Publication

Research Article

International Journal of MS Care

Evaluation of a Novel Preference Assessment Tool for Patients with Multiple Sclerosis

Author(s):

Abstract

Background:

We developed a preference assessment tool to help assess patient goals, values, and preferences for multiple sclerosis (MS) management. All preference items in the tool were generated by people with MS. The aim of this study was to evaluate this tool in a national sample of people with MS.

Methods:

English-speaking patients with MS aged 21 to 75 years with access to the internet were recruited. Participants completed the preference tool online, which included separate modules assessing three core preference areas: treatment goals, preferences for attributes of disease-modifying therapies, and factors influencing a change in treatment. The tool generated a summary of participants' treatment goals and preferences. Immediately after viewing the summary, participants were asked to evaluate the tool. Rankings of preference domains were compared with rankings obtained in another study.

Results:

In 135 people with MS who completed the tool and evaluation, the highest ranked goal was brain health (memory, thinking, brain), followed by disability concerns (walking, strength, vision). Rankings were highly similar to those in the referent study. Nearly all participants reported that the tool helped them understand their goals and priorities regarding MS and that the summary appropriately reflected what is important to them. Most participants (87%) wanted to discuss their treatment goals and priorities with their clinician.

Conclusions:

This preference assessment tool successfully captured patients' goals, values, and preferences for MS treatment and could potentially be used to help patients communicate their preferences to their clinician.

Understanding patient values is crucial to shared decision making (SDM).1 Shared decision making is essential for high-stakes decisions about multiple sclerosis (MS) when choosing the best treatment depends on how a patient values the risks and benefits of their options.2 The essential elements of SDM include informing patients when they face a decision, ensuring that patients understand their condition and their options, eliciting patients' values and preferences, and helping them apply their values to the decision.3 However, eliciting patient values is challenging and time-consuming, and there is no consensus on how it should be performed.4 Asking patients what they value is often ineffective because patients may not have preformed ideas about what is most important to them and may need help applying deeply held values to clinical decisions.5,6 Values clarification methods aim to help patients determine what matters to them,4 but they typically rely on preference items selected by the developer or physicians,7 which may not be relevant to patients.8

We developed a novel preference assessment tool to help patients with MS clarify, summarize, and share their treatment goals and preferences with their clinician. The utility of the tool, which is designed around preference attributes previously identified by patients with MS, depends critically on the representativeness of its preference items. This cross-sectional validation study seeks to evaluate the accuracy, completeness, and representativeness of the preference attributes included in the tool; the preference summary it generates; whether it helps clarify patient preferences; and patients' interest in sharing their preferences with clinicians, and to compare its preference rankings with those of another method.

In this study, we use the term preference to describe what patients want from their health care,9 encompassing preferences for the attributes of treatments (which some studies refer to as values) and treatment goals.

Methods

Overview

This study is part of a larger study to develop a tool to assess patient goals and preferences for MS treatments (the MS Decisions Study). This study was approved by the New England Independent Review Board (Needham, MA).

Setting and Participants

Participants were limited to nonpregnant English-speaking patients with internet access aged 21 to 75 years who self-identified as having MS. All the participants were identified through patient and clinician advisers with access to MS networks, purposefully selecting patients from different regions with different socioeconomic backgrounds and disease characteristics to obtain the most information (eg, a purposive sampling design). Participants were referred to the panel through MS support groups, health blogs, educational events, and private Facebook groups.

Data Collection

Participants were e-mailed invitations in October and November 2016 that included a Web link to a secure website that directed the participant through the informed consent document, baseline sociodemographic and clinical questions, the preference tool, and evaluation questions. On completion, participants received a modest incentive payment.

Preference Tool

The tool guides patients through three preference modules: identifying treatment goals, identifying preferences for disease-modifying therapy (DMT) attributes (or features), and identifying factors driving a change in treatment. Assessing patients' treatment goals is consistent with clinical practice guidelines,10 considering how patients value the specific features of DMTs is essential to SDM and values clarification, and identifying patients' interest in changing how they manage their MS identifies whether patients face a decision. All three items map to a validated conceptual model describing how people make value-laden decisions.11

In each module, participants identified the most important broad preference domains (choosing five from a list of seven to ten domains) and then rank ordered them. For example, in the treatment goals module, domains included “avoiding flare-ups or progression” and “having a caring and knowledgeable medical team.” Next, participants rated the importance of specific preference items conceptually associated with the domains using a 6-point Likert scale (”not affected or NA,” “not so important,” “somewhat important,” “important,” “very important,” and “extremely important”). If more than five specific items were identified as “extremely important,” the user was asked to select the five most important items. Only participants who reported having taken or thought about taking a DMT were shown the DMT module.

The preference domains and specific items in each domain were derived by patients with MS using previously published methods.12 In brief, we conducted nominal group technique meetings with patients with MS to elicit and prioritize preference items. We combined findings across nominal group technique groups to create a composite list of preference items. Card sorting was used by a larger sample to organize preference items into meaningful clusters (domains) and create cluster labels. Multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis were used to derive a visual representation, or cognitive map, of the data and to identify conceptual domains based on how frequently preference items were sorted into the same category.

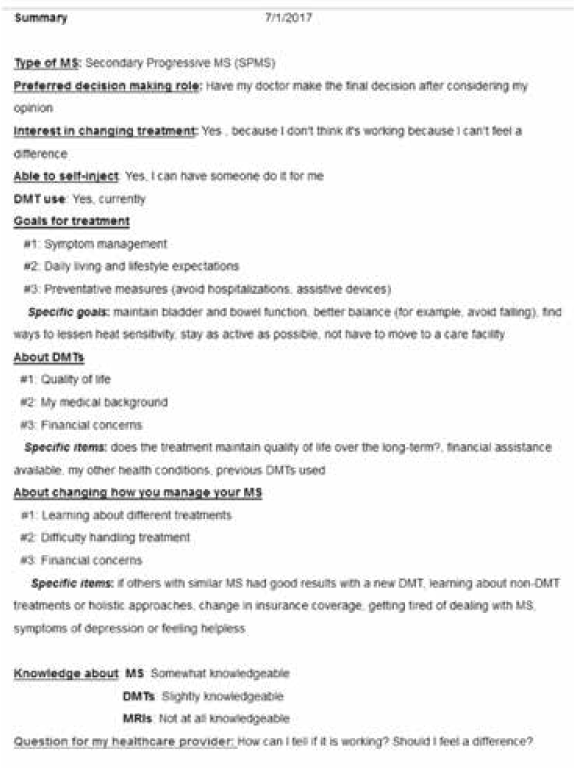

The tool also assesses other SDM elements (preferred decision-making role,13 stage of decision making,14 and self-rated knowledge about MS) and clinical information (type of MS, DMT use, ability to self-inject, and questions to ask their clinician). The tool generates a preference summary (Figure 1) that can be printed or e-mailed to facilitate sharing with their clinician. The tool was created using Qualtrics software (Seattle, WA).

Sample summary page

Evaluation of Preference Tool

Participants were asked to evaluate the tool online immediately after viewing their personalized summary: “How well does this summary reflect what matters to you when it comes to treating your MS?”, “To what extent were your personal goals and priorities represented in these questions?”, “Did the process of completing this survey help you understand your goals and priorities regarding MS?”, “Do you think it would be helpful if your health care provider knew your treatment goals and priorities?”, and “Would you like your MS health care provider to discuss your treatment goals and priorities with you?” Survey responses used a 5-point Likert scale (eg, “very few were represented,” “some were represented,” “most were represented,” “nearly all were represented,” or “all were represented”; “not at all helpful” to “extremely helpful”; and “poorly” to “extremely well”).

Data Analysis

To identify the domains most often selected by participants, we computed a simple weighted average (ie, 5 points for the first, 1 point for the fifth, 0 points for others). Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). We used the Spearman coefficient to assess the correlation between the rankings of domains observed in previous analyses12 and the rankings observed in these data. We also used a regression model to estimate the slope and its 95% CI between these two rankings and generated Bland-Altman plots. We considered a correlation of 0.7 or greater to be an excellent correlation and the 95% CI of the slope including 1 to indicate excellent agreement between the two rankings.

Results

Of the 209 panel members invited to participate, 135 (64.6%) consented and completed the tool and evaluation; 68 (32.5%) did not respond to the invitation; and 6 (2.9%) did not give informed consent. Of those who completed the tool, 129 (95.6%) completed the DMT module (6 participants who had never considered taking a DMT were not presented this module). All the activities took an average of 30.9 minutes to complete, which included screening questions, informed consent, baseline questions, the preference tool itself, and an evaluation of the preference tool. One-third of participants (31%) completed all the items within 25 minutes.

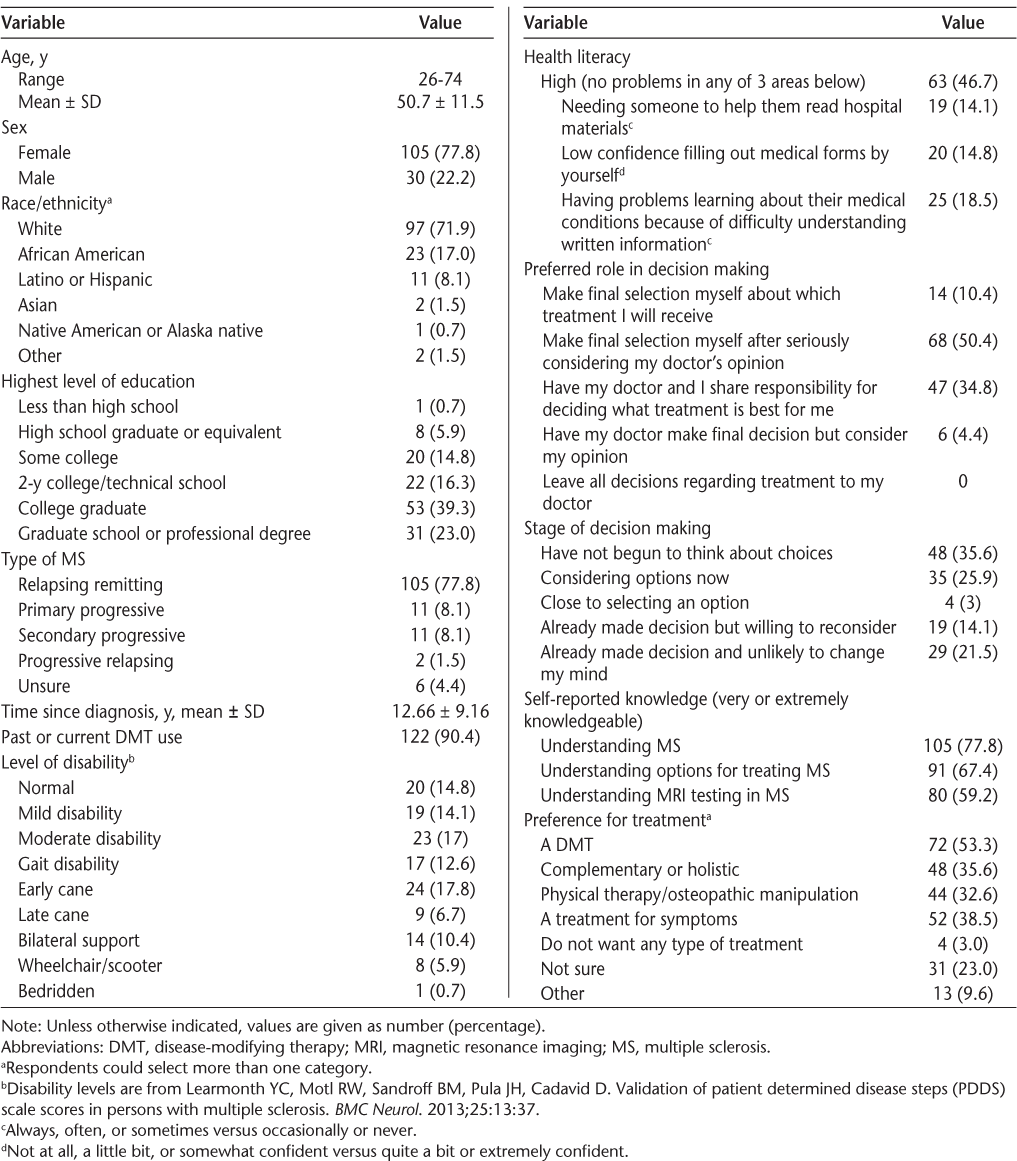

The patient sample (Table 1) seems to be representative of patients with prevalent MS, being similar to a representative study's sample (which was 72% female).15 Nearly all the participants preferred an autonomous or SDM role.

Participant demographic features and decision process measures (n = 135)

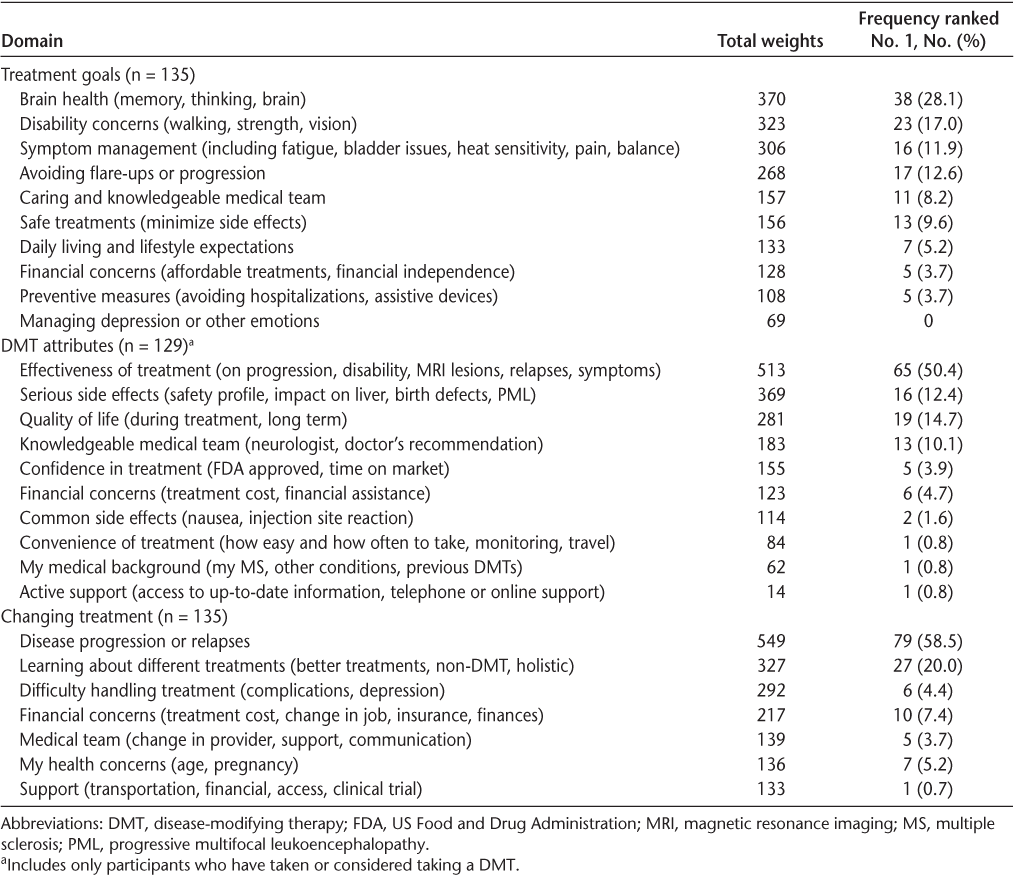

All the preference domains were chosen as a top concern by at least one participant, although some domains were more often highly ranked than others. No two patients reported identical preferences. The highest-ranked treatment goal domain was brain health, followed by disability concerns (Table 2). The highest-ranked domain for DMT features was effectiveness of treatment, followed by serious side effects. The highest-ranked domain for changing treatment was disease progression or relapses, followed by learning about different treatments. With respect to the specific preference items, the most highly rated goal was avoid or slow progression of MS, followed by have a doctor who is knowledgeable and compassionate about MS (Table S1, which is published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org). For DMT features, the most highly rated item was effectiveness in preventing brain volume change, followed by effectiveness in preventing new or enlarging MRI lesions. For changing treatment, the most important item was losing physical or mental function, followed by physical activity becomes limited.

Domains in the three core preference areas, ranked among the five most important to patients, by decreasing order of frequency

The rank ordering of domains observed in the present study was highly similar to that obtained in the referent (gold standard) study12 (Table S2 and Figure S1), for both treatment goals and DMT features.

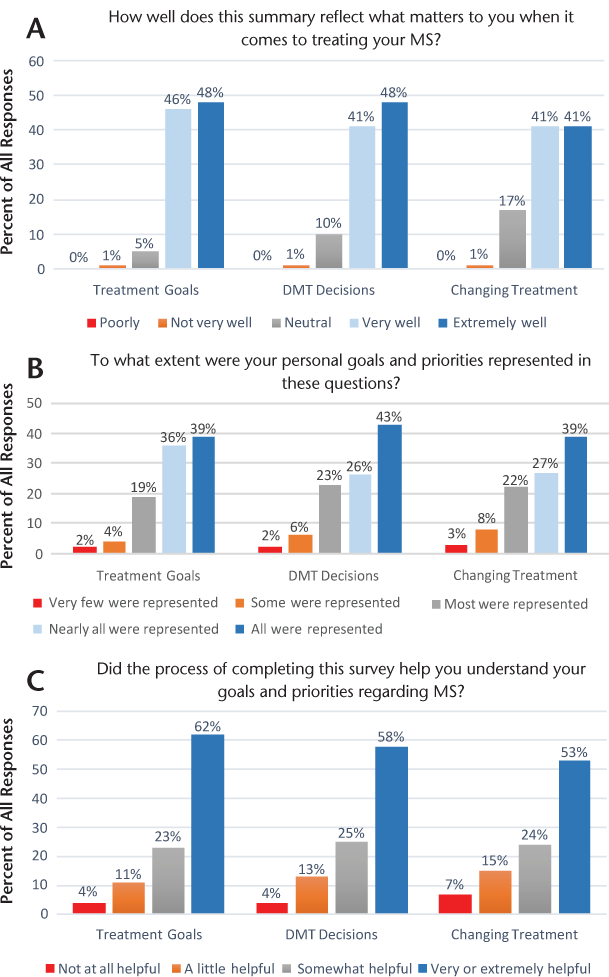

After viewing the summary of their prioritized preferences, nearly all the participants reported that the preference summary reflected what matters to them when it comes to treating their MS and represented their treatment goals “very well' or “extremely well” (Figure 2A). Nearly all the participants reported that most, nearly all, or all of their own goals and preferences were represented in the tool (Figure 2B). Most participants reported that the process of completing the tool was very or extremely helpful in understanding their goals and priorities regarding MS (Figure 2C).

Graphs showing how the preference assessment tool reflects what matters to patients (A), represents patients' goals and preferences (B), and helps patients understand their goals and priorities (C) regarding multiple sclerosis (MS) treatment

Most participants (87%) wanted to discuss their treatment goals and priorities with their MS clinician, although many (37%) reported not routinely sharing their goals and priorities with their clinician. Most participants (75%) reported that it would be very helpful or extremely helpful if their MS clinician were aware of their treatment goals and priorities and 19% that it would be somewhat helpful; none felt uncomfortable discussing this with their provider.

Discussion

The MS preference assessment tool successfully captured and summarized most patients' goals and preference. This finding was unexpected given the complexity and uncertainties of MS and its treatment and likely reflects the robustness of the methods used to identify the preference attributes in the tool. The finding that no two patients had identical preference profiles demonstrates the complexity of making inferences about what matters to a patient with MS and the importance of eliciting preferences directly from the patient. Other studies demonstrated differences between physicians' assumptions about what their patients preferred and patient-stated preferences.16–18 That the tool helped patients understand their own treatment goals and preferences and generated an accurate summary that could be shared with clinicians suggests that this simple approach to preference elicitation may prove helpful in promoting SDM in clinical settings, although further testing is needed.

The present finding that preserving brain health was more important than either disability concerns or avoiding relapses is consistent with other studies. One study19 concluded that mental disability was more worrisome to patients with MS than physical disability (whereas the opposite was true for clinicians) and that patients were more concerned with broad domains such as mental health and vitality than physical functioning or physical role limitations. Another study found that patient preferences for DMT attributes focused on symptoms and prevention of progression but not on relapse prevention.20

When treatments potentially influence many outcomes, decision makers typically give higher priority to outcomes that are more salient and concrete than to those that are “fuzzier” and more difficult to evaluate.21,22 The risks of DMTs are typically described concretely (eg, liver failure), whereas their benefits are often described using fuzzier terms, such as delaying progression. This difference in terminology could bias patients with MS to place more weight on risks than benefits. Awareness of a patient's specific preferences could help reframe benefits and risks using comparable levels of concreteness, thereby minimizing this bias.

Some preference items in the tool are difficult to interpret because they do not map to outcomes reported in clinical trials (eg, brain health), or they seem conflicted or misinformed (eg, “Will I feel better while on treatment?”). Although those preference items may not lend themselves to guiding treatment decisions, they may provide opportunities for clinicians to validate the patient's attempt to express their preferences (eg, “I hear you”), ask questions (eg, “tell me more”), and show support for their perspective (eg, “I understand why you might feel this is important”). This, in turn, can build partnership, generate ideas that correct misconceptions,23 and help patients integrate their understanding and feelings24 into preferences for treatment that can be articulated and enacted.25

Many study participants who wanted to discuss their treatment preferences with their clinician did not routinely do so. Physicians can encourage or obstruct patient involvement.26 Patients are more active when interacting with physicians who engage in partnership-building and supportive talk that legitimizes the patient's perspective and creates expectations and opportunities for the patient to discuss their needs and concerns.27 Recognizing that physicians only occasionally use partnering or supportive communication,27 offering patients a tool that “invites” them to share their preferences could demonstrate the clinician's interest in what matters to the patient and create an expectation to discuss their preferences.

This study has several limitations. We relied on self-report, which may have led to a tendency for more favorable responses. We did not confirm a diagnosis of MS. However, our referral sources made incorrect diagnosis unlikely. We focused on preference areas most relevant to SDM and values clarification and may have missed other areas. The tool requires internet access, which restricts access for some but facilitates access for many others. Patients highly endorsed most specific preference items, rendering differences in ratings less meaningful. However, the ratings themselves are less important than the process of rating values, which requires engagement.28 The validation studies used the hierarchy of preferences identified in the previous study as the gold standard because it is the only comparison set available at this time. There are challenges to identifying an ideal gold standard for assessing patient preferences. This study represents the first step in the evaluation process; the impact of the tool on communication, SDM, length of the visit, and other clinical outcomes has not yet been determined.

Helping patients communicate their preferences facilitates SDM, which can help clinicians tailor conversations to the outcomes that matter to patients and can also trigger clinicians to provide more information and support.29 But there are significant challenges involved that hinder the adoption of SDM.30 For example, clinicians typically do not engage in SDM when they believe that their patients cannot assume an active role, and patients do not assume an active role when they do not understand why or how their preferences factor into a decision. Adoption of SDM is also limited by perceptions that it will take too much time. Helping patients prioritize what matters to them before the clinical encounter should improve clinical efficiency.31 Making clinicians aware of a patient's preferred involvement in care should help clinicians tailor communication to the patient's desired level of participation, which can improve their understanding of information.32

The MS preference assessment tool evaluated herein presents a novel approach to help patients clarify, summarize, and share their values with their clinician. The present encouraging findings were used to refine the tool (available at https://tinyurl.com/WhatMattersMS) and develop a preference-centered decision aid. Future studies will further validate the tool by exploring its feasibility and effectiveness at point of care in a randomized controlled trial.

PRACTICE POINTS

Shared decision making (SDM) is increasingly endorsed and incentivized in health care.

Assessing a patient's goals, preferences, and values is a crucial element of SDM but is challenging to implement in clinical practice.

We developed a practical online tool that helps patients with MS clarify and summarize their treatment goals and preferences so that they can be shared more easily with their clinicians.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Col has received consulting fees and research support from Biogen, consulting fees from Janssen Scientific Affairs (for work unrelated to MS), and research support from Pfizer (for work unrelated to MS). Dr. Solomon has received consulting fees from Biogen, EMD Serono, and Teva Pharmaceuticals and has served as a professional consultant to Five Islands Consulting LLC. Dr. lonete has received consulting fees and research support from Genzyme and Biogen. Dr. Berrios Morales has participated on an advisory board for Genzyme. Dr. Jones has received consultant fees from Biogen, Novartis, and Genzyme and research support from Biogen. Dr. Phillips is an employee of Biogen. Drs. Kutz, Ngo, and Pbert and Mss. Springmann, Tierman, Hopson, and Griffin have served as professional consultants to Five Islands Consulting LLC.

References

Say RE, Thomson R. The importance of patient preferences in treatment decisions: challenges for doctors. BMJ. 2003;327:542–545.

Col NF. Patient health communication to improve shared decision making. In: Fischhoff B, Brewer NT, Downs JS, eds. Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence-Based User's Guide. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Risk Communication Advisory Committee and consultants. 2011

Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;60:301–312.

Witteman HO, Scherer LD, Gavaruzzi T, et al. Design features of explicit values clarification methods: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2016;36:453–471.

Peters E, Dieckmann N, Dixon A, Hibbard JH, Mertz CK. Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2007; 64:169–190.

Hibbard JH, Slovic P, Jewett JJ. Informing consumer decisions in health care: implications from decision-making research. Milbank Q. 1997;75:395–414.

Hollin IL, Young C, Hanson C, Bridges JF, Peay H. Developing a patient-centered benefit-risk survey: a community-engaged process. Value Health. 2016;19:751–757.

Shalowitz Dl, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:493–497.

Street RL Jr, Elwyn G, Epstein RM. Patient preferences and healthcare outcomes: an ecological perspective. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12:167–180.

Goodin DS, Frohman EM, Garmany GP, Halper J, Likosky WH, Lublin FD. Disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2002;58:169–178.

Nelson KA. Consumer decision making and image theory: understanding value-laden decisions. Consumer Psychol. 2004;14:28–40.

Col NF, Solomon AJ, Springmann V, et al. Whose preferences matter? a patient-centered approach for eliciting treatment goals. Med Decis Making. 2018;38:44–55.

Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The control preferences scale. Can Nurs Res. 1997;29:21–43.

O'Connor AM. User manual-stage of decision making. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2000. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Stage_Decision_Making.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2017.

Lublin FD, Cofield SS, Cutter GR, et al. Randomized study combining interferon and glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:327–340.

Tintore M, Alexander M, Costello K, et al. The state of multiple sclerosis: current insight into the patient/health care provider relationship, treatment challenges, and satisfaction. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:33–45.

Lee CN, Hultman CS, Sepucha K. Do patients and providers agree about the most important facts and goals for breast reconstruction decisions? Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:563–566.

Devereaux PJ, Anderson DR, Gardner MJ, et al. Differences between perspectives of physicians and patients on anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: observational study. BMJ. 2001;323:1218–1222.

Rothwell PM, McDowell Z, Wong CK, Dorman PJ. Doctors and patients don't agree: cross sectional study of patients' and doctors' perceptions and assessments of disability in multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 1997;314:1580–1583.

Wilson LS, Loucks A, Gipson G, et al. Patient preferences for attributes of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies: development and results of a ratings-based conjoint analysis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:74–82.

Hsee C. The evaluability hypothesis: an explanation for preference reversals between joint and separate evaluations of alternatives. Organizational Behav Hum Decis Processes. 1996;67:247–257.

Mellers BA, Richards V, Birnbaum M. Distributional theories of impression formation. Organizational Behav Human Decision Processes. 1992;51:313–343.

Meegan SP, Berg CA. Contexts, functions, forms, and processes of collaborative everyday problem solving in older adulthood. Int J Behav Dev. 2002;26:6–15.

Johnson EJ, Steffel M, Goldstein DG. Making better decisions: from measuring to constructing preferences. Health Psychol. 2005;24(suppl 4):17S–22S.

Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. Shared mind: communication, decision-making, and autonomy in serious illness. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:454–461.

Makoul G. Perpetuating passivity: reliance and reciprocal determinism in physician-patient interaction. Health Commun. 1998;3:233–259.

Street RL Jr, Gordon HS, Ward MM, Krupat E, Kravitz RL. Patient participation in medical consultations: why some patients are more involved than others. Med Care. 2005;43:960–969.

Pieterse AH, de Vries M, Kunneman M, Stiggelbout AM, Feldman-Stewart D. Theory-informed design of values clarification methods: a cognitive psychological perspective on patient health-related decision making. Soc Sci Med. 2013;77:156–163.

Street RL Jr. Information-giving in medical consultations: the influence of patients' communicative styles and personal characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:541–548.

Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:526–535.

Cegala DJ, McClure L, Marinelli TM, et al. The effects of communication skills training on patients' participation during medical interviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;41:209–222.

Schinkel S, Schouten BC, Street RL Jr, van den Putte B, van Weert JC. Enhancing health communication outcomes among ethnic minority patients: the effects of the match between participation preferences and perceptions and doctor-patient concordance. Health Commun. 2016;21:1251–1259.