Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Improvement of Neuropsychological Function in Cognitively Impaired Multiple Sclerosis Patients Treated with Natalizumab

Author(s):

Treatment with natalizumab has been shown to reduce physical disability in people with multiple sclerosis (MS). However, its effect on neuropsychological dysfunction is not well understood. A single-center, open-label, retrospective study was conducted to evaluate the effect of natalizumab treatment on neuropsychological function in individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) who had a measurable neuropsychological deficit prior to natalizumab treatment. A total of 40 MS patients (mean age, 48.5 years; 77.5% female) were evaluated on a neuropsychological battery of nine tests designed for MS patients before and after 6 or more months of treatment with natalizumab. Posttreatment neuropsychological testing results were compared to baseline results. The mean baseline Neuropsychological Impairment Index was 0.49, which improved to 0.41 after treatment (P = .0002) as analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The mean Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II) score improved by 2.45 points (P = .001). The mean Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score improved by 0.30 (P = .02). A total of 52.5% of patients showed neuropsychological improvement, while 30.0% showed no change and 17.5% had worsening. Magnetic resonance imaging showed no changes. The specific prior disease-modifying therapy had no influence on the results for natalizumab effect. The results of this study show that natalizumab can stabilize or improve neuropsychological function in RRMS patients. The improvement was consistent with, but apparently independent of, improvement in depression and physical disability.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) that causes progressive neurologic disability by a combination of inflammation, demyelination, and axonal degeneration. Axonal degeneration and permanent disability may occur even at early stages of the disease.1–3 Several observational studies using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) to measure change in functioning over time have revealed much about the natural history of MS disability.4 5 Physical disability as measured by the EDSS has been shown to be reduced, compared to placebo, by several of the currently available disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for relapsing forms of MS. However, 50% to 65% of MS patients may develop neuropsychological impairment during the course of the disease.6–10 Because such impairment is a major cause of disability in MS patients, the importance of assessment of cognitive function in MS cannot be overestimated.6–8

Neuropsychological symptoms in MS commonly involve attention span, processing speed, multitasking, and working memory.7–11 Verbal fluency is typically spared, so that cognitive deficits may not be recognized in the absence of specific neuropsychological testing, which may not be performed until the deficits are advanced. Even in so-called benign MS, difficulty in the ability to process information may be great enough to prevent employment.12 Neuropsychological deficits may be independent of physical disability.6 Early cognitive impairment, however, may be associated with rapidly progressing physical disability as measured by the EDSS.11 13

Treatment with some DMTs appears to reduce neuropsychological impairment as compared with placebo. Weekly intramuscular (IM) interferon beta-1a (IFNβ-1a) has shown statistically significant neuropsychological benefit compared with placebo in a 2-year multicenter treatment trial using a comprehensive neuropsychological battery14 and a computerized battery.15 A 2-year trial with glatiramer acetate (GA) did not show any benefit over placebo with a comprehensive neuropsychological battery.16 Other studies of patients treated with DMTs have shown some benefit in neuropsychological function as measured by the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT), but comprehensive neuropsychological testing was not performed.17 18 In an early study involving IFNβ-1b, all but one neuropsychological function failed to show any improvement with treatment.19

Natalizumab has been shown to significantly reduce neurologic disability as measured by the EDSS in the AFFIRM and SENTINEL trials.20 21 Additionally, improvements in PASAT scores in the AFFIRM and SENTINEL trials suggested a neuropsychological benefit compared with placebo.18 To date, results from a comprehensive neuropsychological battery in patients assessed before and after treatment with natalizumab have not been published.

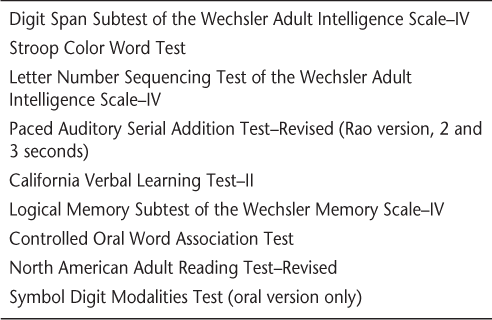

Because cognitive dysfunction is a significant cause of disability in MS patients, members of our MS center have long had a special interest in it.9 22 When appropriate, we perform not only yearly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies to measure adequacy of a DMT but also a neuropsychological battery (Table 1) that is similar to the Minimal Assessment of Cognitive Functions in Multiple Sclerosis (MACFIMS).23 Unlike the MACFIMS, our battery is designed to avoid the confounding issue of motor movements in the measurement of cognitive abilities. Although similar to the MACFIMS battery in scope and length, the battery does not include tasks requiring motor output and thus does not assess visual memory. Tests included in the battery reflect the most common neuropsychological deficits in MS: processing speed, working memory, word retrieval, and executive functions. Baseline and follow-up testing are performed, allowing the efficacy of a DMT in preventing disability to be measured not only by the EDSS but also by neuropsychological status.

Cognitive assessment protocol for multiple sclerosis

The current study was conducted to evaluate the effect of natalizumab treatment on neuropsychological function in individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) who had a measurable neuropsychological deficit prior to the initiation of natalizumab.

Patients and Methods

This single-center, open-label, retrospective study involved 40 consecutive natalizumab-treated MS patients with a measurable neuropsychological deficit prior to natalizumab treatment. Male and female patients were eligible to participate if they had RRMS, were aged 18 to 60 years, had been administered a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation prior to receiving natalizumab, and had received at least six treatments of natalizumab, with repeat neuropsychological testing. Posttreatment test results were compared with pretreatment results. None of the patients had significant concomitant illness, medication changes, or any other factor that might cause neuropsychological dysfunction. The study was approved by the BioMed Institutional Review Board. Because the analyses were retrospective and related to data used for routine treatment, no patient consent forms were necessary.

Each subtest of the neuropsychological evaluation specific for MS (Table 1) was rated as normal or abnormal, defined as one or more standard deviations (SD) from the norm. Each of the nine subtests was assigned a value of zero if normal or 0.11 if abnormal.15 Therefore, a patient with a score of zero showed no cognitive dysfunction, since no test scores were at or more than one SD from the norm. A score of 0.22 indicated mild cognitive dysfunction, a score of 0.44 indicated moderate cognitive dysfunction, and a score of above 0.66 to 0.99 indicated severe cognitive dysfunction. Those values were summed to create a total Neuropsychological Impairment Index, with lower scores indicating impairment in fewer domains. If the impairment index score was 0.22 or higher, the patient was considered neuropsychologically “impaired” and qualified for enrollment in the study.

Our primary analysis compared the pre–natalizumab treatment Neuropsychological Impairment Index score to the posttreatment score. We also assessed changes in the Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II) score, EDSS score, and MRI data, as well as prior DMT use.

Treatment and Procedures

Natalizumab, 300 mg, was given intravenously over 1 hour every 4 weeks, followed by a 1-hour observation period. Infusions were administered at the MS Center of Northeastern New York by an infusion nurse belonging to the International Organization of MS Nurse Specialists (IOMSNS). There were no changes in concomitant medications or illnesses that would affect neuropsychological testing results during the observation and testing periods.

Statistical Analyses

Comparison of baseline with posttreatment data was performed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test to calculate P values. Exploratory analyses for possible interactions between neuropsychological changes and EDSS score or depression were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) adjusted for age and baseline values.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

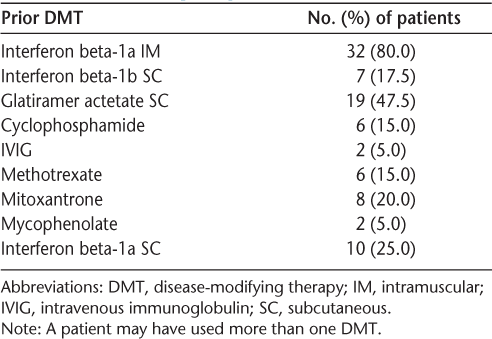

Of the 40 patients, there were 31 females (77.5%) and 9 males (22.5%). The mean (SD) age was 48.5 (6.87) years. The mean number of natalizumab infusions was 11.4. Prior DMT use included most FDA-approved medications and some immunosuppressants (Table 2). The mean (SD) EDSS score at baseline was 4.59 (1.24). The mean (SD) BDI-II score at baseline was 13.3 (10.5). The mean (SD) neuropsychological impairment rating at baseline was 0.49 (0.21). Standard cranial MRI with and without contrast enhancement was performed on a 1.5-T magnet before initial treatment with natalizumab.

Summary of prior individual DMT use

Treatment Effects

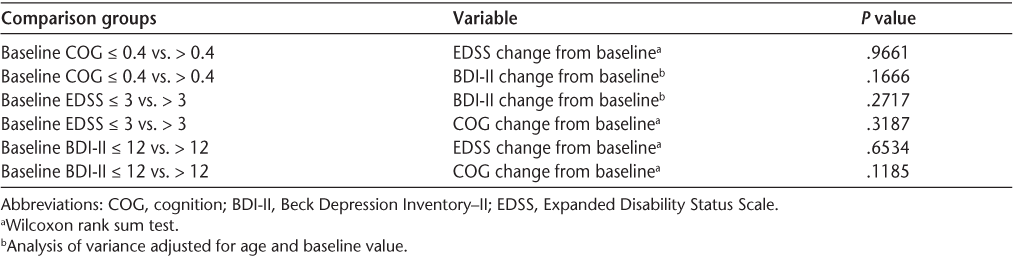

Comprehensive neuropsychological performance improved from a mean Neuropsychological Impairment Index score of 0.49 at baseline to a mean score of 0.41 at the time of retesting (P = .0002). Depression ratings on the BDI-II improved from a mean score of 13.30 to a mean score of 10.85 (P = .001). The mean EDSS score improved from 4.59 to 4.29 (P = .02). A total of 52.5% of patients showed neuropsychological improvement, while 30.0% showed no change and 17.5% had worsening. Although all three functional measures improved, there was greater improvement in cognition than in depression or disability rating. Analysis of variance adjusted for age and baseline values did not show any statistically significant correlations between cognition and depression or EDSS score with specified baseline conditions (Table 3).

Analysis of variance

Safety

There were no adverse events associated with natalizumab in any of the 40 patients during the treatment period. There were no serious infusion reactions, laboratory abnormalities, or cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

Discussion

This is the first study that we know of to demonstrate an improvement in cognition as assessed by a comprehensive neuropsychological battery with natalizumab treatment for patients with RRMS within a single year. Previous studies using comprehensive neuropsychological batteries have not consistently demonstrated improvement following treatment with other DMTs in MS.19 24 The ability to detect neuropsychological changes in such a small cohort of patients, in contrast to the failure to do so in much larger phase 4 clinical trials, points to either a stronger effect of natalizumab on cognition or the superior sensitivity of the test battery employed here. Moreover, individuals in this study showed some degree of cognitive impairment at baseline, which may not have been the case in other studies. Thus, our patients may have been better positioned to show measurable change.

Neuropsychological symptoms may be subtle, may be confused with depression or anxiety, or may be comorbid with mood disturbance. As shown by careful testing in other studies, cognitive impairment may be disabling even if the EDSS score is in the traditionally “benign” category.12 Just as changes in physical disability may prompt a change in DMT, a decline in neuropsychological function may warrant a change in treatment in order to limit progression.

A comprehensive neuropsychological battery is needed to assess cognitive function in people with MS. The PASAT-3″ may be a useful screening test, but other evaluations are needed to achieve an understanding of overall neuropsychological function. The neuropsychological battery used in this study (Table 1) was adapted from the MACFIMS to avoid tasks requiring motor output. To ensure that not just one or two of the tests were significantly affecting the total Neuropsychological Impairment Index, an analysis of individual tests using the paired t test or Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed. The results indicated that there was no single individual test that influenced the impairment index as a whole.

This limited, retrospective study suggests that natalizumab may stabilize or even improve neuropsychological status in some RRMS patients with pre-existing neuropsychological deficits, including those who have experienced progression of disease with prior trials of DMTs (Table 2). Multivariate analyses indicated that improvement in cognitive impairment was independent of improvement in depression or physical impairment. Prospective studies are needed to confirm this observation.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that natalizumab therapy can stabilize or improve neuropsychological performance in a substantial proportion of MS patients. This finding is clinically relevant to a population that is expected to have progressive decline in neuropsychological function over time. Changes in neuropsychological function can be detected even in the absence of disease progression as measured by the EDSS. These results support the effectiveness of natalizumab therapy in the treatment of both physical disease activity and cognitive impairment in patients with RRMS. Testing for neuropsychological performance is an important component of overall evaluation of the physical, cognitive, and mental health of MS patients. A prospective multicenter trial is needed to confirm the preliminary results of this study. Because cognitive dysfunction is a major cause of disability in MS patients, the results of comprehensive neuropsychological testing should be a primary or at least a secondary outcome measure in future multicenter trials of DMTs for MS.

PracticePoints

Neuropsychological dysfunction is the most common cause of disability in individuals with MS, affecting up to 65% of patients.

Despite its high prevalence in MS, neuropsychological dysfunction is often overlooked, and recognition of impairments requires vigilance by patients and physicians.

Natalizumab can have a stabilizing effect on neuropsychological dysfunction in MS patients. Some patients may experience a measurable improvement in cognitive function, independent of mood or physical function, after 6 months of treatment with natalizumab.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Vineetha Kamath for her excellent technical assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, Rudick R, Mork S, Bo L. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338: 278–285.

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008; 372: 1502–1517.

Lucchinetti C, Bruck W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann Neurol. 2000; 47: 707–717.

Roxburgh RH, Seaman SR, Masterman T, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score: using disability and disease duration to rate disease severity. Neurology. 2005; 64: 1144–1151.

Brex PA, Miszkiel KA, O'Riordan JI, et al. Assessing the risk of early multiple sclerosis in patients with clinically isolated syndromes: the role of a follow up MRI. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001; 70: 390–393.

Amato MP, Ponziani G, Pracucci G, Bracco L, Siracusa G, Amaducci L. Cognitive impairment in early-onset multiple sclerosis: pattern, predictors, and impact on everyday life in a 4-year follow-up. Arch Neurol. 1995; 52: 168–172.

Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns and prediction. Neurology. 1991; 41: 685–691.

Rao SM, Leo GJ, Ellington L, Nauertz T, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. II. Impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology. 1991; 41: 692–696.

Peyser JM, Edwards KR, Poser CM, Filskov SB. Cognitive function in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1980; 37: 577–579.

Patti F. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2009; 15: 2–8.

Deloire MS, Salort E, Bonnet M, et al. Cognitive impairment as marker of diffuse brain abnormalities in early relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005; 76: 519–526.

Rovaris M, Riccitelli G, Judica E, et al. Cognitive impairment and structural brain damage in benign multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2008; 71: 1521–1526.

Lynch SG, Parmenter BA, Denney DR. The association between cognitive impairment and physical disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005; 11: 469–476.

Fischer JS, Priore RL, Jacobs LD, .; Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group. Neuropsychological effects of interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2000; 48: 885–892.

Wilken JA, Kane R, Sullivan CL, et al. The utility of computerized neuropsychological assessment of cognitive dysfunction in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2003; 9: 119–127.

Weinstein A, Schwid SR, Schiffer RB, McDermott MP, Giang DW, Goodman AD. Neuropsychologic status in multiple sclerosis after treatment with glatiramer. Arch Neurol. 1999; 56: 319–324.

PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and Disability by Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneously in Multiple Sclerosis) Study Group. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998; 352: 1498–1504.

Rudick RA, Polman CH, Cohen JA, et al. Assessing disability progression with the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite. Mult Scler. 2009; 15: 984–997.

Pliskin NH, Hamer DP, Goldstein DS, et al. Improved delayed visual reproduction test performance in multiple sclerosis patients receiving interferon beta-1b. Mult Scler. 1996; 47: 1463–1468.

Polman CH, O'Connor PW, Havrdova E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354: 899–910.

Rudick RA, Stuart WH, Calabresi PA, et al. Natalizumab plus interferon beta-1a for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354: 911–923.

Edwards K, Goodman W, Wilken J, et al. Computerized testing to screen for cognitive impairments in MS. Mult Scler. 2009; 15:S230.

Benedict RH, Fischer JS, Archibald CJ, et al. Minimal neuropsychological assessment of MS patients: a consensus approach. Clin Neuropsychol. 2002; 16: 381–397.

Galetta SL, Markowitz C, Lee AG. Immunomodulatory agents for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162: 2161–2169.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Edwards has received financial compensation from Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Biogen Idec for serving on their scientific advisory boards, as well as from Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, Acorda, and EMD Serono for serving as a speaker. He has received financial support for research activities from Biogen Idec, Novartis, Actelion, Acorda, Genzyme, EMD Serono, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Sanofi-Aventis. Drs. Goodman and Ma have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by funding from Biogen Idec.