Publication

Theme Article

International Journal of MS Care

Multiple Sclerosis in the Middle East and North Africa: Perspectives and Challenges

From the Université Saint Joseph de Beyrouth and Hôtel-Dieu de France Hospital, Beirut, Lebanon (JC, GM); the Neurology Institute, Harley Street Medical Center, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (JM, BY); the Department of Neurology, Clinical Investigation Centre Neurosciences and Mental Health LR 18SP03, Razi University Hospital–Manouba, Tunis, Tunisia (SM); the Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, University of Tunis El Manar, Tunisia (SM); and the Department of Neurology, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (GM). Correspondence: Gabrielle Macaron; 1000 St Denis Street, Montreal, QC, Canada, H2X 0C1; email: gabrielle.macaron@umontreal.ca; gabrielle.macaron.med@ssss.gouv.qc.ca

Abstract

The prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS) is increasing in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), in part due to better access to earlier diagnosis. Many MENA countries are now considered to fall in moderate to high MS risk zones. MS in MENA populations occurs at a younger age and is more severe, specifically in North African populations. Large disparities in MS care have been observed among MENA countries. Access to care remains a significant obstacle in countries with low incomes, active wars, and a large number of refugees. The MENA MS population could serve as participants in the evaluation of several genetic, epigenetic, and environmental risk factors for MS. Indeed, low vitamin D levels due to reduced sun exposure in hijab-wearing women might explain the striking rising prevalence in Iran after the Islamic revolution, and the prevention of MS with vitamin D could be evaluated in this community. Moreover, because immigration is part of the history of MENA populations, it can serve as an archetype for the study of the impact of immigration on MS risk and severity. Unfortunately, MENA populations are underrepresented in clinical trials, limiting our understanding of this group. However, with the creation of the Middle East and North Africa Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis and the emergence of highly specialized MS centers in several countries, better access to care and collaborative research efforts are expanding.

Several genetic and environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis (MS) have been identified, such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex (particularly with HLA-DRB1*15:011), reduced sun exposure and low vitamin D,2 and Epstein-Barr virus infection.3 Other environmental risk factors include smoking, obesity, diet, and microbiome.1 Although the prevalence of MS varies along a geographic gradient, MS prevalence has increased in every world region in the past 2 decades. According to the Atlas of MS data,4 the global MS prevalence increased from 29.26 to 43.95 per 100,000 people between 2013 and 2020, with the highest MS prevalence recorded in North America (approximately 300 per 100,000) and European countries (142.8 per 100,000), and the lowest in Western Pacific regions (4.79 per 100,000). A rapid increase in the female-to-male ratio has also been observed over the past century, supporting an interaction of sex and environmental factors on the development of MS in women.5 Genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factor interaction is complex, but explains the differences in MS risk, phenotype, and severity across different populations. Phenotypic differences between predominant ethnic categories in the United States and Europe have been studied, but unfortunately, the Arab population of individuals with MS in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has received little research interest. The clinical and demographic aspects of MS in the MENA region are, therefore, less characterized. The aim of this narrative review is to highlight epidemiological and phenotypic characteristics of MS in the MENA region, discuss the main challenges in accessing care, and highlight research questions relevant to the MENA population.

Epidemiological Particularities of MS in the MENA Region

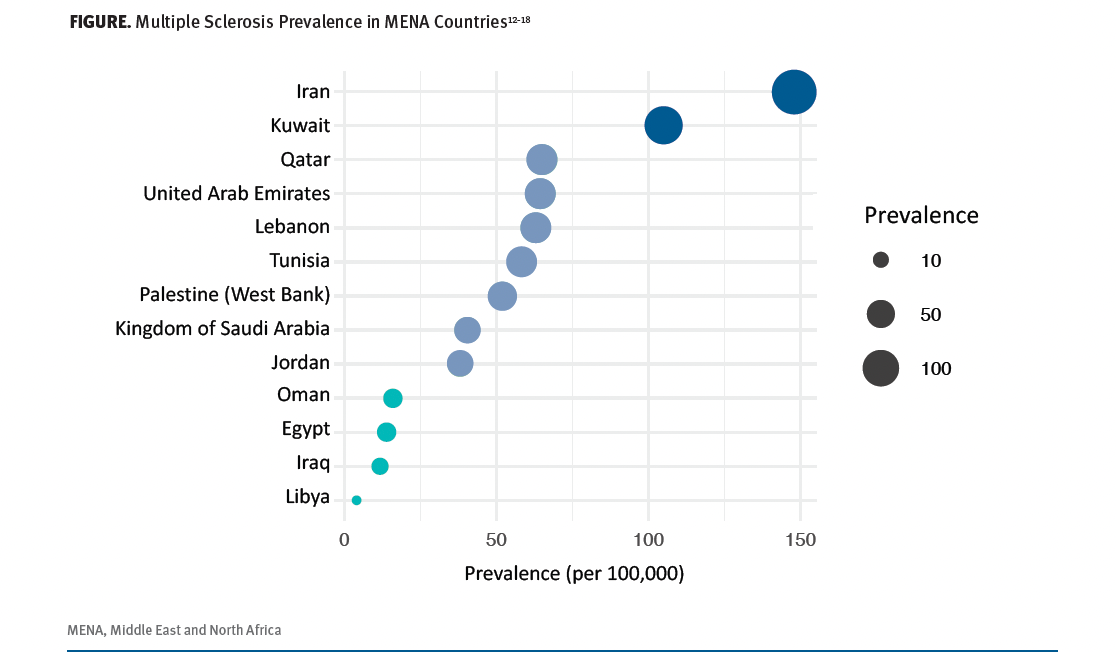

Middle Eastern populations have heterogeneous ethnic origins mixed with Western (Anatolian, Levantine) and Eastern (Iranian, Caucasian) ancestry, with a relatively homogeneous racial background and a common Arabic language.6 It is of note that genetic differences between different populations of the same race might sometimes be greater than between different races. North Africans, natively Berbers, have received genetic contributions from their Middle Eastern, European, and sub-Saharan/African ancestry.7 The MENA region is located at a latitude of 12° to 42° and a longitude of 35° to 54°.8 Based on epidemiological studies prior to 2000, the MENA region was considered to be in the low-moderate MS prevalence zone, with rates ranging between 3 and 20 cases per 100,000 persons.9,10 However, consistent with the rising incidence and prevalence rates worldwide, a similar increase has been seen in the MENA region. This may be due to advances in MS diagnosis because of, among other factors, increased access to MRIs and specialized MS centers, and/or earlier diagnosis with revised diagnostic criteria, which have been validated in MENA populations.11 However, aging of the general population and increased urbanization (implying less sun exposure and increased obesity, stress, and smoking) might also contribute to an increase in MS incidence.12 The most recent reported MS prevalence rates in different MENA countries are shown in the Figure.12-18 MS prevalence is highly variable, with the lowest rates reported in Libya (data from 1985), Oman, and Iraq, and the highest rates in Iran, with a 2017 prevalence of 148 per 100,000.12 Familial MS is particularly prevalent in Iran.19 Interestingly, the MS incidence in Iran has been steadily increasing since 1990, faster than the rise in other MENA and Western European countries.20 Lebanon has also seen increasing prevalence. In 2018, the prevalence was 62.9 per 100,000 people, placing Lebanon in the category of moderate to high risk for MS.14 Similarly, the 2019 crude prevalence rate in the West Bank of Palestine was 51.9 per 100,000, with an overall increase between 2010 and 2019.16 In Kuwait, the crude 2018 prevalence was 105 per 100,000, an increase of 1.6 times compared with 2013.13 In Saudi Arabia, the 2018 prevalence was 40.4 per 100,000, and 62 per 100,000 when accounting for Saudi nationals only.17 In Tunisia, the 2020 prevalence was 58.3 per 100,000 vs 20.2 per 100,000 in 2000.21 In Oman, the 2021 prevalence estimate was 15.9 per 100,000, significantly higher than previously reported (< 5 per 100,000).14 A similar increase was seen in Iraq (11.7 per 100,000).18 However, the latter estimates were based on hospital registries, which are less reliable than national registries. Little is known about the prevalence and incidence of MS in several Arab countries, including Algeria and Syria.

Figure. Multiple Sclerosis Prevalence in MENA Countries12-18

Phenotypic Particularities of MS in the MENA Region

Clinical MS onset tends to occur at an earlier age in MENA patients, most commonly 25 to 29 years of age.20 In an epidemiological meta-analysis carried out in 2015, the mean age at onset was 28.5 years, ranging from 25 years in Kuwait to 32 years in Iran and Saudi Arabia.22 Similarly, in 2020, Yamout et al reported a mean age at onset of 27.8 years across several MENA countries, with 60% manifesting before age 30 and 17% before age 20.12 In comparison, the mean age at onset in predominantly White populations from European and North American studies was 32 to 34 years of age.23-27 An earlier age of onset in North African descendants living in France compared with White French residents was also observed.28

According to the Middle East and North Africa Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (MENACTRIMS) registry, the presenting symptoms were optic or spinal in two-thirds of cases. MS onset was relapsing in 96% and progressive in only 3.2% of cases.12 The clinical presentation, severity, and disability progression vary widely. In North Africa, people with MS tend to have more severe disease, more incomplete recovery after first relapse, and more rapidly progressing disability, despite earlier onset and often equal access to care when compared with European cohorts.12,27 This has been consistently observed in MS registries from Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco.27-29 In other countries, such as Lebanon, Egypt, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates, a milder phenotype is observed, comparable to the MS population in Western countries, at least based on the large MSBase registry.12,30,31 However, symptoms are reportedly more severe and time to secondary progression (SPMS) is shorter in Muslim and Druze Arabs when compared with Christian Arabs in the region. This further emphasizes the importance of genetic factors, as religion is a relatively fixed heritage in the region.30 SPMS risk seems higher in Oman, Iran, and Tunisia, according to a large (> 50,000 patients) worldwide MSBase study, even after taking into account disability, relapse rate, national prevalence, government health expenditure, and time on moderate- to high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies (DMTs).32 Of note, Canada was among the countries with the highest SPMS risk. However, there was no association between MENA ethnicities and risk of SPMS in this study. The prevalence of primary progressive MS appears to be the highest in Saudi Arabia.31 Studies addressing biologic and radiologic biomarkers of MS in the MENA region are still missing from the current literature. Serum and cerebral spinal fluid neurofilament light chains and central vein sign test results seem to be comparable to Western cohorts in 2 studies from Tunisia and Egypt.33,34

Access to Care and Care Inequities

Access to MS care, especially DMTs, varies widely across MENA countries. Between 2009 and 2018, platform injectable therapies were the most commonly used DMTs in Egypt, Iran, and Turkey (53%-86%), whereas oral DMTs and monoclonal antibodies were most commonly used in Kuwait, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates (59%-87%).31 Specifically, fingolimod was the most widely accessible oral DMT in almost all MENA countries.34 Access to DMTs for patients with SPMS was limited to a few countries such as Kuwait and Egypt. Consistent with the global increase in prescribing high-efficacy DMTs, a similar trend was observed across the MENA region but at a slower rate. These differences may be attributable to variabilities in gross domestic product per capita, as countries with higher income have better access to newer (and more expensive) treatments.31

In addition to inequities in socioeconomic status, political unrest, wars, and refugee crises have further widened the gap among countries. The most recent data based on the Atlas of MS indicate widespread use of off-label DMTs such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and rituximab.4 The disparities are further highlighted when considering the case of Sudan, for example, which has no access to any approved DMTs and no access to off-label, high-efficacy DMTs. In 40% of MENA countries (but no Gulf countries), new DMTs are either not registered or not fully reimbursed by governments, and the high cost of treatment is the most significant barrier to care.35 Other barriers include substantial co-payments (coverage by national health system or insurance), lack of MRI access, and paucity of MS specialists, all of which can equally impede care. Indeed, significant difficulties for consistent DMT access due to supply and reimbursement concerns were observed in 56% of MENA countries, specifically in low-income countries and those experiencing political unrest.14

Displacement, which has long been an outcome of war and conflicts in the MENA region, has resulted in a sizable number of refugees in countries such as Jordan and Lebanon, posing an unparalleled burden on their health care systems. As of 2023, Lebanon, a country of 4.5 million Lebanese citizens, is hosting 1.5 million Syrians and 300,000 Palestinians refugees, 90% of whom live in extreme poverty, according to the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees. These 2 groups make up 40% of the population, making Lebanon the country with the highest number of refugees per capita worldwide. DMT access is limited for refugees, with sporadic supply of interferons from the Syrian Ministry of Health (requiring possibly unsafe travel to Syria) and from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. Host governments are also unable to carry the cost of DMTs for refugees. To improve access, key MS centers in Lebanon have secured funds from various entities to offer first-line rituximab free of charge to refugees.36 This is in a country where 61.7% of Lebanese people with MS reported an interruption in or inability to access DMTs, with a significant impact on their quality of life.37

In spite of these struggles, optimism prevails with the establishment of multidisciplinary collaborative MS centers of excellence in several countries to refine MS management in the MENA region.38 Another positive step is the addition of 3 DMTs (glatiramer acetate, cladribine, rituximab) on the World Health Organization Essential Medicines List; this is a significant milestone for people with MS across the globe, but it does not necessarily imply real-world feasibility in countries with socioeconomic challenges and political instability.39

Collaborative Efforts in the MENA Region

Founded in 2012, MENACTRIMS aims to improve MS care and research efforts among MENA MS specialists. Its founding led to an increase in the number of specialized MS centers and a rising interest in participation in clinical trials.14 The MENACTRIMS registry, a regional MSBase substudy, was created through a collaborative effort in 2016.12 Other noteworthy endeavors include the publication of the MENACTRIMS treatment guidelines40; the development of criteria and evaluation processes for certification of MS centers; the organization of the annual MENACTRIMS congress and associated workshops and educational forums; and the availability of annual research grants, fellowship grants, and internships for physiotherapists in European MS centers. In collaboration with the International Organization of Multiple Sclerosis Nurses and the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, annual MS certification exams for MS nurses and other MS specialists have also been offered, leading to an increased the number of certified health care providers in the MENA region.

Contemporary Topics Relevant to the MENA Region

Sun Exposure, Hijab, and MS Risk

Vitamin D deficiency during childhood and adolescence is a risk factor for MS.41 The majority of Arab countries are predominantly Muslim, and women wearing the hijab or niqab is a common practice that leads to less sun exposure and, consequently, lower vitamin D levels. This has been observed in several countries. A recent study evaluating low vitamin D levels in Palestinian young adults showed that the majority of men had sufficient/optimal levels vs only 7% of women (of whom 98% wear the hijab).42 After the Iranian revolution of 1979, all Iranian women were legally required to wear the hijab and loose-fitting clothes covering their arms and legs. Between 1989 and 2006, Iran recorded an 8.3-fold increase in the incidence of MS with an increasing female predominance.43 It is highly likely that this substantial and rapid rise may be due to genetic changes and may be linked to reduced sun exposure and associated low vitamin D levels.43 Early vitamin D repletion as a primary prevention strategy may be considered in the hijab-wearing population, but its effectiveness in reducing MS incidence requires further investigation.

Immigration

The MENA population could serve as an archetype for the study of immigration and the understanding of the pathophysiological bases of MS, particularly the interplay among genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors on MS risk and phenotype. Several environmental factors for MS are similarly observed between MENA and Western countries.44,45 Although results are heterogeneous across studies, it is generally accepted that immigration from high- to low-risk regions reduces MS risk if relocation occurs before individuals are 15 years of age.46 Genetic factors may also have a determining role in the occurrence and phenotype of the disease. Seyman et al evaluated MS characteristics in patients of MENA descent residing in the Canadian province of Ontario.47 These patients displayed higher disease severity and greater disability progression despite similar annualized relapse rates and new/enlarging T2 lesions over time when compared with MS patients of European descent.47 Sidhom et al compared disability progression in first- and second-generation North Africans living in France with those living in Tunisia, and with White patients born and living in France.27 Second-generation North African patients had the most severe disease despite no difference in access to care, delay in diagnosis, or use of higher efficacy DMTs.27 In fact, they were more likely to be diagnosed early and treated with high-efficacy DMTs compared with other groups, probably secondary to their more severe phenotype at disease onset. North Africans living in Tunisia had less severe disease compared with those living in France, which highlights the impact of environmental factors. These immigration studies have substantial potential to inform on the importance of epigenetics and environmental factors associated with MS pathogenesis, risk, and prognosis.

DMT Use in Special Populations

According to a large 2018 retrospective study using data from the MENACTRIMS registry, almost half of people with MS in the MENA region were treated with interferon beta. Fingolimod was the most prescribed oral DMT (14.9%), followed by dimethyl-fumarate (4.8%). Natalizumab was used in 8.5% of patients, whereas CD20-targeted therapies were used in nearly 6% of patients.12 Of note, cladribine was recently recommended as a first-line agent in the treatment of moderately to highly active disease in the MENACTRIMS 2023 consensus for treatment of relapsing-remitting MS.40 Although cladribine is a good therapeutic option in countries with poor access to infusion centers and few resources, the extent of its use in the MENA region is not sufficiently reported.12,48 Evidence-based data on the effectiveness and tolerability of these DMTs in the MENA population are lacking because randomized controlled trials predominantly recruit White patients, and, when enrolled in trials, patients of Lebanese, Egyptian, and other MENA ancestry are often classified as White. Indeed, the 1997 US Census defined a White person as “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.”49 Extrapolating from other studies evaluating DMT effectiveness in different groups, known racial and ethnic disparities in treatment response are observed. For instance, Black people have a poorer DMT response compared with White people. Despite similar DMT exposure, Black people had a higher risk of disability progression and more frequent treatment-related adverse events compared with White people and Hispanic people.50 The choice of DMT may also be influenced by race and ethnicity. In the above-mentioned study comparing disease severity among North Africans with MS living in France and Tunisia to that among White patients, earlier treatment with higher-efficacy DMTs did not alter the likelihood of having more severe disease in those with North African ancestry.27 Recent supporting evidence points toward a decreased SPMS risk with earlier high-efficacy treatment,32,51 hence, this approach should be considered in populations at risk for severe disease course, such as those in North Africa in particular, until better effectiveness data is available.

Conclusions and Future Directions

As MS prevalence rises in the MENA region, there is significant variability in disease severity due to disparities in access to treatment and diverse socioeconomic, genetic, and environmental factors across the region. A lack of comprehensive MS registries across all countries limits the applicability of the observed data to the MENA region as a whole. Moreover, variations in health care systems and the structure of epidemiological research across different countries may contribute to substantial confounders. It is possible, for instance, that patients with severe presentations are predominantly referred to specialized centers reporting these studies, causing a selection bias. Collaborative efforts in the region are pivotal to enhance standards of care and research to address these challenges, as well as the inclusion of patients from diverse ethnicities and races in randomized controlled trials.

Conflicts of Interest: Jad Costa, MD, reports no conflicts of interest. Joelle Massouh, MSCN, has received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards from AbbVie, Biogen, Biologix, Janssen, Lundbeck, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi. Saloua Mrabet, MD, received a Middle East and North Africa Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis clinical fellowship grant in 2020. Bassem Yamout, MD, received lecture honoraria from Bayer, Biogen, Genpharm, Genzyme, Merck-Serono, and Novartis; research grants from Bayer, Biogen, Merck-Serono, Novartis, and Pfizer; and advisory board honoraria from Bayer, Biogen, Genpharm, Genzyme, Merck-Serono, and Novartis. Gabrielle Macaron, MD, received an Innovations in Well- Being Award from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society/International Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Alliance (grant #PA-2304-41062) (2024-2025). She has been on advisory boards for Genentech-Roche, Merck/EMD Serono, and Novartis, and has participated in educational programs for Biogen, Johns Hopkins e-Literature review, MedEdge, NeurologyLive, and Novartis.

References

Ward M, Goldman MD. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis. Contin Minneap Minn. 2022;28(4):988-1005. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000001136

Hayes CE, Cantorna MT, DeLuca HF. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1997;216(1):21-27. doi:10.3181/00379727-216-44153a

Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022;375(6578):296- 301. doi:10.1126/science.abj8222

Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler. 2020;26(14):1816-1821. doi:10.1177/1352458520970841

Orton SM, Herrera BM, Yee IM, et al. Sex ratio of multiple sclerosis in Canada: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(11):932-936. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70581-6

Martiniano R, Haber M, Almarri MA, et al. Ancient genomes illuminate Eastern Arabian population history and adaptation against malaria. Cell Genomics. 2024;4(3):100507. doi:10.1016/j.xgen.2024.100507

Lucas-Sánchez M, Fadhlaoui-Zid K, Comas D. The genomic analysis of current-day North African populations reveals the existence of trans-Saharan migrations with different origins and dates. Hum Genet. 2023;142(2):305-320. doi:10.1007/s00439-022-02503-3

CORDEX. Region 13: Middle East North Africa (MENA). Accessed June 3, 2025. https://cordex.org/domains/cordexregion-mena-cordex/

al-Din AS, el-Khateeb M, Kurdi A, et al. Multiple sclerosis in Arabs in Jordan. J Neurol Sci. 1995;131(2):144-149. doi:10.1016/0022-510x(95)00092-g

al Rajeh S, Bademosi O, Ismail H, et al. A community survey of neurological disorders in Saudi Arabia: the Thugbah study. Neuroepidemiology. 1993;12(3):164-178. doi:10.1159/000110316

Souissi A, Mrabet S, Nasri A, et al. Multiple sclerosis 2017 McDonald criteria are also relevant for Tunisians. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;43:102161. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2020.102161

Yamout BI, Assaad W, Tamim H, Mrabet S, Goueider R. Epidemiology and phenotypes of multiple sclerosis in the Middle East North Africa (MENA) region. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020;6(1):2055217319841881. doi:10.1177/2055217319841881

Alroughani R, AlHamdan F, Shuaibi S, et al. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis continues to increase in Kuwait. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;32:74-76. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2019.04.033

Zeineddine M, Hajje AA, Hussein A, El Ayoubi N, Yamout B. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Lebanon: a rising prevalence in the Middle East. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;52:102963. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2021.102963

Al-Senani M, Al-Salti A, Nandhagopal R, et al. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in the Sultanate of Oman: a hospital based study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;53:103034. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2021.103034

Abuawad M, Ziyadeh-Isleem A, Alkaiyat A, et al. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in West Bank of Palestine. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;59:103686. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2022.103686

AlJumah M, Bunyan R, Al Otaibi H, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Saudi Arabia, a descriptive study. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):49. doi:10.1186/s12883-020-1629-3

Hassoun HK, Al-Mahadawi A, Sheaheed NM, Sami SM, Jamal A, Allebban Z. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Iraq: retrospective review of 4355 cases and literature review. Neurol Res. 2022;44(1):14-23. doi:10.1080/01616412.2021.1952511

Salehi Z, Almasi-Hashiani A, Sahraian MA, et al. Epidemiology of familial multiple sclerosis in Iran: a national registry-based study. BMC Neurol. 2022;22(1):76. doi:10.1186/s12883-022-02609-1

Abbastabar H, Bitarafan S, Mohammadpour Z, Mohammadianinejad SE, Harirchian MH. The trend of incidence, prevalence, and DALY of multiple sclerosis in the Middle East and Northern Africa region compared to global, West Europe, and Iran’s corresponding values during 1990-2017: retrieved from global burden of diseases data. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;52:102949. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2021.102949

ECTRIMS 2022—ePoster. Mult Scler J. 2022;28(suppl 3):692-945. doi:10.1177/13524585221123682

Heydarpour P, Khoshkish S, Abtahi S, Moradi-Lakeh M, Sahraian MA. Multiple sclerosis epidemiology in Middle East and North Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;44(4):232-244. doi:10.1159/000431042

Ascherio A, Munger KL. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: from risk factors to prevention-an update. Semin Neurol. 2016;36(2):103-114. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1579693

Gbaguidi B, Guillemin F, Soudant M, Debouverie M, Mathey G, Epstein J. Age-period-cohort analysis of the incidence of multiple sclerosis over twenty years in Lorraine, France. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1001. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-04836-5

Prosperini L, Lucchini M, Ruggieri S, et al. Shift of multiple sclerosis onset towards older age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2022-329049

Romero-Pinel L, Bau L, Matas E, et al. The age at onset of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis has increased over the last five decades. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;68:104103. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2022.104103

Sidhom Y, Maillart E, Tezenas du Montcel S, et al. Fast multiple sclerosis progression in North Africans: both genetics and environment matter. Neurology. 2017;88(13):1218-1225. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000003762

Araqi-Houssaini A, Lahlou I, Benkadmir Y, et al. Multiple sclerosis severity score in a cohort of Moroccan patients. Mult Scler. 2014;20(6):764-765. doi:10.1177/1352458513506504

Hecham N, Nouioua S, Sifi Y, et al. Multiple sclerosis: progression rate and severity in a multicenter cohort from Algeria. Mult Scler. 2014;20(14):1923-1924. doi:10.1177/1352458514543343

Bonomi S, Jin S, Culpepper WJ, Wallin MT. MS and disability progression in Latin America, Africa, Asia and the Middle East: a systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;51:102885. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2021.102885

Moradi N, Sharmin S, Malpas C, et al. Utilization of multiple sclerosis therapies in the Middle East over a decade: 2009-2018. CNS Drugs. 2021;35(10):1097-1106. doi:10.1007/s40263-021-00833-w

Sharmin S, Roos I, Simpson-Yap S, et al. The risk of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis is geographically determined but modifiable. Brain J Neurol. 2023;146(11):4633-4644. doi:10.1093/brain/awad218

Abdel Ghany H, Karam-Allah A, Edward R, Abdel Naseer M, Hegazy MI. Sensitivity and specificity of central vein sign as a diagnostic biomarker in Egyptian patients with multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:1985-1992. doi:10.2147/NDT.S377877

Mrabet S, Sghaier I, Souissi A, et al. Neurofilaments light chains as a diagnostic and predictive biomarker for Tunisian multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2024;91:105901. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2024.105901

Zeineddine M, Al-Hajje A, Salameh P, et al. Barriers to accessing multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies in the Middle East and North Africa region: a regional survey-based study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;79:104959. doi:10.1016 /j.msard.2023.104959

Zeineddine MM, Yamout BI. Treatment of multiple sclerosis in special populations: the case of refugees. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020;6(1):2055217319848466. doi:10.1177/2055217319848466

Ismail G, Issa M, El-Hajj T, et al. Quality of life, knowledge and access to treatment in times of economic crisis in Lebanon. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;71:104328. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2022.104328

Khoury SJ, Tintore M. Multiple sclerosis in the Middle East and North Africa region. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2020;6(1):2055217319895540. doi:10.1177/2055217319895540

Yamout BI, Viswanathan S, Laurson-Doube J, Sokhi D. Disease-modifying therapies enter the World Health Organization Essential Medicines List: a victory now requiring a roadmap of implementation. Mult Scler. 2024;30(1):3-6. doi:10.1177/13524585231205970

Yamout B, Al-Jumah M, Sahraian MA, et al. Consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis: 2023 revision of the MENACTRIMS guidelines. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2024;83:105435. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2024.105435

Sangha A, Quon M, Pfeffer G, Orton SM. The role of vitamin d in neuroprotection in multiple sclerosis: an update. Nutrients. 2023;15(13):2978. doi:10.3390/nu15132978

Lenz JS, Tintle N, Kerlikowsky F, et al. Assessment of the vitamin D status and its determinants in young healthy students from Palestine. J Nutr Sci. 2023;12:e38. doi:10.1017/jns.2023.25

Pakpoor J, Ramagopalan SV. Multiple sclerosis and the Iranian revolution. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;38(2):122. doi:10.1159/000336234

Taan M, Al Ahmad F, Ercksousi MK, Hamza G. Risk factors associated with multiple sclerosis: a case-control study in Damascus, Syria. Mult Scler Int. 2021;2021:8147451. doi:10.1155/2021/8147451

Halawani AT, Zeidan ZA, Kareem AM, Alharthi AA, Almalki HA. Sociodemographic, environmental and lifestyle risk factors for multiple sclerosis development in the Western region of Saudi Arabia. a matched case control study. Saudi Med J. 2018;39(8):808-814. doi:10.15537/smj.2018.8.22864

Hawkes CH, Giovannoni G, Lechner-Scott J, Levy M, Waubant E. Multiple sclerosis and migration revisited. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;34:A1-A2. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2019.08.001

Seyman E, Jones A, Guenette M, et al. Clinical and MRI characteristics of multiple sclerosis in patients of Middle Eastern and North African ancestry residing in Ontario, Canada. Mult Scler. 2021;27(7):1027-1036. doi:10.1177/1352458520948212

Deleu D, Mesraoua B, Canibaño B, et al. Oral disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region: an overview. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(2):249-260. doi:10.1080/03007995.2018.1476334

United States Census Bureau. About the topic of race. Revised December 20, 2024. Accessed May 7, 2025. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html

Pérez CA, Lincoln JA. Racial and ethnic disparities in treatment response and tolerability in multiple sclerosis: a comparative study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;56:103248. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2021.103248

Brown JWL, Coles A, Horakova D, et al. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2019;321(2):175-187. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.20588