Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Multiple Sclerosis, Anxiety, and Depression in the United Arab Emirates

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

Depression rates in the multiple sclerosis (MS) population in the Arab world have rarely been reported despite people with MS generally having higher rates of depression. We examined depression rates in 416 people with MS versus the general population of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, and their treatment.

Methods:

A retrospective medical record review of 416 people with MS (age range, 16–80 years) followed up at four large government hospitals in Abu Dhabi was conducted to determine the percentage of people with MS diagnosed as having depression or anxiety.

Results:

The depression rate in people with MS (10.8%) was close to that in the general population of Abu Dhabi. The adjusted odds ratios of depression by selected variables showed that there was a significant difference (P = .003) between females and males in reporting depression, with more females reporting depression than males. Greater MS duration was also associated with a higher likelihood of being depressed (P = .025). The anxiety rate in the cohort (4.8%) was lower than that in the general Abu Dhabi population (18.7%).

Conclusions:

The depression rate in people with MS in Abu Dhabi was close to that of the general Abu Dhabi population, but the anxiety rate in people with MS was lower. Explanations for these low rates include possible underreporting by patients and physician factors such as time limitations in busy clinics. Cultural aspects such as strong family support systems and religious factors in this predominantly Muslim population are also possible factors that warrant further investigation.

Major depressive disorder represents a wide spectrum of illness that affects more than 16% of people in the United States and is often an associated comorbidity in other medical conditions.1 Symptoms of clinical depression affect many different aspects of a person's well-being and range from general discontent to agitation and social isolation. Although patients with chronic disease have a higher rate of depression than the general population, people with multiple sclerosis (MS) have an especially high rate of depression, with a lifetime prevalence reported to be as high as 50%.2,3 It has been shown that the incidence of depression after the onset of MS is increased fourfold and that the presence or severity of depression in MS does not correlate well with the degree of physical disability.4 Furthermore, in a long-term cohort study, depression scores were found to remain largely stable even while disability scores increased.5

Compared with other chronic diseases in patients with similar degrees of impairment, those with MS still had a higher rate of depression.6,7 Some researchers suggest that inflammatory changes resulting from the disease process may be involved in the pathogenesis of depression in patients with MS.8,9 Others have proposed that the relationship is not unidirectional. A limited study by Mohr et al10 demonstrated that treatment of depression using cognitive behavioral therapy, group psychotherapy, or sertraline had actually decreased interferon gamma production and proposed that treatment of depression may alleviate some symptoms of MS itself.

Diagnosing depression in patients with MS can be challenging because there is overlap in symptoms between clinical depression and MS, such as fatigue, psychomotor retardation, decreased concentration, and insomnia or hypersomnia. It has been suggested that this may result in an overdiagnosis of depression in patients with MS. Specifically, one study found that removing confounding symptoms such as work problems, fatigue, and concerns about health increases the accuracy of depression screening.10 However, other studies suggest that depression is both underdiagnosed and undertreated in patients with MS.11,12 Recognizing depression in those with MS can greatly affect their care because depression affects patients' ability to manage their disease and adhere to treatment. Depression is second only to coronary artery disease in the degree of functional impairment it causes compared with other causes of chronic disability.13

Although our previous paper demonstrated a prevalence rate of 64.4 of 100,000 Emiratis with MS in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (UAE), the link between MS and depression in this geographic area has not been well studied.14 In general, mental health disorders in the Arab world are stigmatized, and, therefore, prevalence estimates of these conditions are difficult to measure. Only one pilot study has been conducted on the link between depression and MS in the UAE.15 However, that study did not find an increased rate of depression, unlike several studies in other Arab countries,15,16 possibly due to the small sample size and single-center nature of the study. The present study aimed to examine these findings in a multicenter study with a larger sample size and explore the differences in depression as a function of demographic variables and disease characteristics.

Methods

Record Review

A retrospective medical record review of 416 people with MS was conducted at Tawam Hospital, Al Ain Hospital, Mafraq Hospital, and Sheikh Khalifa Medical Center in Abu Dhabi between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2016. This medical record review was an extension of a previously published epidemiologic study performed in the same hospitals that identified 510 people with MS in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi.14 Medical records reviewed for depression were those of patients with MS who had not been lost to follow-up (due to transferring care to a private medical facility or other reasons, such as death or leaving the country) during the period and for whom there was enough information in the medical record regarding MS-specific care. Each hospital's institutional review board approved the study. Each medical record was initially reviewed by a medical student (K.H. or K.B.H.) for an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code billing for depression or anxiety, mention of either depression or anxiety in any of the physician's clinical notes, or the presence of antidepressant medication. Each medical record was then reviewed again by a board-certified neurologist specializing in MS (N.S.) for confirmation. Data collected included age, sex, country of origin, MS type, age at symptom onset, type of symptom at onset, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score, and immunomodulatory therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata SE software, version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Categorical variables were tabulated as frequency (percentage) and continuous variables as mean ± SD. Simple and multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the association of depression with selected variables. In simple logistic regression analysis, unadjusted odds ratios (ORs), 95% CIs, and P values of depression were estimated for selected variables. In multiple logistic regression analysis, all the selected variables were added simultaneously in the regression model to estimate adjusted ORs, 95% CIs, and P values. Statistical significance was determined by using P < .05 and 95% CIs.

Results

Patient Characteristics

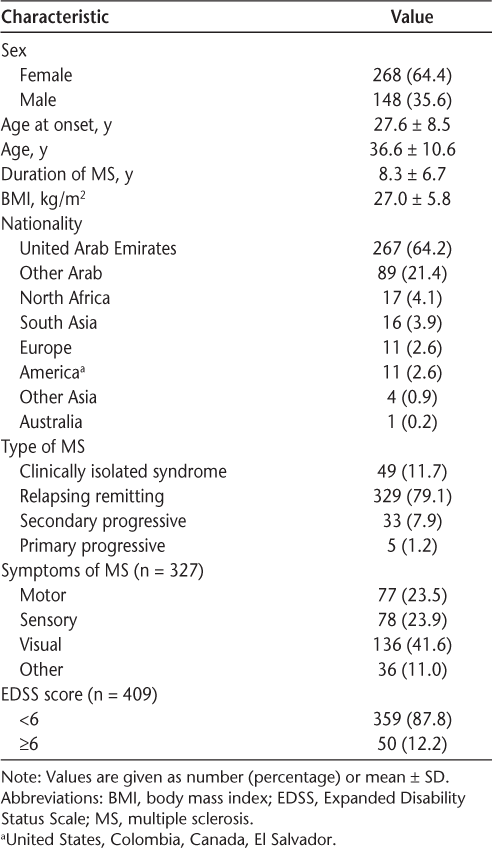

Of the 416 patients whose medical records were inspected, 268 (64.4%) were female and 148 (35.6%) were male, giving a female-to-male ratio of 1.81:1 (Table 1). A total of 267 patients (64.2%) were from the UAE, with the second largest number, 89 (21.4%), coming from other Arab countries. The mean ± SD age for the entire group was 36.6 ± 10.6 (range, 16–80) years, and the mean ± SD age at onset of MS was 27.6 ± 8.5 years.

Characteristics of the 416 study patients with MS

Consistent with other studies in the region,17,18 relapsing-remitting MS was the most common type of MS, with 329 cases (79.1%) (Table 1). Clinically isolated syndrome was the second most common presentation, with 49 cases (11.8%), followed by 33 cases of secondary progressive MS (7.9%) and five cases of primary progressive MS (1.2%). Information about presenting symptoms was recorded in 327 medical records, and the most common was visual (136 [41.6%]), followed by motor (77 [23.5%]) and sensory (78 [23.9%]). The mean ± SD duration since onset of MS symptoms was 8.3 ± 6.7 years.

The EDSS scores were categorized as less than 6 or 6 or greater due to interexaminer discrepancies and medical record inconsistencies.19 Of the 409 medical records in which EDSS score was recorded, 359 (87.8%) had an EDSS score less than 6.

Body mass index (BMI) was recorded for each patient as part of the medical record and was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared. The mean ± SD BMI in all patients was 27.0 ± 5.8 kg/m2, which falls under the World Health Organization definition of being overweight. A total of 234 of 410 patients (57%) had a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or greater. There was no statistically significant difference in depression or anxiety rates between patients with BMI of 25 kg/m2 or greater and those with BMI less than 25 kg/m2.

Depression and Anxiety

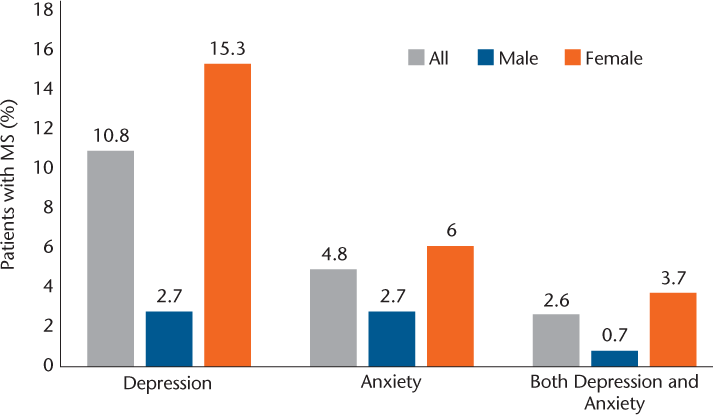

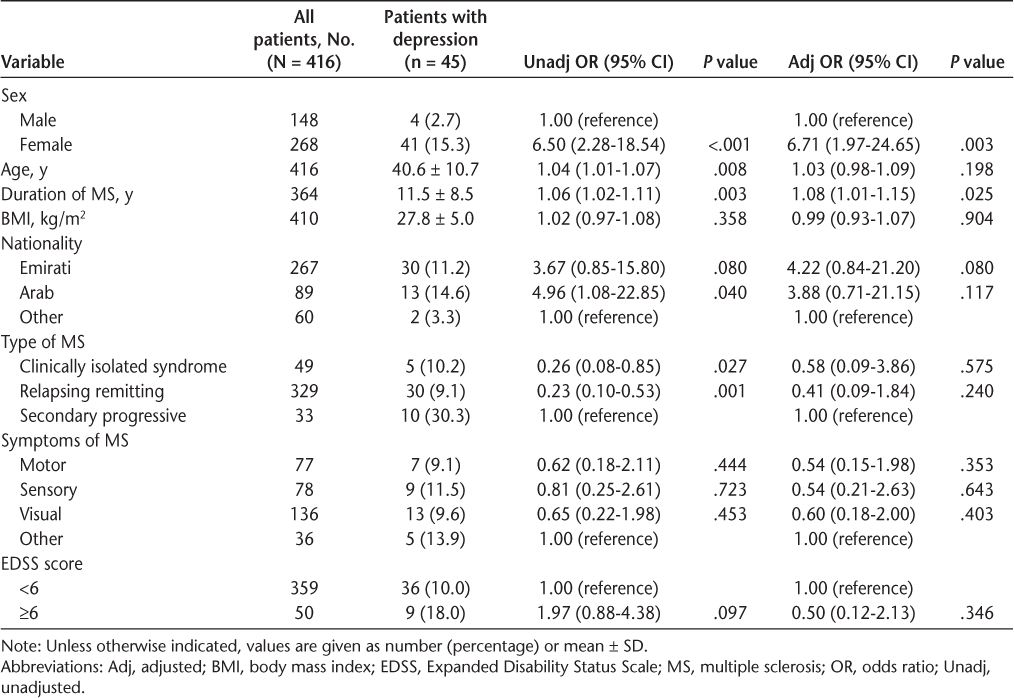

Of the total cohort, 45 (10.8%) had depression documented in their doctors' clinical notes or had depression coded as an ICD-9 number (Figure 1). Of the total female patients in the study, 15.3% had depression compared with only 2.7% of the males. The adjusted ORs and 95% CIs of depression by selected variables showed that there was a significant difference (P = .003) between female and male patients in reporting depression (Table 2). Of the total cohort, 20 (4.8%) had anxiety (6.0% of females and 2.7% of males). Among both female and male patients, 11 (2.6%) had both depression and anxiety (Figure 1).

Depression and anxiety in 416 people with multiple sclerosis (MS) followed up at four large government hospitals in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Unadjusted and adjusted ORs of depression by selected variables in patients with MS

Depression and Immunomodulatory Treatment

A well-known adverse effect of interferon beta (IFNβ) therapy is depression. Of the 45 people with documented depression, 25 (56%) were not taking interferon medication, 10 (22%) were taking interferons, and another 10 (22%) reported depression while taking interferons or any of the other immunomodulatory medications.

Of the total cohort of 416 patients, 231 (55.5%) were currently taking IFNβ or had taken it in the past. Of these 231 patients, 30 (12.9%) reported depression while taking IFNβ currently or previously and 10 (4.3%) reported depression regardless of medication. Of the 185 patients who had never taken IFNβ therapy, 15 (8.1%) reported depression.

Depression and MS Duration

Increase in MS duration was significantly associated with depression (P = .025) (Table 2). Among the 45 people with MS who were depressed, the likelihood of depression increased annually by 8%.

Treatment of Depression and Anxiety

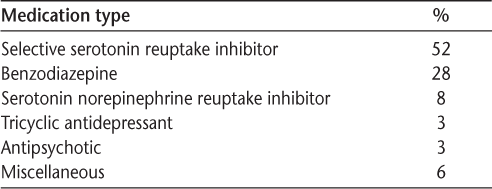

Of the 52 people with depression, anxiety, or both for whom we were able to find psychiatric medications listed, only three (5.7%) were not taking any antidepression or antianxiety medication. Most of these patients (94.3%) were prescribed medications for their disorder (Table 3).

Medication types prescribed for depression (n = 49)

Discussion

Rates of depression in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi have ranged from 22% in undergraduate students attending Al Ain University of Science and Technology20 to 13.9% in a random sampling of 1224 households in Abu Dhabi.21 Anxiety was determined to be 18.7% in the same cohort of 1224 households. There has been one study of depression in people with MS in Abu Dhabi, which found a 17% depression rate and a 20% anxiety rate in a cohort of 80 people with MS at Sheikh Khalifa Medical Center hospital, which showed that no variables (MS duration, age, sex, EDSS score) had any significant correlation with either depression or anxiety, and these rates were comparable with those of matched controls.15 The depression rate in people with MS in Abu Dhabi found in the present study (10.8%) was close to that found in the general population of Abu Dhabi (13.9%) and less than in the study by Alsaadi et al15 (17% in those with MS). Whether these findings indicate that those with MS in the UAE do not have an increased incidence of depression or whether the population as a whole, due to cultural and societal stigma factors, underreports depression cannot be determined from this study.

Factors that might explain the possibly underdetected rates of depression (and anxiety) include other confounding MS symptoms such as fatigue and cognitive impairment, the limited amount of time physicians are able to spend with their patients, and cultural aspects such as strong family support in the UAE. Culturally in the Middle East, admitting to depression is often considered a sign of weakness in males. Religious factors might also play a role: disclosing depression is often regarded as not accepting God's will and a sign of weak faith.

Interferon beta therapy, a commonly used immunomodulatory treatment, has been implicated to cause depression in individuals with MS22; however, there have also been reports indicating no association between IFNβ therapy and depression.23 In reviewing the medication history of the 45 people with depression in the present study, 25 patients (56%) were not taking IFNβ medication, 10 (22%) had depression, and the remaining 10 (22%) were depressed regardless of immunomodulatory therapy. Therefore, most (35 of 45 [78%]) of the depressed patients in the MS cohort had depression that was unassociated specifically with IFNβ medication, lending support to previous studies23 showing no association between depression and IFNβ medication. With some evidence indicating that an increasing number of patients are choosing to change from IFNβ to oral medications,24 it will be interesting to note whether the rates of depression in this population change.

Evidence is accumulating to support the role of diet and obesity in MS, with higher BMI considered a risk factor for the development of MS in the pediatric population.25 Increased BMI has also been shown to be associated with higher rates of depression in people with MS.26 A study of a random representative sample of 1224 adults in households in Abu Dhabi found that there was no statistically significant correlation between depression or anxiety and being obese or overweight.21 The present study of people with MS also did not show any relationship between BMI and anxiety or depression when adjusting for other factors despite more than half (57%) being classified as overweight or obese.

An encouraging finding from this study indicates that patients in whom depression and/or anxiety were recognized had a high chance of being prescribed an antidepressant; most (49 of 52 [94.2%]) were prescribed an antidepressant medication. We were unable to accurately determine how many patients were referred directly to psychiatry or were undergoing psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, or acceptance and commitment therapy because many patients receive this type of care in private clinics. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were the most commonly prescribed medications for depression (52%), followed by benzodiazepines (28%), and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (8%).

Limitations to this study include the limitations of retrospective medical record reviews27 as well as dependence on physicians reporting depression in their notes or ICD-9 coding for depression or anxiety. We were unable to assess individual depression scores or to correlate these to administered medication.

Future research should focus on better elucidating the link between depression and MS in the Middle East. This may also lead to a greater understanding of the pathophysiology of depression in MS with the potential to map the involved neuropathways. Owing to the stigma of mental health in the Middle East, it is difficult to know how many patients with MS also experience depression or anxiety. Understanding the link between depression and MS may be a step toward elucidating the increased prevalence of depression observed in patients with MS in the West.

There are a variety of ways that clinicians can screen for depression, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire, a validated screening tool. Another barrier to accurately assessing depressive symptoms may be family members or friends present at the visit. Providing patients with opportunities for confidential conversations should be a scheduled part of every visit, in which patients may discuss sensitive issues without the need to request that their family member(s) leave the room.

In conclusion, the depression rate in people with MS in Abu Dhabi in this study was close to that in the general population of Abu Dhabi and less than that in a previous study of people with MS in Abu Dhabi.15 There was a significant difference between female and male patients in reporting depression in this study, with more females reporting depression than males. The anxiety rate in this population was much lower than that in the general population. Cultural aspects such as strong family support systems and religious factors in this predominantly Muslim population warrant further investigation as explanatory factors.

PRACTICE POINTS

Depression rates in the MS population in the Arab world have rarely been reported despite people with MS generally having high rates of depression—possibly due to the cultural social stigma of mental illness in this society.

We conducted a retrospective medical record review for 416 people with MS in Abu Dhabi to determine the percentage diagnosed as having depression or anxiety and whether they were appropriately treated.

The depression rate in people with MS in Abu Dhabi (10.8%) was close to that in the Abu Dhabi general population. There was a significant difference (P = .003) between females and males in reporting depression, with more females reporting depression than males. Greater MS disease duration was also associated with a higher likelihood of being depressed (P = .025).

Most patients who reported depression or anxiety were prescribed medication. Whether the dose and type of medication were appropriate was not in the data collected, and neither were other psychological treatments (eg, psychotherapy).

Financial Disclosures:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105.

Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Allen J, et al. Depression and multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;46:628–632.

Murphy R, O'Donoghue S, Counihan T, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:697–708.

Feinstein A. The clinical neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:362.

Koch MW, Patten S, Berzins S, et al. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a long-term longitudinal study. Mult Scler. 2015;21:76–82.

Patten SB, Beck CA, Williams JV, Barbui C, Metz LM. Major depression in multiple sclerosis: a population-based perspective. Neurology. 2003;61:1524–1527.

Lobentanz IS, Asenbaum S, Vass K, et al. Factors influencing quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: disability, depressive mood, fatigue and sleep quality. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;110:6–13.

Fassbender K, Schmidt R, Mossner R, et al. Mood disorders and dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in multiple sclerosis: association with cerebral inflammation. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:66–72.

Raissi A, Bulloch AG, Fiest KM, McDonald K, Jette N, Patten SB. Exploration of undertreatment and patterns of treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:292–300.

Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, Beutler L, Gatto N, Langan MK. Identification of Beck Depression Inventory items related to multiple sclerosis. J Behav Med. 1997;20:407–414.

Marrie RA, Fisk JD, Tremlett H, et al. Differences in the burden of psychiatric comorbidity in MS vs the general population. Neurology. 2015;85:1972–1979.

McGuigan C, Hutchinson M. Unrecognised symptoms of depression in a community-based population with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2006;253:219–223.

Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:914–919.

Schiess N, Huether K, Fatafta T, et al. How global MS prevalence is changing: a retrospective chart review in the United Arab Emirates. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;9:73–79.

Alsaadi T, El Hammasi K, Shahrour TM, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among patients with multiple sclerosis attending the MS clinic at Sheikh Khalifa Medical City, UAE: Cross-sectional study. Mult Scler Int. 2015;2015:487159.

Al-Asmi A, Al-Rawahi S, Al-Moqbali ZS, et al. Magnitude and concurrence of anxiety and depression among attendees with multiple sclerosis at a tertiary care hospital in Oman. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:131.

Al-Hashel J, Besterman AD, Wolfson C. The prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the Middle East. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:129–137.

Inshasi J, Thakre M. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Int J Neurosci. 2011;121:393–398.

Meyer-Moock S, Feng YS, Maeurer M, Dippel FW, Kohlmann T. Systematic literature review and validity evaluation of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:58.

Abu Mellal A, Albluwe T, Al-Ashkar D. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and its socioeconomic determinants among university students in Al Ain, UAE. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6:309–312.

Moselhy HF, Ghubach R, El-Rufaie O, et al. The association of depression and anxiety with unhealthy lifestyle among United Arab Emirates adults. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2012;21:213–219.

Goeb JL, Even C, Nicolas G, Gohier B, Dubas F, Garre JB. Psychiatric side effects of interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21:186–193.

Kim S, Foley FW, Picone MA, Halper J, Zemon V. Depression levels and interferon treatment in people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2012;14:10–16.

Schiess N, Holroyd KB, Aziz F, Huether K, Szolics M, Alsaadi T. The rapidly changing landscape of multiple sclerosis immunomodulatory therapy: a retrospective chart review in the United Arab Emirates. J Mult Scler (Foster City). 2017;4:203.

Chitnis T, Graves J, Weinstock-Guttman B, et al. Distinct effects of obesity and puberty on risk and age at onset of pediatric MS. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3:897–907.

Cambil-Martin J, Galiano-Castillo N, Munoz-Hellin E, et al. Influence of body mass index on psychological and functional outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Neurosci. 2016;19:79–85.

Vassar M, Holzmann M. The retrospective chart review: important methodological considerations. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:12.