witnessing the person in need. Anonymous, a helping behavior that is performed by a person who wishes to remain unknown. Dire, helping behavior that is performed because the helper is strongly moved by the severe condition another person experiences, such as during a crisis; this could be useful for the study of prorelational behavior, especially in the case of a close relationship in which one of the two parts experiences a chronic illness and the other is not only the spouse/partner but also the informal caregiver.17

Existing data on relational satisfaction of spousal/partner caregivers of people with MS indicate a variety of variables that seem to play an important role in this matter. Specifically, it is well documented that caregiving burden directly affects the relational satisfaction of the caregiver. The higher the burden spousal/partner informal caregivers think that they are carrying, the lower their assessment of the level of relational satisfaction.18 Also, the type of relationship (partner or spouse) has been found to affect the level of the caregiver’s relational satisfaction. Informal caregivers of people with MS who were married to them reported lower levels of relational satisfaction and higher levels of stress and depression compared with informal caregivers of people with MS who were in a long-term relationship but not married to them.10 With respect to sex, male informal caregivers of people with MS have been found to feel more satisfied in their relationship with their spouse/partner compared with female informal caregivers.19 Finally, duration of the caregiving spousal/partner relationship and age of the informal caregiver were also highlighted as variables affecting relational satisfaction. Specifically, the longer the duration of the relationship and the greater the age, the lower the relational satisfaction and the higher the negative consequences (ie, depression, poor communication with the spouse/partner) from long-term caregiving.20

The present study has three goals: 1) to assess relational satisfaction, commitment to the relationship, and caregiving burden of spousal/partner informal caregivers of people with MS; 2) to investigate for significant differences between relational satisfaction and commitment to relationship, caregiving burden, type and duration of relationship, and sex and age of the caregiver; and 3) to explore the degree to which commitment to relationship, caregiving burden, and types of prorelational behavioral tendencies might affect the relational satisfaction of a spousal/partner informal caregiver of a person with MS.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

All the participants were Greek, were 18 years or older, and were either spouses or partners who have been informal care-givers of people with MS for at least 1 year. They participated in the survey voluntarily and provided informed consent. They did not receive payment for their participation. The first page of the questionnaire informed participants about the nature of the survey and assured them of the anonymity of their responses and the confidentiality of the information they were about to provide. All the study procedures and materials were reviewed and approved by the research ethics board of Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece, because the first author (M.T.) was, at that time, a postgraduate student at this university. Data collection was undertaken by this author with the supervision of the other two (E.L. and D.K.). We initially contacted the Hellenic Federation of People with MS and asked for their help in reaching the spousal/partner informal caregivers of people with MS. The Federation provided us with the mailing lists of people with MS in five major regions of Greece, and, thus, an e-mail was sent to them clearly indicating that this particular message was addressed specifically to their spouses/partners who at the same time were also their informal caregivers. The e-mail informed the spousal/partner informal caregivers about the nature and purpose of the survey and asked them to declare their intention to participate. Also, potential participants were informed about the two possible methods for completing the questionnaire (paper/pencil or online).

Measures

Note that for the following four measures, necessary adaptations in wording were made regarding relationship status (spouse/partner) and type of illness (MS). Participants also completed a short self-structured form regarding demographic information, such as sex, age, relationship type (spouse, partner with cohabitation, partner without cohabitation), and relationship duration.

Relational Satisfaction

We assessed relational quality via the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale,21 a three-item self-report instrument that measures marital quality. Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 6 (extremely satisfied). Total score ranged from 3 to 18, with higher scores indicating better relational quality. In the present study, Cronbach α = 0.95.

Commitment

To assess commitment to relationship we used the 15-item commitment measure,22 which estimates the level to which a partner or spouse is committed to the relationship. It comprises three subscales equivalent to the theoretical proposition of the investment model,11 presented earlier. Participants were asked to rate each item on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). Total score ranged from 15 to 90, with higher scores indicating stronger commitment to the relationship. In the present study, the Cronbach α = 0.91.

Caregiving Burden

Caregiving burden was assessed using the Zarit Burden Interview,23 a 22-item self-report inventory that measures, originally, the subjective burden of familial caregivers of individuals with dementia. Answers are given on a 5-point Likert scale, with responses from 0 (never) to 4 (nearly always) and a possible total score of 88. The 22 items evaluate caregiver issues of concern, such as health, social and personal life, financial situation, emotional well-being, and interpersonal relationships. In the present study we used the Greek version of the scale.24 Reliability analysis yielded very satisfactory results (Cronbach α = 0.91).

Prorelational Behavioral Tendencies

To assess prorelational behavioral tendencies we used an adapted version of the Prosocial Tendencies Measure developed by Carlo and Randall.17 The original tool consists of a 23-item self-report measure developed to estimate college students’ tendencies toward prosocial behavior. It is composed of six subscales: public, emotional, compliant, altruism, anonymous, and dire. In the present study, we used items regarding the first four subscales. Thus, the scale consisted of 15 items. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which items described themselves on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 6 (describes me greatly). For the 15-item version of the scale used in the present study, Cronbach α = 0.81.

Statistical Analyses

We combined basic descriptive statistics and a structural equation model (SEM) using IBM SPSS Amos, version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). In general, SEMs allow for analysis of the relationships between observed and unobserved or latent factors by combining key elements of regression, path, and factor analysis methods. The SEM in this study included eight exogenous (or independent) variables to account for possible confounding direct and indirect relationship effects of respondents’ personal characteristics and three additional key factors, namely, caregiving burden, commitment to relationship, and prorelational behavioral tendencies, on the final and mediating endogenous (dependent) variable, which represents relational satisfaction. Respondents’ characteristics included age, sex, and type and duration of relationship. In addition, caregiving burden, commitment to relationship, and prorelational behavioral tendencies represented key factors. In particular, the last two key factors are latent constructs, and they were developed via confirmatory factor analysis using three and four individual indicator variables, respectively.

To evaluate the overall model fit we used the traditional measure for evaluation provided by the well-known Pearson χ2 test. The alternative goodness-of-fit indices, based on the χ2 statistic, have been used, including the normed χ2/df statistic, the comparative fit index, the Tucker-Lewis Index, and the root mean square error of approximation. Furthermore, the applicability of the proposed SEM to the data estimating the parameters of the model (factor loadings or regression parameters) was checked through the maximum likelihood method. Maximum likelihood estimators have desirable asymptotic properties and assume multivariate normality of the observed variables. However, it has been found that they are robust in violating the normality assumption. Initially, the significance of the model parameters was tested (partial evaluation fit in SEM) for their reliability and validity.

Results

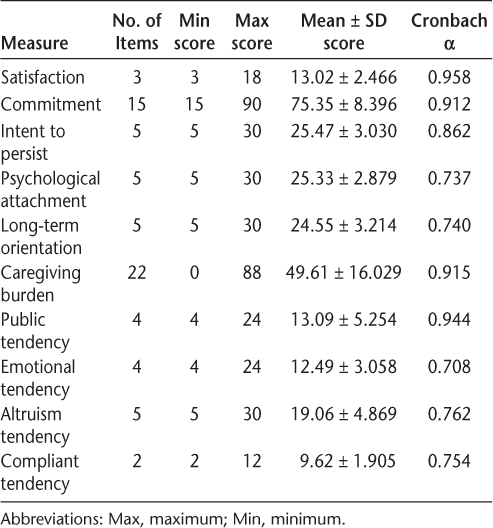

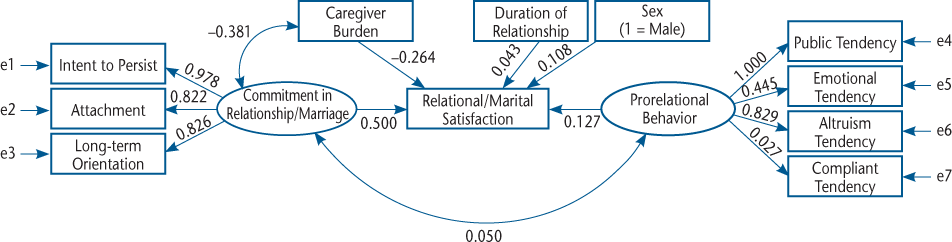

We received 995 initial requests for participation in the study. Participants were given 10 days to complete the questionnaire. We collected 909 questionnaires (633 paper/pencil and 276 online). The sample of 909 participants was composed mostly of men (62.5%), whose mean ± SD age was 48.9 ± 27.13 (range, 25–80) years. Most participants (85.0%) were married, and the mean ± SD duration of marriage/relationship was 13.39 ± 9.34 (range, 1–60) years. Relational satisfaction was high (mean ± SD satisfaction score, 13.02 ± 2.47 [range, 3–18]), and the caregiving burden was moderate (49.61 ± 16.07 [range, 4–90]). Regarding the two latent factors, it seemed that commitment to relationship was mostly defined by intent to persist and less by long-term orientation and psychological attachment (factor loadings of 0.978, 0.826, and 0.822, respectively). Prorelational behavioral tendencies were mainly defined by the public and altruism types and less by the emotional and compliant types (factor loadings of 1.000, 0.829, 0.445, and 0.027, respectively). For reasons of brevity, the full description of these indicator variables, along with the corresponding latent variables they measure, and factor analysis results (standardized factor loadings and fit statistics) are presented in Table 1. The two latent factors—commitment to relationship and prorelational tendencies—reached a good fit to the data (Table 1), with construct validity within the acceptable range (≥0.980). Also, most of the considered indicator variables were significant (P < .001). Besides factor analysis, Table 1 provides sample statistics and descriptions of the variables used in the analysis, together with their values and descriptive statistics.

Descriptive statistics and reliability evaluation of psychometric measures

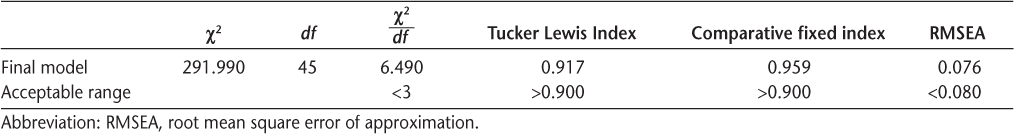

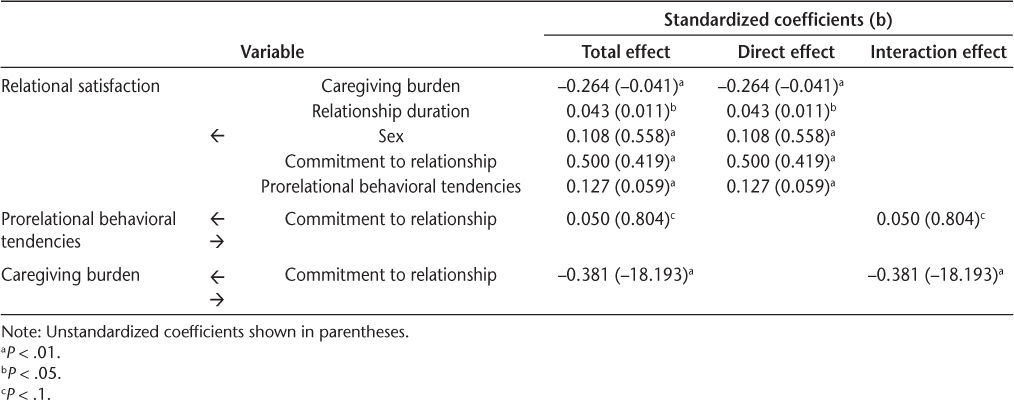

Results concerning goodness-of-fit indicators of the SEM model are given in Table S1 (published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org) suggesting adequate fit of the final model to the data. Fit measures for the final model are shown in Table 2. Direct, indirect, and total standardized effects for the final SEM are given in Table 3.

Fit measures for final structural equation model

Direct, indirect, and total standardized effects for final structural equation model

Reliability was tested by means of R2 criterion and validity via the t test. Two of the SEM parameters, namely, relationship type (P = .146) and age (P = .517), were found to be nonsignificant and were removed from the analysis. Then, the analysis was repeated among the rest of the variables. The final SEM including only the statistically significant variables, at either 0.10 or 0.001 levels, is presented in Figure 1 as means of standardized path coefficients and in Table 2 as standardized and unstandardized coefficients.

Final structural equation model for relational satisfaction of spousal/partner informal caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis and factors related (direct, standardized effects and interactions)

Commitment to relationship had the highest positive effect on relational satisfaction (b = 0.500, P < .001), implying that the higher the commitment to the relationship, the higher the satisfaction. Furthermore, commitment to relationship was found to interact positively with prorelational behavioral tendencies, pinpointing the second highest direct positive effect on relational satisfaction (b = 0.1277, P < .001). This finding indicates that relational satisfaction is mediated by both commitment to relationship and prorelational behavioral tendencies. Nevertheless, note that the interaction effect of the latent variables on relational satisfaction is weak (b = 0.050, P < .10). Still, the positive relationship obtained permits the following comment: informal caregivers who are committed to their relationship tend to illustrate a higher level of prorelational behavioral tendencies, which leads to higher satisfaction in their relationship. On the other hand, informal caregivers who scored high on the prorelational behavioral tendencies scale seemed to be more committed to their relationship and consequently more satisfied with their relationship. Caregiving burden had a direct negative effect on relational satisfaction (b = −0.264, P < .001). Also, the SEM yielded a negative interaction between caregiving burden and commitment to relationship (b = −0.381, P < .001).

Results concerning the effect of the demographic characteristics revealed a direct effect between sex and level of relational satisfaction (b = 0.108, P < .001). The positive value of the coefficient means that male informal caregivers tended to be more satisfied with their relationship than female informal caregivers. Finally, duration of relationship seemed to have the lowest positive direct effect on relational satisfaction (b = 0.043, P < .10), meaning that spousal/partner informal caregivers in longer relationships tended to be more satisfied from their relationship with their spouse/partner who has MS.

Discussion

Participants were found to have a high level of relational satisfaction. Also, commitment to relationship was found to be high, and, according to the cutoff criteria of the Zarit Burden Interview, caregiving burden was moderate.25 Taken together, these findings initially are surprising because previous research not only yielded lower levels of relational satisfaction of spousal/partner informal caregivers of patients with MS10 but also found that when spousal/partner informal caregivers report considerable levels of caregiving burden they also report moderate-to-low levels of relational satisfaction.18 Moreover, although caregiving burden was found to be moderate, commitment to relationship was high. Results obtained by the SEM might be able to clarify things. That is, commitment to relationship was found to have the highest positive effect on relational satisfaction. According to the investment model11 and the relative data,12 this finding is not surprising. Still, this study assessed the three components of commitment to relationship and examined the degree to which each one of them contributes to the formation of commitment. The SEM highlighted intent to persist as the highest contributing factor. This particular finding is in line with Rusbult’s theoretical standpoint11 about the transformation of personal to dyadic interest, through the dependence that one spouse/partner develops toward the other. In their meta-analysis regarding the determinants of commitment in the context of the investment model, Le and Agnew13 denote that intent to persist is an important determinant of commitment to relationship and of the satisfaction stemming from it because the spouse/partner seems to view the relationship as a personal bet that he or she wishes to win. Furthermore, in the case of a spouse/partner who at the same time is the informal caregiver of a person with a chronic disease, intent to persist could be a force that motivates the spousal/partner informal caregiver to continue pursuing satisfaction and quality from a relationship that is negatively affected by the health condition of the other spouse/partner.

The SEM also yielded a direct negative effect of caregiving burden on relational satisfaction. This finding is similar to findings obtained by relative studies.7 Still, in the present study, relational satisfaction was found to be moderate to high, although participants reported moderate levels of burden. A plausible answer to this seeming paradox might come from examination of the indirect effect of caregiving burden on relational satisfaction through commitment to relationship. Specifically, it was found that caregiving burden affects and is affected by commitment to relationship. That is, not only that the higher the sense of burden the lower the commitment is, but also the higher the commitment the lower the sense of burden would be. This finding could support the speculation that commitment to relationship or having intent to persist as the most determining component could hinder the negative effect of caregiving burden on relational satisfaction. As far as prorelational behavioral tendencies are concerned, the SEM highlighted the public and altruism types as those with the highest positive effect on relational satisfaction. The finding regarding the altruism type seems to offer empirical support to the investment model of commitment processes,14 which supports the notion that long-term partners tend to behave in manners that benefit their partner and their relationship even with personal cost for them. What is more interesting is the high impact of the public type on relational satisfaction because this type refers to performance of prorelational behavior in the presence of others for them to form a positive view about the caregiver. Moreover, taking into account the observed positive, yet weak, relationship between the latent variables of commitment to relationship and prorelational behavioral tendencies, the following claim could cautiously be made: Undoubtedly, spousal/partner informal caregivers of individuals with MS carry a burden that is able to negatively affect their relational satisfaction; however, their commitment to relationship, namely, their intent to persist, would form a factor hindering the negative consequences of caregiving burden on relational satisfaction. Thus, the tendency toward recognition of their caregiving efforts by others seems preferable not only in counterbalancing the negative effects of burden but also in strengthening the satisfaction from a relationship with a spouse/partner who has a chronic disease and the illness has been found6 to negatively affect the family and especially the member who becomes the informal caregiver.

This study has some limitations. Although the number of people who participated in the study is large, the sampling method can be characterized as convenient, a fact that limits the generalization of the findings. Also, the lack of a control group that would enable comparisons with the general population limits the generalization of the findings as well. Next, the number of nonspousal informal caregivers who participated in the study is very small compared with the number of spousal participants. This might be why no significant differences were found with respect to participants’ relationship status (partner or spouse).

In conclusion, it could be argued that the present study accomplished its goals. Building on the Rusbult investment model, the study directly assessed the relational satisfaction of spousal/partner informal caregivers of people with MS in a large sample. Moreover, interesting findings regarding the components of commitment to relationship and their role in counterbalancing the negative effects of caregiving burden on relational satisfaction were brought to light. Furthermore, the present findings highlight the need for further research on relational satisfaction of spousal/partner informal caregivers of people with MS by focusing on the motives that underlie their prorelational behavior toward their spouses/partners and on the content of commitment to relationship.

PRACTICE POINTS

Spousal/partner informal caregivers of individuals with MS reported moderate-to-high levels of caregiving burden, commitment, and relational satisfaction.

Commitment to relationship is positively associated with relational satisfaction.

Caregiving burden affects relational satisfaction directly and negatively. Still, the higher the burden the lower the commitment, and the higher the commitment the lower the burden. This two-way relationship indirectly affects relational satisfaction.

Prorelational behavioral tendencies are positively associated with relational satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

Ms Tzitzika is a PhD student, Department of Psychology, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Greece.

References

Murray TJ. Multiple Sclerosis: The History of a Disease. Demos Publishing; 2005.

McCabe MP, McKern S, McDonald E, Vowels LM. Changes over time in sexual and relationship functioning of people with multiple sclerosis. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29:305–321.

Thomas P, Thomas S, Hillier C, Galvin K, Baker R, Cole J. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Library website. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004431.pub2/full?highlightAbstract=sclerosis|psychological|interv entions|multipl|four|psycholog|for|multiple|withdrawn|sclerosi|intervent. Published January 25, 2006. Accessed December 11, 2018.

LaRocca NG, Kalb RC, Foley FW, Caruso LS. Assessment of psychosocial outcomes. J Neurol Rehabil. 1993;7:109–116.

Mohr DC, Dick LP, Russo D, et al. The psychosocial impact of multiple sclerosis: exploring the patient’s perspective. Health Psychol. 1998;18:376–382.

Boland P, Levack WM, Hudson S, Bell EA. A qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators to coping experienced by couples when one has multiple sclerosis. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2018;25:240–246.

Corry M, While A. The needs of carers of people with multiple sclerosis: a literature review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23:569–588.

Valvano AK, Rollock MJ, Hudson WH, Goodworth MC, Lopez E, Stepleman L. Sexual communication, sexual satisfaction, and relationship quality in people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2018;63:267–275.

Ghafari S, Khoshknab MF, Norouzi K, Mohamadi E. Spousal support as experienced by people with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. J Neurol Nurs. 2014;46:15–24.

Opara J, Brola W. Quality of life and burden in caregivers of multiple sclerosis patients. Physiother Health Activity. 2018;25:9–16.

Rusbult CE. A longitudinal test of the investment model: the development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involvements. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;45:101–117.

Le BI, Dove NL, Agnew CR, Korn MS, Mutso AA. Predicting non-marital romantic relationship dissolution: a meta-analytic synthesis. Pers Relationships. 2010;17:377–390.

Le B, Agnew CR. Commitment and its theorized determinants: a meta-analysis of the investment model. Pers Relationships. 2003;10:37–57.

Rusbult CE, Agnew CR, Arriaga XB. The investment model of commitment processes. In: Van Lange PA, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, ed. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. Sage Publications Ltd; 2012:218–231.

Collins NL, Guichard AC, Ford MB, Feeney BC. Responding to need in intimate relationships: normative processes and individual differences. In: Mikulincer M, Goodman GS, ed. Dynamics of Romantic Love: Attachment, Caregiving, and Sex. Guilford Press; 2006:149–189.

Neff LA, Karney BR. Gender differences in social support: a question of skill or responsiveness? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:79–90.

Carlo G, Randall BA. Development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. J Youth Adolescence. 2002;31:31–34.

Akkuş Y. Multiple sclerosis patient caregivers: the relationship between their psychological and social needs and burden levels. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:326–333.

Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Huang C. Caregiver burden among informal caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2011;33:76–83.

Özmen S, Yurttaş A. Determination of care burden of caregivers of patients with multiple sclerosis in Turkey. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bn/2018/7205046/abs/. Published 2018. Accessed October 11, 2018.

Schumm WR, Paff-Bergen LA, Hatch RC, et al. Concurrent and discriminant validity of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale. J Marriage Fam. 1986;48:381–387.

Rusbult CE, Kumashiro M, Kubacka KE, Finkel J. “The part of me that you bring out”: ideal similarity and the Michelangelo phenomenon. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96:61–82.

Zarit SH, Orr NK, Zarit JM. The Hidden Victims of Alzheimer’s Disease: Families Under Stress. New York University Press; 1985.

Papastavrou E, Kalokerinou A, Papacostas SS, Tsangari H, Sourtzi P. Caring for a relative with dementia: family caregiver burden. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:446–457.

Schreiner AS, Morimoto T, Arai Y, Zarit S. Assessing family caregiver’s mental health using a statistically derived cut-off score for the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10:107–111.