Publication

Theme Article

International Journal of MS Care

Multiple Sclerosis Care in a Low/Middle-Income Setting in South West India

Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) awareness has increased in India, especially in the past decade. Growing awareness of the disease among medical specialists and the public and the availability of MRI in many cities in India are partly responsible. However, income inequity and the need for out-of-pocket spending create special challenges for MS care within the region. In low-income settings, some of these limitations may be partially mitigated through subsidized inpatient and outpatient care, prescription of generic and biosimilar alternatives of MS disease-modifying therapies, and remote monitoring of patients with stability. Improving the knowledge gap among medical professionals and generating country- specific guidelines are equally important. This paper will highlight some successful measures, using the example of the Mangalore Demyelinating Disease Registry.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) has been recognized in India since the early 1950s, as evidenced by early publications by Indian physicians who had trained in the United Kingdom and the United States.1,2 In the 1990s, the rising prevalence of disease was documented through a detectable increase in hospital admissions over time.3 A decade later, in Mangalore, an industrial port city in South West India, a population-based prevalence study was conducted between 2011 and 2013.4 Age-standardized prevalence of MS relative to the world population was 7.8 per 100,000 people. This is likely a highly conservative estimate, and in our populous nation of approximately 1.4 billion, there is the possibility of approximately 110,000 people with MS. These figures align with the estimated prevalence of 106,600 people (83,800-130,300) reported by the Global Burden of Disease studies in India (2009-2019).5 Earlier literature suggested that optic nerve and spinal cord involvement was significant among admitted people with MS. However, after the availability of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibody IgG testing, it became clear that this involvement was more likely to signify neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders rather than MS.6 Overall, the clinical presentation of MS in India is similar to that seen in the West.6,7

MS Care Challenges in India

There are approximately 2500 neurologists in India (approximately 1 neurologist per 1 million people).8 Most practice in large metropolitan cities, whereas most Indians live in rural and semirural regions, making access to quality neurological care extremely challenging. Subspecialty training is in its infancy, and there are few qualified neuroimmunologists in the country. The diagnosis of demyelinating disorders is often made in a general neurology practice. Availability of MRI scanners has improved but is limited to teaching and corporate hospitals. Special tests such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) oligoclonal band testing and fixed cell-based assays for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) IgG and AQP4-IgG testing are available through commercial laboratories that have collection sites in different parts of India as well as a few laboratories attached to academic centers. The costs and availability vary between cities and hospital settings.

Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are available and include interferon beta, glatiramer acetate, dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera; Biogen), teriflunomide (Aubagio), fingolimod (Gilenya), natalizumab (Tysabri; Biogen), and ocrelizumab (Ocrevus; Roche), which are mostly imported. More than 70% of patients in low/middle-income countries cannot access these due to the high costs.9 In India, less than 40% of the population has insurance coverage and most treatments are out-of-pocket expenditures.10 Most insurance providers also do not cover MS treatments. The few that do require a coverage period of 5 years before they will pay for the treatments.

Currently, Indian companies manufacture generics for fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate, and teriflunomide, which are cheaper than the original formulations.11 There are several manufacturers of the rituximab biosimilar, which has been used in MS therapy.12 In 2023, the World Health Organization approved the inclusion of 3 DMTs—rituximab, cladribine, and glatiramer acetate—on the Essential Medicines List, but this has not yet been implemented in India.13

Diagnostic delays and lack of affordable care make it impossible for the majority of Indian people with MS to initiate and sustain treatment. In addition, there are recurring costs for hospitalizations, MRI scans, follow-up visits, and disability-related services that take a toll on low- and middle-income families.

The Mangalore Demyelinating Disease Registry (MANDDIR): Addressing the Challenges of MS Care in South West India

MANDDIR began in 2011 as a hospital-based registry at K S Hegde Medical Academy, a teaching hospital at a private university in the coastal city of Mangalore in India. I started and continue to manage the registry with help from a rotating pool of junior neurologists, trainees, and a dedicated nurse coordinator. The neurophysiology technicians (n = 3) and physiotherapists (n = 2) who work on MANDDIR are permanent hospital employees and integral to the smooth functioning of our registry. Our multispecialty, 1000-bed hospital has a single MRI scanner (1.5T) run by general radiologists and technicians. A dedicated demyelination protocol to acquire patient images was developed by the MANDDIR team in conjunction with the radiologists. The scanner works 24 hours a day and 7 days a week, and the time to obtain an appointment is less than 24 hours. All images are stored on a cloud-based system and are available immediately.

In the initial years, MANDDIR included patients identified by our population-based survey (2011- 2013).4 Over the ensuing years (2011 to present), the registry has expanded to include patients within a radius of 500 km2 from Mangalore. Patients from other regions often enroll after being referred by their treating doctors or patient support groups or after an online search for an MS specialist. Currently, our registry has approximately 1550 patients, including 750 people with MS. A majority have low (annual family income < $6000) or middle income (annual family income ≥ $6000 -$35,000).

Patient-Friendly Initiatives for Outpatient and Inpatient Care

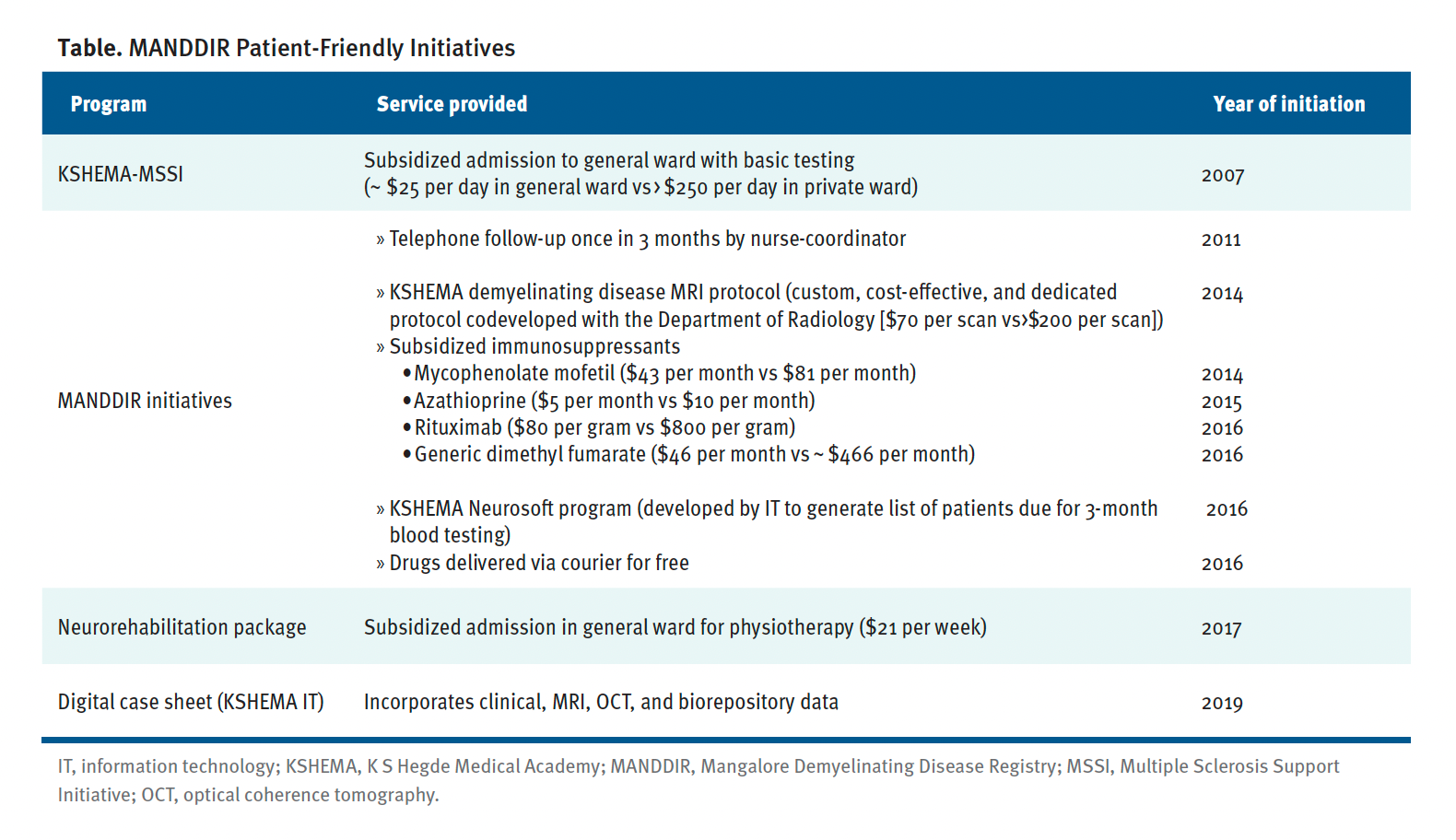

Our teaching hospital is based in rural Mangalore and offers subsidies for investigations and admission unlike the private or corporate hospitals in the area. In consultation with the hospital administrators, several patient-friendly initiatives were put in place to further reduce the cost of inpatient care and testing, including MRIs (Table).

Table. MANDDIR Patient-Friendly Initiatives

In our registry-affiliated research center, we have a small diagnostic wing where our research staff perform CSF oligoclonal band testing and live cell-based assays for MOG-IgG and AQP4-IgG testing. We were able to upgrade our electrophysiology laboratory with the purchase of a visual evoked potential machine and an optical coherence tomography unit. Charges are nominal for the reports generated from these units.

Through philanthropic donations, we developed an independent neurorehabilitation center affiliated with our registry. Our therapists have developed novel ways to engage patients and their primary caregivers during rehabilitation sessions. These include but are not limited to making video clips of their exercise program on smartphones and periodically supervising the same through WhatsApp video calls after the patients are discharged from the hospital. Because our center is based in a multispecialty hospital, the services of other departments such as psychiatry, psychology, and urology are also used for treatment of MS-related comorbidities.

Efforts to Decrease Treatment Costs

Our negotiations with pharmaceutical companies allow us to purchase drugs at a discounted price (Table). It is also possible to stock generic versions of DMTs, which are significantly cheaper than the original formulations, in our pharmacy. In addition, immunosuppressants such as generic azathioprine (AZA) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) were made available to us at subsidized prices, including, recently, the biosimilar of rituximab. Treatment costs are reduced to less than one-third of nonsubsidized therapies (Table). We deliver drugs via courier at no cost to patients who cannot visit our center. They pay our hospital for the medications online through phone-based money transfer apps or by direct bank transfer.

Remote Monitoring

All registry patients are encouraged to call our personnel on a dedicated phone line. Personnel calls are also able to receive patient reports via WhatsApp. Patients are encouraged to send prescriptions from local physician visits, soft copies of old MRI scans, and prior admission records attached to WhatsApp or email messages before their scheduled visit. Our information technology department has developed a simple, user-friendly app for MANDDIR that helps our coordinator track patients due for routine tests. Nearly 1100 patients in our registry are on regular follow-up either in person or via telephone, including 560 people with MS. Nearly 55% of patients on follow-up are adherent with medications. Among those who discontinued treatment, financial constraints, perceived lack of response, and a preference for alternative medicines were cited as reasons.

Efforts to Improve the Knowledge Gap

With informed consent from patients and permission from our institutional ethics committee, we have published about our experiences. Our epidemiological survey in urban Mangalore determined the prevalence of MS in South West India.4 Findings from genetic susceptibility studies showed close similarity with Western populations.14,15 Findings from our environmental association studies suggested that urban living, higher education, and family income were associated with MS.16 Infection with Helicobacter pylori correlated negatively in patients compared with matched controls and suggested a protective role.16,17

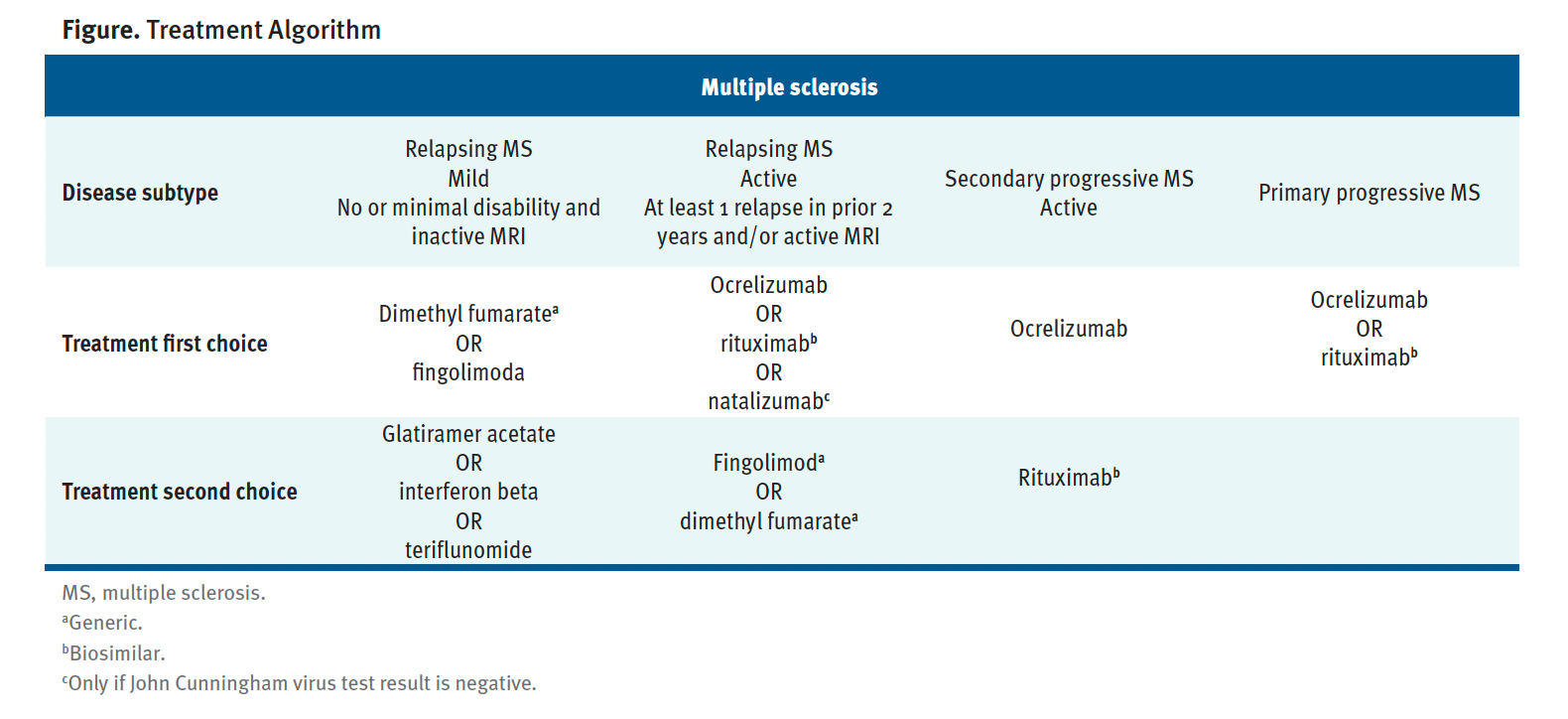

Based on MANDDIR experiences, treatment algorithms have been presented at national and regional meetings and published (Figure).

Figure. Treatment Algorithm

DMT choice was primarily driven by financial status. Those who had milder disease opted for generic oral medications. Rituximab was reserved for more aggressive disease. Though original formulations such as dimethyl fumarate, natalizumab, and ocrelizumab are marketed in India, none of our patients could afford these DMTs. We have highlighted the need to incorporate off-label therapies in the MS management algorithm.18 These included the effective use of MMF and AZA early in the disease course19,20 and relaxing the interval of rituximab infusions.21

Our experience in the management of our registry was tested during the COVID-19 pandemic.22 More than 600 patients remained in telephone contact during this time, and we were able to monitor treatment adherence, deliver medications via courier, and provide advice regarding vaccine safety and necessary preventive measures. A majority of our patients opted to take the mRNA vaccine and continued MS therapies (including off-label medications) successfully, and we had no COVID-19–related deaths.

Against this backdrop, the publicity generated by MANDDIR and the support of a neurologist with interest in autoimmune disorders made it possible to lobby the Indian Academy of Neurology to start a subsection for autoimmune disorders. Annual meetings are conducted under its auspices and are attended by a national audience of neurologists and allied specialists. Currently, we run a recognized fellowship course in clinical neuroimmunology and conduct yearly workshops for trainees and new graduates. Efforts are ongoing to establish a national database of MS and related disorders.23

Despite many challenges, MANDDIR developed into a sustainable model of care for people with MS through a collaborative effort with several stakeholders, including administrators, pharmaceutical companies, and philanthropists. Off-label therapies and subsidized care are at the core of our management strategy. MANDDIR is, above all, a patient-centric, physician-driven effort by a small team, and I strongly believe that our model is replicable in other low-income settings.

References

Singh B, Isaiah P, Chandy J. Multiple sclerosis (studies on sixteen cases). Neurology. 1954;1:49-59.

Bharucha EP, Umarji RM. Disseminated sclerosis in India. Int J Neurol. 1961;2:182-188.

Syal P, Prabhakar S, Thussu A, Sehgal S, Khandelwal N. Clinical profile of multiple sclerosis in north-west India. Neurol India. 1999;47(1):12-17.

Pandit L, Kundapur R. Prevalence and patterns of demyelinating central nervous system disorders in urban Mangalore, South India. Mult Scler. 2014;20(12):1651-1653. doi:10.1177/1352458514521503

India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Neurological Disorders Collaborators. The burden of neurological disorders across the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease study 1990-2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(8):e1129-e1144. doi:10.1016 /S2214-109X(21)00164-9

Singhal BS, Advani H. Multiple sclerosis in India: an overview. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015;18(suppl 1):S2-S5. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.164812

Pandit L. Insights into the changing perspectives of multiple sclerosis in India. Autoimmune Dis. 2011;2011:937586. doi:10.4061/2011/937586

Singh G, Khadilkar S, Jayalakshmi S. The future of neurology in India. World Neurology. January 13, 2020. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://worldneurologyonline.com/article /the-future-of-neurology-in-india

Essential medicines for MS. Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Updated January 2, 2025. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.msif.org/essential-medicines

Bhatia M, Singh DP. Health sector allocation in India’s budget (2021-2022): a trick or treat? Int J Commun Soc Dev. 2021;3(2):177-180. doi:10.1177/25166026211017338

Sehrawat M, Madhusudhan SK, Bakkappa SD, Devendrappa SL. Study to compare the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of various disease modifying drugs in the management of multiple sclerosis in India- an observational study. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2023;26(6):895-901. doi:10.4103/aian.aian_467_23

Mathew T, John SK, Kamath V, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in multiple sclerosis: experience from a developing country. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;43:102210. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2020.102210

Yamout BI, Viswanathan S, Laurson-Doube J, Sokhi D. Disease-modifying therapies enter the World Health Organization Essential Medicines List: a victory now requiring a roadmap of implementation. Mult Scler. 2024;30(1):3-6. doi:10.1177/13524585231205970

Pandit L, Ban M, Beecham AH, et al. European multiple sclerosis risk variants in the South Asian population. Mult Scler. 2016;22(12):1536-1540. doi:10.1177/1352458515624270

Pandit L, Malli C, Singhal B, et al. HLA associations in South Asian multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2016;22(1):19-24. doi:10.1177/1352458515581439

Malli C, Pandit L, D’Cunha A, Mustafa S. Environmental factors related to multiple sclerosis in Indian population. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124064. doi:10.1371/journal .pone.0124064

Malli C, Pandit L, D’Cunha A, Sudhir A. Helicobacter pylori infection may influence prevalence and disease course in myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody associated disorder (MOGAD) similar to MS but not AQP4-IgG associated NMOSD. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1162248. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1162248

Pandit L. Fair and equitable treatment for multiple sclerosis in resource-poor regions: the need for off-label therapies and regional treatment guidelines. Mult Scler. 2021;27(9):1320-1322. doi:10.1177/13524585211028806

Pandit L, Mustafa S, Malli C, D’Cunha A. Mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a preliminary report. Neurol India. 2014;62(6):646-648. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.149390

Pandit L, Mustafa S, Sudhir A, Malapur P, D’Cunha A. Determining effectiveness of “off-label therapies” for multiple sclerosis in a real-world setting. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2024;27(3):250-253. doi:10.4103/aian.aian_114_24

Alva S, Pandit L, Sudhir A, D’Cunha A. Relaxing rituximab infusion intervals may be a cost effective and safe recommendation for management of multiple sclerosis in resource poor settings: PACTRIMS 2024. Mult Scler. 2024;30(9):NP1-NP29. doi:10.1177/13524585241269222

Pandit L, Sudhir A, Malli C, D’Cunha A. COVID-19 infection and vaccination against COVID-19: impact on managing demyelinating CNS disorders in Southern India-experience from a demyelinating disease registry. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;66:104033. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2022.104033

IMSRN Collaborators. The Indian Multiple Sclerosis and Allied Demyelinating Disorders Registry and Research Network (IMSRN): inception to reality. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2024;87:105627. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2024.105627