Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Perceptions of Multiple Sclerosis in Hispanic Americans

Author(s):

Background:

Illness perceptions have been reported to be important determinants of multiple sclerosis (MS)–related well-being. Hispanic culture is defined by strong cultural beliefs in which illness is often perceived to arise from strong emotions. Understanding the perceptions of MS in Hispanic Americans may provide a better understanding of cultural barriers that may exist. The purpose of this study was to describe Hispanic American perceptions of MS.

Methods:

We gathered information from semistructured interviews, focus groups, and participant responses from the University of Southern California Hispanic MS Registry. This information was then stratified into a matrix of environmental, biological, and sociocultural determinants. Differences were examined by place of birth, treatment preference, and ambulatory difficulty. Logistic regression was used to investigate the relationship between sociocultural perceptions, place of birth, and ambulation.

Results:

Most participants were female (n = 64, 61%), US born (n = 64, 61%), and receiving treatment for MS. Participants cited environmental and sociocultural perceptions, with significant differences noted by place of birth. Sociocultural factors such as strong emotions were almost four times more commonly perceived in immigrants compared with US-born participants (adjusted odds ratio, 3.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.12–11.90; P = .03). Male, low-education, and low-income participants were also more likely to perceive MS to be a result of strong emotions, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusions:

Hispanic American perceptions of MS differ by place of birth, with reports of cultural idioms more common among immigrants, which could affect disease management. These findings may be useful in designing educational interventions to improve MS-related well-being in Hispanic populations.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a complex inflammatory, demyelinating, and progressive disorder of the central nervous system that negatively affects quality of life and disproportionately affects women. The number of Hispanic individuals with MS in the United States is expected to increase, given estimates that the proportion of Hispanics in the US population will rise from 14% in 2005 to 29% by 2050.1 Despite increases in MS diagnoses in the Hispanic population and increases in the availability of MS educational material to the population in general, observations suggest that Hispanics with MS lack awareness of MS and its treatments.2–4 We previously reported that Hispanics with MS who immigrated at a later age to the United States are twice as likely to have ambulatory disability compared with US-born Hispanics with MS.5 Illness perceptions have been reported to be important determinants of MS-related well-being, and place of birth could play an important role in illness perceptions in Hispanic patients with MS. These previous findings may reflect differences in social, environmental, and cultural factors that may act as barriers to accessibility and utilization of health-care services. Failure to recognize illness perceptions in this population could significantly affect short- and long-term MS disease management.

An individual's perception of illness is a complex, multidimensional process comprising cognitive representations or beliefs that patients have about their illness.6 Research supports illness perceptions to be important determinants of behavior, and they have been associated with a variety of important outcomes, such as treatment adherence and functional recovery.7–9 Studies of chronic conditions such as diabetes and stroke in Hispanic populations have shown that perceptions of illness differ by ethnicity and are important factors affecting self-care in Hispanics.10–13 A recent study found that stroke awareness significantly differed between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites, and perceived barriers were part of this difference.14 That study also suggests that Hispanic patients report less control over their health because of perceptions, which, in turn, limit their participation in interventions. In addition, acculturation and health literacy have been reported to play an important role in illness perceptions among Hispanics.15 Recently, illness perceptions have been described in white populations to be important determinants of MS treatment preference and management.16–20 However, perceptions of the cause of MS have not been particularly studied in Hispanic Americans with MS. Understanding perceptions of illness in Hispanics with MS could nurture the development of culturally competent programs, identify gaps in health-care efficacy, and provide an avenue for future health interventions to reduce ethnic and racial disparities in MS.

Hispanic culture is characterized by strong values attached to family and cultural beliefs.21 Susto (fright), ataque de nervios (attack of nerves), and tristeza (sadness) are cultural beliefs in which disease is thought to arise from strong emotions.12,22 These illness perceptions can have a strong influence on outcomes, coping strategies, behaviors in chronic illnesses, and self-management such as adherence and preferences for treatment.23–25 The theoretical framework of the present investigation is rooted in two observations. First, health literacy affects adults in all racial and ethnic groups, with a greater proportion of Hispanics (65%) than non-Hispanic whites (28%) with basic or below basic health literacy.26 Second, perceptions of disease can be modified by improving our understanding of existing perceptions, which can then be used to modify health literacy. The present study explores the beliefs about MS arising from MS focus groups in Los Angeles, California, intended to promote MS health literacy in underserved Hispanics.

Methods

Study Population

We recruited participants who self-identified as Hispanics with MS who entered the Hispanic MS Registry at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles County between December 1, 2014, and August 31, 2015. Hispanic was defined using the National Institutes of Health criteria for minority inclusion in research as a person who self-identifies as Hispanic or Latino of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race.27 The Hispanic MS Registry is a collection of prevalent and incident cases of MS that recruits in-person from two MS specialty clinics at USC; it is fully described elsewhere.28

All the study participants were recruited at the time of enrollment into the Hispanic MS Registry (N = 105). After collection of basic demographic and clinical information, each participant was asked the same open-ended question: “Are there any significant events you would like to report that led to your MS onset?” Immediately after enrollment, most of the study participants (n = 75) completed a one-on-one, semistructured interview to further elaborate on their perceptions of MS. The remaining participants (n = 30) agreed to attend one of three focus group sessions, particularly useful in enabling individuals to clarify and voice their opinions.

None of the participants were exclusively Spanish speaking, and no participants were excluded. In fact, all of the participants provided consent in English despite the fact that some preferred speaking Spanish during the focus group sessions. Patients who provide consent in Spanish are usually considered to be at risk for a potential language barrier, and in the USC Hispanic MS Registry, that rate is currently 17%. Because all consent was obtained in English, the potential of encountering language barriers in the present study participants was considered to be minimal. This study was approved by the USC institutional review board, and all the patients gave informed consent before participation.

Data Collection

Data collection took place between December 1, 2014, and August 31, 2015, during registry enrollment, one-on-one semistructured interviews, and focus group sessions. A trained interviewer and coordinator of the USC Hispanic MS Registry (AP) conducted all the semistructured interviews. The local chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society organized three 90-minute focus group sessions at the Los Angeles County medical facility's Wellness Center. The same bilingual (Spanish/English) trained staff facilitated each focus group meeting: the National Multiple Sclerosis Society Wellness Center director (Mercy Willard, MPH), the coordinator of the USC Hispanic MS Registry (AP), an MS neurologist (LA), and an MS nurse practitioner (LT). Before each discussion, the facilitators explained to the participants that information gathered from the semistructured interviews and focus groups would be used for research purposes.

To gain insight into participant perceptions of the cause of MS, analysis of the information was made following the principles of qualitative research.29 Information collected from each participant included year of diagnosis, first symptom, type of MS, perception of walking (fully ambulatory or not), educational level, type of clinic visited (public vs. private), and type of MS treatment delivery (oral vs. injection vs. infusion). Clinical variables such as diagnosis of MS and medication use were confirmed via medical record review. When asking the open-ended question involving perceptions of MS causation, the interviewer read the question exactly as it appeared in the enrollment questionnaire to minimize ascertainment bias. From participant responses, including in-depth information gathered from the one-on-one interviews and focus group sessions, a matrix of the main topics was created for the collected perceptions of MS (ie, biological, environmental, and sociocultural) (Figure 1). Using the matrix, we independently identified and coded key words and common themes that appeared throughout the interviews and responses. To maintain the richness of the information obtained during the interviews, the bilingual research staff translated and presented direct quotes in the results section. Although all participants may not have repeated the specific words, the meaning was expressed and widely affirmed between researchers. In cases in which a Spanish word had no suitable English translation, we used the Spanish word and described its meaning in the text (eg, susto).

Matrix of reported perceptions about the cause of multiple sclerosis (MS) among Hispanic study participants

Each response was captured as is by hand, electronically entered into the Common Application Framework Extensible electronic framework, and later independently coded using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). After a literature review of other chronic illnesses, data collected from the focus groups and in-depth interviews were used to develop a conceptual framework. This led to the stratification of responses into “yes” or “no” under environmental, sociocultural, and biological categories. To confirm the credibility of the results and avoid selective perceptions, unclear answers were discussed during the focus group sessions and in the research group when possible.

Statistical Analysis

A descriptive cross-sectional design was used for this research. All the analyses were conducted in Hispanic patients with MS with complete answers on the questionnaire, age at immigration, and birthplace information. Ambulatory difficulty was self-reported. Statistically significant differences stratified by place of birth were identified using χ2 tests for binary or categorical variables (ie, MS type and sex) and t tests for continuous variables (ie, age at onset, age at diagnosis, and disease duration). We used multivariate logistic regression to evaluate the association between place of birth (US born or immigrant), age at immigration (restricted to immigrants), and sociocultural perceptions that had an emotional origin (ie, susto and tristeza). We adjusted for sex, educational level, and income (<$40,000 or >$40,000 annually). All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), and an a priori α level of .05 was used to declare statistical significance.

Results

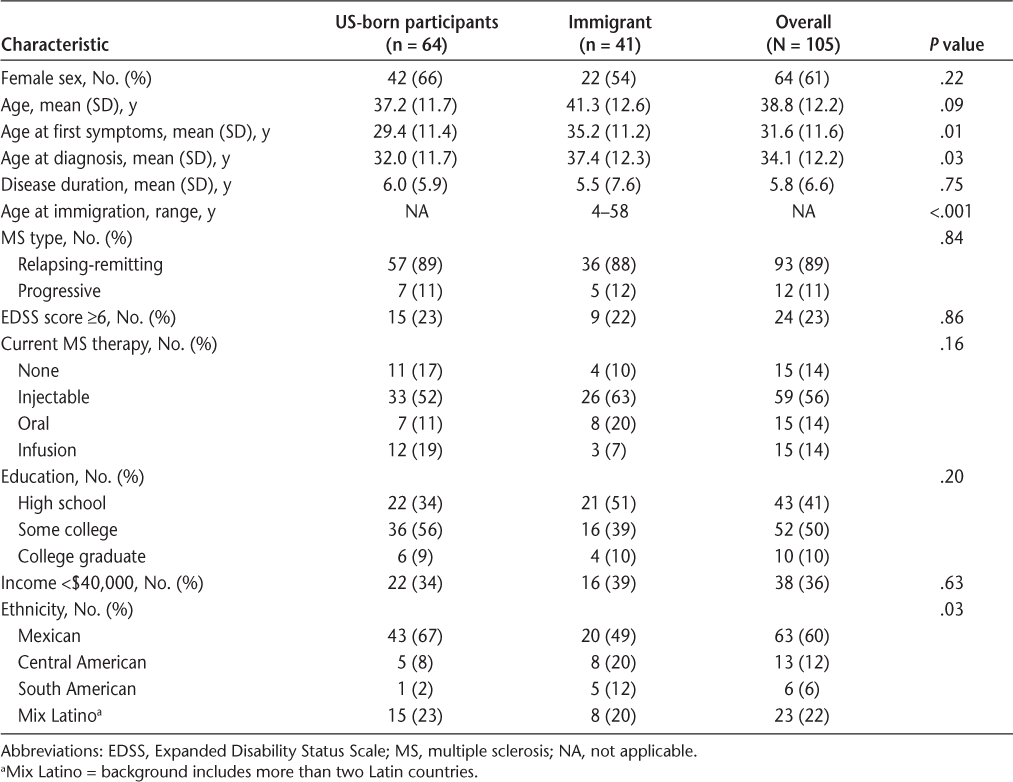

Of the 105 responders, most were female (61%), were born in the United States (61%), had relapsing forms of MS (89%) with a mean (SD) disease duration of 5.8 (6.6) years, and had some college education or more (59%) (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of 105 Hispanics with MS

Stratified by place of birth, US-born participants were significantly younger at the onset of the first MS symptoms and diagnosis. A greater proportion of the US-born group identified with a Mexican background, and a greater proportion of the immigrant group identified with a Central American background. There were no significant differences by income, level of education, disability status, or type of treatment delivery.

Beliefs About Perceived Causes of MS

After the independent analysis of each answer provided, a matrix was created where answers were matched by three themes: environmental, sociocultural, and biological (Figure 1). There were no differences in the reported perceived causes of MS when stratified by sex.

Environmental

In general, most participants identified environmental factors as the perceived cause of MS (86%), such as “too much stress” and “poor diet.” One participant stated, “I was working two jobs and I was too stressed out, no time to relax.” Another participant emphasized the effect of “family stress and too much drama at home . . . we Hispanics overreact.” Many participants cited food habits such as “eating fast food,” “not having time to cook,” “the food in the US,” and “being overweight.” Although mentioned less frequently, a few participants expressed that “working under hot weather” and “steam” likely precipitated their MS. In the end, poor diet and overworking were identified as the most commonly perceived causes of increased susceptibility to MS. Other identified causes included history of infectious mononucleosis and vitamin D deficiency.

Sociocultural

In addition to the environmental factors, many participants expressed sociocultural factors such as supernatural events and experiencing strong emotions (57%) that preceded the onset of their MS. The most commonly cited emotional state was susto (16%), which is interpreted as fright or surprise in the English language. One participant stated, “I think it was because I almost drowned as a child . . . since then I have felt poorly and I think this is due to un gran susto” (immigrant). Another participant discounted the possibility that MS could have a genetic component with the following statement: “My doctor told me that MS could be a result of genes. There is no one in my family with MS. . . . I checked. I really think I got MS because my mother dropped me as a child” (US born).

In the example presented later herein, a participant contrasts the cause of MS identified by her doctor with her own belief about the cause of MS (sadness, or tristeza): “When we lost our son we were also having domestic problems. I am certain I was very sad, then I developed MS” (immigrant). In this additional example, the participant discounts a biological cause and instead cites a gift from God: “I was in church when I lost my eyesight, I know God gives different gifts to each. . . . I trust in God.”

Biological

Few participants reported biological or hereditary reasons for MS causation (18%).

Matrix of Disease Perceptions by Place of Birth

When examining perceptions by place of birth (Figure 2), there were no significant differences between US-born and immigrant participants by perceived environmental encounters (93% vs. 81%, P = .10). However, stress was more commonly cited as a cause of MS in the US-born participants (91% vs. 68%, P = .03). Sociocultural factors were more frequently reported in the immigrant group (P = .02), with the perception of susto being the most commonly perceived cause of MS in immigrants versus US-born participants (27% vs. 7%, P = .05). Tristeza was the second most common perceived cause of MS; however, tristeza was not found to be significantly different between immigrant and US-born participants (12% vs. 10%, P = .89). Perceptions of biological causes were not found to be different by place of birth (P = .20).

Perceived causes of multiple sclerosis (MS) in Hispanics by place of birth

Treatment Preference and Reported Ambulation by Perception Category

There were no significant differences between perception categories and treatment preference (Table 2). However, a greater proportion of patients who reported biological perceptions were receiving oral or infusion therapy. Interestingly, not receiving treatment was more commonly reported by those who reported perceptions associated with sociocultural factors. In addition, individuals who reported difficulty ambulating were more likely to be receiving treatment.

Perceived cause of MS, ambulation status, and current MS treatment

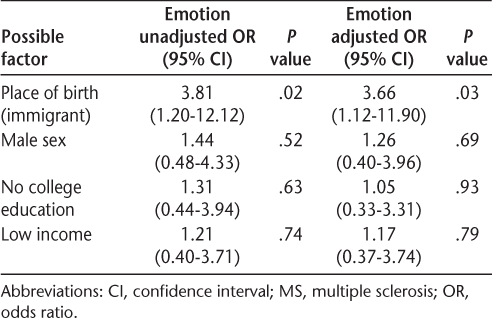

The Risk of Strong Emotions in Hispanic Immigrants

Because we saw significant differences by place of birth when examining the belief that MS is caused by strong emotions, we investigated the risk of these perceptions by place of birth (immigrant vs. US born) using multivariable logistic regression. After adjusting for sex, education, and income, being an immigrant significantly increased the risk of believing an emotional perception to be the cause of MS (odds ratio, 3.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.12–11.90; P = .03). Male, low-education, and low-income participants were also more likely to perceive MS as a strong emotion, but these were not statistically significant (Table 3).

Logistic regression analysis of the association of MS belief as a result of emotion (susto and tristeza) and place of birth in 105 Hispanics with MS

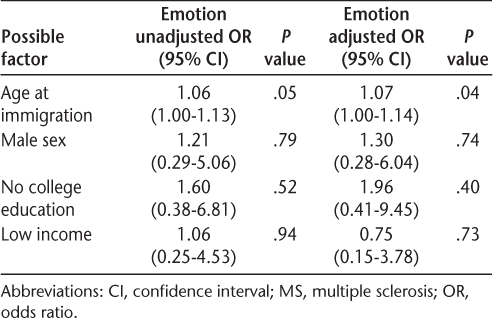

In a restricted model, we further investigated the perception of strong emotions as the cause of MS in the immigrant population using age at immigration. In this multivariable logistic model, older age at immigration is significantly associated with the risk of perceiving MS to be the result of strong emotions (Table 4).

Logistic regression analysis of the association of MS belief as a result of emotion (susto and tristeza) and age at immigration in 41 immigrant Hispanics with MS only

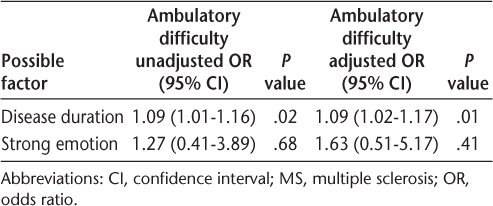

We then investigated whether perceiving MS as a result of strong emotions would increase the risk of ambulatory difficulty as reported by the patient. In this model, the risk of ambulatory problems is significantly greater for those with longer disease duration but not for those who report strong emotions (adjusted odds ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 0.51–5.17) (Table 5).

Logistic regression analysis of the association of ambulatory difficulty and MS belief as a result of emotion in 105 Hispanics with MS

Discussion

We used data from focus groups and related questionnaires of Hispanic adults with MS residing in Southern California, specifically in Los Angeles County, to examine beliefs about the cause of MS. The findings from this study suggest that perceptions of the cause of MS differ among Hispanics, and place of birth and age at immigration may influence these perceptions. In addition, data from this sample suggest that participants draw on two main belief systems to describe the causes of MS: stress and sociocultural factors that derive from strong emotions. Culturally related emotions such as susto and tristeza were found to be the most commonly perceived causes of MS in Hispanics, even among the educated and those living in the United States since birth. This is not surprising as susto and tristeza are common cultural idioms of distress reportedly used by Hispanics to explain clinical presentations in other diseases that affect them, such as type 2 diabetes and stroke.7,10,21 In addition, place of birth and age at immigration in the immigrant population were found to be significant factors in the risk of perceiving MS to be the result of strong emotions.

The present findings about the causes of MS are consistent with the health literature on other chronic medical conditions prevalent in Hispanic populations.25 Although the present study did not focus on comparison with non-Hispanics, a recent stroke study found that significant differences exist by race/ethnicity and that perceptions of illness are significant factors affecting self-care, particularly in Hispanics.14 Negative and unrealistic perceptions of illness have been shown to affect symptoms and self-management of disease, which could hinder clinical interventions and outcomes in this population.30 The emphasis of stress as a cause of MS and the value attributed to healthy eating and stress reduction suggests that Hispanics also believe in espiritism, whereby health is defined synergistically as a continuation of mind, body, and spirit.31,32 Valuing leisure, a healthy diet (eg, concern with fast food), and stress reduction were common comments made by many study participants, suggesting that some cultural beliefs could actually help with disease management when emphasized.

Previous investigations of Hispanic explanatory models of chronic conditions such as diabetes suggest that it is common for Hispanics to believe that strong emotions make the body susceptible to illness.9,12 Studies have shown that when asked more specifically, most individuals can point to a specific episode of susto, or a profound emotional experience, that precipitated the disease. These perceptions have the potential to translate into negative patient illness perceptions, which have been reported to increase the likelihood of future disability and symptoms in chronic medical conditions such as asthma.33 Such beliefs warrant the development of a more comprehensive explanatory model of disease and require that treatments be tailored to overcome these barriers and increase awareness.9

Although limited data exist in MS, recent research suggests that MS-related well-being is primarily predicted by patients' own illness beliefs. Bassi and colleagues17 also showed that beyond the beliefs of the individuals affected with MS, the caregivers' well-being was primarily predicted by their own beliefs as well. General self-efficacy, perception of treatment control, and realistic MS timeline perspectives have been reported to be important correlates of self-management in MS, more so than clinical variables.19 Although the present sample varied regarding level of education, each participant had a minimum of a high school education. Interestingly, reports of obtaining some college education were higher than expected, suggesting that although most participants with MS were educated, they have culturally rooted perceptions that could be factors in determining well-being.

The findings that place of birth and age at immigration influence the perception of MS as a result of strong emotion indicate that MS outcomes in Hispanics could be affected by cultural factors. Those most likely to experience susto could be less acculturated. We previously demonstrated how place of birth and age at immigration relate to disease severity in Hispanics with MS, where older immigrants incur twice the risk of ambulatory disability compared with US-born Hispanics.5 However, birthplace is unlikely to be an accurate estimate of sociocultural integration, and future studies aimed at health promotion in MS will need to integrate better measures that account for individual integration into society (ie, acculturation scales).

These findings have some relevance for public health and clinical practice. Because of the growing scientific interest in identifying effective health interventions to reduce ethnic and racial health disparities, these findings may have significant implications for the clinical care and self-management of MS in Hispanics. The present findings support the need to promote awareness among Hispanics with MS about the biological basis for MS. Targeted messaging that uses media outlets popular in this population, such as a short film or “mini-telenovela,” could be especially effective in addressing the perceptions and possibly the general lack of MS awareness among Hispanics. Similarly, increasing physician understanding of sociocultural factors that may be present in a patient's explanatory model of disease may help develop approaches to MS care that more holistically treat Hispanic patients with MS.

There are limitations to this cross-sectional study. Because qualitative studies in MS are few and none have involved Hispanic Americans with MS, potential limitations regarding adequate sample size must be acknowledged. Nevertheless, we performed a review of the literature and followed conduct procedures used in qualitative research to guide the determination of sample size. Along with being well sized for promoting interaction from participants and conducive to obtaining meaningful feedback, the sample size was considered large enough to ensure that most (if not all) of the participants' perceptions were explored. Data collection was conducted on a convenience sample of participants likely to attend focus group sessions and who were of mostly Mexican and Central American background, limiting its generalizability. We recognize that there are considerable differences in health beliefs and practices across subgroups of Hispanics, and we were not able to explore such differences in this study. Nevertheless, this study is highly representative of Southern Californian diversity and illustrates a potentially important avenue for the study and application of sociocultural factors in the examination of MS in Hispanic American populations. Although studies about cultural beliefs provide insight into the everyday experiences of people with MS, more research is needed to examine how such experiences may contribute to the self-management and mediation of MS disease severity and progression. In addition, this study should not be used to generalize cultural beliefs or illness perceptions of MS in all Hispanics but rather for sensitization about potentially relevant issues for Hispanics with MS.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that Hispanics with MS in Southern California strongly differ in what they perceive to be the cause of MS, and perceptions are further influenced by place of birth and age at immigration. Future studies and interventions should focus on identifying and addressing misconceptions as well as increasing awareness of MS in Hispanics and their providers through tailored health education interventions with the goal of improving the provision of patient-centered care. The use of culturally tailored messaging with relevant characters and contextual narratives that reflect the concerns and diverse beliefs of Hispanic Americans could be an effective means of transmitting important MS information with hopes of preventing disability.

PracticePoints

Hispanic culture is defined by strong cultural beliefs in which illness may be perceived to arise from strong emotions.

Members of the Hispanic MS Registry at the University of Southern California who participated in semistructured interviews and focus group sessions were found to have strong sociocultural perceptions of MS, and MS causation beliefs differed by place of birth and age at immigration.

To improve MS-related well-being in Hispanic populations, ideal interventions should increase MS awareness and address cultural idioms that have the potential to negatively affect MS care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jose Aparicio for his contribution to data collection; all the study participants; Marisela Robles, MPH, Cecilia Patino-Sutton, MD, PhD, and Katrina Kubicek, PhD, from the Southern California Community Leadership in Clinical and Translational Science Institute; and Mercy Willard, MPH, from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society for facilitating the focus groups.

References

Passel J, Cohn D. U.S. population projections: 2005–2050. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050. Published February 11, 2008. Accessed September 21, 2015.

Shabas D, Heffner M. Multiple sclerosis management for low-income minorities. Mult Scler. 2005; 11:635–640.

Khan O, Williams MJ, Amezcua L, Javed A, Larsen KE, Smrtka JM. Multiple sclerosis in US minority populations: clinical practice insights. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015; 5:132–142.

Buchanan RJ, Zuniga MA, Carrillo-Zuniga G, et al. A pilot study of Latinos with multiple sclerosis: demographic, disease, mental health, and psychosocial characteristics. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2011; 10:211–231.

Amezcua L, Conti DV, Liu L, Ledezma K, Langer-Gould AM. Place of birth, age of immigration, and disability in Hispanics with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015; 4:25–30.

Daleboudt GM, Broadbent E, Berger SP, Kaptein AA. Illness perceptions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and proliferative lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2011; 20:290–298.

Dura-Vila G, Hodes M. Cross-cultural study of idioms of distress among Spanish nationals and Hispanic American migrants: susto, nervios and ataque de nervios. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012; 47:1627–1637.

Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004; 119:239–243.

Kountz DS. Hypertension in ethnic populations: tailoring treatments. Clin Cornerstone. 2004; 6:39–48.

Boden-Albala B, Carman H, Moran M, Doyle M, Paik MC. Perception of recurrent stroke risk among black, white and Hispanic ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack survivors: the SWIFT study. Neuroepidemiology. 2011; 37:83–87.

Concha JB, Mayer SD, Mezuk BR, Avula D. Diabetes causation beliefs among Spanish-speaking patients. Diabetes Educ. 2016; 42:116–125.

Coronado GD, Thompson B, Tejeda S, Godina R. Attitudes and beliefs among Mexican Americans about type 2 diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004; 15:576–588.

Guarnaccia PJ, Lewis-Fernandez R, Marano MR. Toward a Puerto Rican popular nosology: nervios and ataque de nervios. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2003; 27:339–366.

Martinez M, Prabhakar N, Drake K, et al. Identification of barriers to stroke awareness and risk factor management unique to Hispanics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;13(1).

Rodriguez F, Hicks LS, Lopez L. Association of acculturation and country of origin with self-reported hypertension and diabetes in a heterogeneous Hispanic population. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:768.

de Seze J, Borgel F, Brudon F. Patient perceptions of multiple sclerosis and its treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012; 6:263–273.

Bassi M, Falautano M, Cilia S, et al. Illness perception and well-being among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2016; 23:33–52.

Buchanan RJ, Kaufman M, Zhu L, James W. Patient perceptions of multiple sclerosis-related care: comparisons by practice specialty of principal care physician. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008; 23:267–272.

Wilski M, Tasiemski T. Illness perception, treatment beliefs, self-esteem, and self-efficacy as correlates of self-management in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016; 133:338–345.

Lerdal A, Celius EG, Moum T. Perceptions of illness and its development in patients with multiple sclerosis: a prospective cohort study. J Adv Nurs. 2009; 65:184–192.

Hu J, Amirehsani K, Wallace DC, Letvak S. Perceptions of barriers in managing diabetes: perspectives of Hispanic immigrant patients and family members. Diabetes Educ. 2013; 39:494–503.

Razzouk D, Nogueira B, Mari Jde J. The contribution of Latin American and Caribbean countries on culture bound syndromes studies for the ICD-10 revision: key findings from a working in progress. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2011;33(suppl 1):S5–S20.

Ross S, Walker A, MacLeod MJ. Patient compliance in hypertension: role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Hum Hypertens. 2004; 18:607–613.

Petrie KJ, Jago LA, Devcich DA. The role of illness perceptions in patients with medical conditions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007; 20:163–167.

Poss J, Jezewski MA. The role and meaning of susto in Mexican Americans' explanatory model of type 2 diabetes. Med Anthropol Q. 2002; 16:360–377.

Llagas C, Snyder TD. Status and trends in the education of Hispanics. National Center for Education Statistics website. http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2003/2003008.pdf. Published April 15, 2003. Accessed September 21, 2015.

National Institutes of Health Office of Extramural Research. NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. National Institutes of Health website. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/guidelines_amended_10_2001.htm. Updated October 1, 2001. Accessed September 21, 2005.

Amezcua L, Lund BT, Weiner LP, Islam T. Multiple sclerosis in Hispanics: a study of clinical disease expression. Mult Scler. 2011; 17:1010–1016.

Barbour RS. The role of qualitative research in broadening the “evidence base” for clinical practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2000; 6:155–163.

Adames HY, Chavez-Duenas NY, Fuentes MA, et al. Integration of Latino/a cultural values into palliative health care: a culture centered model. Palliat Support Care. 2014; 12:149–157.

Cervantes JM. Mestizo spirituality: toward an integrated approach to psychotherapy for Latina/os. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2010; 47:527–539.

Guevara-Ramos LM. Espiritismo and medical care. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1216.

Petrie KJ, Perry K, Broadbent E, Weinman J. A text message programme designed to modify patients' illness and treatment beliefs improves self-reported adherence to asthma preventer medication. Br J Health Psychol. 2012; 17:74–84.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Amezcua has received honoraria for advisory boards and investigator-initiated grant support from Acorda, Biogen, Genzyme, and Novartis. Dr. Langer-Gould has received research funding from Biogen Idec, Hoffmann-La Roche, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant KL2TR000131 and Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute community engagement. The funding agencies had no role in the study design and conduct, data collection or analysis, or manuscript preparation.